Network analysis essentially involves revealing the links that exist between units. These units can be individuals, actors, groups, organizations or projects.

When researchers decide to use network analysis methods, and to look at links between units of analysis, they should be aware that they are implicitly entering into the paradigm of structural analysis. Structural sociology proposes going beyond the opposition that exists in sociology between holistic and individualistic traditions, and for this reason gives priority to relational data.

Analysis methods can be used by researchers taking a variety of different approaches, whether inductive, hypothetico-deductive, static or dynamic. Different ways of using the methods are presented in the first part of this section. Researchers may find they face difficulties that are linked as much to data collection as to the sampling such collection requires. These problems are dealt with in the second part.

1. Using Social Network Analysis Methods

A researcher may often be led to approach a particular management problem by using social network analysis in many different ways. The flexibility of these methods means they can be used inductively or to test a conceptual framework or a set of hypotheses. Moreover, recent developments in network analysis have made it easier to take the dynamics of the phenomena into account.

1.1. Inductive or hypothetico-deductive approaches

The descriptive power of network analysis can make it a particularly apt tool with which to seek a better understanding of a structure. Faced with a reality that can be difficult to grasp, researchers need tools that enable them to interpret this reality, and the data processing methods of network analysis are able to meet this need. General indicators or a sociogram (the graphic representation of a network) can, for example, help researchers to better understand a network as a whole. Calculation of the centrality score or detailed analysis of the sociogram can then enable the central individuals of the structure to be identified. Finally, and still using a sociogram or the grouping methods (which are presented in the second section of this chapter), researchers may reveal the existence of strongly cohesive subgroups within the network (individuals strongly linked to each other), or of groups of individuals who have the same relationships with the other members of the network. Network analysis can thus be used as ‘an inductive method for describing and modeling relational structure [of a network]’ (Lazega, 1994: 293). Lazega’s case study of a firm of business lawyers (see the example below) illustrates the inductive use of network analysis. Studying cliques within this company (groups of individuals in which each is linked to every other member of the clique) enabled him to show how organizational barriers are crossed by small groups of individuals.

With an inductive approach, it is often advisable to use network analysis as a research method that is closely linked to the collection of qualitative data. In fact, as Lazega (1994) underlines, network analysis often only makes sense

when qualitative analysis is also used – to provide the researcher with a real understanding of the context, so that the results obtained can be properly understood and interpreted.

Network analysis is by no means restricted to inductive use. It can, in fact, enable a large number of concepts to be operationalized. There is a great deal of research in which structural data has been used to test hypotheses. For example, centrality scores are often used as explanatory variables in studies of power within organizations. In general, all the methods used in network analysis can be used hypothetico-deductively. Not only are there methods aimed at drawing out individual particularities, but researchers can also use the fact that someone belongs to a subgroup in an organization or network as an explanatory or explained variable. This is what Roberts and O’Reilly are doing when they use a structural equivalence measurement to evaluate whether individuals are ‘active participants’ or not within the United States’ Navy (see example below).

Example: Hypothetico-deductive use of network analysis

In their study conducted within the US Navy, Roberts and O’Reilly (1979) focused on the individual characteristics of ‘participants’ – people who play a communicative role in the organization. Three networks were analyzed, each relating to communication of different kinds of information. One network related to authority, another was a ‘social’ network (unrelated to work) and the third related to expertise. The individual characteristics used were: rank, level of education, length of time they had been in the navy, need to accomplish, need for power, work satisfaction, performance, involvement and perceived role in communications. The hypotheses took the following form: ‘participants have a higher rank than nonparticipants’ or ‘participants have greater work satisfaction than non-participants’. A questionnaire was used to collect both structural data and data on individual characteristics. Network analysis then enabled participant and non-participant individuals to be identified. Actors were grouped into two classes of structural equivalence – participants and non-participants – according to the type of relationship they had with the other people questioned. The hypotheses were then tested by means of discriminant analyses.

1.2. Static or dynamic use of network analysis methods

Network analysis methods have often been criticized for being like a photograph taken at one precise moment. It is, in fact, very rare for researchers to be in a position to conduct a dynamic study of a network’s evolution. This can only be achieved by reconstituting temporal data using an artefact (video-surveillance tapes, for example) or by having access to direct observations on which to base the research. More often, the network observed is a photograph, a static observation. Static approaches can nevertheless lead to very interesting results, as the two examples presented below clearly show. However, references to the role time plays within networks can be found in the literature. Following on from Suitor et al. (1997), many works examine the dynamics of networks, principally asking how this can be taken into account so as to improve the quality of the data collected.

For example, in certain studies, data is collected at successive moments in time. Researchers then present the evolution of the network as a succession of moments in the same way that the construction of discrete variables approximates a continuous phenomenon. This type of research could be aimed at improving our understanding of the stability of networks, and their evolution over time. Here, the researcher seeks to describe or explain the way in which the number of links, their nature or even their distribution evolves. As an illustration, we can cite Welman et al. (1997). Taking a longitudinal approach, they show that neither an individual’s centrality nor a network’s social density are linked to the preservation of the links between actors. Similarly, the fact that a link is strong does not mean it will be long-lasting.

Collecting dynamic data about networks also enables researchers to carry out work for which the implications are more managerial than methodological. For example, Abrahamson and Rosenkopf (1997) propose an approach that enables researchers to track the diffusion of an innovation. Here, the approach is truly dynamic and the research no longer simply involves successive measurements.

2. Data Collection

Data collection is a delicate phase of network analysis. The analyses carried out are, in fact, sensitive to the slightest variations in the network analyzed. Leik and Chalkley (1997) outline some potential reasons for change: the instability inherent in the system (for example, the mood of the people questioned), change resulting from the systems’ natural dynamics (such as maternity leave) and external factors (linked, for example, to the dynamics of the sector of activity). It is, therefore, essential to be extremely careful about the way in which data is collected, the tools that are used, the measurements taken to assess the strength of the links, and how the sample is constructed (how to define the network’s boundaries).

2.1. Collection tools

Network analysis is about relationships between individual or collective units. The data researchers obtain is relational data. In certain situations the collection of such data poses no particular problem – it may be possible to collect data using secondary sources, which often prove to be entirely reliable. This is the case, for example, with research that makes use of the composition of boards of directors or inter-company cooperative ventures. The fact that this type of data is often used indicates that it is reliable relational information that is often relevant and easily accessible. For example, Mizruchi and Stearns (1994) use data on the boards of directors of large American companies taken from Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s annual directories. These directories enabled them to find out who was on the boards of directors and trace the boards’ evolution. The authors were particularly interested in the presence of bank representatives on these boards.

Direct observation is sometimes feasible. One might, for example, study interactions in a particular place such as an office or a tea-room. However, in practice such possibilities for direct observation are quite rare. It is also possible to use certain relational artefacts, such as the minutes of meetings.

Most research based on network analysis uses surveys or interviews to collect data. It is, in fact, difficult to obtain precise data about the nature of the relationships between individuals in the network being analyzed by any other means. The obvious advantage of surveys is that they can reach a large number of people. However, the data collected is often more ‘flimsy’ than that obtained in interviews. The researcher’s presence during the interview means he or she can reply directly to questions raised by the respondent during the research. In an interview situation researchers can also make sure that respondents fully understand what is asked of them and that, from start to finish, they are serious in their replies.

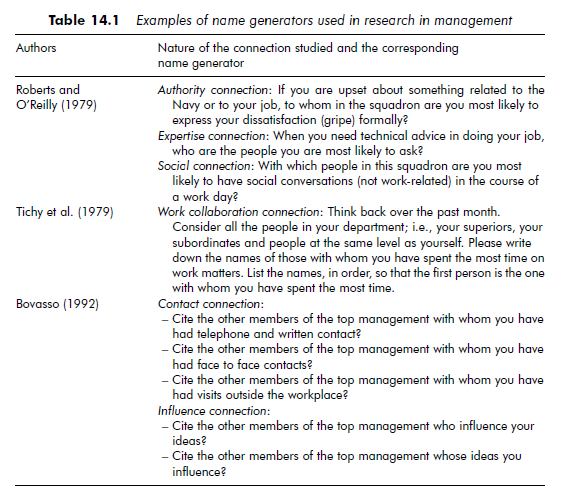

Name generators Whether researchers use surveys or conduct interviews, relational data can be collected by means of ‘name generators’. A name generator is a question either about the links the person being questioned has with the other members of the network or about his or her perception of the links that exist between members of the network. Table 14.1 gives some examples of name generators used in management research. Several collection techniques are possible.

One technique involves asking the respondent to cite the people concerned, possibly in order of importance (or frequency). Researchers can facilitate responses by supplying a list of names (all the members of the organization, for example). Another technique involves asking who they would choose as recipients if a message had to be sent to people with a certain profile.

The use of name generators is a delicate matter. They rely on the respondents’ capacity to recall the actors with whom they are linked in a given type of relationship (for example, the people they have worked with over the past month).

Valued data Not solely the existence, but also the strength of a link can be evaluated. These evaluations produce a valued network. If a flow of information or products circulates among the actors, we also talk about flow measurements. There are a number of ways of collecting this type of data.

The time an interaction takes, for example, can be included in a direct observation of the interaction. Certain secondary data can enable us to assess the strength of a link. If we return to the example of links between boards of directors, the number of directors or the length of time they are on the board can both be good indicators. The following example illustrates another way that secondary data can be used to evaluate the strength of links.

In the many cases in which surveys or interviews are used, researchers must include a specific measurement in their planning to evaluate the strength of relational links. They can do this in two ways. They can either introduce a scale for each relationship, or they can classify individuals in order of the strength of the relationship. The use of scales makes the survey or interview much more cumbersome, but does enable exact evaluation of the links. Likert scales are most commonly used, with five or seven levels ranging, for example, from ‘very frequent’ to ‘very infrequent’ (for more information on scales, see Chapter 9). It is easier to ask respondents to cite actors in an order based on the strength of the relationship, although the information obtained is less precise. In this case, the researcher could use several name generators, and take as the relationship’s value the number of times an individual cites another individual among their n first choices.

Biases To conclude this part of the chapter, we will now examine the different types of biases researchers may face during data collection.

First, there is associative bias. Associative bias occurs in the responses if the individuals who are cited successively are more likely to belong to the same social context than individuals who have not been cited successively. Such a bias can alter the list of units cited and, therefore, the final network. Research has been carried out recently which compares collection techniques to show that this type of bias exists (see, for example, Brewer, 1997). Burt (1997) recommends the parallel use of several redundant generators (that is, relating to relationships of a similar nature). This redundancy can enable respondents to mention a different name, which can in turn prompt them to recall other names.

Another problem researchers face is the non-reciprocity of responses among members of the network. If A cites B for a given relationship, B should, in principle, cite A. For example, if A indicates that he or she has worked with B, B should say that he or she has worked with A. Non-reciprocity of responses can be related to a difference in cognitive perception between the respondents (Carley and Krackhardt, 1996). Researchers must determine in advance a fixed decisionmaking rule for dealing with such non-reciprocity of data. They might, for example, decide to eliminate any non-reciprocal links.

The question also arises of the symmetry of the relationships between individuals. One might expect, for example, that links relating to esteem should be symmetrical. If A esteems B, one might assume that B esteems A. Other relationships, like links relating to giving advice or lending money, are not necessarily reciprocal. It is, however, risky to assume, without verification, that a relationship is symmetrical. Carley and Krackhardt (1996) show that friendship is not a symmetrical relationship.

2.2. Sampling: determining the boundaries and openness of a network

Choosing which individuals to include and setting network boundaries is a delicate area in network analysis. It is very rare for a network to present clearly demarcated natural boundaries. Networks make light of the formal boundaries we try to impose on organizations (structures, flow charts, job definitions, localization, etc.). Consequently, there is bound to be a certain degree of subjectivity involved when researchers delimit the network they are analyzing. Demarcation of the area being studied is all the more important because of the very strong influence this has on the results of the quantitative analyses being conducted (Doreian and Woodard, 1994). Moreover, research into the ‘small world’ phenomenon shows that it is possible, on average, to connect two people chosen at random anywhere in the world by a chain of six links – or six degrees. It is clear, therefore, that if a network is not controlled, it very quickly leads us outside any organizational logic.

For their data to be of any real use, researchers must restrict themselves to a relatively limited field of investigation and obtain the agreement of all (or almost all) of the individuals who enter within this field. While researchers can begin their investigations without having their field of study written in stone, they do have to determine its boundaries sufficiently early on.

According to Laumann et al. (1983), it is possible to specify the boundaries of a network while using either a realist or a nominalist approach. In a realist approach, the researcher adopts the actors’ point of view, and when taking a nominalist approach the researcher adopts certain formal criteria in advance (for example, taking only the first three people cited into account). In both cases, the boundary can be defined in terms of the actors themselves, the relationships between them, or their participation in an activity (a meeting, for example). As a general rule, the research question should serve as a guide in defining the boundaries.

Researchers sometimes need to go beyond this way of thinking about boundaries to take into account the openness of networks. Networks are often analyzed as if they are closed – the actors are considered to be a closed group. However, in many situations this presupposition poses problems.

Doreian and Woodard (1994) propose a systematic process that enables researchers to control sample snowballing. Their method enables researchers to build a sample during the course of their research and to avoid closing off the boundaries of the networks too early, while keeping a check on the individuals included in the network. The first stage consists of obtaining a list of actors included in the network, using strict realist criteria. Those on the list are then asked about the other actors who are essential to their network. Of these new actors, the researcher includes only those who meet a nominalist criterion (for example, taking into account the first three actors cited) – the strictness of the criterion used is determined by the researcher. This criterion is used until no new actors can be included in the network. It is the control the researcher has on the strictness of the nominalist criterion used that enables researchers to halt any snowballing of the sample, and which sets the limits of the network while taking its openness into account from the start.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021