There are three different location types: isolated store, unplanned business district, and planned shopping center. Each has its own attributes as to the composition of competitors, parking, nearness to nonretail institutions (such as office buildings), and other factors. Step 2 in the location process is to determine which type of location to use.

1. The Isolated Store

An isolated store is a freestanding retail outlet located on either a highway or a street. There are no adjacent retailers with which this type of store shares traffic. The advantages of this type of retail location are many:

- There is no competition in close proximity.

- Rental costs are relatively low.

- There is flexibility; no group rules affect operations, and larger space may be obtained.

- Isolation is good for stores involved in one-stop or convenience shopping.

- Better road and traffic visibility is possible.

- Facilities can be adapted to individual specifications.

- Easy parking can be arranged.

- Cost reductions are possible, leading to lower prices.

There are also various disadvantages to this retail location type:

- Initial customers may be difficult to attract.

- Many people will not travel very far to get to one store on a continuous basis.

- Most people like variety in shopping.

- Advertising expenses may be high.

- Costs such as outside lighting, security, grounds maintenance, and trash collection are not shared.

- Other retailers and community zoning laws may restrict access to desirable locations.

- A store must often be built rather than rented.

- As a rule, unplanned business districts and planned shopping centers are much more popular among consumers; they generate most of retail sales.

Large-store formats (such as Walmart supercenters and Costco membership clubs) and convenience-oriented retailers (such as 7-Eleven) are usually the retailers best suited to isolated locations due to the challenge of attracting a target market. A small specialty store would probably be unable to develop a customer following; people would be unwilling to travel to a store that does not have a large assortment of products or a strong image for merchandise and/or prices.

Years ago, numerous shopping centers forbade discounters because discounting was frowned on by anchor retailers. This forced discounters to seek isolated sites or to build their own centers; and they have been successful. Today, diverse retailers are in isolated locales as well as at business district and shopping center sites. Retailers using a mixed-location strategy include McDonald’s, Target, Sears, Starbucks, Toys “R” Us, Walmart, and 7-Eleven. Some retailers, including many gas stations and convenience stores, still emphasize isolated locations. See Figure 10-1.

2. The Unplanned Business District

An unplanned business district is a type of retail location where two or more stores situate together (or in close proximity) in such a way that the total arrangement or mix of stores is not due to prior long-range planning. Stores locate based on what is best for them, not the district. For example, four shoe stores may exist in an area with no pharmacy. There are four kinds of unplanned business districts: central business district, secondary business district, neighborhood business district, and string. A discussion of each follows.

CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT A central business district (CBD) is the hub of retailing in a city. It is synonymous with the term downtown. The CBD exists where there is the greatest density of office buildings and stores. Both vehicular and pedestrian traffic are very high. The core of a CBD is often no more than a square mile, with cultural and entertainment facilities surrounding it. Shoppers are drawn from the whole urban area and include all ethnic groups and all classes of people. The central business district has at least one major department store and a number of specialty and convenience stores. The arrangement of stores follows no pre-set format; it depends on history (first come, first located), retail trends, and luck.

Here are some strengths that allow central business districts to draw a large number of shoppers:

- Excellent goods/service assortment

- Access to public transportation

- Variety of store types and positioning strategies within one area

- Wide range of prices

- Variety of customer services

- High level of pedestrian traffic (see Figure 10-2)

- Nearness to commercial and social facilities

- In addition, chain headquarters stores are often situated in central business districts.

- These are some of the inherent weaknesses of the CBD:

- Inadequate parking, as well as traffic and delivery congestion Travel time for those living in the suburbs

- Frail condition of some cities—such as aging stores—compared with their suburbs

- Relatively poor image of central cities to some potential consumers

- High rents and taxes for the most popular sites

- Movement of some popular downtown stores to suburban shopping centers

- Discontinuity of offerings (such as four shoe stores and no pharmacy)

The central business district remains a major retailing force, although its share of overall sales has fallen over the years, as compared with the planned shopping center. Besides the weaknesses cited, much of the drop-off of business is due to suburbanization. In the first half of the twentieth century, most urban workers lived near their jobs. Gradually, many people moved to suburbs— where they are often served by planned shopping centers.

A number of CBDs are doing well, however, and many others are striving to return to their prior stature. They use such tactics as modernizing storefronts and equipment, forming merchants’ associations, modernizing sidewalks and adding brighter lighting, building vertical malls (with several floors of stores), improving transportation networks, closing streets to vehicular traffic (sometimes with disappointing results), bringing in “razzmatazz” retailers such as Apple stores, and integrating a commercial and residential environment known as mixed-use facilities. The renewed popularity of living in urban areas by Millennials and Baby Boomers creates retail needs that go beyond those of the transient daytime population. Vibrant urban shopping districts with mixed-use properties, access to public transport, and entertainment districts appeal to diverse lifestyles and are a competitive advantage for cities.5

A good example of the value of a revitalized CBD is Philadelphia, where there has been a strong long-term effort under way to make the central city more competitive with suburban shopping centers. Consider these facts about Philadelphia’s central business district: $1.5 billion is being spent in streetscape, facade, and public-area improvements to construct 5.5 million square feet of leasable space. Also, some 27,000 new housing units will be added by 2019, converting vacant office buildings, factories, and empty lots into condos, apartments, and single-family housing. This will result in a transformation of neighborhoods, an increase in population, and revitalized retail development. Empty Nesters and Millennials, who make up 40 percent of Philadelphia’s center city population, work and live in the city; and the average household income has been rising. The influx of such retailers as high-end furniture maker Thos. Moser, Vince, Under Armor, Lululemon, Nordstrom Rack, and Bloomingdale’s Outlet is extending the area to nearby neighborhoods and ancillary corridors. Many successful E-commerce sites, including Warby Parker, Bonobos, and Athleta, are establishing brick-and-mortar stores here.

Boston’s Faneuil Hall is another long-term CBD renovation success. When developer James Rouse took over the site originally called Quincy Market, it had three 150-year-old, block-long former food warehouses that were abandoned for nearly a decade. Rouse used landscaping, fountains, banners, open-air courts, street performers, and colorful graphics to enable Faneuil Hall “America’s First Open Marketplace” to capture a festive spirit. Faneuil Hall now combines shopping, eating, and entertainment. Today, it has 100 shops and Bull Market pushcart vendors, 13 full-service restaurants, 35 food stalls, and regular events and entertainment. It attracts 18 million shoppers and visitors yearly.7

Other major CBD revitalization projects have included Annapolis Town Centre (Maryland), Branson Landing (Missouri), City Center District (Dallas), Harborplace Baltimore, Peabody Place (Memphis), Pioneer Place (Portland, Oregon), Grand Central Terminal (New York City), Tower City Center (Cleveland), and Union Station (Washington, D.C.).

SECONDARY BUSINESS DISTRICT A secondary business district (SBD) is an unplanned shopping area in a city or town that is usually bounded by the intersection of two major streets. Cities— particularly larger ones—often have multiple SBDs, each with at least a junior department store (a branch of a traditional department store or a full-line discount store) and/or some larger specialty stores, besides many smaller stores. This format is now more important because cities have “sprawled” over larger geographic areas.

The kinds of goods and services sold in an SBD mirror those in the CBD. However, a secondary business district has smaller stores, less width and depth of merchandise assortment, and a smaller trading area (consumers will not travel as far), and it sells a higher proportion of convenience-oriented items.

The SBD’s major strengths include a good product selection, access to thoroughfares and public transportation, less crowding and more personal service than in a central business district, and placement nearer to residential areas than a CBD. The SBD’s major weaknesses include the discontinuity of offerings, the sometimes high rent and taxes (but not as high as in a CBD), traffic and delivery congestion, aging facilities, parking difficulties, and fewer chain outlets than in the CBD. These weaknesses have generally not affected the SBD as much as the CBD—and parking problems, travel time, and congestion are less for the SBD.

NEIGHBORHOOD BUSINESS DISTRICT A neighborhood business district (NBD) is an unplanned shopping area that appeals to the convenience shopping and service needs of a single residential area. An NBD contains several small stores, such as a dry cleaner, a stationery store, a barber shop and/or a beauty salon, a liquor store, and a restaurant. The leading retailer tends to be a supermarket or a large drugstore. This type of business district is situated on the major street(s) of its residential area.

A neighborhood business district offers a good location, long store hours, good parking, and a less hectic atmosphere than a central business district or secondary business district. On the other hand, there is a more limited selection of goods and services, and prices tend to be higher because competition is less than in a CBD or SBD.

STRING A string is an unplanned shopping area comprising a group of retail stores, often with similar or compatible product lines, located along a street or highway. There is little extension of shopping onto perpendicular streets. A string may start with an isolated store, success then breeding competitors. Car dealers, antique stores, and apparel retailers often situate in strings.

A string location has many of the advantages of an isolated store site (lower rent, more flexibility, better road visibility and parking, and lower operating costs), along with some disadvantages (less product variety, increased travel for many consumers, higher advertising costs, zoning restrictions, and the need to build premises). Unlike an isolated store, a string store has competition at its location. This draws more people to the area and allows for some sharing of common costs. It also means less control over prices and less loyalty toward each outlet. An individual store’s increased traffic flow, due to being in a string rather than an isolated site, may be greater than the customers lost to competitors. This explains why four gas stations locate on opposing corners.

Figure 10-3 shows a map with various unplanned business districts and isolated locations.

3. The Planned Shopping Center

A planned shopping center consists of a group of architecturally unified commercial establishments on a site that is centrally owned or managed, designed and operated as a unit, based on balanced tenancy, and accompanied by parking facilities. Its location, size, and mix of stores are related to the trading area served. Through balanced tenancy, the stores in a planned shopping center complement each other as to the quality and variety of their product offerings, and the kind and number of stores are linked to overall population needs. To ensure balanced tenancy, management of a planned center usually specifies the proportion of total space for each kind of retailer, limits product lines that can be sold by every store, and stipulates what kinds of firms can acquire unexpired leases. At a well-run center, a coordinated and cooperative long-run retailing strategy is followed by all stores.

The planned shopping center has several positive attributes:

- Well-rounded assortments of goods and services based on long-range planning

- Strong suburban population

- Interest in one-stop, family shopping

- Cooperative planning and sharing of common costs

- Creation of distinctive, but unified, shopping center images

- Maximization of pedestrian traffic for individual stores

- Access to highways and availability of parking for consumers

- More appealing than city shopping for some people

- Generally lower rent and taxes than CBDs (except for enclosed regional malls)

- Generally lower theft rates than CBDs

- Popularity of malls—both open(shopping area off-limits to vehicles) and closed(shopping area off-limits to vehicles and all stores in a temperature-controlled facility)

- Growth of discount malls and other newer types of shopping centers

There are also some limitations associated with the planned shopping center:

- Landlord regulations that reduce each retailer’s flexibility, such as required hours

- Generally higher rent than an isolated store

- Restrictions on the goods/services that can be sold by each store

- A competitive environment within the center

- Required payments for items that may be of little or no value to an individual retailer, such as membership in a merchants’ association

- Too many malls in a number of areas (“the malling of America”)

- Rising consumer boredom with and disinterest in shopping as an activity

- Aging facilities of some older centers

- Domination by large anchor stores

There are 115,000 U.S. shopping centers (including convenience, power, lifestyle, and theme centers, as well as airport retailing); 1,000 centers are enclosed malls. Shopping center revenues exceed $2.4 trillion annually and account for nearly one-half of U.S. retail-store sales (including autos and gasoline). About 12.5 million people work in shopping centers. Eighty-five percent of Americans over age 18 visit some type of shopping center in an average month. Nordstrom, Macy’s, Foot Locker, Gap, Sephora, and Hallmark are among the vast number of chains with a strong presence at shopping centers. Some big retailers have also been involved in shopping-center development. Sears has participated in the construction of dozens of shopping centers, and Publix Supermarkets operates centers with hundreds of small tenants. Each year, numerous new centers of all kinds and sizes are built, and retail space is added to existing centers.8 See Figure 10-4.

To sustain their long-term growth, shopping centers are engaging in these practices:

- Several older centers have been renovated, expanded, and/or repositioned. Cherry Hill Mall in Philadelphia; Hamilton Place Mall in Chattanooga; Kentucky Oaks Mall in Paducah, Kentucky; McCain Mall in Little Rock, Arkansas; Westfield Trumbull Shopping Center in Trumbull, Connecticut; and Yorkdale Shopping Centre Mall in Toronto, Canada, have all been revitalized. Visit our blog (www.bermanevansretail.com) for information on shopping centers.

- Certain derivative types of centers foster consumer interest and enthusiasm. Three of these— megamalls, lifestyle centers, and power centers—are discussed a little later in this chapter.

- Shopping centers are responding to shifting lifestyles. They have made parking easier; added ramps for baby strollers and wheelchairs; and included distinctive retailers such as the Apple Store, Apricot Lane, BCBG Max Azria, Juicy Couture, MaxMara, Michael Kors, Rue 21, and Zumiez. They have also introduced more information booths and center directories.

- The retailer mix has broadened at many centers to attract people wanting one-stop shopping. More centers now include banks, stockbrokers, dentists, doctors, beauty salons, TV repair outlets, and/or car rental offices. Centers may also include “temporary tenants” (retailers that lease space, often in mall aisles or walkways, and sell from booths or moving carts). Tenants benefit from the lower rent and short-term commitment; centers benefit by creating more shopping excitement and diversity. Consumers then discover new vendors in unexpected places.

- Open-air malls are gaining popularity because they are less expensive to build, which means lower rents and common-area costs. Many people also like the outdoor shopping experience. A popular example is the Mall at Partridge Creek, an open-air regional center in Clinton Township, Michigan. It is anchored by Nordstrom, Carson’s, and a 14-screen cinema. The center has 90 stores and restaurants. What gives it a special flair? “Partridge Creek has amenities unique to malls in Michigan, including: Bocce ball courts, free Wi-Fi, pop-jet fountains, a TV court, and a 30-foot fireplace.”9 Free events—including concerts, Wellness Wednesdays, and walking clubs—create community involvement and offer retailers opportunities to engage with shoppers.

- More center developers are striving to build their own brand loyalty. Simon and Westfield are among those that have spent millions of dollars to boost their images by promoting their own names—with the Simon Mall name prominently featured at its shopping centers. Simon (www.simon.com) owns and/or manages 230 properties in North America, Europe, and Asia.10

- Some shopping centers use frequent-shopper programs to retain customers and track spending. Simon Insiders earn VIP parking spots and invitations to private mall events in addition to cash back when they spend more than $1,000 in a month at Simon Property Group malls.

There are three types of planned shopping centers: regional, community, and neighborhood.

Their characteristics are noted in Table 10-1, and they are described next.

REGIONAL SHOPPING CENTER A regional shopping center is a large, planned shopping facility appealing to a geographically dispersed market. It has at least one or two department stores (each with at least 100,000 square feet) and 40 to 125 or more smaller retailers. A regional center offers a very broad and deep assortment of shopping-oriented goods and services intended to enhance the consumer’s visit. The market is 100,000+ people who live or work up to a 30-minute drive away. On average, people travel under 20 minutes. A significant trend among regional shopping centers is to add category killers as anchor tenants to replace closed department stores. General Growth Properties has filled 79 of 83 vacant department store locations with such tenants as H&M, Dick’s Sporting Goods, and Wegman’s Food Markets.12

The regional center is the result of a planned effort to re-create the shopping variety of a central city in suburbia. Some regional centers have become the social, cultural, and vocational focal point of a suburban area. They may be used as a town plaza, a meeting place, a concert hall, and a place for a brisk indoor walk. Despite the declining overall interest in shopping, on a typical visit to a regional shopping center, many people spend an average of an hour or more there.

The first outdoor regional shopping center opened in 1950 in Seattle, anchored by a branch of Bon Marche, then a leading downtown department store. Southdale Center (outside Minneapolis), built in 1956 for Target Corporation (then Dayton Hudson), was the first fully enclosed, climate-controlled mall. Today, there are about 1,250 U.S. regional centers of various kinds, and this format has popped up around the world (where small stores still remain the dominant force) from Australia to Brazil to India to Malaysia.

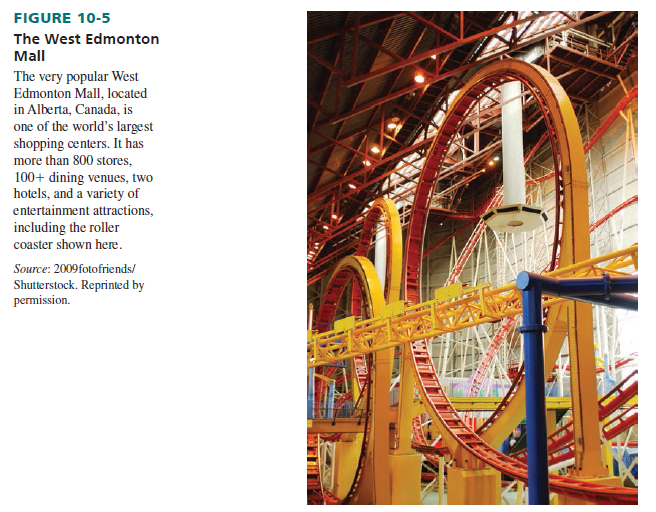

One type of regional center is the megamall, an enormous planned shopping center with 800,000+ square feet of retail space, multiple anchor stores, up to several hundred specialty stores, food courts, entertainment facilities, and a trade area size of up to 25 miles. It seeks to heighten interest in shopping and expand the trading area. There are 625 U.S. megamalls in the United States.13 The largest is the Mall of America (www.mallofamerica.com) in Bloomington, Minnesota. It has three anchors (Macy’s, Nordstrom, and Sears), 520 specialty stores, a 14-screen movie theater, a health club, 50 restaurants, a Nickelodeon Universe indoor amusement park, an aquarium, and 12,550 parking spaces—with 4.2 million square feet of building space. The mall has stores for every budget, attracts between 35 to 40 million visitors yearly (40 percent of visitors are tourists). Beijing, China’s Jinyuan Yansha shopping center (nicknamed the “Great Mall of China”) is the largest megamall in the world. It is 1.5 times the size of Mall of America, with over 1,000 shops and 6 million square feet of space. See Figure 10-5 for another leading megamall.

COMMUNITY SHOPPING CENTER A community shopping center is a moderate-sized, planned shopping facility with a branch department store (traditional or discount) and/or a category killer store, as well as several smaller stores (similar to those in a neighborhood center). It offers a moderate assortment of shopping- and convenience-oriented goods and services to consumers from one or more nearby, well-populated, residential areas. About 20,000 to 100,000 people who live or work within a 10- to 20-minute drive are served by this location. There are 10,000 community shopping centers in the United States.

Better long-range planning occurs for a community shopping center than a neighborhood shopping center. Balanced tenancy is usually enforced, and cooperative promotion is more probable. Store composition and the center’s image are kept pretty consistent with pre-set goals.

Two noteworthy variations of the community center (not included in Table 10-1) are the power center and the lifestyle center. A power center is a shopping site with (1) up to a half-dozen or so category-killer stores and a mix of smaller stores or (2) several complementary stores specializing in one product category. A power center usually occupies 200,000 to 600,000 square feet on a major highway or road intersection. It seeks to be quite distinctive to draw shoppers and better compete with regional centers. There are 2,250 U.S. power centers.14 An example of a power center is 280 Metro Center in Colma, California. The center’s tenants include such category-killer retailers as Marshalls, Nordstrom Rack, Old Navy, David’s Bridal, and Pier 1 Imports.

A lifestyle center is an open-air shopping site that typically includes 150,000 to 500,000 square feet of space dedicated to upscale, well-known specialty stores as well as dining and entertainment. The focus is often on apparel, home products, books, music, and restaurants. Popular stores at lifestyle centers include Ann Taylor, Banana Republic, Bath & Body Works, Gap, Pottery Barn, Talbots, Victoria’s Secret, and Williams-Sonoma. Examples of lifestyle shopping centers include Aspen Grove in Littleton, Colorado; Deer Park Town Center in Illinois; Rookwood Commons in Cincinnati, Ohio; and CocoWalk in Coconut Grove, Florida. At present, there are about 460 such centers in the United States.15

NEIGHBORHOOD SHOPPING CENTER A neighborhood shopping center is a planned shopping facility, with the largest store being a supermarket or a drugstore. Other retailers often include a bakery, laundry, dry cleaner, stationery store, barbershop or beauty parlor, hardware store, restaurant, liquor store, and gas station. This center focuses on convenience-oriented goods and services for people living or working nearby. It serves 3,000 to 50,000 people who are within a 15-minute drive (usually less than 10 minutes). See Figure 10-6.

A neighborhood center is usually arranged in a strip. Initially, it is carefully planned and tenants are balanced. Over time, the planned aspects may lessen and newcomers may face fewer restrictions. Thus, a liquor store might replace a barbershop—leaving a void. A center’s ability to maintain balance depends on its attractiveness to potential tenants (expressed by the extent of store vacancies). In number, but not in selling space or sales, neighborhood centers account for 75 percent of all U.S. regional, community, and other shopping centers.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

You made a few good points there. I did a search on the subject and found most people will agree with your blog.