The order in which prompts are presented to respondents, whether on the questionnaire or screen, shown on a card or read out, can have a significant effect on the responses recorded. Such bias can occur with the presentation of:

- scalar responses;

- monadically rated batteries of attitude or image dimensions;

- lists from which responses are chosen.

The questionnaire writer must consider how to minimize the order bias for each of these.

1. Scalar responses

A considerable amount has been written about the effect that the order of presentation of prompted alternative answers has on responses. Artingstall (1978) showed that when respondents are given a scale from which to choose a response in face-to-face interviewing they are significantly more likely to choose the first response offered than the last. Of 72 end items that were offered in his test, 62 were given greater endorsement when offered first. This is known as ‘the primacy effect’.

Thus if the positive end of a scale is always presented first a more favourable result will be found than if the negative end of the scale is always first. The finding held for any length of scale, and was independent of the demographic profile of the respondents. The difference was shown to be an increase of about 8 per cent to the positive responses.

What this and other work show is that the order of presentation has an effect. It does not say which order gives the best representation of the truth. However, it underlines the need to be consistent in the order in which scales are shown if comparisons are to be made between studies.

One approach to dealing with the bias is to rotate the order of presentation between two halves of the sample. This does not remove the bias but at least has the effect of averaging it.

In new product development research, it is not uncommon always to have the negative response presented first on scales rating the concept or the product. This then gives the least favourable response pattern, thereby providing a tougher test for the new product and ensuring that any positive reaction to the idea of the product is not overstated.

When visual prompts are used, the primacy effect is noticed, as demonstrated by Artingstall, as respondents notice and process the possible responses in the order that they are presented. Where prompts are read out, a recency effect is more marked, as respondents remember better the last option or last few options that they have been given. This effect has been demonstrated by Schwarz, Hippler and Noelle-Neumann (1991). With telephone interviewing, therefore, a recency effect should be expected, unless respondents are asked to write down the scale for reference before answering the question.

2. Batteries of statements

2.1. Fatigue effect

Where there is a large battery of either image or attitude statements, each of which is to be answered according to a scale, there is a real danger of respondent fatigue. This can occur both with self-completion batteries and where the interviewer reads them out. As discussed in Chapter 5, the precise point at which respondent fatigue is likely to set in will vary with the level of interest that each respondent has in the subject. However, it should be anticipated that, where there are more than about 30 statements, later statements are likely to suffer from inattention and pattern responding. To alleviate this type of bias, the presentation of the statement should be rotated between respondents. With electronic questionnaires, statements can often be presented in random order, or in rotation in a number of different sequences.

With paper questionnaires, rotating the order requires producing a number of different versions for self-completion, or careful instruction to interviewers if they are to read them out.

In the latter case it is common for the starting point on the battery for each respondent to be ticked or checked at the time of printing the questionnaires or before they are sent out to the interviewers. Ideally, the start point can be rotated between questionnaires so that the reading out starts at each statement an equal number of times. However, it may not always be possible to print this on automatically. It requires as many different versions of the page to be printed as there are statements in the battery. With possibly up to 30 statements the potential for error is considerable. Printing the questionnaire with no marked start points and marking each questionnaire by hand can be time-consuming where there are thousands of questionnaires. An alternative, which is usually acceptable, is to have a limited number of start points, and these can be printed using different versions of the page. Thus if there are 30 statements, six different start points can be used, spread throughout the battery. The statements are still reasonably well rotated and, with only six versions of the page to be printed, the scope for error is much reduced.

Where the battery of statements is to be read out by the interviewer using a paper questionnaire, it is important that every interviewer understands the process of rotating start points. In particular, interviewers must understand that every statement must be read out. It has been known for interviewers to read out only the statements from the designated start point to the end of the battery, and not to return to the beginning of the battery for the remaining statements. This is more likely to occur where the battery is on more than one page and the start point is not on the first page.

2.2. Statement clarification

The order in which statements are presented to respondents can sometimes be used to clarify their meanings. If there is a degree of ambiguity in a statement that would require a complex explanation, a preceding statement that deals with the alternative meaning can clarify what the questionnaire writer is seeking.

For example:

How would you rate the station for:

The facilities and services at the station

On its own, it could be unclear to respondents whether car parking should be considered as one of the facilities or services at the station. If, however, this statement is preceded by one about car parking:

Facilities for car parking

The facilities and services at the station

or, even better:

Facilities for car parking

Other facilities and services at the station

then respondents can safely assume that the facilities and services are not meant to include car parking as that has already been asked about.

Where random presentation of statements is used, care must be taken to ensure that such explanatory pairs of statements always appear together and in the same order.

3. Response lists

Showing a list of alternative responses is a common form of prompting in order to make respondents choose from a fixed set of options. For example:

Thinking about the advertisement that you have just seen, which of the phrases on this card would you say describes it? You can mention as many or as few phrases as you wish.

A It was difficult to understand

B It made me more interested in visiting the store

C I found it irritating

D It’s not right for this type of product

E I quickly got bored with it

F I did not like the people in it

G It said something relevant to me

H I will remember it

I It improved my opinion of the store

J It told me something new about the store

K It was aimed at me

L I enjoyed watching it

M None of these

The respondent is expected to read through all of the options and select those that apply. In this question, respondents can choose as many statements as they feel are appropriate. In other questions, they may be asked to choose one option or any other specified number.

3.1. Primacy and recency effects

Similar primacy effects as are seen with scales should be expected. The effects have been demonstrated by Schwarz, Hippler and Noelle- Neumann (1991), even where there are a small number of possible responses, down to three or even two if they are sufficiently complex to dissuade respondents from making an effort to process the possible answers in full. Duffy (2003) confirms the existence of primacy effects and adds that a significant minority read the list from the bottom. This would suggest that a recency effect can also be expected.

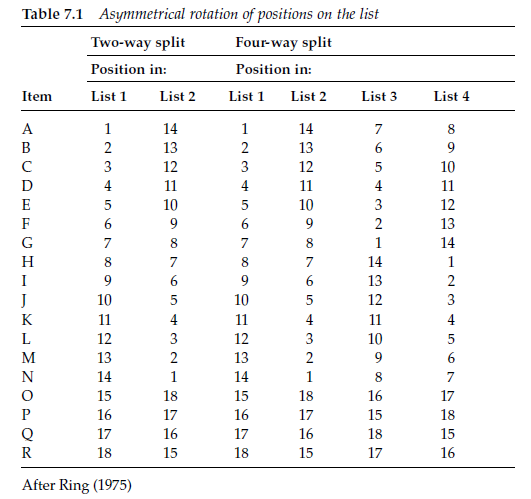

Indeed, both primacy and recency effects have been demonstrated by Ring (1975). He showed that with a list of 18 items there is a bias in favour of choosing responses in the first six and the last four positions (Table 7.1). The implication is that those in the middle of the list either are not read at all by some respondents or are not processed as possible responses to the same extent.

Where a list is of such size, then reversing the order and presenting one order to half of the sample and the reverse order to the other half does not adequately address the problem. Ring’s experiments showed that with a list of 18 items the first 14 should be reversed and the last four reversed. The items that were fourteenth and fifteenth in the initial list then become first and last in the alternative list. This asymmetrical split better balances the bias across the items than simply reversing them. For further reduction in order bias Ring suggests additional splits after the seventh and sixteenth items, but for most research purposes these are not necessary.

In practice, many, if not most, researchers satisfy themselves with two or at most four rotations. With electronic questionnaires, statements can often be presented in random order, or in rotation in a larger number of different sequences. This does not eliminate bias but spreads it across the statements more evenly.

3.2. Satisficing

Some people when buying items such as a washing machine, stereo system or car will spend a great deal of time researching which of the available models best meets their needs and requirements. Other people will buy one that satisfactorily meets their needs and requirements, and are not prepared to invest the time in researching all of the available models to determine whether there is one that is marginally better. The latter approach is known as ‘satisficing’, and occurs when choosing attitude statements from a list.

When presented with a list of statements from which to choose a response, satisficers will read it until they find an adequate answer that they feel reasonably reflects their view, or that they think will be acceptable to the interviewer, rather than reading or listening to all of the statements to find the answer that best reflects their view. This is another source of order bias, which will tend to reinforce the primacy effect.

Satisficing is likely to increase with interview fatigue as respondents stop making the effort to answer to the best of their ability. It is also likely to be more prevalent with telephone than with face-to-face interviewing (Holbrook, Green and Krosnick, 2003).

Source: Brace Ian (2018), Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research, Kogan Page; 4th edition.

Fastidious response in return of this question with

solid arguments and explaining everything about that.