We continue our tour of current assets with the firm’s accounts receivable. When one company sells goods to another, it does not usually expect to be paid immediately. These unpaid bills, or trade credit, compose the bulk of accounts receivable. The remainder is made up of consumer credit, that is, bills that are awaiting payment by the final customer.

Management of trade credit requires answers to five sets of questions:

- How long are you going to give customers to pay their bills? Are you prepared to offer a cash discount for prompt payment?

- Do you require some formal IOU from the buyer or do you just ask him or her to sign a receipt?

- How do you determine which customers are likely to pay their bills?

- How much credit are you prepared to extend to each customer? Do you play it safe by turning down any doubtful prospects? Or do you accept the risk of a few bad debts as part of the cost of building a large regular clientele?

- How do you collect the money when it becomes due? What do you do about reluctant payers or deadbeats?

We discuss each of these topics in turn.

1. Terms of Sale

Not all sales involve credit. For example, if you are supplying goods to a wide variety of irregular customers, you may demand cash on delivery (COD). And, if your product is custom-designed, it may be sensible to ask for cash before delivery (CBD) or to ask for progress payments as the work is carried out.

When we look at transactions that do involve credit, we find that each industry seems to have its own particular practices.4 These norms have a rough logic. For example, firms selling consumer durables may allow the buyer a month to pay, while those selling perishable goods, such as cheese or fresh fruit, typically demand payment in a week. Similarly, a seller may allow more extended payment if its customers are in a low-risk business, if their accounts are large, if they need time to check the quality of the goods, or if the goods are not quickly resold.

To encourage customers to pay before the final date, it is common to offer a cash discount for prompt settlement. For example, pharmaceutical companies commonly require payment within 30 days but may offer a 2% discount to customers who pay within 10 days. These terms are referred to as “2/10, net 30.”

If goods are bought on a recurrent basis, it may be inconvenient to require separate payment for each delivery. A common solution is to pretend that all sales during the month in fact occur at the end of the month (EOM). Thus goods may be sold on terms of 8/10 EOM, net 60. This arrangement allows the customer a cash discount of 8% if the bill is paid within 10 days of the end of the month; otherwise the full payment is due within 60 days of the invoice date.

Cash discounts are often very large. For example, a customer who buys on terms of 2/10, net 30 may decide to forgo the cash discount and pay on the thirtieth day. This means that the customer obtains an extra 20 days’ credit but pays about 2% more for the goods. This is equivalent to borrowing money at a rate of 44.6% per annum.5 Of course, any firm that delays payment beyond the due date gains a cheaper loan but damages its reputation.

2. The Promise to Pay

Repetitive sales to domestic customers are almost always made on open account. The only evidence of the customer’s debt is the record in the seller’s books and a receipt signed by the buyer.

If you want a clear commitment from the buyer before you deliver the goods, you can arrange a commercial draft.6 This works as follows: You draw a draft ordering payment by the customer and send this to the customer’s bank together with the shipping documents. If immediate payment is required, the draft is termed a sight draft; otherwise it is known as a time draft. Depending on whether it is a sight draft or a time draft, the customer either pays up or acknowledges the debt by signing it and adding the word accepted. The bank then hands the shipping documents to the customer and forwards the money or trade acceptance to you, the seller.

If your customer’s credit is shaky, you can ask the customer to arrange for a bank to accept the time draft and thereby guarantee the customer’s debt. These bankers’ acceptances are often used in overseas trade. The bank guarantee makes the debt easily marketable. If you don’t want to wait for your money, you can sell the acceptance to a bank or to another firm that has surplus cash to invest.

3. Credit Analysis

There are a number of ways to find out whether customers are likely to pay their debts. For existing customers an obvious indication is whether they have paid promptly in the past. For new customers you can use the firm’s financial statements to make your own assessment, or you may be able to look at how highly investors value the firm.[4] However, the simplest way to assess a customer’s credit standing is to seek the views of a specialist in credit assessment. For example, in Chapter 23, we described how bond rating agencies, such as Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s, provide a useful guide to the riskiness of the firm’s bonds.

Bond ratings are usually available only for relatively large firms. However, you can obtain information on many smaller companies from a credit agency. Dun and Bradstreet is by far the largest of these agencies and its database contains credit information on millions of businesses worldwide. Credit bureaus are another source of data on a customer’s credit standing. In addition to providing data on small businesses, they can also provide an overall credit score for individuals.[5]

Finally, firms can also ask their bank to undertake a credit check. It will contact the customer’s bank and ask for information on the customer’s average balance, access to bank credit, and general reputation.

Of course you don’t want to subject each order to the same credit analysis. It makes sense to concentrate your attention on the large and doubtful orders.

4. The Credit Decision

Let us suppose that you have taken the first three steps toward an effective credit operation. In other words, you have fixed your terms of sale; you have decided on the contract that customers must sign; and you have established a procedure for estimating the probability that they will pay up. Your next step is to work out which of your customers should be offered credit.

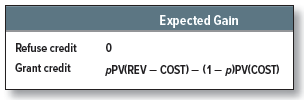

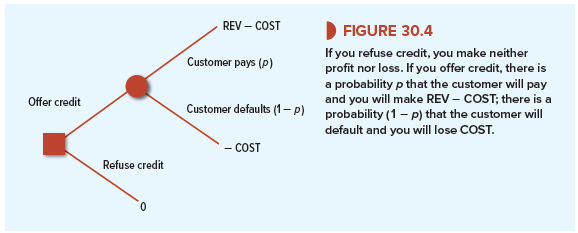

If there is no possibility of repeat orders, the decision is relatively simple. Figure 30.4 summarizes your choice. On one hand, you can refuse credit. In this case, you make neither profit nor loss. The alternative is to offer credit. Suppose that the probability that the customer will pay up is p. If the customer does pay, you receive additional revenues (REV) and you incur additional costs; your net gain is the present value of REV – COST. Unfortunately, you can’t be certain that the customer will pay; there is a probability (1 – p) of default. Default means that you receive nothing and incur the additional costs. The expected profit from each course of action is therefore as follows:

You should grant credit if the expected gain from doing so is positive.

Consider, for example, the case of the Cast Iron Company. On each nondelinquent sale Cast Iron receives revenues with a present value of $1,200 and incurs costs with a value of $1,000. Therefore the company’s expected profit if it offers credit is

![]()

If the probability of collection is 5/6, Cast Iron can expect to break even:

![]()

Therefore Cast Iron’s policy should be to grant credit whenever the chances of collection are better than 5 out of 6.

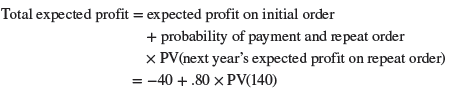

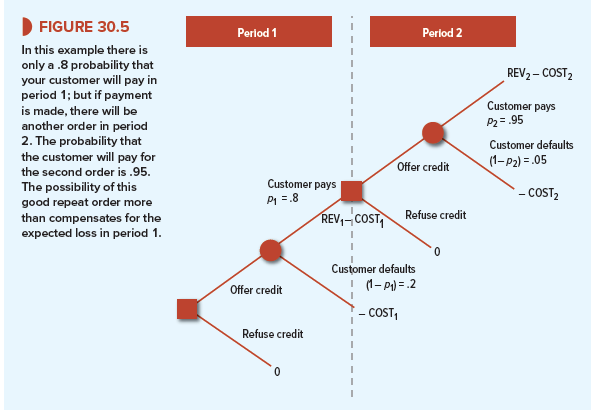

So far, we have ignored the possibility of repeat orders. But one of the reasons for offering credit today is that it may help to get yourself a good, regular customer. Figure 30.5 illustrates the problem. Cast Iron has been asked to extend credit to a new customer. You can find little information on the firm, and you believe that the probability of payment is no better than .8. If you grant credit, the expected profit on this customer’s order is

![]()

You decide to refuse credit.

This is the correct decision if there is no chance of a repeat order. But look again at the decision tree in Figure 30.5. If the customer does pay up, there will be a repeat order next year. Because the customer has paid once, you can be 95% sure that he or she will pay again. For this reason any repeat order is very profitable:

![]()

Now you can reexamine today’s credit decision. If you grant credit today, you receive the expected profit on the initial order plus the possible opportunity to extend credit next year:

At any reasonable discount rate, you ought to extend credit. Notice that you should do so even though you expect to take a loss on the initial order. The expected loss is more than outweighed by the possibility that you will secure a reliable and regular customer. Cast Iron is not committed to making further sales to the customer, but by extending credit today, it gains a valuable option to do so. It will exercise this option only if the customer demonstrates its creditworthiness by paying promptly.

Of course real-life situations are generally far more complex than our simple Cast Iron examples. Customers are not all good or all bad. Many of them pay consistently late; you get your money, but it costs more to collect and you lose a few months’ interest. Then there is the uncertainty about repeat sales. There may be a good chance that the customer will give you further business, but you can’t be sure of that and you don’t know for how long she will continue to buy.

Like almost all financial decisions, credit allocation involves a strong dose of judgment. Our examples are intended as reminders of the issues involved rather than as cookbook formulas. Here are the basic things to remember.

- Maximize profit. As credit manager, you should not focus on minimizing the number of bad accounts; your job is to maximize expected profit. You must face up to the following facts: The best that can happen is that the customer pays promptly; the worst is default. In the best case, the firm receives the full additional revenues from the sale less the additional costs; in the worst, it receives nothing and loses the costs. You must weigh the chances of these alternative outcomes. If the margin of profit is high, you are justified in a more liberal credit policy; if it is low, you cannot afford many bad debts.[6]

- Concentrate on the dangerous accounts. You should not expend the same effort on analyzing all credit applications. If an application is small or clear-cut, your decision should be largely routine; if it is large or doubtful, you may do better to move straight to a detailed credit appraisal. Most credit managers don’t make decisions on an order-byorder basis. Instead, they set a credit limit for each customer. The sales representative is required to refer the order for approval only if the customer exceeds this limit.

- Look beyond the immediate order. The credit decision is a dynamic problem. You cannot look only at the present. Sometimes it may be worth accepting a relatively poor risk as long as there is a good chance that the customer will become a regular and reliable buyer. New businesses must, therefore, be prepared to incur more bad debts than established businesses. This is part of the cost of building a good customer list.

5. Collection Policy

The final step in credit management is to collect payment. When a customer is in arrears, the usual procedure is to send a statement of account and to follow this at intervals with increasingly insistent letters or telephone calls. If none of these has any effect, most companies turn the debt over to a collection agent or an attorney.

Large firms can reap economies of scale in record keeping, billing, and so on, but the small firm may not be able to support a fully fledged credit operation. However, the small firm may be able to obtain some scale economies by farming out part of the job to a factor.

Factoring typically works as follows. The factor and the client agree on a credit limit for each customer. The client then notifies the customer that the factor has purchased the debt. Thereafter, whenever the client makes a sale to an approved customer, it sends a copy of the invoice to the factor, and the customer makes payment directly to the factor. Most commonly the factor does not have any recourse to the client if the customer fails to pay, but sometimes the client assumes the risk of bad debts. There are, of course, costs to factoring, and the factor typically charges a fee of 1% or 2% for administration and a roughly similar sum for assuming the risk of nonpayment. In addition to taking over the task of debt collection, most factoring agreements also provide financing for receivables. In these cases, the factor pays the client 70% to 80% of the value of the invoice in advance at an agreed interest rate. Of course, factoring is not the only way to finance receivables; firms can also raise money by borrowing against their receivables.

Factoring is common in Europe, but in the United States it accounts for only a small proportion of debt collection. It is most common in industries such as clothing and toys. These industries are characterized by many small producers and retailers that do not have long-term relationships. Because a factor may be employed by a number of manufacturers, it sees a larger proportion of the transactions than any single firm, and therefore is better placed to judge the creditworthiness of each customer.

There is always a potential conflict of interest between the collection operation and the sales department. Sales representatives commonly complain that they no sooner win new customers than the collection department frightens them off with threatening letters. The collection manager, on the other hand, bemoans the fact that the sales force is concerned only with winning orders and does not care whether the goods are subsequently paid for.

There are also many instances of cooperation between the sales force and the collection department. For example, the specialty chemical division of a major pharmaceutical company actually made a business loan to an important customer that had been suddenly cut off by its bank. The pharmaceutical company bet that it knew its customer better than the customer’s bank did. The bet paid off. The customer arranged alternative bank financing, paid back the pharmaceutical company, and became an even more loyal customer. It was a nice example of financial management supporting sales.

It is not common for suppliers to make business loans in this way, but they lend money indirectly whenever they allow a delay in payment. Trade credit can be an important source of funds for indigent customers that cannot obtain a bank loan. But that raises an important question: If the bank is unwilling to lend, does it make sense for you, the supplier, to continue to extend trade credit? Here are two possible reasons why it may make sense: First, as in the case of our pharmaceutical company, you may have more information than the bank about the customer’s business. Second, you need to look beyond the immediate transaction and recognize that your firm may stand to lose some profitable future sales if the customer goes out of business.

I went over this website and I believe you have a lot of good info , saved to my bookmarks (:.