1. Inter-Organizational Relationships

In general, a network is a model or metaphor that describes a number of entities that are connected (Axels- son & Easton 1992). In the case of international industrial networks, the entities are actors involved in the economic process that converts resources into finished goods and services. The network model is based on the assumption that a firm’s changing internationalization situation is a result of its positioning in a network of firms and their connections to each other (Zuchella & Scabini 2007). The market is depicted as systems of social and industrial relationships among various parties. The network concept encompasses a firm’s set of relationships, both horizontal and vertical, with other entities, such as system and component suppliers, manufacturers, merchandisers, customers, and competitors, and includes relationships across industries and countries (Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer 2000; Windeler 2005). By entering global networks, firms gain international knowledge through learning from other network actors, which assumes the establishment, development and protection of international business relations (Hakansson & Johanson 2001; Mathews 2002; Samiee 2008).

Learning Through Relationships

Internationalization is a process of increasing involvement in international operations, which results in an accumulation of knowledge about markets and institutions abroad (Ellis 2000; Welch & Luostarinen 1988). Modern internationalization processes are particularly characterized as a course of learning through network relationships (Sharma & Blomstermo 2003).

The network perspective draws attention to long-term business activities that exist among firms such as suppliers and customers in industrial markets. While the traditional Uppsala approach focuses on the circumstances and internationalization process of the individual firm, the network theory pays attention to the firm’s interconnections with local and foreign units (Bjorkman & Forsgren 2000; Zuchella & Scabini 2007). Through its ‘combinative capability,’ a firm exploits knowledge (collected in industry networks) for expansion into new markets. Thus, the efficient organization of knowledge transfer among the firm units is of vital importance for business performance (Kogut & Zander 1993; Zuchella & Scabini 2007).

Networks among buyers and sellers, which form the basis of effective communication, have to be established, thus providing firms with the opportunity and motivation to internationalize. Relevant information disseminates via social interaction (Ellis 2000). The nature of relationships influences the strategic decisions of the participating firms (Coviello & Munro 1997). Relationship-based strategies for market entry range from longterm oriented licensing agreements and contract manufacturing to international joint ventures with two or more partners (Mathews 2002).

1.1. The Impact of the Resource-Based View

The resource-based view (RBV) holds that a firm acquires competitive characteristics not simply as a function of its market location, such as its position in the value chain within a certain industry (compare: Penrose 1959). Competitive advantages are particularly derived from a firm’s ‘inner resources’ (e.g., managerial, organizational, technological resources, etc.) as well as from the firm’s capacity to absorb and integrate ‘external resources’ through relationships (Fahy 2002; Mathews 2002; Wernerfelt 1984).

According to Barney (1991), a firm’s resources should have the following attributes to gain sustained competitive advantage.

How to gain competitive advantage according to the resource-based view

- The first attribute is resource value. Resources are valuable when they enable a firm to conceive of or implement strategies that improve efficiency and effectiveness.

- Second, resources need to be rare, which means that current and potential competitors cannot rely simultaneously on them. A firm enjoys a competitive advantage when it is implementing a value-creating strategy that cannot be implemented by a large number of competitors that have limited access to the necessary resources (e.g., technological knowledge).

- Third, sustained competitive advantage can be reached ifvaluable resources can only be imperfectly imitated by competitors.

- Finally, rare and valuable resources cannot be substituted by competitors who are able to implement strategically equivalent resources (Barney 1991).

Consequently, the assumption that more knowledge would be likely to improve the efficiency and profitability of the firm acts as an incentive to acquire new knowledge and shape the scope and direction in the firm’s search for knowledge inside and outside its own organization (Penrose 1995). Based on the foundations of the RBV, Grant (1991b) argues that the fundamental prerequisite for market power is the presence of market entry barriers based upon a firm’s resources in the market, as for example scale economies, patents, international experience advantages, and brand reputation. The ability to establish a cost advantage requires possession of scale-efficient operations, superior process technology, ownership of low-cost sources of raw materials or access to low-wage labor. Differentiation advantage is conferred by superior quality and innovative products and services linked with proprietary technology or an extensive sales and service network.

The RBV perceives the firm as a unique bundle of idiosyncratic resources and capabilities where the primary task of management is to maximize value through the optimal deployment of existing resources and capabilities. In line with RBV, particular fostering of the knowledge resource is of vital importance in order for the firm to gain a competitive advantage. Grant (1996) describes ‘knowing how’ as ‘tacit knowledge’ and ‘knowing about facts and theories’ as ‘explicit knowledge.’ The critical distinction between the two lies in transferability and the mechanisms for transfer across individuals, space, and time. Explicit knowledge is revealed by its communication and tacit knowledge through application. Communication efficiency is a fundamental resource property, thus an important strength of the firm. At both individual and organizational levels, knowledge absorption depends upon a recipient’s ability to add new knowledge to existing knowledge (Grant 1996).

Knowledge transferability is important, not only between firms such as suppliers and customers, but even more critically, within the firm. Consequently, the creation of tacit knowledge and the ability to transfer it effectively within the organization, which includes its foreign operations, should move into the focus of the management (Chwialkowska & Ganiyu 2017). Transmission capacity is defined as the ability of a firm (or the relevant business unit within it) to articulate uses of its own knowledge, assess the needs and capabilities of the potential recipient thereof, and transmit knowledge in a way that allows it to be used in another location of the firm’s organization at home or abroad (Martin & Salomon 2003). The resource interaction in the coupling and matching of internal and external network processes affects knowledge transfer efficiency and, finally, has a vital impact on the firm’s overall business performance (Gadde, Hjelmgren, & Skarp 2012).

A firm’s industry network engagements, initiated in order to better manage resource assets, come along with advantages and also with potential risks. Why? Knowledge and experience serve as the most valuable firm resources. Protection of these resources from imitation by securing intellectual property rights (e.g., patents, copyrights, and trademarks) is of interest but, naturally, has limits. The choice of market entry mode affects the protection of strategic knowledge. For example, a wholly owned subsidiary provides better prerequisites for knowledge safekeeping than an international joint venture (Martin & Salomon 2003). Why? In a joint venture, knowledge is necessarily shared with the partner firm (e.g., value-adding process know-how). Consequently, through the process of learning and imitating, the joint venture partner firm may eventually become a competitor. Protection of intellectual property is always a challenge, and the key is to be faster than the competition if a leading technology firm wants to keep its competitors at bay. Innovators with advanced technological and managerial knowledge resources have to adapt their market entry concepts carefully and intelligently and should think twice when deciding with whom in the market to form a long-term partnership, such as an international joint venture (Teece 2000).

Mathews (2002) analyzed international activities, examining the cases of incumbents (firms that are already established in the worldwide market) and international latecomers (those with delayed global market entry) as examples based on the RBV. Latecomers are firms that delay their global market entry relative to the majority of their competitors. They use the benefits of their network relationships, which are a valuable resource and help them overcome market entry barriers such as limited knowledge about international markets, suppliers, and customers (Mathews, Hu, & Wu 2011). Learning from network partners allows a rapid substitution for less developed inner resources and experience; thus, international latecomers and/or small and medium-sized firms can leverage advantages from the incumbents, for example, through long-term partnerships. Within the global economy, international latecomers can more readily build their global operations by linking up with existing players than was possible in the past (Mathews 2002).

1.2. Resources and Dynamic Capabilities

Innovative firms that successfully act in the global arena usually exhibit dynamic capabilities to gain, reconfigure and integrate external and internal resources in order to match current market expectations and also to create market changes for the future (Liao, Kickul, & Ma 2009). Dynamic capabilities reflect a firm’s capacity to deploy resources through developing, carrying, and exchanging information, which leads to specific and identifiable processes concerning product development, international market entry, and relationship building (Lin, McDonough III, Lin, & Lin 2012). Particularly in web-based service industries, imperfectly imitable capabilities (e.g., innovative ideas) become more important as a source of competitive advantage than conventional asset resources, such as real estate, land and others (Erramilli, Agarwal, & Dev 2002). In stable markets where changes are predictable, dynamic capabilities rely on existing knowledge, and the learning process is limited to organizing and assembling resources as a consequence of market changes. However, because of liberalized global trade patterns, international markets have become more complex and, as a consequence, less predictable. Based on the RBV grounding, Teece et al. (1997) highlight a firm’s ability to achieve new forms of competitive advantage, necessary in turbulent and uncertain markets, as dynamic capabilities and mention two key aspects related to this.

- First, the term ‘dynamic’ refers to the capacity to renew competencies so as to achieve congruence with the changing business environment. Certain innovative responses are required when time-to-market decisions are crucial, the rate of technological change is rapid, and the nature of future competition and markets is difficult to determine. All these elements are valid in order to characterize the high-technology industries and their competitive market environments.

- Second, the term ‘capabilities’ emphasizes the key role of strategic management in appropriately adapting, integrating, and reconfiguring internal and external organizational skills, resources, and functional competencies to match the requirements of a changing environment. Capability is a special type of an organizationally embedded nontransferable firm-specific resource, whose purpose is to improve the productivity of the other resources possessed by the firm (Makadok 2001; Teece et al. 1997).

Successful players in the global marketplace are firms that can demonstrate timely responsiveness and rapid and flexible product innovation coupled with the management’s capability to effectively coordinate and redeploy internal and external competencies. Management activity cannot lead to the immediate replication of unique organizational skills through simply entering a market and piecing the parts together overnight. Replication takes time, and the replication of best practices always may be illusive. The potentials for firm capabilities are understood in terms of organization structures and managerial processes that support productive activity (Teece et al. 1997). Dynamic markets force firms to react, within the shortest possible time period, to changing business situations and so to renew competencies in order to respond innovatively in the market (Eisenhardt & Martin 2000; Zuchella & Scabini 2007).

1.3. The Approach ofJohanson and Mattsson

Beginning in the mid-1980s, among the first to focus attention on network dynamics in the internationalization of business were Johanson and Mattsson (1985, 1988,1992). They claimed that firms are embedded in industrial networks and linked to each other through long-lasting relationships that develop complex interfirm information channels. As a result, the industrial system is composed of firms engaged in supply, production, distribution and service. The authors describe this system as a network of relationships among the firms (Johanson & Mattsson 1988).

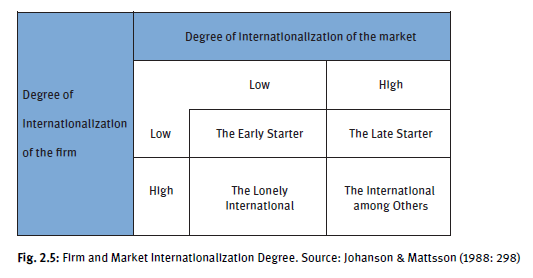

A firm’s internationalization development is to an important extent dependent on its position in the network. Thus, the internationalization characteristics of both the firm and the market influence the process. The firm’s market entry resources have different structures if the firm is highly internationalized (e.g., foreign market experience) in relationships than if it is less or not experienced at all. Furthermore, the market assets of other firms in the network have a different structure depending on whether the market has a high or low degree of internationalization. From this assumption, Johanson and Mattsson (1988) identify four categories that determine the degree of market internationalization in relation to the degree of firm internationalization. These categories are illustrated in Figure 2.5.

The early starter describes firms with few relationships with other enterprises abroad. Competitors, suppliers, and other firms in the domestic as well as in foreign markets have few but important international relationships. The initiative to start foreign operations comes from other parties, such as distributors or important customers located abroad.

The lonely international is a firm that is highly internationalized, while its market environment is not. The company has unique knowledge of cultures and institutions abroad developed through relationships in foreign markets. The firm’s advanced international expertise compared to other firms gives it a favorable position with easier access to international networks. Initiatives for further internationalization are not developed by other parties in the network since the firm’s suppliers, customers, and competitors are not internationalized. The lonely international has the qualifications and resources to promote internationalization for the firms that are engaged in the network. To exploit the advantages of being a ‘lonely international,’ the firm has to coordinate activities in the different national networks, which necessarily requires international integration knowledge (Johanson & Mattsson 1988).

The late starter describes a firm focused on the home market and forced to internationalize by other players, such as customers or suppliers that are actively involved in international business (e.g., the follow-the- customer phenomenon). Comparative disadvantages for the late starter come from having less international experience. But because it is embedded in the network, the late-coming firm is able to gain access to the knowledge and international experience of other firms (Johanson & Mattsson 1988). The descriptions of a late starter are in accordance with Matthews’ international latecomer phenomenon and its derived advantages and disadvantages for the firm in the global business arena (Mathews 2002).

The fourth category is the international among others. In this case, both the firm and its environment are highly internationalized. Market expansion and penetration of an international firm takes place in global networks. The advantage for this firm is that it is able to coordinate operations in international networks in order to react to changes in the market environments. Disadvantages derive from an increased communication and coordination complexity on a global scale. The international among others predominantly faces counterparts and competitors who are themselves internationally active in markets that are rather tightly structured. Major positional changes in the network will increasingly take place through mergers and acquisitions, as well as joint ventures, in contrast to the situations of firms in the previously introduced categories (Johanson & Mattsson 1988).

Johanson and Mattsson (1988) claim that the network approach can distinguish entry strategies that differ with regard to the characteristics and number of relationships the entry firm seeks to establish with other firms in the network. It can be expected that because of the cumulative nature of network processes, the sequential order of activities in international markets is important and should be given more attention in research. From the strategic point of the most interesting research issue is derived the analysis of how to get prepared for international market entry and penetration when the time is ripe. Following the idea of the network concept, preparedness for, and the successful implementation of, international market entry strategies is largely a matter of having relationships with other firms and institutions embedded in the network.

1.4. The Concept of Johanson and Vahlne

An increasing market dynamism linked with the rapid internationalization processes of firms, witnessed during recent decades, has led Johanson and Vahlne to review their own concept of psychic distance and conclude that ‘we have a situation where old models of internationalization processes are still applied quite fruitfully at the same time as a number of studies have suggested that there is a need for new and network- based models of internationalization. We think it might be worthwhile to reconcile and even integrate the two approaches’ (Johanson & Vahlne 2003:84). As a result, Johanson and Vahlne have further developed their Uppsala internationalization model of incremental market entry towards an integrated business network model for internationalization. They define business networks as sets of interconnected business relationships, in which each exchange relation is between firms and is conceptualized as collective steps. According to this definition, all firms are engaged in a limited set of business relationships with customers, suppliers and service providing firms (e.g., logistics, finance and banking) that, in turn, have relationships with other firms (Johanson & Vahlne 2003).

Hohenthal (2001) claims that there is always a connection of two separate pools of knowledge when a new relationship between actors is created. Through this connection, the firms gain access to each other’s knowledge systems (and their international experience), which can be used in other relationships and in the creation of new international business opportunities with less cost than would be required to generate the knowledge by themselves. International experience gives the firm an ability to see and evaluate global business opportunities and thereby reduce the uncertainty associated with commitments to foreign markets. Accumulated knowledge and experience in foreign markets leads to improved overall international business performance (Lou & Peng 1999).

Johanson and Vahlne (2003) distinguish between market-specific experience and operation experience. The former concerns conditions in the particular market and cannot, without great difficulty, be transferred to other markets. The latter refers to ways of organizing and developing international business operations that can more easily be transferred from market to market. Apparently, the internationalization of a firm is associated with commitment decisions such as cooperative agreements with suppliers, distributors or customers; acquisitions of competitors; or direct investment in operations and manufacturing abroad. The more specific and the more integrated those activities abroad, the stronger is the firm’s dependence on them and, as a consequence, the higher the corresponding market exit barriers (Johanson & Vahlne 2003). Within a business network perspective, market entry difficulties are not mainly associated with the general market surroundings in a country. The challenge is rather in terms of specific customer or supplier firms’ characteristics due to language, ethics, and cultural obstacles, such as different perspectives on avoiding business uncertainty and short- versus long-term business performance views (Hofstede 2001; Johanson & Vahlne 2003).

Consequently, Johanson and Vahlne (2003) combine the incremental internationalization process and the network models, assuming there is one set of business-related managerial issues that is relationship-specific and another set of challenges associated with country-specific institutional and cultural barriers. On the way to internationalization, the enterprise has to overcome these challenges. International expansion is a result of the firm’s establishment of relationships with other industry actors, such as suppliers and customers. Success in international business significantly depends on the company’s ability to build a network, which, for its part, depends on the firm’s learning openness and experience in developing it. Subsequent foreign entries benefit from the learning and experience gained from previous operations. Experienced managers who are familiar with international business help the company overcome difficulties related to entry activities in new markets (Li 1995). Johanson and Vahlne (2003) distinguish between three types of network learning, which acquire extraordinary importance with regard to prosperous internationalization activities.

Three types of network learning

First, firms do business in customer-supplier relationships. They learn partner-specific behaviors, such as willingness and ability to maintain and develop the relationship (e.g., order forecasting reliability, flexibility, and keeping promises related to the business). As a result, they learn about each other and how to coordinate their activities in ways that strengthen their joint business. Such connection increases the firms’ commitment in the foreign market.

Second, experience in relationship development assumes that when interacting in business engagements, the involved partner is learning skills that may be transferred to and used in other business transactions. These skills include how to get in touch with new business network actors (e.g., customers and suppliers) as well as expertise on knowing how to develop and deepen relationships with them.

Third, coordinating experience concerns several supplier relationships, for example concerning new product developments or just-in-time delivery schedules. It also concerns coordination between a supplier and a customer in order to make both parties’ value chain activities more efficient. All of these connect and intensify the relationships of the business network (Johanson & Vahlne 2003).

International business experience is not the result of positive international business outcomes only. Negative experiences gained from a firm’s failure concerning its foreign market entry are also of significant value for the management and develop the entire internationalization competence of a firm. Experience, whether negative or positive, thus seems to be important in the triggering, creation and development of the international market entry processes (Hohenthal 2001).

As a consequence of relationship learning, the firm acquires expertise on how to build new business relationships and how to connect them to each other. The relationship development experience is likely to be useful also when the enterprise approaches strategic relationships (Johanson and Vahlne 2003). For instance, joint ventures may be made in order to secure technological resources or to gain the strategic advantage of the cooperating partners through shared distribution channels relative to their competitors. Foreign market expansion is, first, a matter of developing the firm’s relationships in a specific market; second, establishing and developing supporting relationships (e.g., local politicians and government); and third, cultivating connections that are similar or connected to the focal one. In order to support a strategic relationship with a partner, the firm might be forced to develop a relationship in another country, thereby entering that foreign market (Johanson & Vahlne 2003).

Mathews (2002) similarly argues that firms possess a unique set of relationships that contribute to their own resources and capabilities. An enterprise is able to improve or enhance its capabilities by attracting and sharing resources with other firms with which it shares connections. A network perspective of the economy and its players, which can accommodate the perspectives of firms developing complementary strategies and accessing more mobile resources, needs to be contrasted with the conventional view that sees enterprises as atomistic entities engaged in arm’s length transactions with each other, mediated through the price system.

Those firms are viewed only as production entities with transparent technology in the form of a production function that converts input and output. However, markets have become increasingly integrated (e.g., software and hardware electronics in cars), industries have become digitalized, and value-added activities are more complex. Therefore, the conventional view of a (manufacturing) firm and its internationalization processes needs to be replaced with an interdisciplinary perspective and the firm’s location in networks.

The creation of knowledge through technological learning is crucial to gaining a competitive advantage in international business. Interactions with reliable business partners provide important insight into other firms’ research and how those products develop over time in the international markets. The functions and the design of products and services used to meet local customer expectations can be more easily observed through interlinks with foreign business partners. Thus, the development of future products and services can be adapted to better meet local market conditions. The main characteristic of those interlinked firms is their engagement in a global ‘lattice’ construction, with accelerated global expansion as the key goal. Firms that develop a corporate culture and organizational structures that ensure the effective integration of technological and administrative learning from their international interfaces will boost their performance in international business (Zahra 2005; Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt 2000). As a result, the resource-based view turns out to be a suitable ground for understanding the dynamics of international competition. Seeing the emerging global economy as networks of interlinked enterprises provides a fresh perspective on the process of internationalization (Mathews 2002; Sharma & Blomstermo 2003).

Vahlne and Johanson (2017:9) affirm that ‘what happens in a firm happens in relationships.’ A global ‘market’ for exchanges, comprising social and economic transactions, is amplified and hybridized through modern technologies and ongoing digitalization, with which intangible and tangible elements are traded. Through a convergent shift in technologies, organizations, and geographies, we see a new underlying reality of international business (IB): the rise of knowledge connectivity in innovation systems. There is a need to further explore the nature of the connections that span geographic, organizational and technological space (Cano-Kollmann et al. 2016). In place of discussions of ‘one-off’ knowledge transfer or development, the new agenda consequently necessitates continuous two-way interactions in knowledge development (Vahlne & Bhatti 2019).

1.5. Review of Inter-Organizational Network Positioning Approach

The network concept draws particular attention to the social and cognitive ties that are formed among actors (e.g., suppliers, customers, service providers, banks, etc.) engaged in international business. The rapid growth of new entrants in the global arena leads to the conclusion that enterprises do not necessarily internationalize incrementally as claimed in the Uppsala approach (Johanson & Vahlne 1977).

Against the background of globalization, international firms make increasing use of their global networks. While traditional foreign-market entry research describes how firms decide on markets and appropriate entry modes on their own, the network approach concentrates on how existing actors influence the entry of new firms into networks that provide the base for business activities abroad (Bjorkman & Forsgren 2000).

Firms maintain a range of bilateral relationships, and researchers who favor the network approach need to include a variety of variables in their analysis. Thus, the measurement and evaluation of a firm’s business performance within the context of international relationships and their individual impact on the firm’s performance in terms of its foreign market entry success are methodologically enormously complex and are, therefore, challenging (Samiee & Walters 2006). Further conceptual difficulties are measuring the ownership control and the efficiency and effectiveness of bilateral relationships in networks (Jones & Coviello 2002).

Network research tends to focus on the actor’s behavior in oligopolistic business-to-business market surroundings (Dunning 1995a). The resource dependence theory, which is derived from the resource-based view, emphasizes resource exchanges, such as in international joint ventures, as the central feature of these relationships (Newbert 2007). According to this perspective, groups and organizations gain power over each other by controlling valued resources. In parallel, there is always the risk of opportunistic behavior from the participating players in the industry network. This causes network instabilities as a considerable number of firms involved in joint ventures experience failures, much to their regret (Das & Teng 2000; Glaister, Husan, & Buckley 2003; Schuler 2001). While descriptions of individual examples through case studies of business reality are often satisfactory, the corresponding research results are hard to generalize and future predictions tend to be vague. Consequently, the theoretical potential of drawing conclusions about common patterns of internationalization in global networks is challenging and requires intensive and costly research (Bjorkman & Forsgren 2000).

Since the 1990s, the network approach of internationalization has been amplified. Innovative, young, and usually small firms often start their foreign business early in their establishment. Therefore, the phenomenon of rapid and not necessarily gradual internationalization processes has entered the academic literature. The appearance of these types of firms and the influence of their ‘entrepreneurs’ have led to a second stream of the network approach that specifically focuses on social ties of bilateral personal relationships in terms of the firm’s international market entry strategies.

2. Interpersonal Relationships Approach

2.1. Early Internationalization of the Firm

The digitalization of various industries, e-commerce, improved and faster logistics, and liberalized trade patterns has permanently fostered new business opportunities for smaller firms with limited conventional resources. The phenomenon of rapid internationalization of relatively young firms has directed the focus of scholarly research to the role and influence of the entrepreneur in the firm’s international activities (Oviatt & Mc Dougall 1994; Shrader, Oviatt, & Mc Dougall 2000).

Firms that are able to internationalize rapidly often have established personal relationships with firms abroad. Consequently, they are intensively embedded in international business structures (Hohenthal 2001). Thus, members of the international network value relationships rather than discrete and contractual, formalized transactions (Coviello & Munro 1997).

How to define an ‘early internationalized

The emergence of digitalized service-based industries in particular has further supported the business opportunities of small and medium-sized enterprises to internationalize rapidly after inception. The changing pattern of internationalization, especially among small firms, has been increasingly discussed in the literature. However, definitions that describe the phenomena of firms that internationalize in the early stages after the firm’s founding are rather heterogeneous than unified in the literature (Lopez, Kundu, & Ciravegna 2009).

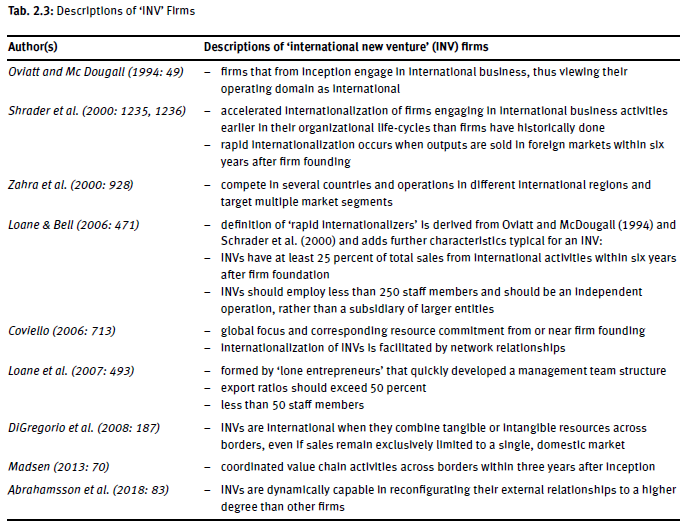

One of the most cited definitions stems from Oviatt and McDougall (Oviatt & Mc Dougall 1994: 49, 94), who describe an international new venture (INV) as a business organization that ‘from inception, seeks to derive significant competitive advantage from the use of resources in the sale of outputs in multiple countries.’ Further INV definitions, to name just a few, are from Zahra et al. (2000), who specify INVs as firms competing in several countries with operations in different international regions and targeting multiple market segments. Coviello (2006) describes INVs as ‘different’ from conception because from near founding, they have a global focus and commit resources to international activities. According to Madsen (2013), INVs coordinate value chain activities across borders within three years of inception. Abrahamsson et al. (2018), claim that INVs are dynamically capable in reconfigurating their external relationships to a higher degree than other firms.

Adding to the complexity is variation in the definitions regarding the time span between the establishment of an INV and its first international sales, as well as how much foreign sales should contribute to total sales. Shrader et al. (2000:1235) describe INVs as firms that start their international activities “within six years after the firm’s formation”. Knight and Cavusgil (1996:12) limit the time span to up to “three years to reach an export sales level of at least 25 percent”. In contrast, Oviatt and McDougall (1997: 86) define a period of “six years” as a standard time span, whereas Rennie (1993: 45-46) claims a period of only “two years with 75 percent of revenues” coming from exports (Glowik & Bruhs 2014). Table 2.3 provides an overview and summarizes INV definitions as currently present in the literature.

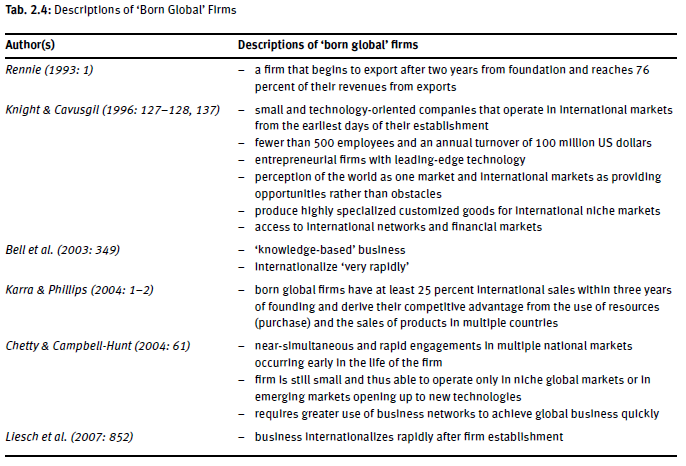

In addition to INVs, another differentiating term emerged in the literature: the ‘born global.’ INVs and born global deal with the same phenomenon: a category of firms that implement their international business from their foundation. They develop their internationalization knowledge through an ‘absorptive capability,’ usually fostered and developed by their entrepreneurs, who use their versatile and diversified personal relationship ties in foreign markets. Born global firms are usually found in new technological-based service businesses with a strong customer orientation linked to the utmost flexibility in order to adapt their market entry strategy to the needs of the local market circumstances (Sharma & Blomstermo 2003). Table 2.4 illustrates the most common descriptions of born global firms in the literature.

Grant (1996) emphasizes the role of the individual as the primary actor in knowledge creation and the principal repository of knowledge. According to this logic, a firm’s potentials to immediately launch international business engagements are fostered by the firm’s people, in particular the entrepreneur, who is often, but not always, the founder and business owner (Zahra et al. 2005). Entrepreneurial capabilities may result in finding ways to create value beyond the established competitors and usually conventional, resource-rich industry incumbents. Competitive advantages in the global marketplace are mainly derived from the particular intangible assets of the young and early internationalizing firm (e.g., organizational cultures and personal relationships). Consequently, the success of the firm is influenced by the ability of the entrepreneur to mobilize and dynamically combine external and internal resources and adapt them to changes in the environment. Particularly, personal contacts and social interaction play an extraordinary role when it comes to market entry decisions – especially where complex technological products with a high service value are concerned (Axelsson & Easton 1992; Ellis 2000). Dynamic capabilities allow a flexible reconfiguration of the firm’s asset structures in terms of product portfolio, process efficiency, and personal and organizational experience (Zuchella & Scabini 2007).

International entrepreneurship has been identified as involving firm activity that crosses national borders. Consequently, it is a combination of innovative, proactive, and risk-seeking behavior intended to create value in organizations (Jones & Coviello 2002; McDougall & Oviatt 2000; Young et al. 2003). McDougall and Oviatt

(2003) enlarged the definition of international entrepreneurship ‘as the discovery, enactment, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities – across national borders – to create future goods and services.’

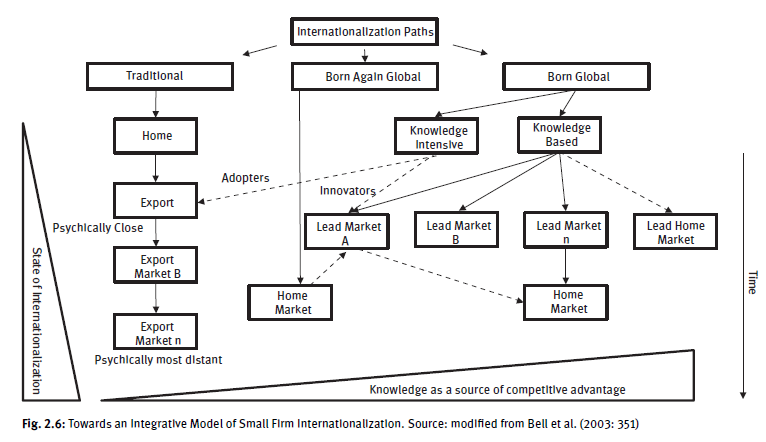

An integrative model comparing traditional and rather large firms versus modern entrepreneurial small business firms and their diversified internationalization processes was developed by Bell at al. (2003) and is illustrated in Figure 2.6. The authors claim that firms can follow different pathways of internationalization. These modes include the traditional, the ‘born global,’ and the ‘born again global’ pathways. The model attempts to explore and seeks to explain any variations in the patterns, pace, and process of internationalization. The authors illustrate contrasting internationalization patterns, including different motivations, aims, strategies, and methods of market entry.

In business reality, internationalization patterns tend to be highly individualistic, situation specific, and unique. Firms with advanced international knowledge tend to launch international business faster and often more efficiently. The internationalization process is significantly dependent on external environmental conditions as well as on a firm’s internal circumstances, including resource availability, behavioral characteristics, and a global vision of the key personnel. Enterprises may pass through periods of rapid internationalization and drawbacks in international business. These periods are influenced by political/legal impacts, the firm’s customers, or other actors in the industry network. The focus of the model by Bell et al. (2003) is on strategic issues with respect to internationalization concepts of small firms. Additionally, the model provides recommendations for strategy formulation and implementation in order to assist the internationalization process.

2.2. The Dimension of Time

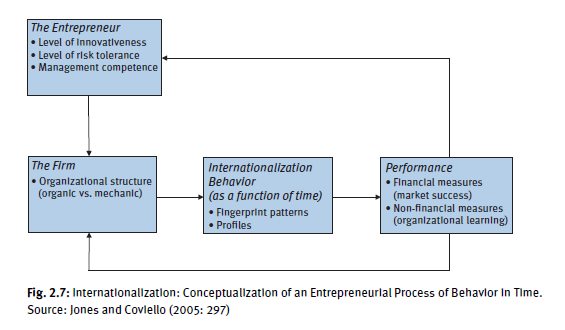

In their model, Jones and Coviello (2005) combine the dimension of time, management’s behavioral aspects, and the influence of the external environment on the firm’s performance. The scholars assume that internationalization is a reflection of time-based behavior, specific to individual entrepreneurs as participants and managers of social systems and networks. Behavioral aspects of the entrepreneur, determined by the decisions and actions that occur at a specific point in time, move to the center of research interest (Jones & Coviello 2002). The relationship between the entrepreneur, the organization, and the external environment is viewed from a systems perspective and assumes the continued activity of input, process motion, output, and feedback over time, whereby elements of the external environment moderate internationalization behavior. The entrepreneurial influence serves to combine resources and knowledge as part of the strategic and tactical activity of the firm (Jones & Coviello 2002, 2004).

Entrepreneurial activities include specific decisions and actions that result in or contribute to internationalization. External associations, such as international business links with other firms abroad and corresponding modes of market entry, are seen as part of that interaction (as indicated on two dimensions, time and country distance). Cross-border activity may commence or terminate at any time, thus leading to a complex pattern of internationalization decisions, processes, and activities. Enterprises with an open, responsive interactivity with the external foreign business community will internationalize more rapidly and successfully than those whose boundaries are relatively impermeable. Consequently, internationalization is a process of behavior that emerges as a firm’s unique response to internal and external influences and is particularly driven by the entrepreneur. Time is a fundamental component of internationalization in that each firm has a history comprised of significant internationalization events occurring at specific points in time. For example, the establishment of a new type of cross-border link, such as the start of an export activity, represents a milestone in the firm’s chronology of internationalization (Jones & Coviello 2002).

The internationalization process is understood as ‘value-creating-events’ (Jones & Coviello 2005). As illustrated in Figure 2.7, the entrepreneur’s level of innovativeness, risk tolerance, and managerial competence has a significant impact on the firm and its organizational structure. The firm’s internationalization behavior is a result of ‘fingerprint pattern’ and profiles over a period of time. The ‘fingerprint’ of internationalization behavior includes the functional diversity (decision of entry mode choice) and country diversity (geographic, economic, and cultural distance) in relation to time. ‘Fingerprint’ patterns give a static impression at a specific point in time, whereas profiles identify changes over a period of time. Thus, the firm’s internationalization process (e.g., market entry organization) mirrors the entrepreneurial behavior and the firm’s organization (organic vs. mechanistic). Internationalization can be seen as a firm-level entrepreneurial behavior manifested by events and outcomes in relation to time. Internationalization behavior influences the firm’s performance expressed in financial data (profit or loss as indicators of market success) or non-financial assets (degree of organizational learning). Different ‘fingerprint’ patterns of internationalization behavior evolve over time, and firm performance will impact future behavior through an iterative process of further organizational learning.

Reuber and Fischer (1999:31) build on the relationship of time and the ‘stock of experience,’ which influence the international new venture’s performance. Experience includes things that happen or events that occur during a specific time period. A particular event can have both a positive and negative impact on the international business of the firm. For instance, the loss of a key customer might reduce the sales revenue in the short term. This loss may result in better long-term performance if the firm is able to learn from its experience, for example through improvement of product quality or service.

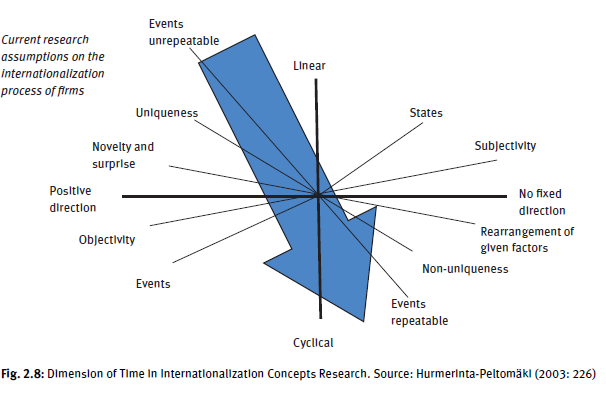

Hurmerinta-Peltomaki (2003) claims that traditional internationalization models describe a firm’s export activities as a linear and predictable pattern on a simple, orderly, or progressive path, which is often an unrealistic notion. Consideration should be given to the idea that particular events or experiences in the past may cause a firm’s reorientation, moving the foreign trade activities in a negative direction and causing export involvement to decrease or even to be interrupted.

Thus, experience over a period of time may cause strategic reorientation that alters or stops the international activities of the firm. Time enables us to understand various organizational processes, in particular those of decision making and learning from positive and negative business episodes. During decision making, the owner or manager intentionally attempts, in the present, to connect the past to the future by assessing the relevance of his/her experience to the future. Experience is the antecedent of present and future activities, and it is this property that makes it relevant and interesting (Butler 1995; Reuber & Fischer 1999).

The past experience dimension, on both the organizational (enterprise) and the individual (entrepreneur) level should be taken into account when describing a firm’s internationalization process. Thus, cyclical, experience-based internationalization on an individual level affects internationalization on an organizational level. Cyclical internationalization may also be perceived on an organizational level in a forward-backward- forward movement. For example, the enterprise is able to utilize its past export experience to continue the internationalization process at present and in the future (Hurmerinta-Peltomaki 2003).

The dimensions of time in international business have not been emphasized adequately in conventional concepts of internationalization so far. As illustrated in Figure 2.8, the direction of development in research on the internationalization process evidently proceeds from the upper left-hand corner (positive direction-linear) towards the lower right-hand corner (no fixed direction-cyclical) (Hurmerinta-Peltomaki 2003).

Traditional research on internationalization is mostly based on a linear idea of time; that is, the models consist of several identifiable and distinct successive stages. A higher stage of international activities indicates a greater foreign involvement (Leonidou & Katsikeas 1996). The challenge in this context is to understand internationalization as a process that is highly dynamic and time dependent. However, paradoxically almost all internationalization models are static in nature; for example, models fail to conceive each export stage as a continuum of episodes and micro-steps (Leonidou & Katsikeas 1996). This is one explanation as to why ‘stages models’ on internationalization are commonly used because permanent changes between the stages are difficult to perceive by researchers. It could be said that two dimensions of time are relevant to the development of internationalization concepts: linear, which describes the human understanding of time as a forward-going line in a positive direction (past-present-future), and cyclical time, which reflects the business reality, but where there is no fixed direction or arrow. This allows for the description of a backward direction of internationalization (Hurmerinta-Peltomaki 2003).

2.3. Towards a Conceptualized Model Typology of International New Ventures and Born Global Firms

Due to a lack of previous or fixed routines in entering foreign markets, international new ventures (or the synonym, born globals) combine their conventional resource disadvantages with the potentials of other actors through personal relationships usually fostered and developed by the entrepreneur (Sharma & Blom- stermo 2003).

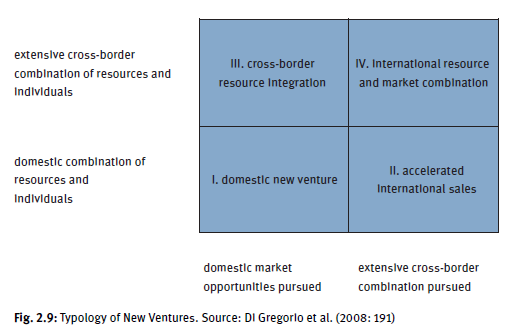

DiGregorio et al. (2008: 190) emphasize the concept of entrepreneurship ‘as the nexus of individuals and opportunities’ applied to international new ventures by distinguishing between opportunities that entail novel resource combinations versus opportunities that entail novel market combinations. The first category of opportunities essentially generates potential for creating value by combining internationally dispersed resources. The latter category of opportunities entails leveraging existing resources into new markets. Resource combination chances refer to the potential to create value via innovative arrangements of international strategic factors. Such factors may include assets that are confined to certain geographic locations, for example access to natural resources, labor force qualifications, and consciousness of the customers and employees. Resource combinations may also involve cross-border pooling of innovative entrepreneurial talent and corresponding knowledge, and/or access to important markets. Market combinations, on the other hand, entail introducing a particular product or service from one country into one or more other countries. Introducing this new perspective enables the delineation of two distinct phenomena: first, the creation of international ventures and second, the process of internationalization of recently established ventures. DiGregorio et al. (2008) categorizes firms into four typologies (compare Figure 2.9).

Quadrant I – Domestic New Venture

The first quadrant contains new venture firms that have a strictly domestic orientation. That means no international sales or resource combination occurs. Such firms cannot be defined as an international new venture but, instead, are a domestic joint venture.

Quadrant II – Accelerated International Sales

International new venture firms categorized in this segment begin international sales at an early stage but do not combine resources across borders. These firms concentrate their resources locally and are typically founded in response to local opportunities. They rapidly expand their market scope to include international markets in order to take advantage of their domestically based resources to exploit differences between local and foreign markets in terms of quality or cost.

Quadrant III – Cross-Border Resource Integration

International new venture firms take advantage of geographically dispersed resources and the diverse knowledge embedded within those resources. The combination of resources across national borders is the main basis for gaining competitive advantage. Because they are embedded in international networks, their opportunities to improve the product quality, service, innovation potentials, or cost structures are enhanced. Existing business models in one market are transferred into another.

Quadrant IV – International Resource and Market Combination

Firms located in this segment depend on cross-border interactions for their tangible and intangible resources in order to realize market opportunities. Competitive advantage is developed by careful management of the risks associated with multiple entries into foreign markets. For these firms, internationalization is a means of creating new value via cross-border resource combination and capturing existing value via international sales (DiGregorio et al. 2008).

International new ventures emerge when resources abroad are combined without necessarily coordinating value chain activities internationally as witnessed for multinational enterprises. For example, an international new venture is created by combining a resource such as technology or a business model from one country with resources and/or markets in another country. International new ventures arise from leveraging domestic resources into foreign markets or to exploit new foreign resource combinations. While Oviatt and McDougall (1994) focus on internationalization soon after a firm’s inception, the concept of Di Gregorio et al. (2008) concentrates on the emergence process of an international new venture. The importance concerning external opportunities of foreign resources (e.g., material procurement, knowledge, and technology transfer), which help to improve the firm’s performance in domestic and foreign markets, has been ignored so far. Entrepreneurs of young firms seeking to internationalize should intensively and permanently search for foreign resource opportunities.

Gabrielsson et al. (2008) propose a born global firm definition that includes various aspects. A firm should have a global market potential and entrepreneurial competence that enables rapid internationalization. Furthermore, a firm should have a distinct differentiation strategy and products with unique technology, superior design, unique service know-how, or other highly specialized competencies. Born globals understand foreign markets as a chance to explore and create new knowledge regarding products with global market potentials. The establishment of a successful start-up firm needs a global vision linked with reasonable risk awareness.

The time factor should be regarded along with two dimensions: precocity (early internationalization) and speed (effectiveness). All-in-all, these types of firms show a broad entrepreneurial scope, high intensity in their business focus, and rapid growth (Gabrielsson et al. 2008; Kuemmerle 2002).

In order to overcome the conceptualization weakness of the entrepreneurial models, Gabrielsson et al. (2008) attempt to develop a combined approach that includes the born global phenomenon and its behavior over time. They describe the firm’s development in different stages and the reasons it proceeds as it does. As a result, the evolution process is divided into three phases: first, the introduction and initial launch phase; second, growth and resource accumulation; and third, the break-out and desired strategies phase.

The first phase, the introduction, describes the period when born globals have limited resources and an undeveloped organizational structure. They rely on unique and mostly tacit knowledge to achieve competitive advantage. The most important resources are the firm founder(s) and other employee resource (knowledge) capabilities and inimitable skills. Combined with entrepreneurship, these abilities may lead to the development of products with global market potential. Firm growth mostly depends on the distribution channel strategy and the relationships chosen – for example, a long-term sales contract concluded with a multinational enterprise and further relationships created through personal relationships of the entrepreneur. Organizational learning is important for the success of the born global, especially knowledge about foreign markets (Gabrielsson et al. 2008).

Phase two describes growth and resource accumulation. Business success depends on the product and service itself and the ability to place it on the market. Knowledge rests on the ability to learn from partners, suppliers, and customers, as well as collected success and failure experiences (Gabrielsson et al. 2008).

Phase three, the break-out and desired strategies phase, describes the period where the born global decides on a strategy based on its previous learning and experience in order to arrange its own position in the markets and its industry network. The strategic reorientation is influenced by the desire for independence from global players and the control of its own actions. A fundamental global vision and devotion are necessary as well as the availability of a client portfolio, which allows the development of international success to continue. At this stage, a born global may develop and continuously grow to become a ‘normal multinational enterprise’ in the future (Gabrielsson et al. 2008).

2.4. The Phenomenon of the ‘Born Again Global’

The limited focus on the start-up phase of new venture firms led (Bell et al. 2003) to an expansion of the discussion of the ‘born again global’ phenomenon. This term describes firms that have become well established in their domestic market with apparently no great motivation to internationalize, but which have suddenly embraced rapid and dedicated internationalization. Born again global firms fail to conform to the conventional stage models of small firms’ internationalization process concepts, which concentrate on the initial phase from the firm’s inception.

The radical change in internationalization behavior of the born again global firm may be triggered by a critical incident or several events happening at the same time. These incidents may include a change of ownership or management, a decision to follow a main customer to foreign markets, or the introduction of internet- based distribution channels. Especially a change of ownership or management has a significant influence on the internationalization path of born again global firms. Not only top management representatives with an international vision, but also other human resources of the firm with special international expertise (for example, embedded in the firm’s sales or purchasing department) influence the company’s internationalization re-launch. Furthermore, additional financial resources and new opportunities may come up due to access to new international industry networks and, consequently, more amplified knowledge (Bell et al. 2003).

The motivation of born again global firms to internationalize is, in comparison to born globals, rather reactive; they only respond to a critical event. Business goals of born again global firms include the utilization of new industry relationships and corresponding emerging resources. Born again global firms show, after the initial reactive event, a more systematic and structured approach to internationalization than born global (international new venture) firms. They also tend to originate from traditional industries rather than from high technology and service sectors. It might be assumed that born again global firms have a better position from which to finance rapid internationalization because they have secure revenues from their home market. These firms have a certain stock of financial resources and knowledge from the ‘critical incident’ at their disposal. However, international business success will not become reality if the firm faces difficulties in the domestic market (Bell et al. 2003).

The born again global concept may also apply well to service intensive organizations because these firms will remain in the domestic market until the business idea and the service quality has been verified as successful and able to be culturally adapted abroad. Another explanation of the born again global firm phenomenon is that these firms initially tried to internationalize but failed. Thus, they decided to build up a supporting domestic infrastructure that would allow them to internationalize quickly and successfully at a later time (Bell et al. 2003; Gabrielsson et al. 2008). An entrepreneurial person may also be able to bring organizational change and innovation to established enterprises. These changes in strategies and knowledge may enable the corporation to form new capabilities and sources of innovation and creativity. Two different approaches derive from this: first, ‘corporate entrepreneurship’ and second, ‘dispersed corporate entrepreneurship,’ also known as ‘intrapreneurship’ (Zuchella & Scabini 2007). These approaches will be introduced in the following chapter.

2.5. Individual and Corporate International Entrepreneurship

When born global firms have grown successfully over time and thus have become mature and carry out various cross-border activities, the variability of the term ‘entrepreneurship’ is increased. Corporate entrepreneurship is characterized by a new division in an established company that identifies and develops new business opportunities for the firm. The department or division acts autonomously, has a relatively flat hierarchical structure, but has strong internal integration with high availability of resources and support from management. In contrast to this, the term dispersed corporate entrepreneurship (intrapreneurship) assumes that every employee has the potential to behave in an entrepreneurial way. Thus, entrepreneurial groups are formed and deal with normal managerial tasks. This entrepreneurial culture within the company culture serves as a basis for any activity, including among others the firm’s internationalization movements (Zuchella & Scabini 2007). The phenomenon of rapid internationalization is often a result of a firm’s internal projects carried out by team members with an entrepreneurial and international spirit (‘international intrapreneurship’) (Cavus- gil & Knight 2015).

There are several ways that entrepreneurial activities can take place either inside or outside of a firm. Developing them inside the firm would involve organizational structures and managerial capabilities. Outside development would include another business stakeholder – for example, long-term contractual relationships with a supplying firm. Entrepreneurial activities increasingly become the focus of international subsidiaries of mature and rather large enterprises. These subsidiaries are controlled by the firm’s headquarters but act proactively and find new resources and chances to expand their business. Over time, they develop their own unique capabilities and personal bilateral relationships. The local environment makes local managers alert to new opportunities and creates an entrepreneurial orientation within the subsidiary. As a result, the local subsidiaries act independently for the most part in pursuing opportunities and develop an organizational culture that sets particular international goals and strategic directions. This development of entrepreneurial subsidiaries can be seen in connection with the need for local market responsiveness. To what extent the subsidiary can determine independent actions, roles, and objectives, or whether these issues have to be strictly in accordance with the goals of the headquarters seems to be important. The self-determined and autonomous approach facilitates local entrepreneurship. It ensures exposure to different resources, local knowledge, and close contact with markets and their customers. Entrepreneurial subsidiaries allow further development of adapted solutions and more effective management in the course of the firm’s internationalization process (Zuchella & Scabini 2007).

If the role of the firm’s international subsidiary is more independent and innovative, it develops and implements better performing strategies because it is closer to the local markets. Moreover, this role supports the employee’s motivation to be innovative and entrepreneurial in the future. It can be assumed that turbulent, complex, and dynamic environments better foster entrepreneurship due to the pressure for the firm to be competitive through permanent innovation and improvement. Nevertheless, there is still a need for coordination and integration of companies in order to avoid duplication of efforts. The multinational firm needs to monitor and evaluate the subsidiary in strategic and financial terms, which cannot be done without managerial and organization efforts that entail corresponding costs (Zuchella & Scabini 2007).

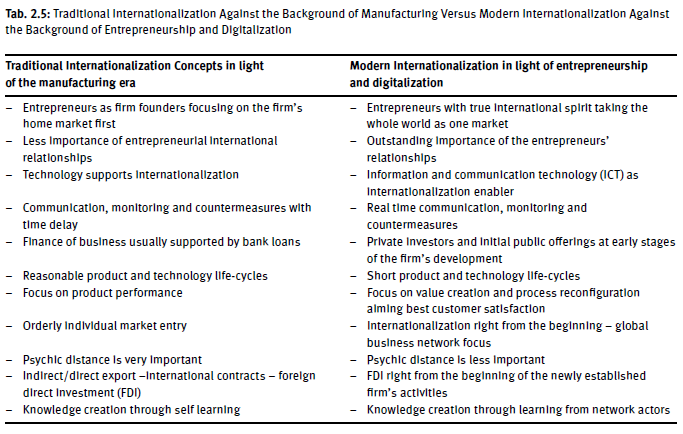

2.6. Review of the International New Venture, Born Global, and Entrepreneurial Concepts

Entrepreneurship and its impact on a firm’s internationalization concepts are upcoming research topics particularly in light of digitalization and corresponding new technology-driven business concepts. The different contributions in this field have their roots in many disciplines (e.g., business administration and social sciences, psychology), but generally accepted definitions and unified theoretical frameworks are still missing (Holmquist 2003; Zuchella & Scabini 2007). Despite the lack of a uniform model, the international start-up phenomena has contributed significantly to a changing perspective of modern internationalization strategies against traditional internationalization concepts. Major differences between traditional firm internationalization versus modern internationalization are summarized in Table 2.5.

Digitalization serves as a transformation process which includes not only operations, but the company’s value propositions and its internationalization path – the move form product- towards process-oriented. Tech-driven service start-ups, in particular, make use of new business opportunities which are possible through digitalization. Relationships fostered by the founding entrepreneur serve as a vital facilitator for implementing a young firm’s digital business concepts (Coviello et al. 2017). Success in international business is dependent upon the embedding of the entrepreneur in cross-border institutional structures comprising national and international networks (Young et al. 2003). In addition to the role and influence of the entrepreneur, international new venture models take into account various other influential factors (e.g., the

factor of time, internationalization processes, and internal and external environmental surroundings of the firm). The weight of a single businessperson or entrepreneur when making internationalization decisions seems significant in start-ups and/or small and medium-sized companies. This influence is, however, rather restricted or even legally restrained in larger or multinational companies. The impact of the owner on internationalization decisions is fundamentally stronger in hierarchical cultures with a relatively high degree of top-down decision power than in less hierarchical firm cultures.

Rialp-Criado et al. (2002) critically mention diversified denominations such as international new venture, born global, instant international, and so forth, which describe the same phenomenon of internationalization but increase the confusion and complexity of the theoretical concept. They further argue that the term ‘global’ is too ‘optimistic’ to be suitable for most firms and their degree of international scope. Therefore, the authors recommend using the term ‘international new venture.’ In the corresponding literature, there are variations in the definitions regarding the time span until an international new venture records the first international sales after its establishment and how much this contributes to the total sales.

Therefore, confusion arises because there are no fixed definitions of the time span concerning the initiation of international business after the firm’s establishment and the extent of foreign business in order to arrive at a common basis for empirical research.

Entrepreneurs take considerable risks when they pursue opportunities in international markets. Differences in international business performance among firms arise because of the creativity and modes of exploitation the entrepreneurs might use. Entrepreneurs are also embedded in a social context and in institutional external environments and experience with success and failure influence their internationalization behavior (Zahra et al. 2005).

Loane et al. (2007) argue that entrepreneurship research tends to focus on the owner or key decision maker. In light of project team structures, particularly in knowledge-based industries, this approach needs to be reconsidered. Team members as a collective may have more experience in a greater number of international markets, and their combined networks of contacts are likely to be more extensive than those of a single founder. Rapidly internationalizing small and medium-sized firms are often founded by teams that have more diverse skills and wider personal network relationships (Cooper & Dailly 1997; Loane, Bell, & Cunningham 2014). Similarly, Zuchella and Scabini (2007) recommend that the role of individuals, as well as organizations, has to be analyzed in conjunction with their relationship networks.

A firm-specific transformational process, sometimes provoked spontaneously due to severe market or technology changes, causes new organizational structures (Van de Ven & Poole 1995).

However, testing and measuring of entrepreneurial activity in international new ventures, and time-based approaches tends to be difficult due to the difficulty of generating quantifiable data. For example, it is hard to verify whether a particular time event (e.g., meeting with visitors who passed the firm’s booth at the trade fair by chance and later became international customers) causes changes or routes the international business activities of the firm in a particular direction. Thus, empirical methodology and a structured, dominant theoretical framework are missing in the current literature.

Source: Glowik Mario (2020), Market entry strategies: Internationalization theories, concepts and cases, De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 3rd edition.

You should take part in a contest for one of the best blogs on the web. I will recommend this site!