We first addressed problems of valuation and capital budgeting in Chapters 5 and 6. In those early chapters, we said hardly a word about financing decisions. We separated investment from financing decisions. If the investment project was positive-NPV, we assumed that the firm would go ahead, without asking whether financing the project would add or subtract additional value. We were really assuming a Modigliani-Miller (MM) world in which all financing decisions are irrelevant. In a strict MM world, firms can analyze real investments as if they are all-equity-financed; the actual financing plan is a mere detail to be worked out later.

Under MM assumptions, decisions to spend money can be separated from decisions to raise money. Now we reconsider the capital budgeting decision when investment and financing decisions interact and cannot be wholly separated.

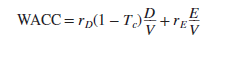

One reason financing and investment decisions interact is taxes. Interest is a tax-deductible expense. Think back to Chapters 9 and 17, where we introduced the after-tax weighted- average cost of capital:

![]()

Here D and E are the market values of the firm’s debt and equity, V = D + E is the total market value of the firm, rD and rE are the costs of debt and equity, respectively, and Tc is the marginal corporate tax rate.

Notice that the WACC formula uses the after-tax cost of debt rD(1 – Tc). That is how the after-tax WACC captures the value of interest tax shields. Notice too that all the variables in the WACC formula refer to the firm as a whole. As a result, the formula gives the right discount rate only for projects that are just like the firm undertaking them. The formula works for the “average” project. It is incorrect for projects that are safer or riskier than the average of the firm’s existing assets. It is incorrect for projects whose acceptance would lead to an increase or decrease in the firm’s target debt ratio.

The WACC is based on the firm’s current characteristics, but managers use it to discount future cash flows. That’s fine as long as the firm’s business risk and debt ratio are expected to remain constant, but when the business risk and debt ratio are expected to change, discounting cash flows by the WACC is just approximately correct.

Many firms set a single, companywide WACC and update it only if there are major changes in risk and interest rates. The WACC is a common reference point that avoids divisional squabbles about discount rates.1 But all financial managers need to know how to adjust WACC when business risks and financing assumptions change. We show how to make these adjustments later in this chapter.

EXAMPLE 19.1 ● Calculating Sangria’s WACC

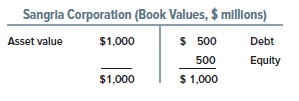

Sangria is a U.S.-based company whose products aim to promote happy, low-stress lifestyles. Let’s calculate Sangria’s WACC. Its book and market-value balance sheets are

We calculated the market value of equity on Sangria’s balance sheet by multiplying its current stock price ($7.50) by 100 million, the number of its outstanding shares. The company’s future prospects are good, so the stock is trading above book value ($7.50 vs. $5.00 per share). However, interest rates have been stable since the firm’s debt was issued, so the book and market values of debt are, in this case, equal.

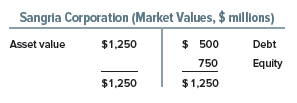

Sangria’s cost of debt (the market interest rate on its existing debt and on any new borrowing)[1] [2] is 6%. Its cost of equity (the expected rate of return demanded by investors in Sangria’s stock) is 12.5%.

The market-value balance sheet shows assets worth $1,250 million. Of course, we can’t observe this value directly because the assets themselves are not traded. But we know what they are worth to debt and equity investors ($500 + 750 = $1,250 million). This value is entered on the left of the market-value balance sheet.

Why did we show the book balance sheet? Only so you could draw a big X through it. Do so now.

Think of the WACC as the expected rate of return on a portfolio of the firm’s outstanding debt and equity. The portfolio weights depend on market values. The expected rate of return on the market-value portfolio reveals the expected rate of return demanded by investors for committing their hard-earned money to the firm’s assets and operations.

When estimating the weighted-average cost of capital, you are not interested in past investments but in current values and expectations for the future. Sangria’s true debt ratio is not 50%, the book ratio, but 40% because its assets are worth $1,250 million. The cost of equity, rE = .125, is the expected rate of return from purchase of stock at $7.50 per share, the current market price. It is not the return on book value per share. You can’t buy shares in Sangria for $5 anymore.

Sangria is consistently profitable and pays taxes at the marginal rate of 21%.[3] This tax rate is the final input for Sangria’s WACC. The inputs are summarized here:

The company’s after-tax WACC is

WACC = .06 x (1 – .21) x .4 + .125 x .6 = .094, or 9.4%

EXAMPLE 19.2 ● Using Sangria’s WACC to Value a Project

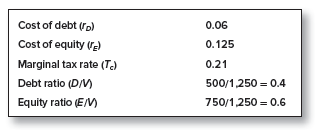

Sangria’s enologists have proposed investing $12.5 million in the construction of a perpetual crushing machine, which (conveniently for us) never depreciates and generates a perpetual stream of earnings and cash flow of $1.487 million per year pretax. The project is average risk, so we can use WACC. The after-tax cash flow is:

Note: This after-tax cash flow takes no account of interest tax shields on debt supported by the perpetual crusher project. As we explained in Chapter 6, standard capital budgeting practice separates investment from financing decisions and calculates after-tax cash flows as if the project were all-equity-financed. However, the interest tax shields will not be ignored: We are about to discount the project’s cash flows by Sangria’s WACC, in which the cost of debt is entered after tax. The value of interest tax shields is picked up not as higher after-tax cash flows, but in a lower discount rate.

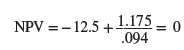

The crusher generates a perpetual after-tax cash flow of C = $1.175 million, so NPV is

NPV = 0 means a barely acceptable investment. The annual cash flow of $1.175 million per year amounts to a 9.4% rate of return on investment (1.175/12.5 = .094), exactly equal to Sangria’s WACC.

If project NPV is exactly zero, the return to equity investors must exactly equal the cost of equity, 12.5%. Let’s confirm that Sangria shareholders can actually look forward to a 12.5% return on their investment in the perpetual crusher project.

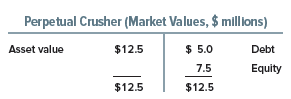

Suppose Sangria sets up this project as a mini-firm. Its market-value balance sheet looks like this:

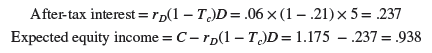

Calculate the expected dollar return to shareholders:

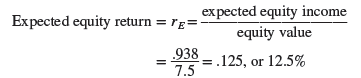

The project’s earnings are level and perpetual, so the expected rate of return on equity is equal to the expected equity income divided by the equity value:

The expected return on equity equals the cost of equity, so it makes sense that the project’s NPV is zero.

1. Review of Assumptions

It is appropriate to discount the perpetual crusher’s cash flows at Sangria’s WACC only if

- The project’s business risks are the same as those of Sangria’s other assets and remain so for the life of the project.

- Throughout its life, the project supports the same fraction of debt to value as in Sangria’s overall capital structure.

You can see the importance of these two assumptions: If the perpetual crusher had greater business risk than Sangria’s other assets, or if the acceptance of the project would lead to a permanent, material change in Sangria’s debt ratio, then Sangria’s shareholders would not be content with a 12.5% expected return on their equity investment in the project.

But users of WACC need not worry about small or temporary fluctuations in debt ratios. Nor should they be misled by the immediate source of financing. Suppose that Sangria decides to borrow $12.5 million to get a quick start on construction of the crusher. This does not necessarily change Sangria’s long-term financing targets. The crusher’s debt capacity is only $5 million. If Sangria decides for convenience to borrow $12.5 million for the crusher, then sooner or later it will have to borrow $12.5 – $5 = $7.5 million less for other projects.

We have illustrated the WACC formula only for a project offering perpetual cash flows. But the formula works for any cash-flow pattern as long as the firm adjusts its borrowing to maintain a constant debt ratio over time.[4] When the firm departs from this borrowing policy, WACC is only approximately correct.

2. Mistakes People Make in Using the Weighted-Average Formula

The weighted-average formula is very useful, but it is also dangerous. It tempts people to make logical errors. For example, manager Q, who is campaigning for a pet project, might look at the formula

and think, “Aha! My firm has a good credit rating. It could borrow, say, 90% of the project’s cost if it likes. That means D/V = .9 and E/V = .1. My firm’s borrowing rate rD is 8%, and the required return on equity, rE, is 15%. The tax rate is now 21%. Therefore,

WACC = .08(1 – .21)(.9) + .15(.1) = .072

or 7.2%. When I discount at that rate, my project looks great.”

Manager Q is wrong on several counts. First, the weighted-average formula works only for projects that are carbon copies of the firm. The firm isn’t 90% debt-financed.

Second, the immediate source of funds for a project has no necessary connection with the hurdle rate for the project. What matters is the project’s overall contribution to the firm’s borrowing power. A dollar invested in Q’s pet project will not increase the firm’s debt capacity by $.90. If the firm borrows 90% of the project’s cost, it is really borrowing in part against its existing assets. Any advantage from financing the new project with more debt than normal should be attributed to the old projects, not to the new one.

Third, even if the firm were willing and able to lever up to 90% debt, its cost of capital would not decline to 7.2%, as Q’s naive calculation predicts. You cannot increase the debt ratio without creating financial risk for stockholders and thereby increasing rE, the expected rate of return they demand from the firm’s common stock. Going to 90% debt would certainly increase the borrowing rate, too.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to your blog when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?