1. GUIDELINES

Now that we have the preliminaries out of the way, we come to the paper itself. Some experienced writers prepare their title and abstract after the paper is written, even though by placement these elements come first. You should, however, have in mind (if not on paper or in the computer) a provisional title and an outline of the paper you propose to write. You should also consider the background of the audience you are writing for so that you will have a basis for determining which terms and procedures need definition or description and which do not. If you do not have a clear purpose in mind, you might go writing off in six directions at once.

It is wise to begin writing the paper while the work is still in progress. This makes the writing easier because everything is fresh in your mind. Furthermore, the writing process itself is likely to point to inconsistencies in the results or perhaps to suggest interesting sidelines that might be followed. Thus, start the writing while the experimental apparatus and materials are still available. If you have coauthors, it is wise to write up the work while they are still available to consult.

The first section of the text proper should, of course, be the introduction. The purpose of the introduction is to supply sufficient background information to allow the reader to understand and evaluate the results of the present study without needing to refer to previous publications on the topic. The introduction

should also provide the rationale for the present study. Above all, you should state briefly and clearly your purpose in writing the paper. Choose references carefully to provide the most important background information. Much of the introduction should be written in present tense because you are referring primarily to your problem and the established knowledge relating to it at the start of your work.

Guidelines for a good introduction are as follows: (1) The introduction should present first, with all possible clarity, the nature and scope of the problem investigated. For example, it should indicate why the overall subject area of the research is important. (2) It should briefly review the pertinent literature to orient the reader. It also should identify the gap in the literature that the current research was intended to address. (3) It should then make clear the objective of the research. In some disciplines or journals, it is customary to state here the hypotheses or research questions that the study addressed. In others, the objective may be signaled by wording such as “in order to determine.” (4) It should state the method of the investigation. If deemed necessary, the reasons for the choice of a particular method should be briefly stated. (5) Finally, in some disciplines and journals, the standard practice is to end the introduction by stating the principal results of the investigation and the principal conclusions suggested by the results.

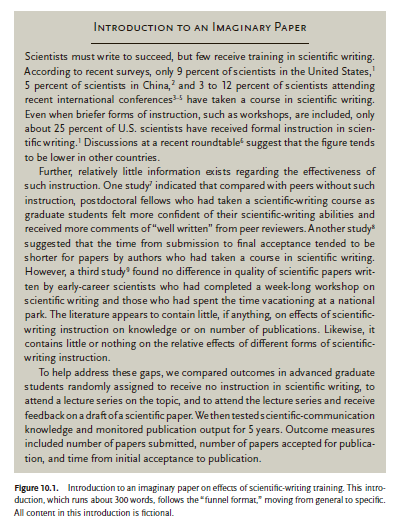

An introduction that is structured in this way (see, for example, Figure 10.1) has a “funnel” shape, moving from broad and general to narrow and specific. Such an introduction can comfortably funnel readers into reading about the details of your research.

2. REASONS FOR THE GUIDELINES

The first four guidelines for a good introduction need little discussion, being reasonably well accepted by most scientist-writers, even beginning ones. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the purpose of the introduction is to introduce the paper. Thus, the first rule (definition of the problem) is the cardinal one. If the problem is not stated in a reasonable, understandable way, readers will have no interest in your solution. Even if the reader labors through your paper, which is unlikely if you haven’t presented the problem in a meaningful way, he or she will be unimpressed with the brilliance of your solution. In a sense, a scientific paper is like other types of journalism. In the introduction, you should have a “hook” to gain the reader’s attention. Why did you choose that subject, and why is it important?

The second, third, and fourth guidelines relate to the first. The literature review, specification of objective(s), and identification of method should be presented in such a way that the reader will understand what the problem was and how you tried to resolve it.

Although the conventions of the discipline and the journal should be followed, persuasive arguments can be made for following the fifth guideline and thus ending the abstract by stating the main results and conclusions. Do not keep the reader in suspense; let the reader follow the development of the evidence. An O. Henry surprise ending might make good literature, but it hardly fits the mold of the scientific method.

To expand on that last point: Many authors, especially beginning authors, make the mistake of holding back their more important findings until late in the paper. In extreme cases, authors have sometimes omitted important findings from the abstract, presumably in the hope of building suspense while proceeding to a well-concealed, dramatic climax. However, this is a silly gambit that, among knowledgeable scientists, goes over like a double negative at a grammarians’ picnic. Basically, the problem with the surprise ending is that the readers become bored and stop reading long before they get to the punch line. “Reading a scientific article isn’t the same as reading a detective story. We want to know from the start that the butler did it.” (Ratnoff 1981, p. 96).

In short, the introduction provides a road map from problem to solution. This map is so important that a bit of redundancy with the abstract is often desirable.

3. EXCEPTIONS

Introductions to scientific papers generally should follow the guidelines that we have noted. However, exceptions exist. For example, whereas the literature review in the introduction typically should be brief and selective, journals in some disciplines favor an extensive literature review, almost resembling a review article within the paper. Some journals even make this literature review a separate section after the introduction—yielding what might be considered an ILMRAD structure.

A colleague of ours tells of reviewing an introduction drafted by a friend in another field. The introduction contained a lengthy literature review, and our colleague advised the friend to condense it. The friend followed the advice— but after she submitted the paper to a journal, the peer reviewers and editor asked her to expand the literature review. It turned out that, unknown to our colleague, her field and her friend’s had different conventions in this regard. I hope that the friend kept earlier drafts (as is a good habit to follow), so she could easily restore some of what had been deleted.

In short, the conventions in your field and the requirements of your target journal take precedence. See what, if anything, the journal’s instructions to authors say about the content and structure of the introduction. Also look at some papers in the journal that report research analogous to yours, and see what the introductions are like.

4. CITATIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS

If you have previously published a preliminary note or abstract of the work, you should mention this (with the citation) in the introduction. If closely related papers have been or are about to be published elsewhere, you should say so in the introduction, customarily at or near the end. Such references help to keep the literature neat and tidy for those who must search it.

In addition to the preceding rules, keep in mind that your paper may well be read by people outside your narrow specialty. Therefore, in general you should define in the introduction any specialized terms or abbreviations that you will use. By doing so, you can prevent confusion such as one of us experienced in the following situation: An acquaintance who was a law judge kept referring to someone as a GC. Calling a lawyer a gonococcus (gonorrhea-causing bacterium) seemed highly unprofessional. It turned out, however, that in law, unlike in medicine, GC stands for “general counsel.”

Source: Gastel Barbara, Day Robert A. (2016), How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, Greenwood; 8th edition.

This web site definitely has all of the information and

facts I needed concerning this subject and didn’t know who to ask.