Let us suppose that you have persuaded all your project sponsors to give honest forecasts. Although those forecasts are unbiased, they are still likely to contain errors, some positive and others negative. The average error will be zero, but that is little consolation because you want to accept only projects with truly superior profitability.

Think, for example, of what would happen if you were to jot down your estimates of the cash flows from operating various lines of business. You would probably find that about half appeared to have positive NPVs. This may not be because you personally possess any superior skill in operating jumbo jets or running a chain of laundromats but because you have inadvertently introduced large errors into your estimates of the cash flows. The more projects you contemplate, the more likely you are to uncover projects that appear to be extremely worthwhile.

What can you do to prevent forecast errors from swamping genuine information? As a senior manager, you can’t be expected to check every cash-flow forecast, but you can ask some questions to ensure that each project truly does have a positive NPV. We suggest that you begin by looking at market values.

1. The BMW and Your Sporting Idol

The following parable should help to illustrate what we mean. Your local BMW dealer is announcing a special offer. For $85,000, you get not only a brand-new BMW 6-Series convertible, but also the chance to enjoy a day’s coaching from your favorite sporting hero. You wonder how much you are paying for that day.

There are two possible approaches to the problem. You could evaluate each of the BMW’s features, starting with the Turbo V8 engine and ending with the exclusive Nappa leather interior, and conclude that the car is worth $80,000. This would seem to suggest that the day with your sporting hero is costing you $5,000. Alternatively, you might nip round to a couple other BMW dealers and discover that the going market price for the car is $85,000 so that the special offer is costing you nothing. As long as there is a competitive market for BMWs, the latter approach makes more sense.

Security analysts face a similar problem whenever they value a company’s stock. They must consider the information that is already known to the market about a company, and they must evaluate the information that is known only to them. The information that is known to the market is the BMW; the private information is the day with your sporting idol. Investors have already evaluated the information that is generally known. Security analysts do not need to evaluate this information again. They can start with the market price of the stock and concentrate on valuing their private information.

While lesser mortals would instinctively accept the BMW’s market value of $85,000, the financial manager is trained to enumerate and value all the costs and benefits from an investment and is therefore tempted to substitute his or her own opinion for the market’s. Unfortunately, this approach increases the chance of error. Many capital assets are traded in a competitive market, so it makes sense to start with the market price and then ask why you can earn more than your rivals from these assets.

EXAMPLE 11.1 ● Investing in a New Department Store

We encountered a department store chain that estimated the present value of the expected cash flows from each proposed store, including the price at which it could eventually sell the store. Although the firm took considerable care with these estimates, it was disturbed to find that its conclusions were heavily influenced by the forecasted selling price of each store. Management disclaimed any particular real estate expertise, but it discovered that its investment decisions were unintentionally dominated by its assumptions about future real estate prices.

Once the financial managers realized this, they always checked the decision to open a new store by asking the following question: “Let us assume that the property is fairly priced. What is the evidence that it is best suited to one of our department stores rather than to some other use?” In other words, if an asset is worth more to others than it is to you, then beware of bidding for the asset against them.

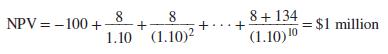

Let us take the department store problem a little further. Suppose that the new store costs $100 million.[1] You forecast that it will generate after-tax cash flow of $8 million a year for 10 years. Real estate prices are estimated to grow by 3% a year, so the expected value of the real estate at the end of 10 years is 100 X (1.03)10 = $134 million. At a discount rate of 10%, your proposed department store has an NPV of $1 million:

Notice how sensitive this NPV is to the ending value of the real estate. For example, an ending value of $120 million implies an NPV of -$5 million.

It is helpful to imagine such a business as divided into two parts—a real estate subsidiary that buys the building and a retailing subsidiary that rents and operates it. Then figure out how much rent the real estate subsidiary would have to charge, and ask whether the retailing subsidiary could afford to pay the rent.

In some cases, a fair market rental can be estimated from real estate transactions. For example, we might observe that similar retail space recently rented for $10 million a year. In that case, we would conclude that our department store was an unattractive use for the site. Once the site had been acquired, it would be better to rent it out at $10 million than to use it for a store generating only $8 million.

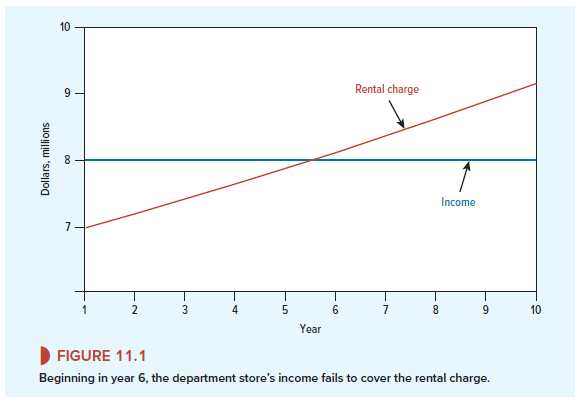

Suppose, on the other hand, that the property could be rented for only $7 million per year. The department store could pay this amount to the real estate subsidiary and still earn a net operating cash flow of 8 – 7 = $1 million. It is therefore the best current use for the real estate.[2]

Will it also be the best future use? Maybe not, depending on whether retail profits keep pace with any rent increases. Suppose that real estate prices and rents are expected to increase by 3% per year. The real estate subsidiary must charge 7 X 1.03 = $7.21 million in year 2, 7.21 X 1.03 = $7.43 million in year 3, and so on.[3] Figure 11.1 shows that the store’s income fails to cover the rental after year 5.

If these forecasts are right, the store has only a five-year economic life; from that point on, the real estate is more valuable in some other use. If you stubbornly believe that the department store is the best long-term use for the site, you must be ignoring potential growth in income from the store.[4]

There is a general point here as illustrated in Example 11.1. Whenever you make a capital investment decision, think what bets you are placing. Our department store example involved at least two bets—one on real estate prices and another on the firm’s ability to run a successful department store. But that suggests some alternative strategies. For instance, it would be foolish to make a lousy department store investment just because you are optimistic about real estate prices. You would do better to buy real estate and rent it out to the highest bidders. The converse is also true. You shouldn’t be deterred from going ahead with a profitable department store because you are pessimistic about real estate prices. You would do better to sell the real estate and rent it back for the department store. We suggest that you separate the two bets by first asking, “Should we open a department store on this site, assuming that the real estate is fairly priced?” and then deciding whether you also want to go into the real estate business.

Let us look at another example of how market prices can help you make better decisions.

EXAMPLE 11.2 ● Opening a Gold Mine

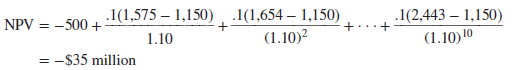

Kingsley Solomon is considering a proposal to open a new gold mine. He estimates that the mine will cost $500 million to develop and that in each of the next 10 years, it will produce 1 million ounces of gold at a cost, after mining and refining, of $1,150 an ounce. Although the extraction costs can be predicted with reasonable accuracy, Mr. Solomon is much less confident about future gold prices. His best guess is that the price will rise by 5% per year from its current level of $1,500 an ounce. At a discount rate of 10%, this gives the mine an NPV of -$35 million:

Therefore, the gold mine project is rejected.

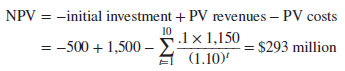

Unfortunately, Mr. Solomon did not look at what the market was telling him. What is the PV of an ounce of gold? Clearly, if the gold market is functioning properly, it is the current price, $1,500 an ounce. Gold does not produce any income, so $1,500 is the discounted value of the expected future gold price.8 Since the mine is expected to produce a total of 1 million ounces (.1 million ounces per year for 10 years), the present value of the revenue stream is 1 X 1,500 = $1,500 million.[8] [9] Suppose that 10% is an appropriate discount rate for the relatively certain extraction costs. Then

It looks as if Kingsley Solomon’s mine is not such a bad bet after all.

Mr. Solomon’s gold, in Example 11.2, was just like anyone else’s gold. So there was no point in trying to value it separately. By taking the PV of the gold sales as given, Mr. Solomon was able to focus on the crucial issue: Were the extraction costs sufficiently low to make the venture worthwhile? That brings us to another of those fundamental truths: If others are producing a good or service profitably and (like Mr. Solomon) you can make it more cheaply than them, then you don’t need any NPV calculations to know that you are probably onto a good thing.

We confess that our example of Kingsley Solomon’s mine is somewhat special. Unlike gold, most commodities are not kept solely for investment purposes, and therefore you cannot automatically assume that today’s price is equal to the present value of the future price.11

However, here is another way that you may be able to tackle the problem. Suppose that you are considering investment in a new copper mine and that someone offers to buy the mine’s future output at a fixed price. If you accept the offer—and the buyer is completely creditworthy—the revenues from the mine are certain and can be discounted at the risk-free interest rate.12 That takes us back to Chapter 9, where we explained that there are two ways to calculate PV:

- Estimate the expected cash flows and discount at a rate that reflects the risk of those flows.

- Estimate what sure-fire cash flows would have the same values as the risky cash flows.

Then discount these certainty-equivalent cash flows at the risk-free interest rate.

When you discount the fixed-price revenues at the risk-free rate, you are using the certainty-equivalent method to value the mine’s output. By doing so, you gain in two ways: You don’t need to estimate future mineral prices, and you don’t need to worry about the appropriate discount rate for risky cash flows.

But here’s the question: What is the fixed price at which you could agree today to sell your future output? In other words, what is the certainty-equivalent price? Fortunately, for many commodities, there is an active market in which firms fix today the price at which they will buy or sell copper and other commodities in the future. This market is known as the futures market, which we will cover in Chapter 26. Futures prices are certainty equivalents, and you can look them up in the daily newspaper. So you don’t need to make elaborate forecasts of copper prices to work out the PV of the mine’s output. The market has already done the work for you; you simply calculate future revenues using the price in the newspaper of copper futures and discount these revenues at the risk-free interest rate.

Of course, things are never as easy as textbooks suggest. Trades in organized futures exchanges are largely confined to deliveries over the next year or so; therefore, your newspaper won’t show the price at which you could sell output beyond this period. But financial economists have developed techniques for using the prices in the futures market to estimate the amount that buyers would agree to pay for more-distant deliveries.[11]

Our two examples of gold and copper producers are illustrations of a universal principle of finance: When you have the market value of an asset, use it, at least as a starting point in your analysis.

25 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

23 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021