1. PRODUCTION AND THE FIRM

The firm is not an easy economic concept to define. Everyone accepts that IBM or ICI or Ford constitute ‘firms’, but from an economic as distinct from a purely legal point of view it is necessary to discover what underlying principles enable us to refer to such international giants using the same word as might be used for the local grocer’s retail outlet. Further, if the local grocer’s shop is a ‘firm’ would the same be true of a small hospital run by a charitable foundation, or a church, or even a family? Established textbooks on the principles of economics typically reveal little curiosity about this issue. The firm is simply the fundamental microeconomic unit in the theory of supply. Firms exist and can be recognised by their function, which is to transform inputs of factors of production into outputs of goods and services. With some notable exceptions, the implied asymmetry between the theory of demand, with its emphasis on the individual consumer as the ultimate microeconomic building block, and the theory of supply, with its emphasis on the firm, is rarely explored.

Conventional theory does, however, provide a clue to the nature of ‘the firm’. The process of production usually involves coordinating the activities of different individuals. Suppliers of labour, capital, intermediate inputs, raw materials and land cooperate with one another to produce outputs of goods and services. The institutional setting in which this coordination of activity is attempted may vary enormously, but where economic agents cooperate with one another not through a system of explicit contracts that bind each to every other member of the group but through a system of bilateral contracts in which each comes to an agreement with a ‘single contractual agent’, the essential ingredient of ‘the firm’ is present. It is therefore the nature of the contractual arrangements that bind individuals together which, at least from the point of view of economic theory, constitutes the central preoccupation of the theory of the firm. Much of this book will be concerned to elaborate upon this basic idea and to investigate the insights that flow from it.

2. SCARCITY

Most expositions of elementary economic analysis start with a statement to the effect that economics is concerned with choice. If individuals are confronted by limited resources they must choose between alternatives. Following the definition of Robbins (1935, p. 16), ‘Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.’ As Robbins recognised, this definition is not of very great interest when applied to isolated individuals. A lone individual would have an allocation problem to solve, but a student of such a person’s activities would find it difficult to go further than asserting the proposition that out of all the perceived available courses of action, the isolated decision-maker chooses the alternative that he or she most prefers.

As part of a community of individuals, however, individuals are confronted with a more complex problem. They will usually find that their best strategy is not to cut themselves off from all communication with their fellows, but rather to coordinate their activity with that of other people. Making the best use of scarce resources will therefore involve forming agreements with others, and economics then becomes the study of the social mechanisms which facilitate such agreements. Hidden in this statement, however, are two rather different preoccupations.

First, it is possible to ask in any given situation what particular allocation (or allocations) of resources, what set of agreements, would be best in the sense that no individual or set of individuals within the entire community could gain by opting out and substituting alternative feasible arrangements. Economists express this idea in the technical language of game theory as identifying allocations of resources which are in ‘the core’ of a market exchange game.3 Suppose there were a community of four individuals. Each, we may assume, could live the life of a recluse, but none wishes to do so if cooperation with the others is capable of adding to his or her perceived satisfaction. The four meet and discuss various proposals which will make them all better off. No one will accept a deal which reduces their well-being below that of an isolated recluse, and similarly no final agreement would hold if any two or possibly three out of four could benefit by coming to some alternative arrangement between themselves. A set of agreements which it is in no single individual’s or group’s interests to renounce in favour of an available alternative, is said to be in the ‘core’. Allocations of resources that are ‘core’ allocations represent in one sense a ‘solution’ to the resource allocation problem. Sections 3 to 6, below, present a brief description of this tradition in economics using a very simple example. Proceeding in this way, the unsuitability of the theoretical apparatus of general economic equilibrium for the investigation of economic organisation is thrown into sharp relief.

Economic organisation is more closely concerned with the process by which agreements are formulated. If the tastes and preferences of our four individuals are known to the economist; if their skills and endowments of resources including tools and equipment as well as natural resources, raw materials and land are likewise clearly defined; and if all the feasible options technically available from using these resources in various combinations can be listed, it should be possible in principle to work out all the mutually advantageous agreements which potentially exist. Working out allocations of resources which are in the ‘core’ becomes a matter of mere ‘calculation’. All the necessary information which is formally required to uncover a ‘solution’ is present, and the rest can be accomplished by a sufficiently devoted mathematician or adequately powerful computer. This, though, tells us nothing about the methods adopted by our four individuals to solve their resource allocation problem.

Imagine, for example, that by some fluke of history the four people meet on an otherwise uninhabited island (the sole survivors from four separate shipwrecks). Each person will have little idea of the skills possessed by his or her associates. Indeed each may be in some doubt about his or her own capabilities in the new and unfamiliar environment. The potential of the island to sustain life, the characteristics and uses of the available resources, the best methods of using these resources for various purposes (making clothes, building shelter, finding food, and so on) are all a matter of guesswork and hunch. Setting up the problem in this way makes it clear that what our four individuals lack most is not a calculator, but information.

Facing the appalling problems of survival, the four islanders are likely to agree to cooperate with one another. These agreements will not represent a ‘solution’ to the problem of resource allocation in any ideal sense, since no one can possibly know what the ideal way of proceeding entails. Instead, agreements between the four represent stages in a process of dis- covery.4 As time advances, experience will reveal something of the relative talents of the individuals and the properties and potential of the available resources. Arrangements between the individuals are continually modified in the light of past experience and of expectations about the future. In this framework it is still possible to argue that the subject matter of economics

is the allocation of scarce means between competing uses, but it is clear that the nature of the economic problem when opportunities are not fully known is quite different from the problem conceived of as making the best of available resources in the context of perfect information.

3. THE ALLOCATION PROBLEM

At this stage it will prove useful to develop the theme further by reference to a simple example of the sort frequently encountered in basic textbooks on the principles of economics. We continue to assume that the world consists of four individuals who possess differing endowments of resources. Conventional analysis then proceeds on the assumption that the limited resources available to each individual permit them to produce various known combinations of goods and services. Suppose for simplicity that people desire only two goods (x and y). With the resources at his or her disposal, person A can produce any combination of x and y in the area aa’0 illustrated in Figure 1.1. Given that both x and y confer benefits on person A, it is inconceivable that he or she would choose to produce at any point inside the line aa’. This line aa’ is called person A’s production possibility curve. Its downward slope reflects the fact that the production of more of any one good requires resources to be diverted from the production of the other. The steepness of the curve indicates the amount of y which has to be sacrificed to produce an extra unit of x. In the case of person A, one more unit of x entails the sacrifice of four units of y. Thus the slope of the production possibility curve indicates the marginal opportunity cost of an extra unit of x. If person A produces more x its marginal cost will be 4y. Note that the cost of x can be interpreted as a physical and objective measure (the amount of y forgone) only because we have assumed that all the options available to A are known to him or her with complete certainty.

Each of the other people (labelled B, C and D) will also face constraints on their ability to produce. The constraints are represented by the lines bb’, cc’ and dc’ in Figure 1.1. Notice that some individuals are luckier than others. All points on person B’s production possibility curve are unattainable by any other person. Notice also that the marginal costs of production differ for each person. Person D, for example, is relatively poor but in terms of y sacrificed he or she is the cheapest producer of x.

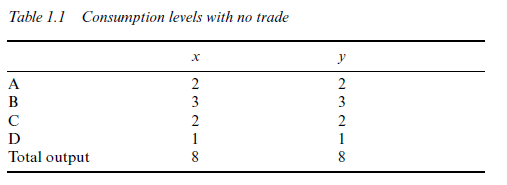

As solitary individuals, each person will have to pick a point on his or her production possibility curve. Suppose, for example, that x and y were not substitutable in consumption and that everyone consumed these goods in fixed proportions (say equal quantities of each). In the absence of trade, consumption points would be given where production possibility curves intersect a 45° line through the origin. The total output of the community will be 8x and 8y. The individual consumption and production levels of each person are recorded in Table 1.1.

One of the most enduring discoveries in economic theory, first fully established by David Ricardo, suggests, however, that these four individuals could do much better through specialisation and exchange. Consider the curve TT in Figure 1.1. This is referred to as the ‘community outer-bound production possibility curve’ or the ‘community transformation curve’. Given the production constraints facing each individual, it is easy to see that if all four people produced product x they could between them achieve 12.5 units of output. If now some y is to be produced, it will entail the sacrifice of some x and it seems reasonable to allocate the person to y production who can produce it at least cost. This person is A, for whom each unit of y will entail the sacrifice of only 0.25 units of x. Person A has the greatest ‘comparative advantage’ in y production of the four individuals. If A specialises in y production and persons B, C and D specialise in x production, the community in total will achieve an output of ten units of x and ten units of y (point A). Further y production can only be achieved by using another person in addition to A. The person who can produce further y at least marginal cost is now person B for whom the marginal cost of y is 0.33x. Complete specialisation of both A and B in y production and of C and D in x production would enable the community to achieve six units of x and 22 units of y (point B). Yet further y production must now involve person C, for whom the marginal cost is 0.5x, and so forth.

Given the rather extreme assumptions we have made about consumption patterns, it is clear that point A will represent the best production point. Specialisation has resulted in an increase of community output of two units of x and two of y.No alternative arrangements exist which would permit the achievement of any points further out along the 45° line. We would expect, therefore, that any agreement between the four individuals would involve A specialising in y production and B, C and D specialising in x production.

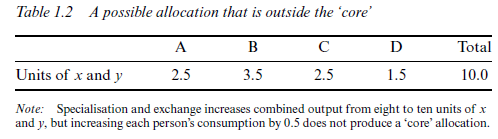

This still leaves open the question of how the benefits of specialisation are to be distributed. We might, for example, envisage one of the transactors making the following suggestion. ‘Since our joint efforts will result in a total increase in output of 2x and 2y above that achievable by our original uncoordinated activity, let us each share equally in this benefit. Final consumption levels would then be as recorded in Table 1.2. All individuals achieve a consumption level 0.5 units higher than those recorded in Table 1.1.

This attempted solution will not work, however. To see why, it is necessary to consider all the trading options available to the various transactors. There is nothing to stop A and B, for example, from getting together and agreeing to collaborate without the others. Similarly, persons C and D might come to a separate agreement. The total output or ‘payoff’ achievable by all the conceivable ‘coalitions’ of people is recorded in Table 1.3.

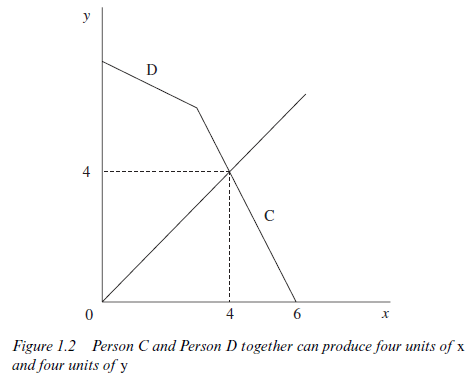

The reader should take an entry at random and check that its meaning is clear.5 If persons C and D collaborated they could achieve a combined output of four units of x and four units of y, as is illustrated in Figure 1.2. D would specialise in x production thus yielding three units of x, while C would produce one unit of x and four units of y. In total, they therefore produce four units of each commodity.

Now consider the position of persons A and D. If they accept the deal offered in Table 1.2 they will join in an agreement which involves all four transactors with a total payoff to the ‘coalition’ of ten units of x and ten of y. Out of this, A will receive 2.5 units of each commodity and D will receive 1.5 units of each, but from Table 1.3 we see that simply by ignoring the others and striking a deal between themselves, A and D could receive a combined payoff of 4.4 units of each commodity instead of the 4.0 of Table 1.2. It follows that the ‘allocation’ of Table 1.2 is not in the ‘core’. Persons A and D could both be better off by renouncing the allocation of Table 1.2 and agreeing an alternative between themselves.

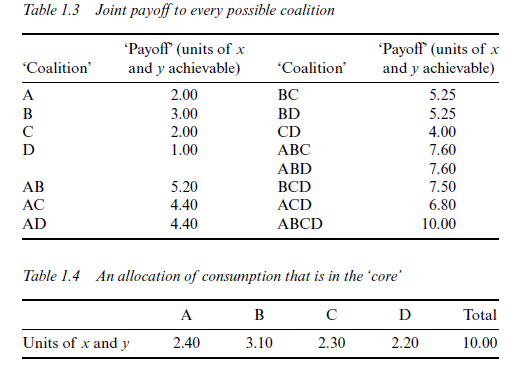

To illustrate the case of an allocation which is in the ‘core’, consider the entries of Table 1.4. Comparing the entries in Table 1.4 with those in Table 1.3, it will be confirmed that no coalition of individuals could do better by striking a separate bargain between themselves. An alliance of B, C and D, for example, could produce a payoff of 7.5, but their combined allocation in Table 1.4 is 7.6. A similar calculation can be performed for every other possible coalition. Thus the allocation of Table 1.4 is in the ‘core’ of the exchange game.

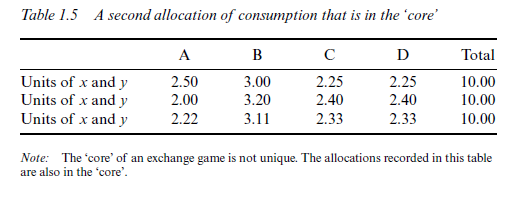

An agreement to specialise in accordance with comparative advantage and then to allocate the output as described in Table 1.4 is therefore one ‘solution’ to the economic problem of making the best out of scarce resources. It is not, however, a unique solution, as the reader can verify by checking the entries of Table 1.5 against those in Table 1.3. The three allocations recorded in Table 1.5 are also in the ‘core’.

4. RECONTRACTING AND THE ALLOCATION PROBLEM

In the section above, attention was focused primarily on calculating a ‘solution’ to the allocation problem under certain specific conditions. Little was said explicitly about the mechanism by which a solution might be achieved. Specialisation implies the existence of a coordinating mechanism by which one person’s activities are made compatible with the actions of others. One mechanism consistent with the example of section 3 is a bargaining process. The four individuals could be seen as initially forming provisional agreements. If it then transpired that alternative more beneficial arrangements were possible for some individual or set of individuals (the provisional agreements did not represent a ‘core’ allocation) then the parties could ‘recontract’. The process of recontracting would continue until it was in no one’s interest to renounce the existing provisional agreement. At this point the agreement would be finalised.6 The provisional agreement summarised in Table 1.2, for example, was renounced by persons A and D. If at the end of further negotiations the agreement summarised in the first line of Table 1.5 were hit upon, this would hold and the process of recontracting would cease.

The recontracting process just described does present some awkward dilemmas for the theorist, however, for if this process means anything, it must imply that the individuals involved possess incomplete information about the production possibilities and preferences of others. If information were perfect, there would be no purpose in conducting ‘negotiations’. All the potential ‘core allocations’ or ‘solutions’ could be computed mathematically, as indeed we computed some in Tables 1.4 and 1.5. The big problem would then be that of choosing between a number of possible known solutions rather than discovering some particular solution or other. Choice between multiple solutions raises extremely difficult issues, since a move from one possibility to another involves some people becoming better off and others worse off (compare lines 1 and 2 of Table 1.5). Which of the many possible options available might eventually be agreed upon is therefore not easy to determine, and it is at least conceivable that no agreement would be forthcoming. Faced with this problem, economic theorists have developed an ingenious escape route. It is possible to show that as the number of contractors in a market increases, then under certain conditions the set of ‘core’ allocations diminishes in size. Indeed, in the limit, with an infinite number of contractors the ‘core’ shrinks to a single allocation.7 No longer is there a problem of choosing between multiple solutions since only a single determinate solution exists.

For a theorist working with the full-information assumption and anxious to show the existence of a unique solution to the allocation problem, a shrinking core is no doubt a matter of some satisfaction. It is difficult to suppress the feeling, however, that where search is a costly activity, the smaller the core the more tiresome and protracted is the process of finding it. In a world in which information is discovered through the process of negotiation there would not appear to be the same compelling reasons to expect any particular outcome to occur. Indeed, it is not even clear that the final agreement will represent a core allocation. After some provisional contracts have been made the parties search around for a better deal. Nothing is finalised until each contractor finds that he or she cannot improve on his or her allocation. This, however, raises the question of how long people are prepared to search for coalitions which improve on their present position. As the number of contractors increases, so the number of potential coalitions increases exponentially and the number of core allocations declines. Any commitment to try all conceivable possibilities could be likely to imply never coming to a final agreed solution.

If the process of forming contracts with one another involves the use of scarce resources, then the ‘best’ use of these scarce resources cannot be said to reside entirely in the discovery of a ‘core’ allocation. A more crucial question concerns how scarce resources are used in the process of contracting itself. Conventional expositions of the recontracting process and the discovery of an allocation of resources which is in the core of the exchange game are therefore suspect. Either the process described is itself a user of scarce resources, in which case it cannot be inferred that search will continue indefinitely until a solution is found, or the process does not use scarce resources, in which case it is merely an unnecessary story to cloak the ‘full-information’ assumption.

5. TATONNEMENT

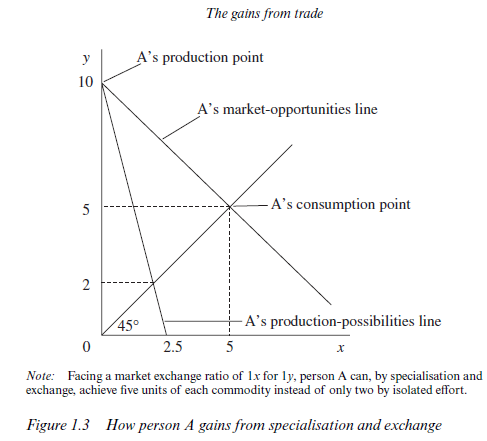

The bargaining framework outlined in sections 3 and 4 deriving from the work of Edgeworth is not the usual approach adopted in elementary treatments of economics. It is more conventional to concentrate on the role of markets and the price system as a device for coordinating activity. Suppose, for example, that all contractors were able to exchange x for y at a ratio of one for one. For every person, the market price of x is one y and vice versa. Returning to Figure 1.1, it is seen that person A must sacrifice only 0.25 units of x in production to obtain a unit of y whereas in the market the price of y is 1x. With the marginal cost to person A of y production so much less than the prevailing price, it will be in his or her interest to specialise in y production and exchange in the market. By this means, the person can achieve a production level of ten units of y and a consumption level of five units of each commodity (see Figure 1.3).

The marginal cost of y production, however, is less than the assumed prevailing market price for both persons B and C as well. Only person D will find it advantageous to specialise in x production, since for him or her the marginal cost of y exceeds the market price (the marginal cost of x on the other hand is less than its market price). Faced, therefore, with this ratio of exchange, the four individuals will be induced to specialise according to their area of comparative advantage and between them they will produce at point C in Figure 1.1.

Given the special nature of consumers’ preferences, however, it is clear that with production of 28 units of y and only three units of x there will be enormous excess demand for x. Equilibrium in the market requires quantities demanded and supplied at the prevailing price to be the same. Clearly a higher price of x relative to y is required to induce persons B and C to change their area of specialisation. Point A will be achieved if the price ratio is set between 3y for 1x and 4y for 1x. A single ratio of exchange applying to all transactors will result in a market equilibrium at point A.

This market ‘solution’ to the resource allocation problem turns out to be closely related to the concept of the ‘core’ mentioned in the last section. Suppose, for example, that the ratio of exchange were 3y for 1x. These market opportunities clearly do not affect person B, since they are exactly the same as the opportunities which confront him or her in production. He/she will continue to consume three units of each commodity. Person A, on the other hand, will specialise in y production (ten units) and exchange 7.5 units of y for 2.5 units of x, thus achieving 2.5 units of each. Both persons C and D will specialise in x (three units each) and exchange 0.75 units for 2.25 units of y, thus achieving 2.25 units of each. Comparing these results with Table 1.5, the reader can verify that they correspond with the entries on the first line. A market ratio of exchange of 3y per 1x will produce an allocation of resources in the conditions specified, equivalent to the first ‘core’ allocation of Table 1.5. As an exercise, the reader should verify that a market rate of exchange of 4y per 1x will produce a result equivalent to the ‘core’ allocation recorded on the second line of Table 1.5. Indeed, it can be rigorously proved that any competitive equilibrium will imply an allocation which is in the ‘core’.8 A given ratio of exchange applying to all contractors of 3.5y per 1x will produce the third allocation of Table 1.5.

This theory of competitive equilibrium, however, suffers from similar difficulties to the exchange theory of Edgeworth discussed above. In its most general form, the theory indicates that there will exist, under specified conditions, a set of relative prices such that individual responses to these given prices will be compatible with equilibrium in every market. The question which the theory does not attempt to answer is precisely how this equilibrium set of prices is to be discovered. As Shackle (1972) puts it ‘what (general equilibrium) theory neglects is the epistemic problem, the problem of how the necessary knowledge on which reason can base itself is to be gained’ (p.447). Like the recontracting process of Edgeworth, the theory of competitive market equilibrium has an equivalent story to tell. In this case it is supposed that an ‘auctioneer’ sets prices and that people form provisional agreements at these given prices. If it transpires that excess demands or supplies exist, the provisional agreements lapse and the auctioneer modifies prices in an attempt to eliminate any disequilibria. This process is termed the ‘tatônnement’ process and is associated primarily with the name of Leon Walras.9

The major problem with the Walrasian auction is not simply that it does not represent an accurate representation of reality. Resource allocation is not conducted by means of Walrasian auctions and, more to the point, the reason why is not difficult to understand. Such a process would be enormously costly. Indeed, such is the complexity characteristic of exchange relationships that an attempt to proceed along Walrasian lines would absorb all the energies and resources of contractors without perhaps ever achieving a ‘solution’. Once more, the paradox of equilibrium theory is exposed. If all information is costlessly available, the auctioneer will get it right first time. If the process of acquiring information is costly, endless pursuit of a general equilibrium is the ultimate example of the ideal becoming the enemy of the good.

6. THE EQUILIBRIUM METHOD

The purpose of our brief discussion of the salient features of general equilibrium theorising conducted above is not to develop a detailed critique or to question the intellectual achievement which it represents. It is important, however, to appreciate the nature of that achievement and the implications which it holds for the theory of the firm and of economic organisation more generally. General equilibrium theory represents an existence proof. Under tightly specified conditions in a world consisting of many individuals all with different tastes, skills and other endowments of resources, there will exist a set of relative prices of goods and factors compatible with universal market clearing. Equivalently there will exist a set of agreements between the individuals which no one will wish to change. The activities of all contractors will be perfectly reconciled. For any given set of preferences, resources and technological possibilities a ‘solution’ to the resource allocation problem exists in terms of specific outcomes.

Such a perfect coordination of all activity requires that agreements are concluded simultaneously and that transactions costs are zero. Knowledge of all technical possibilities both now and in the future must be assumed to be complete. The very passage of time itself can be admitted only in a very artificial sense. By extending the concept of consumers’ preferences to embrace consumption in future time periods, and of production possibilities to include the ‘transformation’ via investment of goods today into goods tomorrow, it is possible to envisage a set of equilibrium intertemporal prices. At some price ratio, the right to consume apples in period 2 may be exchanged for the right to consume nuts in period 5. The final set of agreements will then embrace transactions extending over all future time periods. Time exists as a dimension on a graph, but outcomes over time are completely predetermined at the moment of general agreement. Time is incorporated into the analysis but only at the price of robbing the concept of all meaning. Formally, ‘apples today’ and ‘apples tomorrow’ are simply two different commodities. Decisions concerning consumption and production levels are made ‘now’.

Time implies uncertainty, and the uncertain future poses intractable problems for any theory of rational choice. For general equilibrium theorists, a further extension of the Walrasian system to embrace transactions in ‘state-contingent claims’ is a possibility. Each transactor is assumed to possess a list of all possible future ‘states of the world’ along with some probability estimates attached to each state. Given initial resource endowments, the transactors exchange claims to resources contingent upon specified events. For example, a claim to one kilogram of cocoa in period 3 contingent upon heavy rainfall in Ghana, might exchange in equilibrium for two claims to one kilogram of coffee in period 4 contingent upon no frost in Brazil.

Quite apart from the transactions costs problem mentioned earlier, this effort to achieve a determinate equilibrium in the face of uncertainty encounters even more fundamental difficulties. For the transactors are ‘unboundedly rational’. All possible future states of the world are imaginable and nothing can occur which has not been imagined. Yet, when the future is concerned, there would appear to be no limits on the agenda of possible events, no boundaries on the contingencies which might be considered. Decision-making in the face of such uncertainty cannot then be rational in the sense of making one best choice in the face of known opportunities. To quote Shackle (1972): ‘it is plain that in order to achieve a theory of value applicable to the real human situation, reason must compromise with time’ (p. 269).

7. INSTITUTIONS AND INFORMATION

For the purposes of the theory of the firm, the important point about the general equilibrium method is that by effectively excluding time and uncertainty from the analysis, all transactions are costlessly and instantaneously reconciled. In this environment there are no institutional structures called firms. The efforts of all individuals are coordinated by a gigantic and complex web of contractual commitments simultaneously entered into. The economy is made up of a myriad of individual contractors, each one in an intricate and complex pattern of interrelationships with every other. As a description of economic life, however, this is clearly not very accurate. Institutions such as firms, clubs, political parties, trade unions and bureaucracies exist, and their existence, if it is not to be left unexplained or put down to chance, can be viewed as the outcome of the attempts by rational individuals to solve the resource allocation problems which confront them.

If firms help in the process of resource allocation they must represent a response to factors from which general equilibrium theory abstracts. The economy, to use the analogy of Simon (1969) and Loasby (1976), is not like a watch made up of thousands of parts placed separately in an appropriate position relative to all the others, but is more equivalent to a mechanism made up of several subassemblies, the operating principles of which may be analysed separately even if their ultimate purposes may be fully understood only in the context of the complete item. A system of subassemblies places limits on the number of linkages which must simultaneously be considered and thereby reduces the costs of establishing them.

Firms are formed and survive as an institutional response to transactions costs. In a world of costless knowledge they have no rationale, but in a world in which opportunities are continually being discovered and in which the formation of agreements between individuals is a costly activity, firms may be seen as devices for reducing the costs of achieving coordinated effort. The ways in which transactions costs are reduced and the problems which arise as a result will be discussed in greater detail in future chapters. For present purposes it is sufficient to remember that ‘firms’ are characterised by a system of bilateral contracts. Each person comes to an agreement with ‘the firm’. In the case of a small business a single proprietor might be the central contractual agent. In more complex cases the agreement will be between employees, managers, bondholders or landowners and a ‘legal fiction’ such as BP or US Steel. The firm is a ‘nexus of contracts’.10

The nature of this set of contracts is of very great importance. They are not highly specific contracts. They will not normally lay down extremely detailed provisions concerning when, where and how particular tasks are to be performed. When we join a firm as an employee we agree, within certain limits, to do whatever we are asked to do. We agree to be ‘organised’. When we join as a manager we agree to organise resources, and have considerable discretion as to the way this may be done. Contracts, in other words, are imperfectly specified. This lack of specificity derives from the simple fact that the precise details of the actions required of the employees of a firm may be unknown at the time the contract is made. The decisionmaking process continues through time, and only time will reveal the decisions which may be made in the future concerning the best plan of action for the firm. If contracts had to be renegotiated with every small change of policy, the firm as a useful device for allocating resources would disappear.

Within the firm, information is collected concerning opportunities for productive collaboration, on the skills and attributes of employees, on new technical innovations, on the demands of consumers and so forth. This information must be transmitted to the relevant decision-makers who must then choose and implement a plan of action. Resource allocation within the firm is not therefore the outcome of entirely decentralised decisions by individual people in response to their particular circumstances as in a market process. Nor is it the result of simultaneous agreement between all contractors as in a state of general equilibrium. Resources within firms are allocated by the conscious decisions of planners. The market process is replaced in the firm by a planning process. Firms are ‘islands of conscious power in an ocean of unconscious co-operation’ to use D.H. Robertson’s vivid metaphor.11

It is important for readers to recognise that this initial characterisation of the firm will be amended in important respects in future chapters. As presented here, our definition depends upon a clear distinction being possible between a ‘market process’ and a ‘planning process’. Later, we shall question whether a clear dividing line can be drawn, and we will investigate in greater detail the spectrum of contractual relations which ranges from relatively arm’s length market types towards contracts involving more ‘firm-like’ characteristics.12 Certainly it should not be inferred from the above paragraph that firms must be monolithic organisations with highly centralised planning arrangements. As will be seen in Chapters 6 and 7, contractual relations can vary substantially both within and between firms.

The existence of firms suggests, however, that up to a point, at least, a structure of loosely specified and durable contracts with a central agent may have advantages over the market. Groups of people may find it expedient to accept these arrangements if they permit the more effective generation and use of information. It can be advantageous to be told what to do if the decision-making processes used within the firm make it possible to coordinate activities more productively than would otherwise be possible.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

Some genuinely superb info , Glad I detected this.