1. The Exchange Game

The firm as a method of enabling contractors to adjust to change and of encouraging the discovery of new possibilities for mutually advantageous cooperation will be a major theme running through this book. Alongside it there will be developed a different, though complementary, perspective. In section 2 we supposed that a number of people found themselves stranded in unfamiliar circumstances and we argued that generating information about the possibilities technically achievable would be their most important problem. Of equal significance, however, is their lack of information about how far they can trust each other. The possible advantages flowing from cooperative effort through division of labour and exchange were clear enough (sections 3 to 5) but these gains to the group as a whole could only be achieved if people could be relied upon to abide by the terms of an agreement and not to cheat.

Exchange requires that each contractor accepts the right of the other to the resources at present in their possession. Rights to the resources available to people stranded on a desert island would not be well established. No doubt the stranded travellers would apply some of the conventions about property which were familiar in their place of origin. But with no agency to enforce property rights, the danger of a Hobbesian war of all against all would be a real one. Looked at from this perspective, therefore, the assertion in section 2 that the four stranded individuals lacked information about technical possibilities is only one part of the story. They also lack conventions upon which they can rely in their dealings with one another. More generally, they require a trade-sustaining culture.

The difficulty in establishing such a culture can be seen by looking at each potential trade in the form of a game. Two people may see a potential advantage in exchanging x for y. Person C (as in the coalition illustrated in Figure 1.2) might therefore suggest that person D should provide 1.5 units of x and that, after receiving the x, C will return in exchange 1.5 units of y. Person D replies that this is an excellent idea but that it would be even better if C would first provide the 1.5 units of y and that, on receipt of the y, person D would immediately return 1.5 units of x. If neither party is able to trust the other, no trade takes place and the payoff is zero. If both are trustworthy and the trade is honestly made, they will each receive some net benefit from the exchange (let us say this has a value of unity to each person). Finally, if one party mistakenly trusts the other, sending the x or y but receiving nothing in return, the payoff to the cheater we may suppose is two while that to the trusting party is — 1. This structure of payoffs is recorded in Table 1.6.

Person C’s payoffs are given on the left of each pair and person D’s on the right. The game is symmetrical in terms of outcomes. The precise numbers attached to the outcomes are not crucial to the discussion, however. It is the structure of the game as a whole which matters. As presented in Table 1.6, the game of exchange is an example of a prisoner’s dilemma. Consider the situation from the point of view of person C. If D cooperates and provides C with the agreed units of x, person C will receive a higher payoff if he cheats. On the other hand, if D cheats and does not send the agreed units of x, it is still true that person C will do better by also being uncooperative. The worst outcome is to be a ‘sucker’. Cheating is therefore a dominant strategy in a prisoner’s dilemma. This is so even though, from a social point of view, the combined payoff to persons C and D from their both being cooperative exceeds that available from the other alternatives.

Many situations in economic life which require cooperative effort can be modelled in the form of a prisoner’s dilemma. In Chapter 2 the problem of providing public goods is briefly discussed, while in Chapter 4 the difficulty of providing incentives to cooperate in a team activity provides the basis for much of the analysis of Part 2. Here it is necessary merely to note the possible responses to the prisoner’s dilemma which have been suggested and which can be seen reflected in the institutional arrangements which have developed. If cooperation is so difficult, how is it that we observe as much cooperative activity as we do? Four possible answers are proposed below, which will receive varying amounts of attention in future chapters. These may be summarised as the development of reputation, the evolution of norms, the use of outside monitoring and penalties, and finally the creation of a cooperative ethos through leadership.

2. Conventions and Norms

The most obvious objection to the simple exposition of the prisoner’s dilemma in Table 1.6 is that it presents trade as a single, never to be repeated encounter between two people who have no knowledge of each other. If, instead, we consider the possibility that persons C and D might repeat their exchange transaction many times in the future, the game changes its nature. Repeated games or ‘supergames’ can be complex to deal with because the number of possible individual strategies rises exponentially with the number of iterations of the game. It is no longer simply a question of whether to cooperate or cheat in the first round, but whether to cooperate or cheat in the second, conditional upon what had happened in the first and so forth. Nevertheless, both intuition and formal analysis confirm that a sufficiently high probability of repeated dealing will provide a framework in which cooperation can take root.13 The strategy which has attracted the most theoretical attention and which has performed well in simulations of repeated prisoner’s dilemma games is ‘tit for tat’.14

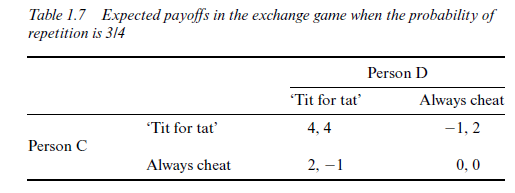

A person playing ‘tit for tat’ cooperates in the first encounter and thereafter cooperates or cheats according to the behaviour of his or her opponent. The obvious advantage of this strategy is that two people playing ‘tit for tat’ will cooperate with one another in the first and all subsequent rounds while limiting their vulnerability to cheaters. Suppose, for example, that after each play of the game there is a probability of 3/4 that another round will be played (that is, there is a one in four chance that it will be the last). The players do not know how many times they will actually play the game but the expected number of iterations will be four. Even this may be enough to make ‘tit for tat’ worth considering as a strategy. The expected payoffs to the players are recorded in Table 1.7.

Clearly, if persons C and D both play ‘tit for tat’ they receive an expected payoff of four each. They both cooperate in round one and then, because each has cooperated, they continue to do so in future rounds. If both cheat in every round their payoff is zero as before. Where one person cheats and the other plays ‘tit for tat’, the latter is exploited in the first round only – the cheater receiving two and the cooperator -1. In subsequent rounds, both cheat and receive zero payoffs.

A sufficiently high probability of repetition thus changes the structure of the exchange game. When confronted with a certain cheater it remains the best strategy to cheat. But cheating is no longer the dominant strategy. If someone is playing ‘tit for tat’ it is better to respond in kind than to cheat. Assuming that it is impossible to know in advance which strategy particular individuals are going to play, strategy choice will depend upon what probability people attach to meeting a person playing ‘tit for tat’. Let the probability of meeting an opponent playing ‘tit for tat’ be p* and the probability of meeting a cheater be (1 -p*). Our expected return to ‘tit for tat’ will then be

4p* + (-1) (1-p*).

Similarly our expected return to cheating will be

2p* + (0) (1-p*).

Thus, ‘tit for tat’ will give us a higher expected payoff providing that

5p* -1 > 2p*

that is

p* > 1/3.

If the probability of meeting a person playing ‘tit for tat’ exceeds 1/3, it will pay us to adopt that strategy also. Thus, once this critical proportion of ‘tit for tat’ strategists in a population is exceeded, there will be a tendency for it to grow. People will learn that cooperation is in their own interests. It is also evident that the higher the probability of repeat dealing, and hence the higher the expected number of iterations of the game, the lower this critical probabilityp* will be. With the payoffs of Table 1.6, if the chance of any given play of the game being the final one is only 1/100 (and hence the expected number of plays is 100) ‘tit for tat’ would give a greater expected return than continual cheating, even if the chance of finding another ‘tit for tat’ player was as low as 1/99. Such are the enormous potential rewards from finding someone cooperative, that quite large losses in first-round plays with cheaters are worth incurring in the search.

It is therefore possible to tell a plausible story about the evolution of cooperative behaviour.15 Mathematical biologists use the concept of the ‘evolutionary stable strategy’ to describe a strategy which is immune to invasion by a group of mutants playing any other strategy (see John Maynard Smith, 1982, Evolution and the Theory of Games). In certain conditions, selfinterested behaviour may result in the widespread adoption of the ‘tit for tat’ strategy in trading games. ‘Tit for tat’ becomes what Sugden (1986) calls a convention. Once established, there are powerful forces of self-interest tending to maintain it, even though alternative conventions might equally well have developed. People comply with established norms of behaviour not necessarily because they think these are worthy of respect from an ethical perspective but because they accord with their own selfish interests.

It can be argued, however, that once conventions have become established they gradually accumulate about them an aura of moral acceptability. People may begin to follow norms of behaviour not merely because it is in their interests to do so but because they believe these norms have moral force.16 They feel they ought to cooperate in the exchange game and would feel a sense of guilt if they did not do so, even in situations where a single round of the game is all that is expected. Tourists, for example, may be in no greater danger of cheating in a small local hotel than in an international chain that hopes to attract their custom again in a different location. In general, however, the existence of the ‘traveller’s tax’ is not widely doubted, although whether it derives from poor knowledge of local conventions on the part of travellers, or poor adherence to more universal conventions on the part of local inhabitants, is perhaps a moot point.

3. Reputation

According to the argument of subsection 8.2, cooperative behaviour developed because successive rounds of the exchange game are played with the same person. The non-repeated prisoner’s dilemma is a game in which the players know nothing of one another except that, in the absence of a moral imperative, the players are virtually impelled to cheat. Repetition enabled knowledge of an opponent to build up, and cheating could be punished by lack of cooperation in the future. Each person was assumed to develop knowledge about other contractors in the market entirely by personal experience. Those playing a ‘tit for tat’ strategy would remember those who had cheated and those who had cooperated on their last acquaintance. This memory would determine the strategy played in any future encounter with these people. Strategy choice becomes, to this extent, personalised.

Clearly the forces leading to cooperation would be greatly reinforced if information about strategy choice in an encounter with one person were available to other potential transactors thereafter. A person observed cheating in the first round would then know that all future encounters would yield nothing, even if these encounters were with ‘new’ opponents. The new opponents would know that the person played the cheating strategy in round one, and would respond with the like strategy in future rounds. People who might otherwise have played ‘tit for tat’ on their first encounter with the cheater will be warned off and will defect. Only a period of cooperation in the face of defection by others might re-establish a person’s ‘standing’ after the initial decision to cheat.

4. Monitoring and Penalties

To achieve a cooperative outcome given the payoffs in the trading game recorded in Table 1.6, something has to happen to change the structure of the game. In subsection 8.2 the possibility of repetition was enough to produce this effect. An obvious alternative is for some third party to monitor compliance with the agreed deal and to punish a transactor who cheats. If this monitor can, for example impose a ‘fine’ in excess of one on anyone who cheats, the payoffs in Table 1.6 will be such that cooperation is the dominant strategy even in a single encounter.

The monitoring solution is particularly likely where information about behaviour is otherwise poor. In the case of our exchange game it is at least clear to each transactor what strategy their opponent has played and the ‘discipline of continuous dealings’ may then be sufficient to ensure cooperative behaviour. In many of the contexts with which we shall be concerned later in this book, however, it may not be possible to tell whether someone has cooperated simply by looking at the outcome of an agreement. Especially when many people are trying to cooperate on some joint enterprise, apportioning responsibility for the final outcome may not be feasible. Transactors again face a prisoner’s dilemma, but the ‘tit for tat’ repeated game solution will not work. Not only may it be impossible to determine who has cooperated and who has not, but the rational response to this information is not obvious. Do I withdraw my cooperation in the next round when a single other person in the group cheats? Or do I cooperate providing a sufficient number of others do likewise? If the latter, how big does the cheating group have to be before I join them?

Where individual behaviour can be fairly accurately gauged by other transactors in a group, and where punishment can be focused on the noncooperative person, the forces of spontaneous order may operate to a degree. In Chapter 10, for example, the use of peer pressure and ‘shame’ to induce cooperative behaviour in a profit-sharing enterprise is discussed. The need for a specialist monitor and enforcer plays a major role in much modern analysis of economic organisation, however. The firm as a device for policing and enforcing contracts will therefore be a continually recurring theme throughout the book.

5. Moral Leadership

Imposing a sufficiently large fine for cheating may, in principle, turn the exchange game from a prisoner’s dilemma into a game of harmonious coordination. It is usual to see the punishment or fine as administered by some monitor as discussed in subsection 8.4. Casson (1991) argues, however, that, especially where the costs of monitoring are high, it is the task of leadership through ‘moral manipulation’ to associate cheating or slacking with a guilt penalty. Thus, the penalty is psychological rather than material. It may be powerful because it operates even in circumstances where a person’s cheating is not discovered by other people. Obviously, if people feel bad about cheating, more possibilities for beneficial exchange will be realised. A trusting culture sustains trade.

We have already seen in section 8.2 that rules having moral force might evolve over time. People might abide by such rules even when flouting them is in their purely material interests. Casson admits that trust can emerge naturally but ‘in many cases it needs to be engineered’ (p. 28). Leaders are in the business of moral propaganda and preference manipulation. Expenditures on guilt-enhancing propaganda are a substitute for monitoring expenditure. Some further discussion of the role of guilt and shame in economic organisation will take place in Chapters 10 and 11, but the role of leadership in setting the general moral climate will not be pursued further.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

Great line up. We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.

I really enjoy looking at on this web site, it holds excellent content. “Beware lest in your anxiety to avoid war you obtain a master.” by Demosthenes.