1. Margins and Spaces

This chapter begins with its title, in full capitals, with left-hand justification (but it could also be centered on the page). The chapter bears a number, in this case an Arabic numeral (below we will see the available alternatives). Then, after three or four blank lines, the title of the section appears flush left, underlined, and preceded by the Arabic numeral of the chapter and that of the section. Then the title of the subsection appears two lines below (or double-spaced). The title of the subsection is not underlined, so as to distinguish it from that of the section. The text begins three lines under this title, and the first word is indented two spaces.

You can decide to indent the text only at the beginning of a section or at the beginning of each paragraph, as we are doing on this page.

The indentation for a new paragraph is important because it shows at a glance that the previous paragraph has ended, and that the argument restarts after a pause. As we have already seen, it is good to begin a new paragraph often, but not randomly. The new paragraph means that a logical period, comprised of various sentences, has organically ended and a new portion of the argument is beginning. It is as if we were to pause while talking to say, “Understood? Agreed?

Good, let us proceed.” Once all have agreed, we begin a new paragraph and proceed, exactly as we are doing in this case.

Once the section is finished, leave three lines between the end of the text and the title of the new section. (This is triple spacing.) Although this chapter is double-spaced, a thesis may be triple-spaced, so that it is more readable, so that it appears to be longer, and so that it is easier to substitute a retyped page. When the thesis is triple-spaced, the distance between the title of a chapter, the title of a section, and any other subhead increases by one line.

If a typist types the thesis, the typist knows how much margin to leave on all four sides of the page. If you type it, consider that the pages will have some sort of binding which will require some space between binding and text, and the pages must remain legible on that side. (It is also a good idea to leave some space on the other side of the page.)

This chapter on formatting, as we have already established, takes the form of typewritten pages of a thesis, insofar as the format of this book allows. Therefore, while this chapter refers to your thesis, it also refers to itself. In this chapter, I underline terms to show you how and when to underline;

I insert notes to show you how to insert notes; and I subdivide chapters, sections, and subsections to show you the criteria by which to subdivide these.

2. Underlining and Capitalizing

The typewriter does not include italic type, only roman type. Therefore, in a thesis you must underline what in a book you would italicize. If the thesis were the typescript for a book, the typographer would then compose in italics all the words you underlined.

What should you then underline? It depends on the type of thesis, but in general, underline the following:

- Foreign words of uncommon use (do not underline those that are already anglicized or currently in use, like the Italian words “ciao” and “paparazzi,” but also “chiaroscuro,” “manifesto,” and “libretto”; in a thesis on particle physics, do not underline words common in that field such as “neutrino”);

- Scientific names such as “felis catus,” “euglena viridis,” “clerus apivorus”;

- Technical terms: “the method of coring in the processes of oil prospecting … “;

- Titles of books (not of book chapters or journal articles);

- Titles of dramatic works, paintings, and sculptures: “In her essay ‘La theorie des mondes possibles dans l’etude des textes: Baudelaire lecteur de Brueghel’ (The theory of possible worlds in the study of texts: Baudelaire as reader of Brueghel), Lucia Vaina-Pusca refers to Hintikka’s Knowledge and Belief in demonstrating that

Baudelaire’s poem ‘The Blind’ is inspired by Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting The Parable of the Blind”;

- Names of newspapers, magazines, and journals: “see the article ‘E dopo le elezioni?’ (What is next after the election?) that appeared in L’Espresso on June 24, 1976”;

- Titles of films, published musical scores, and lyric operas.

Do not underline other authors’ quotes. Instead, follow the rules given in section 5.3. Underlining too much is like crying wolf: if you do it too many times, nobody will take notice. An underline must always correspond to that special intonation you would give to your voice if you were to read the text. It must attract the attention of your listeners, even if they are distracted.

You can decide to underline (sparingly) single terms of particular technical importance, such as your work’s keywords. Here is an example:

Hjelmslev uses the term sign function for the correlation between two func- tives belonging to the two otherwise independent planes of expression and content. This definition challenges the notion of the sign as an autonomous entity.

Let it be clear that every time you introduce an underlined technical term you must define it immediately before or after. Do not underline for emphasis (“We believe what we have discovered decisively proves our argument that …”). In general, avoid emphasis of any kind, including exclamation points. Also avoid ellipsis points used for anything other than to indicate a specific omission from a text you have quoted. Exclamation points, ellipses used to suspend a thought or sentence, and underlined nontechnical terms are typical of amateur writers and appear only in self-published books.

3. Sections

A section can have a number of subsections, as in this chapter. If you underline the title of a section, not underlining the title of a subsection will suffice to distinguish the two, even if their distance from the text is the same. On the other hand, as you can see, strategic numbering can also help distinguish a section from a subsection. Readers will understand that the first Arabic numeral indicates the chapter, the second Arabic numeral indicates the section, and the third indicates the subsection.

6.1.3.Sections Here I have repeated the title of this subsection to illustrate another system for formatting it. In this system, the title is underlined and run in to the first paragraph of text. This system is perfectly fine, except it prevents you from using the same method for a further subdivision of the subsection, something that may at times be useful (as we shall see in this chapter). You could also use a numbering system without titles. For example, here is an alternative way to introduce the subsection you are reading:

6.1.3. Notice that the text begins immediately after the numbers; ideally, two blank lines would separate the new subsection from the previous one. Notwithstanding, the use of titles not only helps the reader but also requires coherence on the author’s part, because it obliges him to define the section in question (and consequently, by highlighting its essence, to justify it).

With or without titles, the numbers that identify the chapters and the paragraphs can vary. See section 6.4 for more suggestions on numbering. Remember that the structure of the table of contents (the numbers and titles of the chapters and sections) must mirror the exact structure of the text.

4. Quotation Marks and Other Signs

Use quotation marks in the following cases:

- To quote another author’s sentence or sentences in the body of the text, as I will do here by mentioning that, according to Campbell and Ballou, “direct quotations not over three typewritten lines in length are enclosed in quotation marks and are run into the text.”[1]

- To quote another author’s individual terms, as I will do by mentioning that, according to the already-cited Campbell and Ballou, there are two types of footnotes: “content” and “reference.” After the first use of the terms, if we accept our authors’ terminology and adopt these technical terms in our thesis, we will no longer use quotation marks when we repeat these terms.

- To add the connotation of “so-called” to terms of common usage, or terms that are used by other authors. For example, we can write that what idealist aesthetics called “poetry” did not have the same breadth that the term has when it appears in a publisher’s catalog as a technical term opposed to fiction and nonfiction. Similarly we will say that Hjelmslev’s notion of sign function challenges the current notion of “sign.” We do not recommend, as some do, using quotation marks to emphasize a word, as an underline better fulfills this function.

- To quote lines in a dramatic work. When quoting a dramatic work, it is not incorrect to write that Hamlet pronounces the line, “To be or not to be, that is the question, ” but instead we recommend the following:

Hamlet: To be or not to be, that is the question.

Use the second format unless the critical literature that you are consulting uses other systems by tradition.

And how should you indicate a quote within another quote? Use single quotation marks for the quote within a quote, as in the following example, in which according to Smith, “the famous line ’To be or not to be, that is the question’ has been the warhorse of all Shakespearean actors.” And what if Smith said that Brown said that Wolfram said something? Some writers solve this problem by writing that, according to Smith’s well-known statement, “all who agree with Brown in ’refusing Wolfram’s principle that “being and not being coincide”’ incur an unjustifiable error.” But if you refer to rule 8 of section 5.3.1, you will see that, by setting off Smith’s quote from the main text, you will avoid the need for a third level of quotation marks.

Some European writers use a third kind of quotation marks known as guillemets, or French quotation marks. It is rare to find them in an Italian thesis because the typewriter cannot produce them. Yet recently I found myself in need of them in one of my own texts. I was already using double quotation marks for short quotes and for the “so-called” connotation, and I had to distinguish the use of a term as a /signifier/ (by enclosing it in slashes) and as a^signified)^ (by enclosing it in guillemets). Therefore, I was able to write that the word /dog/ means ^(carnivorous and quadruped animal, etc » , and similar statements. These are rare cases, and you will have to make a decision based on the critical literature that you are using, working by hand with a pen in the typewritten thesis, just as I have done in this page.

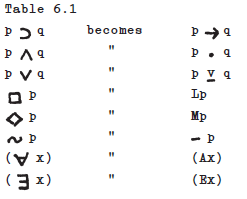

Specific topics require other signs. It is not possible to give general instructions for these, although we can provide some examples here. For some projects in logic, mathematics, or nonEuropean languages, you can only write these signs by hand (unless you own an IBM Selectric electric typewriter, into which you can insert different typeballs that allow you to type different alphabets). This is certainly difficult work. However, you may find that your typewriter can produce alternative graphemes. Naturally, you will have to ask your advisor if you can make these substitutions, or consult the critical literature on your topic. As an example, table 6.1 gives a series of logic expressions (on the left) that can be transcribed into the less laborious versions on the right.

The first five substitutions are also acceptable in print; the last three are acceptable in the context of a typewritten thesis, although you should perhaps insert a note that justifies your decision and makes it explicit.

You may encounter similar issues if you are working in linguistics, where a phoneme can be represented as M but also as /b/. In other kinds of formalization, parenthetical systems can be reduced to sequences of parentheses. So, for example, the expression £C(ppq) A (qsr)3 D (psr)J can become

![]()

can become

![]()

Similarly, the author of a thesis in transformational linguistics knows that he can use parentheses to represent syntactic tree branching. In any case, anyone embarking on these kinds of specialized projects probably already knows these special conventions.

5. Transliterations and Diacritics

To transliterate is to transcribe a text using the closest corresponding letters from an alphabet that is different from the original. Transliteration does not attempt to give a phonetic interpretation of a text, but reproduces the original letter by letter so that anyone can reconstruct the text in its original spelling if they know both alphabets.

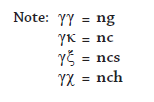

Transliteration is used for the majority of historic geographical names, as well as for words that do not have an English-language equivalent. Table 6.2 shows the rules of transliteration of the Greek alphabet (which can be transliterated, for example, for a thesis in philosophy) and the Cyrillic alphabet (for Russian and some other Slavic languages).

Diacritics are signs that modify normal letters of the alphabet to give them a particular phonetic value. Italian accents are diacritics. For example, the acute accent on the final “e” of the Italian perche gives it its closed pronunciation. Other diacritics include the French cedilla of “9,” the Spanish tilde of “n,” the German dieresis of “u,” and also the less- known signs of other alphabets, such as the Czech “c” or c with hacfek, the Danish or o with stroke, and the Polish “1” or 1 with stroke. In a thesis (on something other than Polish literature) you can eliminate, for example, the stroke on the 1 and the acute accents on the o and z: instead of writing Lodz you can write Lodz. Newspapers also do this. However, for the Latin languages there are stricter rules. Let us look at some specific examples:

Respect the use of all diacritics that appear in the French alphabet, such as the cedilla in £a_ira. Respect the particular signs of the Spanish alphabet: the vowels with the acute accent and the n with tilde “n.” Respect the particular signs of the Portuguese alphabet such as the vowels with the tilde, and the “p.”

Also, always respect the three particular signs of the German alphabet: “a,” ” o,” and “u.” And always write “u,” and not “ue” (Fuhrer, not Fuehrer).

For all other languages, you must decide case by case, and as usual the solution will differ depending on whether you quote an isolated word or are writing your thesis on a text that is written in that particular language.

6. Punctuation, Foreign Accents, and Abbreviations

There are differences in the use of punctuation and the conventions for quotation marks, notes, and accents, even among the major presses. A thesis can be less precise than a typescript ready for publication. Nevertheless, it is useful to understand and apply the general criteria for punctuation. As a model, I will reproduce the instructions provided by Bompiani Editore, the press that published the original Italian version of this book, but we caution that other publishers may use different criteria. What matters here are not the criteria themselves, but the coherence of their application.

Periods and commas.1 When periods and commas follow quotes enclosed in quotation marks, they must be inserted inside the quotation marks, provided that the quoted text is a complete sentence. For example, we will say that, in commenting on Wolfram’s theory, Smith asks whether we should accept Wolfram’s opinion that “being is identical to not being from any possible point of view.” As you can see, the final period is inside the quotation marks because Wolfram’s quote also ended with a period. On the other hand, we will say that Smith does not agree with Wolfram’s statement that “being is identical to not being”. Here we put the period after the quotation mark because only a portion of Wolfram’s sentence is quoted. We will do the

same thing for commas: we will say that Smith, after quoting Wolfram’s opinion that “being is identical to not being”, very convincingly refutes it. And we will proceed differently when we quote, for example, the following sentence: “I truly do not believe,” he said, “that this is possible.” We can also see that a comma is omitted before an open parenthesis.

Therefore, we will not write, “he loved variegated words, fragrant sounds, (a symbolist idea), and velvety pulses” but instead “he loved variegated words, fragrant sounds (a symbolist idea), and velvety pulses”.

Superscript note reference numbers. Insert the superscript note reference number after the punctuation mark. You will therefore write for example:

The best literature review on the topic, second only to Vulpius’, is the one written by Krahehenbuel. The latter does not satisfy Pepper’s standards of “clarity”,3 but is defined by Grumpz4 as a “model of completeness.”

Foreign accents. In Italian, if the vowels “a,” “i,” “o,” and “u” are accented at the end of a word, the accent is grave (e.g. accadra, cos!, pero, gioventh). Instead the vowel “e” at the end of a word almost always requires the acute accent (e.g. perche, poiche, trentatre, affinche, ne, pote) with a few exceptions: e, cioe, caffe, te, ahime, pie, die, stie, scim- panze. All Italian words of French origin also contain grave accents, such as gile, canape, lacche, bebe, bigne, proper nouns such as Giosue, Mose, Noe, and others.(When in doubt, consult a good Italian dictionary.) Also in Italian, tonic accents (subito., principi, meta, era, dei, setta, dai, danno, foll!a, tintinnio) are omitted, with the exception of subito and principi in ambigious sentences:

Tra principi e principi incerti fallirono i moti del 1821.(Between uncertain princes and principles, the uprisings of 1821 failed.)

Also remember that Spanish words have only acute accents: Hernandez, Garcia Lorca, Veron.

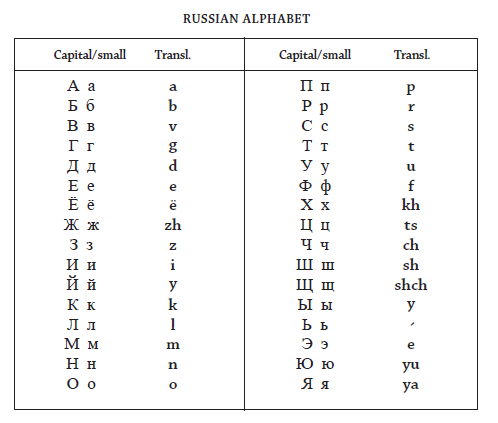

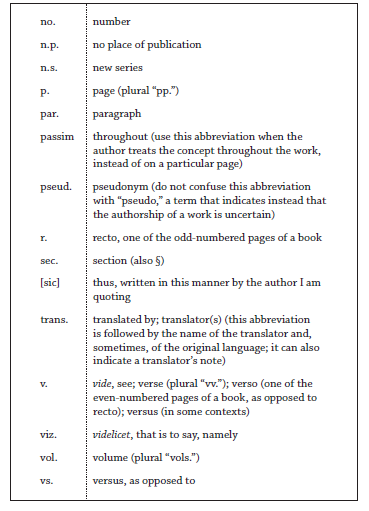

Abbreviations. Table 6.3 provides a list of common abbreviations. Specific subjects (paleography, classical and modern philology, logic, mathematics, etc.) have separate series of abbreviations that you will learn by reading the critical literature on your thesis topic.

7. Some Miscellaneous Advice

Do not capitalize general concepts, and pay attention when you capitalize proper nouns. You can certainly write “Love” and “Hate” if you are examining two precise philosophical notions of an ancient author, but a contemporary author who talks about “the Cult of the Family” uses the capitals only with irony. In a thesis in the field of cultural anthropology, if you wish to dissociate yourself from a concept that you attribute to others, it is preferable to write, “the cult of the family.” For historical periods, refer to the “Revolutionary” period and the “Tertiary” era. Here are some more examples that are generally accepted: write “North America, ” “Black Sea,” “Mount Fuji,” “World Bank,”

“Federal Reserve, ” “Sistine Chapel, ” “House of Representatives, ” “Massachusetts General Hospital, ” “Bank of Labor, ” “European Economic Community,” and sometimes “Central Station.” (Only capitalize the word “station” if it is part of the proper noun. Write “Grand Central Station” for Chicago’s famous central railway station that was recently demolished; but if you are commuting to Boston University from out of state, your train arrives at “Back Bay station.”) Also, write “Magna Carta,” “Bulla Aurea,” and “St. Mark’s Basilica.” Refer to “the Letters of St. Catherine, ” “the Monastery of St. Benedict” and “the Rule of St. Benedict;” and in French, use “Monsieur Teste, ” and “Madame Verdurin.” Italians write “piazza Garibaldi” and “via Roma”; but Americans write “Washington Square Park” and “Wall Street.” Capitalize German common names, as Germans do:

“Ostpolitik,” “Kulturgeschichte.” You must capitalize proper nouns such as “Italians,” “Congolese,” “the Pulitzer Prize,” and “the Holy Father,” but you may write “the bishop,” “the doctor, ” “the colonel, ” “the president, ” “the north,” and “the south.” Generally speaking, you should put everything you can into lower-case letters, as long as you can do so without compromising the intelligibility of the text. For more precise usages, follow the critical literature in the specific discipline you are studying, but be sure to model your text after those published in the last decade.

When you open quotation marks of any kind, always close them. This seems like an obvious recommendation, but it is one of the most common oversights in typewritten texts. A quote begins, and nobody knows where it ends.

Use Arabic numerals in moderation. Obviously this advice does not apply if you are writing a thesis in mathematics or statistics, or if you are quoting precise data and percentages. However, in the middle of a more general argument, write that an army had “50,000” (and not “fifty thousand”) soldiers, but that a work is “comprised of three volumes, ” unless you are writing a reference, in which you should use “3 vols.” Write that the losses have “increased by ten percent, ” that a person has “lived until the ripe old age of 101,” that a cultural revolution occurred in “the sixties,” and that the city was “seven miles away.”

Whenever possible, write complete dates such as “May 17, 1973,” and not “5/17/73.” Naturally you can use abbreviated dates when you must date an entire series of documents, pages of a diary, etc.

Write that a particular event happened at “half past eleven, ” but write that during the course of an experiment, the water had risen approximately “9.8 inches at 11:30 a.m.” Write the matriculation number “7535,” the home at “30 Daisy Avenue,” and “page 144” of a certain book.

Underline only when necessary. As we have said, underline foreign terms that have not been absorbed by English, such as “borgata” or “Einfuhlung.” But do not underline “ciao,” “pasta,” “ballerina,” “opera,” and “maestro.” Do not underline brand names or famous monuments: “the Vespa sped near the Colosseum.” Usually, foreign philosophical terms are not pluralized or declined, even if they are underlined: “Husserl’s Erlebnis” or “the universe of the various Gestalt.” However, this becomes problematic if in the same text you use Latin terms and decline them: “we will therefore analyze all the subiecta and not only the subiectum that is the object of the perceptual experience.” It is better to avoid these difficult situations by using the corresponding English term (usually one adopts the foreign term simply to show off his erudition), or by rephrasing the sentence.

Wisely alternate ordinal and cardinal numbers, Roman and Arabic numerals. Although the practice is becoming less common, Homan numerals can indicate the major subdivision of a work. A reference like “XIII.3” could indicate either volume thirteen, book (or issue) three; or canto thirteen, line three. You can also write “13.3” and the reader will understand you, but “3.XIII” will look strange. You can write “Hamlet III, ii, 28” and it will be clear that you are referring to line twenty-eight of the second scene of the third act of Hamlet, or you can write “Hamlet III, 2, 28” (or “Hamlet 3.2.28”). But do not write “Hamlet 3, II, XXVIII.” Indicate images, tables, or maps as “fig. 1.1” and “table 4.1.”

Reread the typescript! Do this not only to correct the typographical errors (especially foreign words and proper nouns), but also to check that the note numbers correspond to the superscript numbers in the text, and that the page numbers in the works you have cited are correct. Be absolutely sure to check the following:

Pages: Are they numbered consecutively? Cross-references: Do they correspond to the right chapter or page?

Quotes: Are they enclosed in quotation marks, and have you closed all quotations? Have you been consistent in using ellipses, square brackets, and indentations? Is each quote properly cited?

Notes: Does the superscript note reference number in the text correspond to the actual note number? If you are using footnotes, is the note appropriately separated from the body of the text? Are the notes numbered consecutively, or are there missing numbers?

Bibliography: Are authors in alphabetical order? Did you mix up any first and last names? Are all the bibliographical references complete? Did you include accessory details (e.g. the series title) for some entries, but not for others? Did you clearly distinguish books from journal articles and book chapters? Does each entry end with a period?

Source: Eco Umberto, Farina Caterina Mongiat, Farina Geoff (2015), How to write a thesis, The MIT Press.

I like what you guys are up also. Such clever work and reporting! Keep up the superb works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my website :).