The aim of situation analysis is to understand the current and future environment in which the company operates in order that the strategic objectives are realistic in light of what is happening in the marketplace. Figure 8.5 shows the inputs from situation analysis that inform the e-marketing plan. These mainly refer to a company’s external environment.

The study of an organization’s online environment was introduced in Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.3 where it was noted that there was the immediate (micro-)environment of customers, competitors, suppliers and intermediaries and a broader (macro-)environment of social, legal, political, economic and technological characteristics. Situation analysis will involve consideration of all of these factors and will form the basis for defining objectives, strategies and tactics. Consideration of the SLEPT or macro-environment factors is a major topic that is covered in Chapter 4. In this chapter we will concentrate on what needs to be analysed about the more immediate marketplace in terms of customers, competitors, intermediaries and market structure. An internal audit of the capability of the resources of the company such as its people, processes and technology also needs to take place.

In Chapter 5 we introduced the use of a SWOT analysis for an organizations’ digital channels. The SWOT can be used to summarize the range of analyses covered in this section. Figure 8.6 gives an example of a typical Internet SWOT.

1. Demand analysis

A key factor driving e-marketing and e-business strategy objectives is the current level and future projections of customer demand for e-commerce services in different market segments (see Strategic analysis, Chapter 5, p. 269). This will influence the demand for products online and this, in turn, should govern the resources devoted to different online channels. Demand analysis examines current and projected customer use of each digital channel and different services within different target markets. It can be determined by asking for each market:

- What percentage of customer businesses have access to the Internet?

- What percentage of members of the buying unit in these businesses have access to the Internet?

- What percentage of customers are prepared to purchase your particular product online?

- What percentage of customers with access to the Internet are not prepared to purchase online, but are influenced by web-based information to buy products offline?

- What is the popularity of different online customer engagement devices such as Web 2.0 features such as blogs, online communities and RSS feeds?

- What are the barriers to adoption amongst customers of different channels and how can we encourage adoption?

Savvy e-marketers use tools provided by search engine services such as Google to evaluate the demand for their products or services based on the volume of different search terms typed in by search engine users Table 8.1 shows the volume of searches for these generic, broad keywords. The numbers in the table are huge in any country, but most users also narrow their searches using phrases like ‘free online banking, ‘cuba holidays’ and ‘ski jackets’. This enables online suppliers to target their messages to consumers looking for these products in the search engines through advertising services such as Google and Overture (Yahoo! Search Marketing).

Through evaluating the volume of phrases used to search for products in a given market it is possible to calculate the total potential opportunity and the current share of search terms for a company. ‘Share of search’ can be determined from web analytics reports from the company site which indicate the precise key phrases used by visitors to actually reach a site from different search engines.

Thus the situation analysis as part of e-marketing planning must determine levels of access to the Internet in the marketplace and propensity to be influenced by the Internet to buy either offline or online. In a marketing context, the propensity to buy is an aspect of buyer behaviour (The online buying process, Chapter 9).

Figure 8.7 summarizes the type of picture the e-marketing planner needs to build up. For each geographic market the company intends to serve research needs to establish:

- Percentage of customers with Internet (or mobile) access.

- Percentage of customers who access the web site (and different types of services).

- Percentage of customers who will be favourably influenced.

- Percentage of customers who buy online.

Now refer to Activity 8.1 where this analysis is performed for the car market. This picture will vary according to different target markets, so the analysis will need to be performed for each of these. For example, customers wishing to buy ‘luxury cars’ may have web access and a higher propensity to buy than those for small cars.

Qualitative customer research

It is important that customer analysis not be restricted to quantitative demand analysis. Variani and Vaturi (2000) point out that qualitative research provides insights that can be used to inform strategy. They suggest using graphic profiling, which is an attempt to capture the core characteristics of target customers, not only demographics, but also their needs and attitudes and how comfortable they are with the Internet. In Chapter 11 we will review how customer personas and scenarios are developed to help inform understanding of online buyer behaviour.

A summary of the categories of different sources of customer insight that an organization can tap into and their applications is shown in Table 8.2. The challenge within organizations seems to be selecting which paid-for and free services to select and then ensure sufficient time is spent reviewing and actioning the data to create value-adding insights. My experience shows that often data are only used by the digital team and not utilized more widely since in large organizations, staff are unaware of the existence of the data or service provider supplying it. There is also the significant issue of privacy; organizations need to be transparent about how they collect and use these data and give customers choice as discussed in Chapter 4.

As well as external sources, many online businesses are now harnessing customer viewpoints or innovation through their own programmes. Well-known examples from business and consumer fields include:

- Dell Ideastorm (ideastorm.com)

- MyStarbucks Idea (http://mystarbucksidea.com)

- BBC Backstage (http://backstage.bbc.co.uk)

- Lego MindStorm (http://mindstorms.lego.com/community/default.aspx)

- Oracle Mix (https://mix.oracle.com/listens).

You can see how web-savvy companies use the web for marketing research, as a listening channel. They use the web and e-mail channels as means of soliciting feedback and suggestions which contribute to shaping future services.

2. Competitor analysis

Competitor analysis or the monitoring of competitor use of e-commerce to acquire and retain customers is especially important in the e-marketplace due to the dynamic nature of the Internet medium. This enables new services to be launched and promotions changed much more rapidly than through print communications. The implications of this dynamism are that competitor benchmarking is not a one-off activity while developing a strategy, but needs to be continuous.

Benchmarking of competitors’ online services and strategy is a key part of planning activity and should also occur on an ongoing basis in order to respond to new marketing approaches such as price or promotions. According to Chaffey et al. (2009), competitor benchmarking has different perspectives which serve different purposes:

- Review of internal capabilities: such as resourcing, structure and processes vs external customer facing features of the sites.

- From core proposition through branding to online value proposition (OVP). The core proposition will be based on the range of products offered, price and promotion. The OVP describes the type of web services offered which add to a brand’s value.

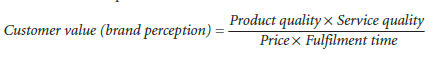

Deise et al. (2000) suggested an ‘equation’ that can be used to appraise competitors from their customers’ viewpoint:

- Different aspects of the customer lifecycle: customer acquisition, conversion to retention. Competitor capabilities should be benchmarked for all the digital marketing activities of each competitor as shown in Figure 8.1. These should be assessed from the viewpoint of different customer segments or personas, possibly through usability sessions. Performance in search engines using the tools mentioned in Chapter 2 should be reviewed as a key aspect of customer acquisition and brand strength. In addition to usability, customer views should be sought on different aspects of the marketing mix such as pricing and promotions mentioned later in the chapter.

- Qualitative to quantitative: from qualitative assessments by customers through surveys and focus groups through to quantitative analysis by independent auditors of data across customer acquisition (e.g. number of site visitors or reach within market, cost of acquisition, number of customers, sales volumes and revenues and market share); conversion (average conversion rates) and retention such as repeat conversion and number of active customers.

- In-sector and out-of-sector, benchmarking against similar sites within sector and reviewing out of sector to sectors which tend to be more advanced, e.g. online publishers, social networks and brand sites. Benchmarking services are available for this type of comparison from analysts such as Bowen Craggs & Co (bowencraggs.com). An example of one of their benchmark reports is shown in Figure 8.8. You can see that this is based on the expert evaluation of the suitability of the site for different audiences as well as measures under the overall construction (which includes usability and accessibility), message (which covers key brand messages and suitability for international audiences) and contact (which shows integration between different audiences). The methodology states: ‘it is not a “tick box”: every metric is judged by its existence, its quality and its utility to the client, rather than “Is it there or is it not?’’’

- Financial to non-financial measures. Through reviewing competitive intelligence sources such as company reports or tax submissions additional information may be available on turnover and profit generated by digital channels. But other forward-looking aspects of the company’s capability which are incorporated on the balanced scorecard measurement framework (see Chapter 4) should also be considered, including resourcing, innovation and learning.

Deise et al. (2000) also suggest an ‘equation’ that can be used to suggest the overall level of competition when benchmarking:

‘Agility’ refers to the speed at which a company is able to change strategic direction and respond to new customer demands. ‘Reach’ is the ability to connect to potential and existing customers, or to promote products and generate new business in new markets. ‘Time-to-market’ is the product lifecycle from concept through to revenue generation.

- From user experience to expert evaluation. Benchmarking research should take two alternative perspectives, from actual customer reviews of usability to independent expert evaluations.

Now complete Activity 8.2 to gain an appreciation of how benchmarking competitor e-business services can be approached.

3. Intermediary analysis

Chapter 2 highlighted the importance of web-based intermediaries such as portals in driving traffic to an organization’s web site or influencing visitors while they consume content. Situation analysis will also involve identifying relevant intermediaries for a particular

marketplace. These will be different types of portal such as horizontal and vertical portals which will be assessed for suitability for advertising, PR or partnership. This activity can be used to identify strategic partners or will be performed by a media planner or buyer when executing an online advertising campaign.

For example, an online book retailer needs to assess which comparison or aggregator services such as Kelkoo (www.kelkoo.com) and Shopsmart (www.shopsmart.com) it and its competitors are represented on. Questions which are answered by analysis of intermediaries are do competitors have any special sponsorship arrangements and are micro-sites created with intermediaries? The other main aspect of situation analysis for intermediaries is to consider the way in which the marketplace is operating. To what extent are competitors using disintermediation or reintermediation? How are existing channel arrangements being changed?

4. Internal marketing audit

An internal audit will assess the capability of the resources of the company such as its people, processes and technology to deliver e-marketing compared with its competitors. In Chapter 10 we discuss how teams should be restructured and new resources used to deliver competitive online marketing and customer experience. The internal audit will also review the way in which a current web site or e-commerce services performs. The audit is likely to review the following elements of an e-commerce site, which are described in more detail in Focus on measuring and improving performance of e-business systems in Chapter 12:

- Business effectiveness. This will include the contribution of the site to revenue (see reference to the Online revenue contribution section within the Objective setting of Chapter 5), profitability and any indications of the corporate mission for the site. The costs of producing and updating the site will also be reviewed, i.e. cost-benefit analysis.

- Marketing effectiveness. These measures may include:

- leads;

- sales;

- cost of acquiring new customers

- retention;

- market share;

- brand engagement and loyalty;

- customer service.

These measures will be assessed for each of the different product lines delivered through the web site. The way in which the elements of the marketing mix are utilized will also be reviewed.

- Internet effectiveness. These are specific measures that are used to assess the way in which the web site is used, and the characteristics of the audience. Such measures include specialist measures such as unique visitors and page impressions that are collected through web analytics, and also traditional research techniques such as focus groups and questionnaires to existing customers. From a marketing point of view, the effectiveness of the value proposition of the site for the customer should also be assessed.

Source: Dave Chaffey (2010), E-Business and E-Commerce Management: Strategy, Implementation and Practice, Prentice Hall (4th Edition).

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021