Profits that more than cover the cost of capital are known as economic rents. Economics 101 teaches us that in the long run, competition eliminates economic rents. That is, in a long-run competitive equilibrium, no company can expand and earn more than the cost of capital on that investment.

Economic rents are earned when an industry has not settled down to equilibrium or when your firm has something valuable that your competitors don’t have. For example, suppose that demand takes off unexpectedly and that your firm can expand production capacity more quickly and cheaply than your competitors. This stroke of luck is pretty sure to generate economic rents, at least until other firms manage to catch up.

Some competitive advantages are longer lived. They include patents or proprietary technology; reputation, embodied in respected brand names, for example; economies of scale that customers can’t match; protected markets that competitors can’t enter; and strategic assets that competitors can’t easily duplicate.

Here’s an example of strategic assets. Think of the difference between railroads and trucking companies. It’s easy to enter the trucking business but nearly impossible to build a brand- new, long-haul railroad.[1] The interstate lines operated by U.S. railroads are strategic assets. With these assets in place, railroads were able to increase revenues and profits rapidly when shipments surged and energy prices increased in the early years of this century. The high cost of diesel fuel was more burdensome for trucks, which are less fuel efficient than railroads. Thus, high energy prices actually handed the railroads a competitive advantage.

Corporate strategy aims to find and exploit sources of competitive advantage. The problem, as always, is how to do it. John Kay advises firms to pick out distinctive capabilities— existing strengths, not just ones that would be nice to have—and then identify the product markets where those capabilities can generate the most value added. The capabilities may come from durable relationships with customers or suppliers, from the skills and experience of employees, from brand names and reputation, and from the ability to innovate.[2]

Michael Porter identifies five aspects of industry structure (or “five forces”) that determine which industries are able to provide sustained economic rents.[3] These are the rivalry among

existing competitors, the likelihood of new competition, the threat of substitutes, and the bargaining power both of suppliers and customers. With increasing global competition, firms cannot rely so easily on industry structure to provide high returns. Therefore, managers also need to ensure that the firm is positioned within its industry so as to secure a competitive advantage. Porter goes on to suggest three ways this can be done—by cost leadership, by product differentiation, and by focus on a particular market niche.[4]

These advantages will protect a firm only if they are durable and can be sustained against competition from other businesses. Warren Buffett stresses that successful businesses require the equivalent of a castle moat to deter marauders:

I want a business with a moat around it with a very valuable castle in the middle. And then I want the duke who’s in charge of that castle to be honest and hard-working and able. . . .

Our managers of the businesses we run, I’ve got one message to them, which is to widen the moat. And we want to throw crocodiles and sharks and everything else, gators, I guess, into the moat to keep away competitors. And that comes about through service, it comes about through quality of product, it comes about through cost, it comes about sometimes through patents, it comes about through real estate location.[5]

You can see how business strategy and finance reinforce each other. Managers who have a clear understanding of their firm’s competitive strengths (and the moats that protect their products and services) are better placed to separate those projects that truly have a positive NPV from those that do not. Therefore, when you are presented with a project that appears to have a positive NPV, do not just accept the calculations at face value. They may reflect simple estimation errors in forecasting cash flows. Probe behind the cash-flow estimates, and try to identify a source of economic rents. A positive NPV for a new project is believable only if you believe that your company has some special advantage.

Thinking about competitive advantage can also help ferret out negative-NPV calculations that are negative by mistake. For example, if you are the lowest-cost producer of a profitable product in a growing market, you should invest to expand along with the market. If your calculations show a negative NPV for such an expansion, you have probably made a mistake.

We will work through shortly an extended example that shows how a firm’s analysis of its competitive position confirmed that a major investment had a positive NPV. But first we look at an example in which the analysis helped a firm to identify a negative-NPV transaction and avoid a costly mistake.

EXAMPLE 11.3 ● How One Company Avoided a $100 Million Mistake

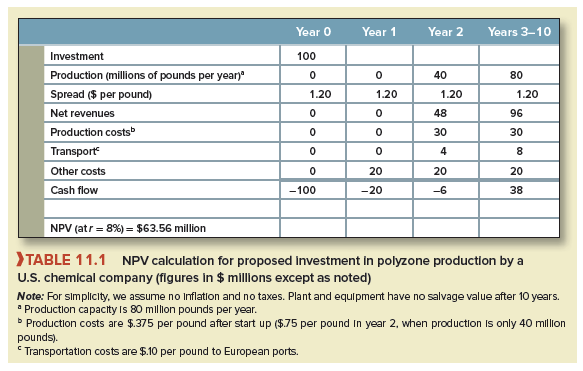

A U.S. chemical producer was about to modify an existing plant to produce a specialty product, polyzone, which was in short supply on world markets.[6] At prevailing raw material and finished-product prices, the expansion would have been strongly profitable. Table 11.1 shows a simplified version of management’s analysis. Note the assumed constant spread between selling price and the cost of raw materials. Given this spread, the resulting NPV was about $64 million at the company’s 8% real cost of capital—not bad for a $100 million outlay.

Then doubt began to creep in. Notice the outlay for transportation costs. Some of the project’s raw materials were commodity chemicals, largely imported from Europe, and much of the polyzone production would be exported back to Europe. Moreover, the U.S. company had no long-run technological edge over potential European competitors. It had a head start perhaps, but was that really enough to generate a positive NPV?

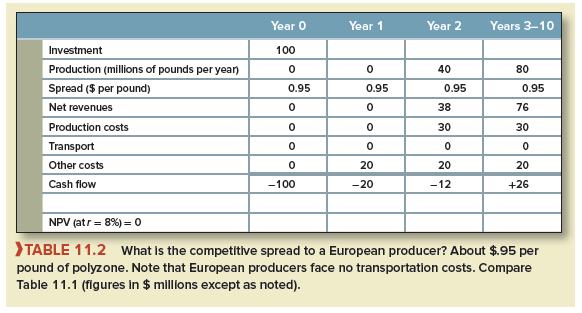

Notice the importance of the price spread between raw materials and finished product. The analysis in Table 11.1 forecasted the spread at a constant $1.20 per pound of polyzone for 10 years. That had to be wrong: European producers, who did not face the U.S. company’s transportation costs, would see an even larger NPV and expand capacity. Increased competition would almost surely squeeze the spread. The U.S. company decided to calculate the competitive spread—the spread at which a European competitor would see polyzone capacity as zero NPV. Table 11.2 shows management’s analysis. The resulting spread of about $.95 per pound was the best long-run forecast for the polyzone market, other things constant of course.

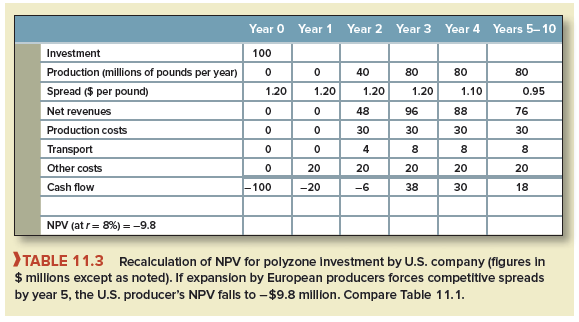

How much of a head start did the U.S. producer have? How long before competitors forced the spread down to $.95? Management’s best guess was five years. It prepared Table 11.3, which is identical to Table 11.1 except for the forecasted spread, which would shrink to $.95 by the start of year 5. Now the NPV was negative.

The project might have been saved if production could have been started in year 1 rather than 2 or if local markets could have been expanded, thus reducing transportation costs. But these changes were not feasible, so management canceled the project, albeit with a sigh of relief that its analysis had not stopped at Table 11.1.

This is a perfect example of the importance of thinking through sources of economic rents. Positive NPVs are suspect without some long-run competitive advantage. When a company contemplates investing in a new product or expanding production of an existing product, it should specifically identify its advantages or disadvantages over its most dangerous competitors. It should calculate NPV from those competitors’ points of view. If competitors’ NPVs come out strongly positive, the company had better expect decreasing prices (or spreads) and evaluate the proposed investment accordingly.

Keep functioning ,impressive job!

I love what you guys tend to be up too. Such clever work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to blogroll.

I like this post, enjoyed this one thanks for posting.