Announcements of dividends and repurchases can convey information about management’s confidence and so affect the stock price. But eventually, the stock price change would happen anyway as information seeps out through other channels. Does payout policy affect value in the long run?

Suppose you are CFO of a successful, profitable public company. The company is maturing. Growth is slowing down, and you plan to distribute free cash flow to stockholders. Does it matter whether you initiate dividends or a repurchase program? Does the choice affect the market value of your firm in any fundamental way?

One of the endearing features of economics is its ability to accommodate not just two, but three opposing points of view. And so it is with the choice between dividends and repurchases. On the right are conservatives who argue that investors pay more for firms with generous, stable dividends. On the left, another group argues that repurchases are better because dividends are taxed at higher effective rates than capital gains. And in the center, a middle-of-the-road party claims that the choice between dividends and repurchases has no effect on value.

1. Payout Policy Is Irrelevant in Perfect Capital Markets

The middle-of-the-road party was founded in 1961 by Miller and Modigliani (always referred to as “MM”), when they published a proof that dividend policy is value-irrelevant in a world without taxes, transaction costs, and other market imperfections.12

MM insisted that one must consider dividend policy only after holding the firm’s assets, investments, and borrowing policy fixed. Suppose they were not fixed. For example, suppose that the firm decides to reduce capital investment and to pay out the cash saved as a dividend. In this case, the effect of the dividend on shareholder value is tangled up with the profitability of the foregone investment. Or suppose that the firm decides to borrow more aggressively and to pay out the debt proceeds as dividends. In this case, the effect of the dividend can’t be separated from the effect of the additional borrowing.

Think what happens if you want to up the dividend without changing the investment policy or capital structure. The extra cash for the dividend must come from somewhere. If the firm fixes its borrowing, the only way it can finance the extra dividend is to sell more shares. Alternatively, rather than increasing dividends and selling new shares, the firm can pay lower dividends. With investment policy and borrowing fixed, the cash that is saved can only be used to buy back some of the firm’s existing shares. Thus any change in dividend payout must be offset by the sale or repurchase of shares.

Repurchases were rare when MM wrote in 1961, but we can easily apply their reasoning to the choice between dividends and repurchases. A simple example is enough to show MM’s irrelevance result in this case. Then we will show that value is also unaffected if the company increases the dividend and finances the increase with an issue of shares.

2. Dividends or Repurchases? An Example

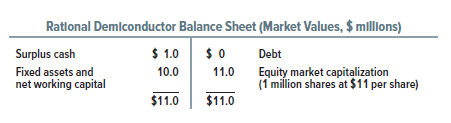

Rational Demiconductor has, at this moment, 1 million shares outstanding and the following market-value balance sheet:

For simplicity we assume it has no debt. All of its fixed assets are paid for. Its working capital includes enough cash to support its operations, so the $1 million cash entered at the top left of its balance sheet is surplus.

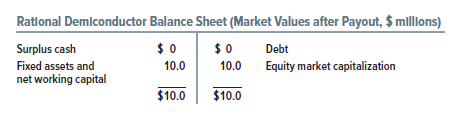

Rational’s market capitalization is $11 million, so each of its 1 million shares is worth $11. If it now pays out the surplus cash, market capitalization must fall to $10 million:

But the price per share depends on whether the surplus cash is paid out as a dividend or by repurchases. If a dividend of $1 per share is paid, 1 million shares are still outstanding, and stock price is $10. Shareholders’ wealth, including the cash dividends, is $10 + 1 = $11 per share.

Suppose Rational pays no cash dividend, but repurchases shares instead. It spends $1 million to repurchase 90,909 shares at $11 each, leaving 909,091 shares outstanding. Stock price remains at $11 ($10 million divided by 909,091 shares). Shareholders’ wealth is $11 per share. It doesn’t matter whether a particular shareholder decides to sell shares back to the firm. If she sells, she gets $11 per share in cash. If she doesn’t want to sell, she retains shares worth $11 each.

Thus, shareholder wealth is the same with dividends as with repurchases. If Rational pays a cash dividend, wealth is $10 + 1 = $11, including the dividend. If Rational repurchases, there is no dividend, but each share is worth $11.

You may hear a claim that share repurchases should increase the stock price. That’s not quite right, as our example illustrates. A repurchase does not increase the stock price, but it avoids the fall in stock price that would occur on the ex-dividend day if the amount spent on repurchases were paid out as cash dividends. Repurchases do not guarantee a higher stock price, but only a stock price higher than if a dividend were paid instead. Repurchases also reduce the number of shares outstanding, so future earnings per share are higher than if the same amount were paid out as dividends.

If MM and the middle-of-the-roaders are correct and payout policy does not affect value, then the choice between dividends and repurchases is merely tactical. A company will decide to repurchase if it wants to retain the flexibility to cut back payout if valuable investment opportunities arise. Another company may decide to pay dividends to assure stockholders that it will run a tight ship, paying out free cash flow to limit the temptation for careless spending.

3. Stock Repurchases and DCF Models of Share Price

Our example looked at a one-time choice between a cash dividend and repurchase program. In practice, a company that pays a dividend today also makes an implicit promise to continue paying dividends in later years, smoothing the dividends and increasing them gradually as earnings grow. Repurchases are not smoothed in the same way as dividends. For example, when oil prices tumbled in 2014, Chevron announced that it was scrapping its stock repurchase program for 2015. The company compared repurchases to a “flywheel” that can store or disperse energy as needed. At the same time that it cut its repurchases, the company stressed that maintaining its current dividend remained “the highest priority.”

A repurchase program reduces the number of outstanding shares and increases earnings and dividends per share. Thus we should pause and consider what repurchases imply for the DCF dividend-discount models that we derived and applied in Chapter 4. These models say that stock price equals the PV of future dividends per share. How do we apply these models when the number of shares is changing?

There are two valuation approaches for common stocks when repurchases are important:

- Calculate market capitalization (the aggregate value of all shares) by forecasting and discounting all the free cash flow paid out to shareholders. Then calculate price per share by dividing market capitalization by the number of shares currently outstanding. With this approach, you don’t have to worry about how payout of free cash flow is split between dividends and repurchases.

- Calculate the present value of dividends per share, taking account of the increased growth rate of dividends per share caused by the declining number of shares resulting from the repurchases.

The first valuation approach, which focuses on the total free cash flow available for payout to shareholders, is easier and more reliable when future repurchases are erratic or unpredictable.

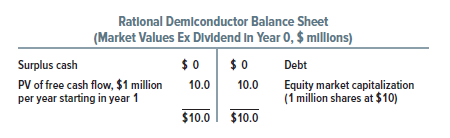

We illustrate by continuing the Rational Demiconductor example. Suppose that Rational has just paid a cash dividend of $1 per share, reducing ex-dividend market capitalization to $10 million. We now reveal the source of Rational’s equity value. Its operations are expected to generate a level, perpetual stream of earnings and free cash flow (FCF) of $1 million per year (no forecasted growth or decline). The cost of capital is r = .10, or 10%. Thus, the market capitalization of all of Rational’s currently outstanding shares is PV = FCF/r = 1/.10 = $10 million.

The price per share equals market capitalization divided by the shares currently outstanding: $10 million divided by 1 million = $10 per share. This is the first valuation approach.

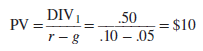

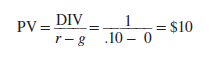

The second approach requires an assumption about future payout policy. Life is easy if Rational commits to dividends only, no repurchases. In that case, the forecasted dividend stream is level and perpetual at $1 per share. We can use the constant-growth DCF model with a growth rate g = 0. Share price is

But suppose that Rational announces instead that henceforth it will pay out exactly 50% of earnings as dividends and 50% as repurchases. (We assume that stockholders who sell their stock back to the company do not miss out on the dividend.) This means that next year’s dividend will be only $.50. On the other hand, Rational will use $500,000 (50% of earnings) to buy back shares. It will repurchase 47,619 shares at the ex-dividend price of $10.50 per share, and shares outstanding will fall to 1,000,000 – 47,619 = 952,381 shares.[1] Thus expected earnings per share for year 2 increase to $1 million divided by 952,381 = $1.05 per share. So the $.50 reduction in the dividend for year 1 has been offset by 5% growth in future earnings per share, from $1 to $1.05 in year 2. And if you carry this example forward to year 3 and beyond, you will see that using 50% of earnings for repurchases continues to generate a growth rate in earnings and dividends per share of 5% per year.

So the DCF model comes back to exactly the same value for Rational’s shares today, just as MM would predict. The repurchase program decreases next year’s dividend from $1.00 to $.50 per share but generates 5% growth in earnings and dividends per share.

Thus, we can get to Rational’s price per share in two ways. The easy first method is to calculate equity market capitalization based on total free cash flow and then divide by the current number of shares outstanding. The second, more difficult method is to forecast and discount dividends per share, taking account of the growth in dividends per share caused by repurchases. We recommend the easy way when repurchases are important. Note also that the second way, which works out nicely in our example, becomes much more difficult to do precisely when repurchases are irregular or unpredictable.

Our example illustrates several general points. First, absent tax effects or other market frictions, today’s market capitalization and share price are not affected by how future payout is split between dividends and repurchases. Second, shifting payout to repurchases reduces current dividends but produces an offsetting increase in future earnings and dividends per share. Third, when valuing cash flow per share, it is double-counting to include both the forecasted dividends per share and cash received from repurchases. If you sell back your share, you don’t get any subsequent dividends.

4. Dividends and Share Issues

We have considered dividend policy as the choice between cash dividends or repurchases. If we hold total payout constant, smaller dividends mean larger repurchases. But, as we noted earlier, MM derived their dividend-irrelevance theorem when repurchases were rare. So MM asked whether a corporation could increase value by paying larger cash dividends. But they still insisted on holding investment and debt-financing policy fixed.

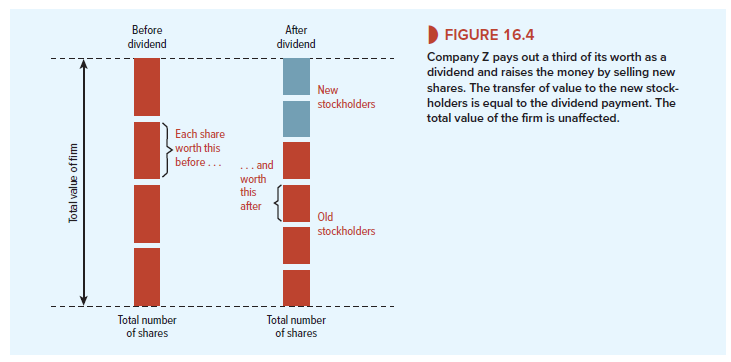

Suppose a company like Rational Demiconductor has paid out any surplus cash. Now it wants to impress investors by paying out an even larger dividend. The extra money must come from somewhere. If the firm fixes its borrowing, the only way it can finance the extra dividend is to print some more shares and sell them. The new stockholders are going to part with their money only if you can offer them shares that are worth as much as they cost. But how can the firm sell more shares when its assets, earnings, investment opportunities, and, therefore, market value are all unchanged? The answer is that there must be a transfer of value from the old to the new stockholders. The new ones get the newly printed shares, each one worth less than before the extra dividend was announced, and the old ones suffer a capital loss on their shares. The capital loss borne by the old shareholders just offsets the extra cash dividend they receive.

Turn back to the first Rational Demiconductor balance sheet, which shows the company starting with $1 million of surplus cash, $1 per share. Suppose it decides to pay an annual dividend of $2 per share. To do so it will have to issue new shares (sooner or later) to replace the extra $1 million of cash that just went out the door. The ex-dividend stock price is $9, so it will have to issue 111,111 shares to raise $1 million. The issue brings Rational’s equity market capitalization back to 1,111,111 X $9 = $10 million. Thus, Rational’s shareholders receive a dividend of $2 versus $1 per share, but the extra cash in their pockets is exactly offset by a lower stock price. They own a smaller fraction of the firm, because Rational had to finance the extra dividend by issuing 111,111 new shares.[2]

Figure 16.4 shows how this transfer of value occurs. Assume that Company Z pays out a third of its total value as a dividend and it raises the money to do so by selling new shares. The capital loss suffered by the old stockholders is represented by the reduction in the size of the red boxes. But that capital loss is exactly offset by the fact that the new money raised (the blue boxes) is paid over to them as dividends. The firm that sells shares to pay higher dividends is simply recycling cash. To suggest that this makes shareholders better off is like advising the cook to cool the kitchen by leaving the refrigerator door open.

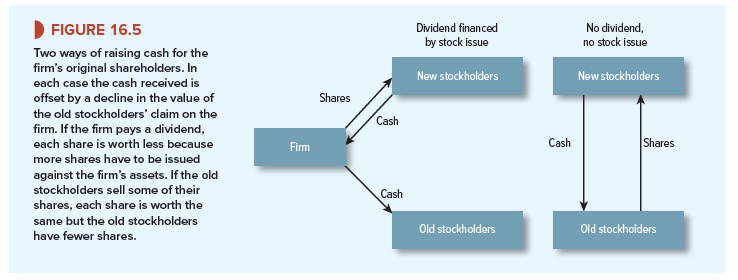

Does it make any difference to the old stockholders that they receive an extra dividend payment plus an offsetting capital loss? It might if that were the only way they could get their hands on cash. But as long as there are efficient capital markets, they can raise the cash by selling shares. Thus, the old shareholders can cash in either by persuading the management to pay a higher dividend or by selling some of their shares. In either case there will be a transfer of value from old to new shareholders. The only difference is that in the former case, this transfer is caused by a dilution in the value of each of the firm’s shares, and in the latter case, it is caused by a reduction in the number of shares held by the old shareholders. The two alternatives are compared in Figure 16.5.

Because investors do not need dividends to get their hands on cash, they will not pay higher prices for the shares of firms with high payouts. Therefore, firms should not worry about paying low dividends or no dividends at all.

Of course, this conclusion ignores taxes, issue costs, and a variety of other complications. We turn to these in a moment. The really crucial assumption in our proof is that the new shares are sold at a fair price. The shares that the company sells for $1 million must be worth $1 million. In other words, we have assumed efficient markets.

We’re a gaggle of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community. Your web site provided us with useful info to work on. You’ve performed an impressive job and our whole community might be grateful to you.