In the previous chapter it was noted that the primary roles of the PM were to manage trade-offs and manage risks. In addition to managing trade-offs and risks, the PM also has several other important roles including serving as a facilitator, communicator, virtual project manager, and convener and chair of meetings.

1. Facilitator

First, to understand the PM’s roles, it is useful to compare the PM with a functional manager. The head of a function such as manufacturing or marketing directs the activities of a well-established unit or department of the firm. Presumably trained or raised from the ranks, the functional manager has expertise in the technology being managed. He is an accountant, or an industrial engineer, or a marketing researcher, or a shop foreman, or so on. The functional manager’s role, therefore, is mainly that of supervisor (literally “overseer”). Because the project’s place in the parent organization is often not well defined and does not seem to fit neatly in any one functional division, neither is the PM’s place neatly defined. Because projects are often multidisciplinary, the PM rarely has technical competence in more than one or two of the several technologies involved in the project. As a result, the PM is not a competent overseer and thus has a different role. The PM is a facilitator.

Facilitator versus Supervisor The PM must ensure that those who work on the project have the appropriate knowledge and resources, including that most precious resource, time, to accomplish their assigned responsibilities. The work of a facilitator does not stop with these tasks. For reasons that will be apparent later in this chapter, the project is often beset with conflict—conflict between members of the project team, conflict between the team and senior managers (particularly managers of the functional divisions), conflict with the client and other outsiders. The PM must manage these conflicts by negotiating resolution of them.

Actually, the once sharp distinction between the manager-as-facilitator and the manager-as-supervisor has been softened in recent years. With the slow but steady adoption of the participative management philosophy, the general manager has become more and more like the project manager. In particular, responsibility for the planning and organization of specific tasks is given to the individuals or groups that must perform them, always constrained, of course, by company policy, legality, and conformity to high ethical standards. The manager’s responsibility is to make sure that the required resources are available and that the task is properly concluded. The transition from traditional authoritarian management to facilitation continues because facilitation is more effective as a managerial style.

A second important distinction between the PM and the traditional manager is that the former uses the systems approach and the latter adopts the analytical approach to understanding and solving problems. The analytical approach centers on understanding the bits and pieces in a system. It prompts study of the molecules, then atoms, then electrons, and so forth. The systems approach includes study of the bits and pieces, but also an understanding of how they fit together, how they interact, and how they affect and are affected by their environment. The traditionalist manages his or her group (a subsystem of the organization) with a desire to optimize the group’s performance. The systems approach manager conducts the group so that it contributes to total system optimization. It has been well demonstrated that if all subsystems are optimized, a condition known as suboptimization, the total system is not even close to optimum performance. (Perhaps the ultimate example of suboptimization is “The operation was a success, but the patient died.”) We take this opportunity to recommend to you an outstanding book on business, The Goal, by Goldratt and Cox (1992). It is an easy-to-read novel and a forceful statement on the power of the systems approach as well as the dangers of suboptimization.

Systems Approach To be successful, the PM must adopt the systems approach. Consider that the project is a system composed of tasks (subsystems) which are, in turn, composed of subtasks, and so on. The system, a project, exists as a subsystem of the larger system, a program, that is a subsystem in the larger system, a firm, which is . . . and so on. Just as the project’s objectives influence the nature of the tasks and the tasks influence the nature of the subtasks, so does the program and, above it, the organization influence the nature of the project. To be effective, the PM must understand these influences and their impacts on the project and its deliverables.

Think for a moment about designing a new airplane—a massive product development project—without knowing a great deal about its power plant, its instrumentation, its electronics, its fuel subsystems—or about the plane’s desired mission, the intended takeoff and landing facilities, the intended carrying capacity, and intended range. One cannot even start the design process without a clear understanding of the subsystems that might be a part of the plane and the larger systems of which it will be a part as well as those that comprise its environment.

Given a project and a deliverable with specifications that result from its intended use in a larger system within a known or assumed environment, the PM’s job is straightforward. Find out what tasks must be accomplished to produce the deliverable. Find out what resources are required and how those resources may be obtained. Find out what personnel are needed to carry out production and where they may be obtained.

Find out when the deliverable must be completed. In other words, the PM is responsible for planning, organizing, staffing, budgeting, directing, and controlling the project; the PM “manages” it. But others, the functional managers for example, will staff the project by selecting the people who will be assigned to work on the project. The functional managers also may develop the technical aspects of the project’s design and dictate the technology used to produce it. The logic and illogic of this arrangement will be revisited later in this chapter.

Micromanagement At times, the PM may work for a program manager who closely supervises and second-guesses every decision the PM makes. Such bosses are also quite willing to help by instructing the PM exactly what to do. This unfortunate condition is known as micromanagement and is one of the deadly managerial sins. The PM’s boss rationalizes this overcontrol with such statements as “Don’t forget, I’m responsible for this project,” “This project is very important to the firm,” or “I have to keep my eye on everything that goes on around here.” Such statements deny the value of delegation and assume that everyone except the boss is incompetent. This overweening self-importance practically ensures mediocre performance, if not outright project failure. Any project successes will be claimed by the boss. Failures will be blamed on the subordinate PM.

There is little a PM can do about the “My way or the highway” boss except to polish the resume or request a transfer. (It is a poor career choice to work for a boss who will not allow you to succeed.) As we will see later in this chapter, the most successful project teams tend to adopt a collegial style. Intrateam conflict is minimized or used to enhance team creativity, cooperation is the norm, and the likelihood of success is high.

2. Communicator

The PM must be a person who can handle responsibility. The PM is responsible to the project team, to senior management, to the client, and to anyone else who may have a stake in the project’s performance or outcomes. Consider, if you will, the Central Arizona Project (CAP). This public utility moves water from the Colorado River to Phoenix, several other Arizona municipalities, and to some American Indian reservations. The water is transported by a system of aqueducts, reservoirs, pipes, and pumping stations. Besides the routine delivery of water, almost everything done at CAP is a project. Most of the projects are devoted to the construction, repair, and maintenance of their system. Now consider a PM’s responsibilities. A maintenance team, for instance, needs resources in a timely fashion so that maintenance can be carried out according to a precise schedule. The PM’s clients are municipalities. The drinking public (water, of course) is a highly interested stakeholder. The system is even subject to partisan political turmoil because CAP-supplied water is used as a political football in Tucson.

The PM is in the middle of this muddle of responsibility and must manage the project in the face of all these often-conflicting interests. CAP administration, the project teams, the municipalities (and their Native American counterparts), and the public all communicate with each other—often contentiously. In general, we often call this the “context” of the project. More accurately, given the systems approach we have adopted, this is the environment of the project.

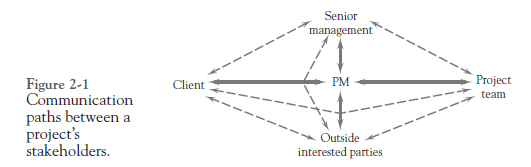

Figure 2-1 shows the PM’s position and highlights the communication problem involved in any project. The solid lines denote the PM’s communication channels. The dotted lines denote communication paths for the other stakeholders in the project. Problems arise when some of these parties propagate communications that may mislead other parties, or directly conflict with other messages in the system. It is the PM’s responsibility to introduce some order into this communication mess.

For example, assume that senior management calls for tighter cost control or even for a cost reduction. The project team may react emotionally with a complaint that “They want us to cut back on project quality!” The PM must intervene to calm ruffled team feathers and, perhaps, ask a senior manager to reassure the project team that high quality is an organizational objective though not every gear, cog, and cam needs to be gold-plated.

Similarly, the client may drop in to check on a project and blithely ask a team member, “Would it be possible to alter the specs to include such-and-such?” The team member may think for a moment about the technical problems involved and then answer quite honestly, “Yeah, that could be done.” Again, the PM must intervene—if and when the question and answer come to light—to determine the cost of making such a change, as well as the added time that would be required. The PM must then ask whether the client wishes to alter the project scope given the added cost and delayed delivery. This scenario is so common it has a name, scope creep. It is the PM’s nightmare.

To compound these issues further, conventional thinking suggests different stakeholders (e.g., clients, the parent organization, the project team, and the public) define success and failure in different ways. For example, the client wants changes and the parent organization wants profits. Likewise, the individuals working on projects are often responsible to two bosses at the same time—a functional manager and the project manager (discussed in more detail later in this chapter). Under such conditions conflict can arise when the two bosses have different priorities and objectives.

While the conventional view tends to regard conflict as a rather ubiquitous part of working on projects, more recently, others have challenged this view. For example, John Mackey, cofounder and co-CEO of Whole Foods Market, suggests in his recent book Conscious Capitalism (2013) that satisfying stakeholder needs is not a zero-sum game where satisfying one stakeholder must come at the expense of another. Rather, Mackey suggests a better approach is to identify opportunities to satisfy all stakeholder needs simultaneously. One way to accomplish this is to identify ways to align the goals of all stakeholders with the purpose of the project. As was mentioned earlier, one of the primary roles of the project manager is to manage the trade-offs. However, as Mackey warns, if we look for trade-offs, we will always find trade-offs. On the other hand, if we look for synergies across the stakeholder base, we can often find them too. The clear lesson for project managers is to not be too quick to assume only trade-offs exist among competing project objectives and stakeholder groups.

Identifying and Analyzing Stakeholders We concur with Mackey that the preferred approach is to proactively take steps to align the goals of the various stakeholders with the purpose of the project. To facilitate this, several techniques for identifying and analyzing stakeholders are discussed in this section.

Before the goals of the shareholders can be aligned with the purpose of the project, the stakeholders must be identified. Most commonly, the expert judgment of the PM and project team are employed to identify the stakeholders. After identifying the stakeholders,

a stakeholder register should be created to maintain key information about them including contact information, their requirements and expectations, what stage in the project they have the most interest in, their power over the project, and so on. In addition, separate from the stakeholder register, a stakeholder issue log should be maintained to catalog issues that arise and how they were resolved.

Once the stakeholders have been identified, a number of tools can be used to analyze them to gain insight about how to manage the relationship with them. And as additional information is learned about a stakeholder, the stakeholder register should be updated.

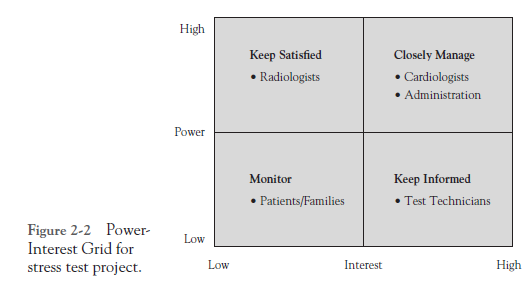

For the purpose of illustrating a couple of representative stakeholder analysis tools, we will use the example of a process improvement project that is about to be launched at a hospital with the goal of reducing the turnaround times for patients’ stress tests. The turnaround time for a stress test is measured as the elapsed time from when the stress test was ordered by a cardiologist until the results are signed off by a radiologist. Delays in receiving the results from stress tests impact the timeliness of treating patients which in turn impacts the patients’ length of stay at the hospital. For the purpose of this example, we further assume that during an early project team meeting, the PM and process improvement team identified the following stakeholder groups: radiologists, cardiologists, hospital administration, the stress test technicians, and the patients/families.

One tool that is useful for analyzing stakeholders is the Power-Interest Grid. As its name suggests, this tool analyzes stakeholders on two dimensions: their interest in the project and their relative power in the organization. Based on these two dimensions the model suggests the appropriate relationship between the PM and the stakeholder group from monitoring to keeping informed, to keeping satisfied, to closely managing. Figure 2-2 provides an illustrative Power-Interest Grid for the stress test process improvement project.

Referring to Figure 2-2, we observe that the PM should closely manage the cardiologists and hospital administrators, given their high interest in the project and their power in the organization. Likewise, the radiologists (who are in effect the customers of this project) should be kept satisfied. Finally, the patients/families should be monitored and the test technicians kept informed on the status of the project.

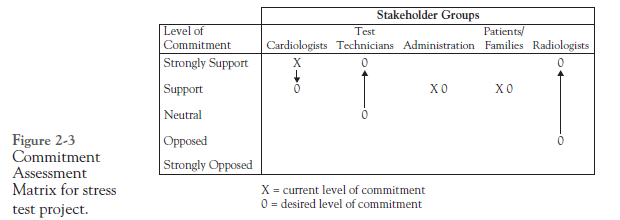

In addition to thoughtfully considering the type of relationship the PM and project team should have with stakeholders, it is also important to assess how much engagement and commitment is needed from various stakeholder groups in order for the project to succeed. A useful tool for accessing the level of commitment needed from stakeholders is the Commitment Assessment Matrix. In this matrix, both the current level of commitment and the desired level of commitment are assessed for each stakeholder group.

Figure 2-3 provides an example Commitment Assessment Matrix for the stress test process improvement project. In comparing the current and desired levels of commitment to the process improvement project, we observe that the cardiologists are more committed than desired perhaps indicating the risk that they will interfere in unproductive ways with the project. On the other hand, for the project to succeed, greater commitment is needed from the test technicians and especially the radiologists. Thus, the PM and project team need to develop an appropriate communication plan to reduce the cardiologists’ commitment to the project and to substantially increase the commitment of the test technicians and radiologists.

Managing stakeholder engagement is an important process and because of this was added as a new knowledge area in the most recent update to the PMBOK. According to Section 13.3 in the PMBOK, managing stakeholder engagement involves the following activities:

- Obtaining and confirming stakeholders’ commitment to the project’s success at the appropriate stages in the project.

- Communicating with stakeholders to manage their expectations.

- Proactively addressing stakeholder concerns before they become major issues.

- Resolving issues in a timely fashion once they have been identified.

3. Virtual Project Manager

More and more often, project teams are geographically dispersed. Many projects are international, and team members may be on different continents, for example, aircraft engine design and engine construction. Many are carried out by different organizations in different locations. For example, Boeing created global supplier/strategic partner teams for their 787 Dreamliner aircraft to co-design and produce various portions of the new plane: the vertical fin in Seattle, WA, the cockpit in Wichita, KS, the wings in Japan, and the center fuselage in Italy. Similarly, many projects involve different divisions of one firm where the divisions are in different cities. These geographically dispersed projects are often referred to as “virtual projects,” possibly because so much of the intraproject communication is conducted via email, through websites, by telephone or video conferencing, and other high-technology methods. In recent decades, the international dispersion of industry, “globalization,” has dramatically increased the communication problems, adding the need for translators to the virtual communication networks. An interesting view of “virtual” people who work in one country but live in another (often on another continent) is given in a Wall Street Journal article (Flynn, 1999).

Long-distance communication is commonplace and no longer prohibitively expensive. It may, however, be beset with special problems. In the case of written and voice-only communication (and even in video conferencing when the camera is not correctly aimed), the communicators cannot see one another. In such cases we realize how much we depend on feedback—the facial expression and body language that let us know if our messages are received and with what level of acceptance. Two-way, real-time communication is the most effective way to transmit information or instructions. For virtual projects to succeed, communication between PM and project team must be frequent, open, and two-way.

The PM’s responsibility for communication with senior management poses special problems for any PM without fairly high levels of self-confidence. Formal and routine progress reports aside (cf. Chapter 7), it is the PM’s job to keep senior management up to date on the state of the project. It is particularly important that the PM keep management informed of any problems affecting the project—or any problem likely to affect the project in the future. A golden rule for anyone is “Never let the boss be surprised!” Violations of this rule will cost the PM credibility, trust, and possibly his or her job. Where there is no trust, effective communication ceases. Senior management must be informed about a problem in order to assist in its solution. The timing of this information should be at the earliest point a problem seems likely to occur. Any later is too late. This builds trust between the PM and senior managers. The PM who is trusted by the project sponsor and can count on assistance when organizational clout is needed is twice blessed.

The PM is also responsible to the client. Clients are motivated to stay in close touch with a project they have commissioned. Because they support the project, they feel they have a right to intercede with suggestions (requests, alterations, demands). Cost, schedule, and scope changes are the most common outcome of client intercession, and the costs of these changes often exceed the client’s expectations. Note that it is not the PM’s job to dissuade the client from changes in the project’s scope, but the PM must be certain that the client understands the impact of the changes on the project’s goals of delivery time, cost, and scope.

The PM is responsible to the project team just as team members are responsible to the PM. As we will see shortly, it is very common for project team members to be assigned to work on the project, but to report to a superior who is not connected with the project. Thus, the PM will have people working on the project who are not “direct reports.” Nonetheless, the relationship between the team and the PM may be closer to boss- subordinate than one might suspect. The reason for this is that both PM and team members often develop a mutual commitment to the project and to its successful conclusion. The PM facilitates the work of the team, and helps them succeed. As we will see in the final chapter, the PM may also take an active interest in fostering team members’ future careers. Like any good boss, the PM may serve as advisor, counselor, confessor, and interested friend.

4. Meetings, Convener and Chair

The two areas in which the PM communicates most frequently are reports to senior management and instructions to the project team. We discuss management reports in Chapter 7 on monitoring and controlling the project. We also set out some rules for conducting successful meetings in Chapter 7. Communication with the project team typically takes place in the form of project team meetings. When humorist Dave Barry reached 50, he wrote a column listing 25 things he had learned in his first 50 years of living. Sixteenth on the list is “If you had to identify, in one word, the reason why the human race has not and never will achieve its full potential, that word would be ‘meetings’.”

Most of the causes of meeting-dread are associated with failure to adopt common sense about when to call meetings and how to run them. As we have said, one of the first things the PM must do is to call a “launch meeting” (see Chapter 3). Make sure that the meeting starts on time and has a prearranged stopping time. As convener of the meeting, the PM is responsible for taking minutes and keeping the meeting on track. The PM should also make sure that the invitation to the meeting includes a written agenda that clearly explains the purpose for the meeting and includes sufficient information on the project to allow the invitees to come prepared—and they are expected to do so. For some rules on conducting effective meetings that do not result in angry colleagues, see the subsection on meetings in Chapter 7.

The PM is a facilitator, unlike the traditional manager who is a supervisor. The PM must adopt the systems approach to making decisions and managing projects. Trying to optimize each part of a project, suboptimization, does not produce an optimized project. Multiple communication paths exist in any project, and some paths bypass the PM, causing problems. Much project communication takes place in meetings that may be run effectively if some simple rules are followed. In virtual projects, much communication is via high technology channels. Above all, the PM must keep senior management informed about the current state of the project.

Source: Meredith Jack R., Mantel Jr. Samuel J., Shafer Scott M., Sutton Margaret M. (2017), Project Management in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3th Edition.

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021