1. Incremental Market Entry Through Accumulated Knowledge

During the mid-1960s, Carlson, one of the pioneers of internationalization process theories, argued that firms pass cultural barriers when entering foreign markets. With increasing experience in foreign operations, the enterprise is willing to enter one market after another (Carlson 1966). Firms handle the risk problem through an incremental decision-making process, where information acquired in one phase is used in the next phase to take further steps. Through this incremental behavior, the organization can maintain control over its foreign activities and gradually build up its knowledge of how to conduct business in diversified foreign markets (Carlson 1966; Forsgren 2002).

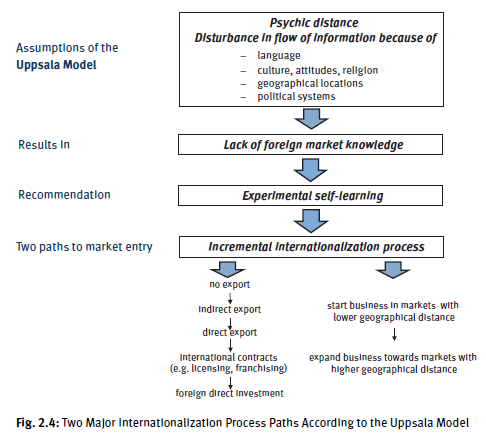

Based on the empirical observations of Swedish pharmaceutical, car, steel, pulp, and paper firms, Johanson and Vahlne (1977,1990) further developed the ideas of Carlson and introduced the gradual internationalization theory. Their research results, in connection with articles from other scholars at the University of Uppsala concerning the internationalization processes of firms (compare: Carlson 1975; Forsgren & Johanson 1975; Johanson & Wiedersheim 1975), later became known as the ‘Uppsala internationalization model’ (Bjorkman & Forsgren 2000). The Uppsala approach assumes that enterprises, due to a lack of foreign market knowledge, which is connected to corresponding market uncertainty, follow an incremental internationalization chain pattern.

Incremental internationalization pattern

At the start, there is no regular export. Business is concentrated in the home market. Then export begins via independent representatives (agents), later through sales subsidiary, and eventually foreign manufacturing may follow at the end (Johanson & Vahlne 1977)

Lack of knowledge, due to differences between countries with regard to language and culture, is an important obstacle when making decisions connected with the development of international business activities. As a consequence, another pattern can be derived: firms prefer entering new markets with lower psychic distance. Psychic distance is defined in terms of factors such as differences in language, culture, political systems, and others that disturb the flow of information between the firm and the market. Thus, firms start internationalization by going to those markets with somewhat lower geographical distance, which they can better understand and where the perceived market uncertainty is relatively low (Johanson & Vahlne 1977,1990).

In their incremental internationalization model, Johanson and Vahlne (1977) distinguish between state aspects (market commitment and market knowledge) and change aspects (current activities and commitment decisions).

- State aspect/market commitment: the degree of commitment is higher the more the resources are integrated and the more their value is derived from these activities. Vertical integration means a higher degree of commitment than a conglomerate foreign investment. An example of resources that cannot easily be directed to another market is a marketing and sales organization with country-specific product modifications and service with highly integrated customer relations. The more specialized the resources are to the specific market, the greater is the degree of commitment.

- State aspect/market knowledge: structure of competition, supplier and customer characteristics, and cultural aspects belong to market-specific knowledge, which can be gained only through experience during operation in the foreign market. Experiential knowledge, which is associated with particular conditions in the market in question, cannot be transferred to other individuals or markets. It can be considered a unique resource. The more valuable the resource for the firm, the stronger is the commitment to the market.

- Change aspect/current business activities: for instance, marketing and sales activities belong to running firm operations. The higher the investments in advertising in a foreign market, the more technologically sophisticated and differentiated the product, the larger the total commitment as a consequence of current activities.

- Change aspect/commitment decisions: enterprise decisions to commit resources (i.e., financial, human workforce, and advertisement) to foreign markets depend on a firm’s general business experience as well as market-specific experience.

Additional commitments are made in small steps unless the firms have a very large amount of resources and/or market conditions are stable and homogeneous or the firm has more of its experience from other markets with similar conditions. Further market experience leads to a stepwise increase in operations and integration with the foreign market environment, thus resulting in a greater market commitment (Johanson & Vahlne 1977).

The internationalization process of a firm has been similarly described by Luostarinen (1980) as a stepwise and orderly utilization of outward-going international business operations (compare Figure 2.4). The incremental and orderly geographical expansion from countries with close business distance to more distant markets causes an increasing dependence on marketing, purchasing, production, finance, human resources, and other functions of the company related to its international markets. Physical distance represents a restricting force to the flow of information and disfavors countries located farther away from the firm’s home base (Luostarinen 1980).

Market uncertainty in international business is usually related to knowledge. Learning is a process of accumulating knowledge either through access to information or business experience. The introduction of the concept of organizational learning represents a dynamic process where firms seek experiential knowledge about individual clients and markets, as well as about institutional factors, such as how to deal with local laws, governments, infrastructure and cultures. Information is accumulated through activities and presence in foreign markets, which increases costs. These costs arise in the process of collecting, encoding, transferring, and decoding knowledge, as well as changing the resource structures, processes, and routines in the

organization. Thus, knowledge plays a crucial role in international strategy decision-making (Eriksson, Jo- hanson, Maikgard, & Sharma 1997; Luostarinen 1980).

Internationalization is a process that is often difficult to plan without avoidance in advance. Organizational structures and routines are built gradually as a consequence of learning: First, a firm’s internal capabilities and competence (e.g., language and business culture qualifications of employees) and second, foreign market requirements (e.g., quality consciousness and service expectations). In this process, understanding the history of the firm is important. Sporadic interaction with actors in foreign markets provides little experience. The more the firm pursues durable and repetitive linkage with external participants abroad, the better the basis for the improvement of internal organizational routines and procedures (Eriksson et al. 1997).

2. Review of the Uppsala model

According to the Uppsala approach, firms internationalize incrementally from physically and culturally close foreign business markets to more distant countries. During the internationalization process, the firm gains experience and knowledge stock that forms the basis for further foreign activities in countries that are located farther away from the home market. The organizational learning process through accumulated experiential knowledge and through ongoing activities is very important for the firm and its successful international business expansion. How the organizations learn and how their learning affects their organizational behavior are crucial elements of the Uppsala concept. The more market knowledge the firm acquires through its own experience, the less is the perceived risk and the higher is the propensity for foreign market entry.

During the last decades, the Uppsala model became one of the most cited, discussed, and criticized models in the international business literature (Barkema & Drogendijk 2007; Hadjikhani 1997). It is claimed that the model is too deterministic because it considers Swedish firms only, and research is grounded on a relatively small number of firm cases. In modern international business, firms are less inclined to repeat the value chain in each country. Instead, firms reconfigure their global value chains accordingly where revenues are high and/or costs are low. The model tends to ignore the fact that a firm also faces a risk by not entering a foreign market – the risk of not participating in an upcoming industry cluster of supplier and customer networks where the firm’s competitors are looking for their chance for business (Forsgren 2002).

The Uppsala model narrowly focuses on ‘knowledge’ and ‘learning’ as major influencing factors for market entry decisions and business performance in the course of the internationalization process (Dunning 2000). In modern business, there is a tendency towards shorter product life-cycles and faster knowledge transfer due to improved communication and information technologies; thus an incremental market entry may mean loosing sales opportunities because competitors may react faster. An incremental and rather slow international market entry involves the risk that investments are not amortized because technologically advanced products are waiting just around the corner.

The contents and information value of the model are largely restricted to the initial stages of internationalization processes and have a rather reactive character, leaving little room for entrepreneurial strategic choice (Autio, Sapienza, & Almeida 2000).

Recent research findings concerning the phenomenon of new venture firms indicate that firms show a more rapid pace of internationalization; and, contrary to Johanson and Vahlne’s panel of Swedish enterprises, smaller rather than larger firms make large internationalization steps in a shorter period of time (Hashai & Almor 2004). International new venture firms tend to disregard domestic markets from their inception in favor of the international marketplace, which seems to be more attractive (Young, Dimitratos, & Dana 2003). These firms make use of globally knit personal relations, often fostered by the founding entrepreneur. Instead of focusing on ‘self-learning,’ knowledge about foreign markets can be acquired through relationships and interaction with other market actors (Forsgren 2002).

Furthermore, psychic distance is perceived differently by operating managers in international business. People develop subjective mental maps of space (e.g., foreign geographical location) and distance (e.g., culture and language) that need not necessarily correspond to reality. Therefore, it is hard to assume that international business performance naturally correlates with the degree (which is difficult to measure and to quantify) of psychic distance (Stottinger & Schlegelmilch 2000).

Accumulated internationalization knowledge that affects both business knowledge and institutional knowledge is not limited to specific country markets. Organization-specific experience in foreign business can be used in all markets (Eriksson et al. 1997). Therefore, Bjorkman and Forsgren (2000) argue that the model is less valid for very large multinational enterprises and firms with extensive international experience in high-technology industries. The Uppsala approach focuses on manufacturing products where production takes place in the domestic market, and the goods are sold at arm’s length in overseas markets. Therefore, the business activities of firms with digital business concepts, such as in the service industry where manufacture and delivery are inseparable, do not fit into the export-based Uppsala model for the process of internationalization (Jones 2001).

The Uppsala concept concentrates on experiential learning through independent commitment decisions and a firm’s own business activities abroad. However, firms are occasionally forced to follow their clients when they enter foreign markets. The Uppsala model is not able to accept the possibility of imitative learning, i.e., monitoring other firms acting in a similar way and assimilating from them. An organization can also look for radically new alternatives alongside current business modes and decide on market entry according to the forecasted market opportunities and not according to its current level of foreign business experience (Jones & Coviello 2002). Thus, the possible internationalization routes are more multifaceted than anticipated by the Uppsala model (Forsgren 2002).

Several decades after publishing the Uppsala concept in the academic literature, Johanson and Vahlne (2003) concluded that firm behaviors and economic and regulatory environments have changed considerably or did not exist when the Uppsala model was published at the end of the 1970s. Markets and industries have become increasingly integrated worldwide. Internationalization processes are characterized by networks of relationships in which firms are linked to each other in various complex patterns. Instead of focusing on a single firm’s progress in ‘self-learning’ and ‘knowledge accumulation’ as recommended in Uppsala, internationalization processes should be seen from a business network perspective of the environment faced by an internationalizing firm (Johanson & Vahlne 2009). The network theory of internationalization is introduced and explained in the next section of this book.

Source: Glowik Mario (2020), Market entry strategies: Internationalization theories, concepts and cases, De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 3rd edition.

What’s up it’s me, I am also visiting this web site daily, this website is really good and the people are really sharing pleasant thoughts.