We are living through exciting changes from the days when retailing simply meant visiting a store, shopping from a printed catalog, greeting the Avon lady in one’s home, or buying candy from a vending machine. Who would have thought a generation or so ago that a person would have his or her own personal computer with which to research (“surf’ the Web) a stock, learn about a new product, search for bargains, save a trip to the store, and complain about customer service? These activities are taken for granted today. Let’s look at the Web (or the World Wide Web, as it was initially called) from a retailing perspective, remembering that selling on the Web is a form of direct marketing.

Our discussion begins with defining two terms that may be confusing: The Internet is a global electronic superhighway of computer networks that use a common protocol and that are linked by telecommunications lines and satellites. It acts as a single, cooperative virtual network and is maintained by universities, governments, and businesses. The World Wide Web (Web) is one way to access information on the Internet, whereby people work with easy-to-use Web addresses (sites) and pages. Users see words, charts, pictures, and video, and hear audio—which turn their computers, smartphones, and tablets into interactive multimedia centers. People can easily move from site to site by pointing at the proper spot on the screen and clicking a mouse button, or by touching the screen. Browsing software, such as Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Mozilla Firefox, and Apple Safari—as well search engines such as Google, Bing, and Safari—facilitate “Web surfing.” Both the Internet and the Web convey the same theme: online interactive retailing. Because almost all online retailing is done via the Web, our discussion focuses on these topics: the role of the Web, the scope of Web retailing, characteristics of Web users, factors to consider in planning whether to have a Web site, and examples of Web retailers. Visit our blog (www.bermanevansretail .com) for lots of information on E-retailing.

1. The Role of the Web

From the vantage point of the retailer, the World Wide Web can serve manyone or more roles:

- Project a retail presence and enhance the retailer’s image.

- Generate sales as the major source of revenue for an online retailer or as a complementary source of revenue for a store-based retailer.

- Reach geographically dispersed consumers, including foreign ones.

- Provide information to consumers about products carried, store locations, usage information, answers to common questions, customer loyalty programs, and so on.

- Promote new products and fully explain and demonstrate their features.

- Furnish customer service in the form of E-mail, hotlinks, and other communications.

- Be more “personal” with consumers by letting them point and click on topics they choose.

- Conduct a retail business in a cost-efficient manner.

- Obtain customer feedback and reviews, and encourage “conversations” via social media.

- Foster two-way communication through social media.

- Promote special offers and send coupons to Web customers.

- Indicate employment opportunities.

- Present information to potential investors, potential franchisees, and the media.

The role a retailer assigns to the Web depends on (1) whether its major goal is to communicate interactively with consumers, sell goods and services, or engage in both of these activities; (2) whether it is predominantly a traditional store-based retailer that wants to have a Web presence or a newer firm that wants to derive most or all of its sales from the Web; and (3) the level of resources the retailer wants to commit to site development and maintenance. Worldwide, there are millions of Web sites and 650,000+ retailers that each generate at least $1,000 in annual sales.

2. The Scope of Web Retailing

The potential for online retailing is enormous: As of mid-2016, there were 314 million Web users in North America, 604 million in Europe, 1.6 billion in Asia, 344 million in Latin America/Carib- bean, 330 million in Africa, and 123 million in the Middle East.14 Well over 90 percent of U.S. Web users have made at least one online purchase; and 80 + percent have made at least one online purchase in the last 6 months. A decade ago, U.S. shoppers generated 75 percent of worldwide online sales; the amount is now one-quarter and falling—as online shopping has grown around the globe. Today, Chinese online shoppers spend more than anywhere else.

Forrester, a leading Internet research firm, projects that U.S. shoppers will spend $530.1 billion online by 2020. This represents a 57 percent growth from online sales in 2015.15 The high growth of the Web will not be the death knell of store-based retailing. Instead, it will constitute another choice for shoppers, like other forms of direct marketing. There is much higher sales growth for “clicks-and-mortar” Web retailing (multichannel and omnichannel retailing) than “bricks-and-mortar” stores (single-channel retailing) and “clicks-only” Web firms (single-channel retailing). Many shoppers seek a “seamless omnichannel experience,” which enables them to buy online, and pick it up in a local store.

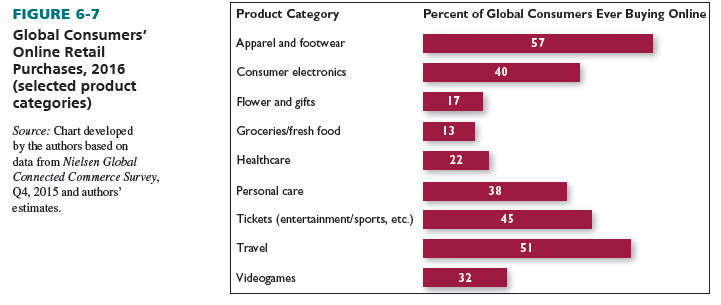

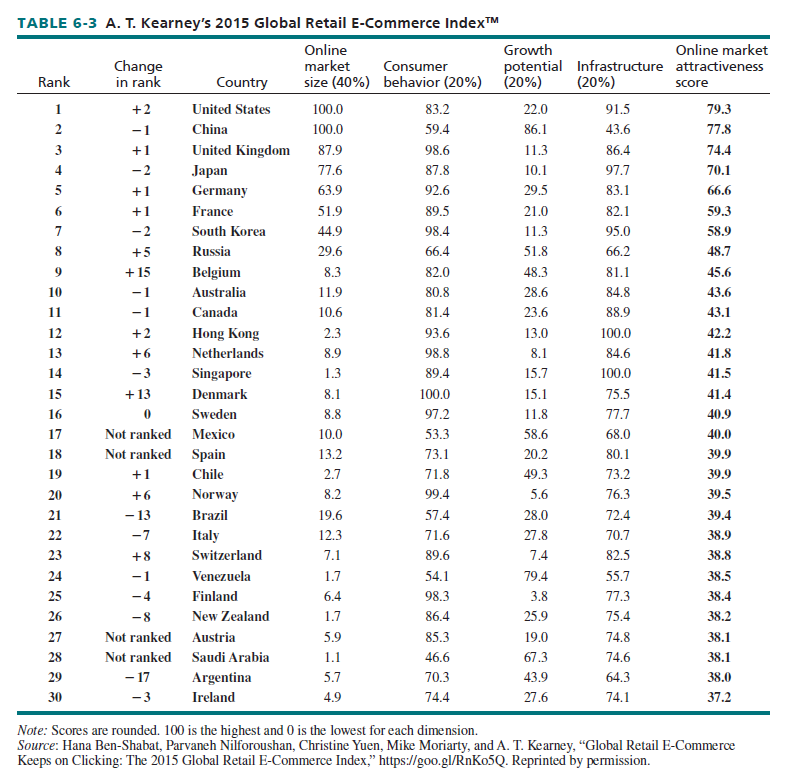

Despite economic challenges worldwide, global online revenues have increased steadily to $2.05 trillion in 2016 and are expected to reach $3.6 trillion in 2019.16 U.S. online retail revenues were $340.61 billion17 and mobile revenues were $89 billion in 2015.18 U.S. retail E-commerce sales as a percent of total retail sales has been increasing since 2006, and has a far higher growth rate than overall retail sales.19 Mobile commerce surged ahead of computer commerce in terms of time spent shopping for the first time in early 2015 (59 percent compared to 41 percent for computer); however, it still lags computers in share of online spending (15 percent to 85 percent).20 Figure 6-7 indicates the percentage of global consumers who have ever made online purchases by selected product category. Table 6-3 shows the most attractive countries in the world for online retailing, as determined by A. T. Kearney’s Global Retail E-Commerce Index.

Despite the foregoing data, the Web accounts for only 8 percent or so of U.S. retail sales! It will not be the death knell of store-based retailing; rather, it will service as another choice for shoppers, like other forms of direct marketing. There is much higher sales growth for “clicks-and- mortar” Web retailing (multichannel and omnichannel retailing) than “bricks-and-mortar” stores (single-channel retailing) and “clicks-only” Web firms (single-channel retailing). Store-based retailers account for more than three-quarters of U.S. online sales.

Consumers may switch between retail formats—online or in-store based on their shopping orientation at each purchase occasion. “Order online, pick up in store” is a very profitable retail option. Retailers need to respond to consumers’ changing habits. British retailer John Lewis used augmented reality to create an “endless showroom” to help its in-store customers browse through thousands of products in all varieties, sizes, colors, and fabrics—available in the store and online—and to get contextual information. This “endless showroom” enables the customers to make a more informed decision and buy faster. The future may mean that less stock is displayed in-store, but it is displayed with more flair as more space is available to create displays that make the consumer go Wow!21

3. Characteristics of Web Users

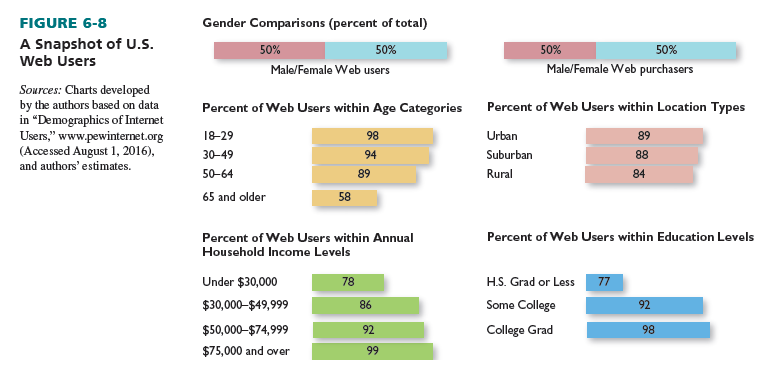

Web users in the United States have these characteristics, which are highlighted in Figure 6-8:

- Gender. There are about as many males as females on the Web; however, females are somewhat more likely to shop online.

- Those who are ages18 to 29 are most likely to use the Web; those who are age 65 and older are least likely.

- Community type.Suburban and urban residents are slightly more apt to use the Web than rural residents.

- Nearly four-fifths of households with an annual income under $30,000 use the Web; in contrast, 99 percent of households with an annual income of at least $75,000 use the Web.

- Those who have attended college are more likely to use the Internet than those who have not, especially those with a high school degree or less.

Following are some key factors for online shoppers regarding their continued patronage. (1) Web site design/interaction: All Web site elements (excluding customer service)—including navigation, information search, product and price offerings, product availability, order processing, and shipment tracking—impact the informational and experiential value customers seek. (2) Reliability: Customers want what they order based on the textual and visual description on the retailer’a Web site and delivery of the right product at the right price (billed correctly, etc.) in good condition within the promised time frame. (3) Service: Customer service expectations include insightful and supportive responses to inquiries and returns/complaints quickly during and after the sale. (4) Privacy/security: Shoppers want to know that their personal data are protected and to be assured that credit-card payments are secure during and after the sale.22

More Web users can be enticed to shop more often if they are assured of privacy, retailers are perceived as trustworthy, sites are easy to maneuver, there are strong money-back guarantees, they can return a product to a store, shipping costs are not hidden until the end of the purchase process, transactions are secure, they can speak with sales representatives, download time is fast, and the retailer has smartphone and tablet apps available.

4. Factors to Consider in Planning Whether to Have a Web Site

The Web offers many advantages for retailers. It is usually less costly to operate a Web site than a store. The potential marketplace is huge and dispersed, yet relatively easy to reach. Web sites can be quite exciting, due to their multimedia capabilities. People can visit Web sites at any time, and their visits can be as short or as long as they desire. Information can be targeted, so that, for example, a person visiting a toy retailer’s Web site could click on the icon labeled “Educational Toys—ages 3 to 6.” A customer database can be established and customer feedback obtained.

The Web also has disadvantages for retailers. For example, if consumers do not know the Web address, it may be hard to find. For various reasons, some people are not yet willing to buy online. There is tremendous clutter with regard to the number of Web sites. Because Web surfers are easily bored, a Web site must be regularly updated to ensure repeat visits. The more multimedia features a Web site has, the slower it may be for people with weak Internet connections to access. Some firms have been overwhelmed with customer service requests and questions from E-mail. It may be hard to coordinate store and Web transactions. There are few standards or rules as to what may be portrayed at Web sites. Consumers expect online services to be free and are reluctant to pay for them.

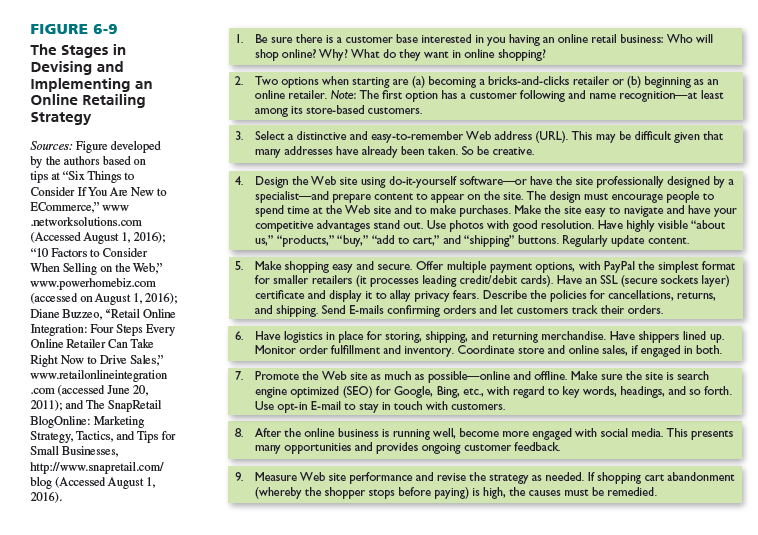

There is a large gulf between full-scale, integrated Web selling and a basic “telling”—rather than “selling”—Web site. A “telling” site emphasizes information about the retailer and where its stores are located; little attention is devoted to facilitating transactions. A “selling” site includes the features of a telling site, but is also a dynamic transaction-oriented approach. Many retailers have responded by simply transferring their existing strategies to an online channel. Instead, they should follow the nine stages highlighted in Figure 6-9.

In addition, to achieve profitable growth in this challenging environment, A. T. Kearney offers “10 Steps to Reach Online Sales Excellence.” These steps show how to shape and implement a strategy to address both the strengths and weaknesses of online retailing in an omnichannel setting. A. T. Kearney clients have seen revenue growth of 40 to 50 percent above the industry average when utilizing this approach:23

- Shape your offering. (1) Define your omnichannel strategy. (2) Shape your assortment to target your customer. (3) Optimize pricing strategies.

- Showcase your assortment.(4) Create interactive and responsive product presentations. (5) Customize the online user experience. (6) Promote your online channel.

- Deliver customer value.(7) Enhance order fulfillment. (8) Boost after-sales services.

- Develop your organization.(9) Analyze your business using big-data methods. (10) Shape your organization.

Web retailers should carefully consider these recommendations, which build on the preceding list. They are compiled from several industry experts:

Develop (or exploit) a well-known, trustworthy retailer name.

- Tailor the product assortment for Web shoppers, and keep freshening the offerings.

- With download speed in mind, provide pictures and ample product information.

- Enable shoppers to make as few clicks as possible to get information and place orders.

- Provide the best possible search engine at the firm’s Web site.

- Capitalize on information about customers and relationships.

- Integrate online and offline businesses, and look for partnering opportunities.

- With permission, save customer data to make future shopping trips easier.

- Indicate shipping fees upfront and be clear about delivery options.

- Do not promote items that are out of stock; and let shoppers know immediately if items will not be shipped for a few days.

- Offer online order tracking.

- Use a secure order entry system for shoppers.

- Prominently state the firm’s return and privacy policies.

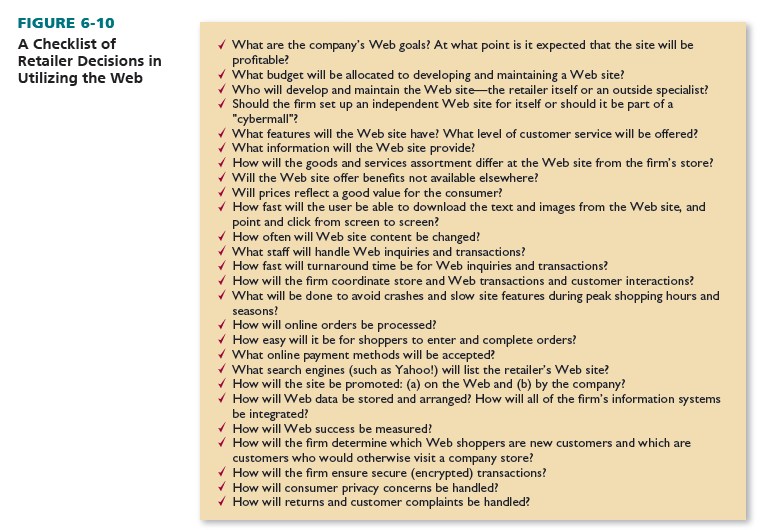

See the checklist in Figure 6-10.

A firm cannot just put up a site and wait for consumers to visit it in droves and then expect them to happily come back. In many cases: (1) It is still difficult for people to find exactly what they are looking for. (2) The inability of the digital interface to convey spatial, haptic (sense of touch), and olfactory cues is a limitation if purchasing products that have experiential attributes. Some large retailers provide virtual online experiences in the form of 3D images and videos— applications that render augmented reality depictions of products; however, this technology is in its early stage of development and needs to be user-friendly. (3) Customer service may be lacking. (4) Friction and barriers between Web sites and their store operations may occur: “Send someone a gift from CompanyA.com and the recipient may be surprised to find it can’t be returned or exchanged at a Company A store.” (5) Privacy policies may not be consumer-oriented. Many online retailers are aggressive in their use of ad-retargeting technology, in which a customer who orders from a Web site, clicks on an E-mail newsletter, fills out a survey, or merely browses the Web site finds his or her E-mail box stuffed with junk mail.24

5. Mobile Apps Enabling Online Retailing

The retail industry has been an early adopter of mobile technology; certainly many retailers have made mobile applications central to their strategies, operations, and customer communications. Almost 30 percent of transactions at U.S. online retailers and travel firms are driven by mobile apps.25 Astute retailers recognize that their mobile app strategy is more than transferring Web site features and functions to the mobile platform; one in five mobile apps are tried once and never opened again.

Any retail mobile app should have the following basic elements: (1) An efficient customer login that provides clear reasons for requiring customers to register, collecting minimal information to personalize customer experiences, and assuring protection of the information. (2) An account management system that allows customers to check and manage their accounts and check rewards information quickly, and that provides links to the mobile site for more complex information requests. (3) Notifications that engage customers and nurture loyalty; 140-character messaging with personalized data, offers, or reward updates serve as reminders to click on the app and connect with the retailer. (4) A “browse products ” service that allows customers to browse products and check inventory online; omnichannel retailers should enable geotargeting so users selecting store pickup automatically default to a local store’s on-hand inventory. (5) A native shopping cart and payment system that allows customers to buy from the mobile app and close the deal, instead of bouncing them to the mobile Web site, which can add delays and increase purchase abandonment. (6) A store locator that gives targeted information about the local store address (connected to a mobile phone mapping app), telephone numbers, and hours.26

6. Examples of Web Retailing in Action

Amazon.com (www.amazon.com) is one of the largest retailers of any type by revenue; it is the largest pure Web retailer in the world, with revenues exceeding $107 billion in 2015, and has tens of millions of customers who buy from the firm each year.27 Amazon.com has three distinct lines: Business Prime, Marketplace, and Amazon Web Services (AWS). They differ in their customer base: AWS serves enterprise customers, Marketplace serves third-party retailers, and Prime serves the best retail customers.

Amazon.com started in 1995 as just an online bookseller. Its core business has greatly evolved. Amazon Prime is subscription-based—a “physical-digital hybrid” including not just free 2-day delivery of over 30 million items in 35 cities around the world but it also offers music, photo storage, the Kindle Owners’ Lending Library, and streaming films and TV shows. For example, Prime Video offers exclusive, original, Emmy-award winning shows. Amazon characterizes Prime Video as “feeding the Prime flywheel.” Amazon customers who watch Prime Video are more likely to convert from a free trial to a paid membership, and more likely to renew their annual subscriptions. In 2015, Amazon initiated Prime Day, when Prime members can buy select products at discounted price. It is also an effective way to increase Prime customer acquisition and retention.

Through the Amazon Marketplace, more than 70,000 third-party sellers offer their products on Amazon (for a listing fee), increasing the assortment variety for Amazon customers and leveraging Amazon’s logistics capability for product delivery. Amazon.com has also produced cutting-edge, popular products—Kindle (E-book readers); Firestick and Fire-TV (streaming video and music from Amazon, Netflix, YouTube, and others); Dash (one-touch product ordering from Amazon; and Echo (a voice-enabled wireless speaker that operates as a home-automation hub).28

At the opposite end of the spectrum from Amazon.com is the specialty business of Seamless .com (www.seamless.com). Seamless offers small and large businesses an organized and costcutting way to order food for delivery and pick up from more than 12,000 restaurants and over 80 cuisine types. It provides interactive tools for the entire process—consolidated ordering and invoicing, the monitoring of food and catering expenses, and expense documentation that clients can use for tax purposes. Seamless is the nation’s largest online and mobile food ordering company with more than one million members. It has made ordering food fast and easy for individual employees and business administrators by featuring interactive menus, ratings and reviews, and new restaurants. Office administrators can set ordering “rules” based on expense account allowances for each employee or department on computers or using their mobile applications on multiple platforms. Seamless serves New York; Washington, D.C.; Boston; Chicago; San Francisco; Los Angeles; Philadelphia; London; and other U.S. cities.29

CarMax (www.carmax.com), as highlighted in Figure 6-11, is a leading bricks-and-clicks retailer that sells new and used cars and buys used cars. It has 150 retail outlets. On the Web site, shoppers can find the cars with the specific features that they want to buy, find out the exact prices of those cars (CarMax has no-haggle pricing), find the location of the nearest dealers, and schedule appointments to see the value of used cars that customers want to sell to Carmax.30

Dollar Tree (www.dollartree.com), as depicted in Figure 6-12, is another bricks-and-clicks retailer with a unique online strategy. It has one of the few sites where customers can shop for items priced at $1—the amount of every Dollar Tree product. On the Web site, customers can find information on Dollar Tree’s Value Seekers Club, access ads and catalogs, read a company blog, shop, and more. Because of its low-price policy, customers can order online and pick up in the store for no delivery fee, but they must pay a delivery fee if they want items shipped to them.

Other interesting Web retailing illustrations include eBay (www.ebay.com), Priceline.com (www.priceline.com), and uBid.com (www.ubid.com), all of which offer online auctions. Even the nonprofit Goodwill has an auction Web site (www.shopgoodwill.com) to sell donated items.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

I’ve been browsing on-line more than 3 hours as of late, but I never discovered any fascinating article like yours. It’s lovely price sufficient for me. In my view, if all web owners and bloggers made excellent content as you did, the net will likely be much more helpful than ever before.