How should a global enterprise organize to best exploit market opportunities throughout the world? How should it group its diverse activities? How should it coordinate them? What should be the authority and responsibility of managers at corporate, regional, and country levels? What should be the reporting and control relationships between these three levels? In sum, how should a global enterprise bring together its worldwide operations to structure an integrated global enterprise system?

All global enterprises must resolve these questions, but they may resolve them in several different ways. To be effective, an international organization must bring to managers three fundamental competencies at the times and places they are needed for decision making: functional (finance, marketing, production, and others), product (including allied technology), and geographical. The most basic question in organization design, therefore, is whether line operations should be subdivided according to major functions, major product lines, major geographical areas, or some mix of them.

1. Evolution of Organization Structure

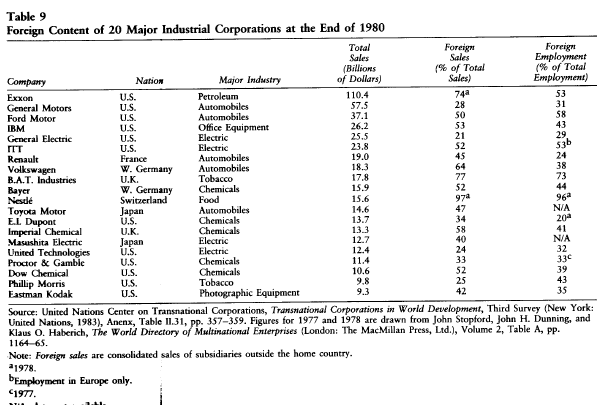

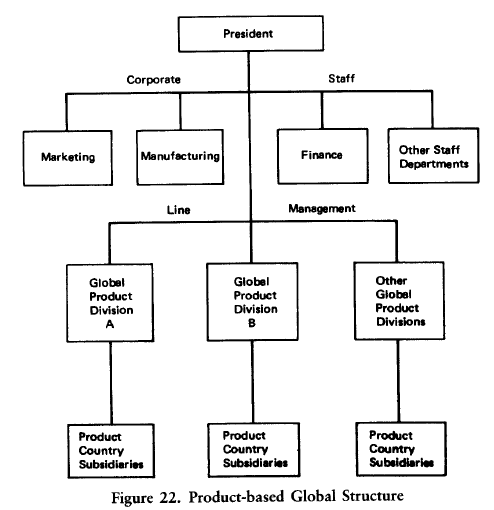

As an enterprise becomes more international, its organization structure also evolves in response to shifts in international strategies. Table 10 indicates the most common organization structures at different stages of the evolutionary scheme first introduced in Table 3 in Chapter 1.

In stage 1, a company’s foreign business is marginal and probably intermittent. Since it has no international strategy, it has no need to redesign its organization. At most, a stage 1 company may set up a built-in export department, consisting of a manager and a few assistants, at a level in the corporate structure below domestic sales.

In stage 2, a company adopts a strategy of exploiting foreign markets through direct exports. This new strategy creates a need for the full- function export department at the same level as the domestic sales department or even an export division headed by a corporate vice president.

A company moves into stage 3 when it enters one or more foreign markets through investment in local production. This shift in international strategy marks a critical step in the evolution of a global enterprise. For the first time, the company commits substantial financial, management, and technical resources to a foreign venture. To a far greater extent than ever before, investment entry brings top corporate management into decisions about international business. As the company adds to the number of its country subsidiaries while also serving country markets with exports and contractual arrangements, the need to manage all its international operations in a unified way under a common corporate strategy is signaled by failures to coordinate export, licensing, investment, and other foreign activities. Most U.S. companies respond to this need by creating an international division headed by a director of international operations, who is also a corporate vice president, holding line authority over all international operations.

When a company evolves to stage 4, the international division may account for one-third or more of total corporate sales and profits. The prominence of international business attracts managers to a global strategy that integrates domestic and international business at top corporate levels. This basic shift in strategy calls for new organization: a restructuring of the international division so that it becomes more intimately linked with the corporate staff and domestic divisions; a global organization that eliminates any corporate distinction between domestic and international business; or a mixed corporate structure.

The organization changes that occur as a company evolves into a global enterprise demonstrate the proposition, “Structure follows strategy.” Shifts in international business strategy demand changes in organization structure to manage that strategy. But organization changes do not come easily. Substantive differences among managers about the form of reorganization, as well as personalities, rivalries, politics, fears, and sheer inertia, act to delay structural responses until it becomes impossible to ignore critical failures of the existing organization. Even then, reorganization may occur piecemeal over a long period of time. To say that a company should have an organization structure that promotes and sustains its global strategy is true. But at any given time, a company’s organization most probably lags behind its strategy and is in transition to a new structure. We now turn to a brief description of the principal organizational alternatives for the global enterprise.

2. International Division

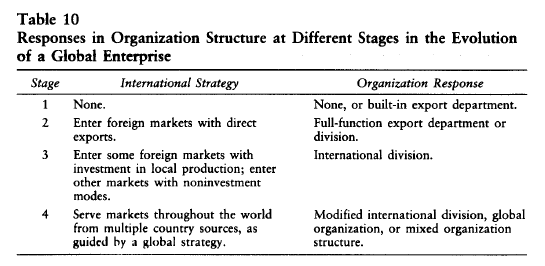

Most multiproduct U.S. companies are already organized by domestic product divisions when they make their first overseas investments in foreign production. The most common organizational response to this new strategy, therefore, is the creation of an international division at the same corporate level as the domestic product divisions.2 This form of organization is depicted in Figure 21.

The formation of an international division represents a decision to place corporate business into two separate categories based on geography. This organization appeals strongly to a stage 1 company, in which few, if any, executives have international experience. Since the international vice president reports directly to the president, only those two top executives need to be directly involved in foreign operations. On the positive side, the international division makes possible a single, coordinated management of international business across products and countries. It develops the specialized skills and experience needed to plan, execute, and control international programs. Established as a profit center, the international division encourages a concentrated drive to expand a company’s international business.

The weaknesses of the international division stem mostly from its separation from the domestic product divisions and from corporate staff. Lacking its own product/technology skills, the international division may not be able to support fully its foreign subsidiaries. Although the international division can develop its own functional staffs, they are unlikely to match the resources of corporate functional staffs, and they also represent some duplication of effort. In sum, its isolation from the rest of the corporation may render an international division unable to carry out the global strategy of a stage 4 enterprise. But this is not necessarily the case, because the international division can be a very flexible organization structure. Over time, dotted-line and other arrangements can build effective communication channels between an international division and the domestic divisions, and corporate staff can assume international responsibilities in direct support of the international division. Again, a top-level management committee with members drawn from the domestic and international divisions can be established to coordinate operations across the entire enterprise. In short, an international division may allow a company to achieve a substantial degree of integration between its domestic and international business. However, some companies in stage 4 may abandon the international division in favor of an organization that transfers international responsibility to all operating divisions, that is to say, a global structure based on product or geography.

3. Global Structure Based on Product

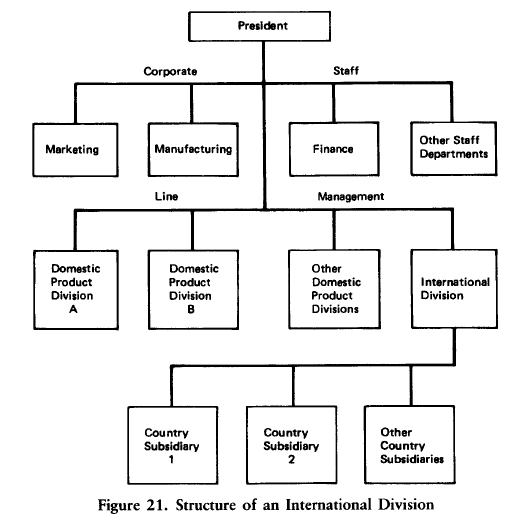

Companies that have several product lines with distinctive technologies and end uses, such as chemical and electrical-product companies, find a global structure based on product to be more beneficial than one based on geography. This structure is shown in Figure 22.

With the product-based global structure, the vice presidents of the respective product divisions become responsible for the production and marketing of their products throughout the world. These operating divisions are supported by corporate staff departments that now have a global responsibility for their functions. Hence the product-based global structure enables an enterprise to undertake worldwide strategies for diverse product lines. Country subsidiaries report directly to a corporate product division, from which they receive product and technical information and skills. In brief, this structure encourages a concentrated focus on product strategies that cover the world. …….

This emphasis on product means a deemphasis of geography. Consequently, division managers may ignore country differences that limit the effectiveness of standardized global strategies. Efforts by product divisions to develop their own area specialists are apt to be uneven and duplicative for the corporation as a whole. Also, a global enterprise may end up with several subsidiaries in the same foreign country reporting to different product divisions, with no one at headquarters responsible for the overall corporate presence in that country. The product-based global structure, like the area-based structure, is critically dependent on the availability of internationally oriented managers to head the several operating divisions and corporate staff departments.

4. Global Structure Based on Area

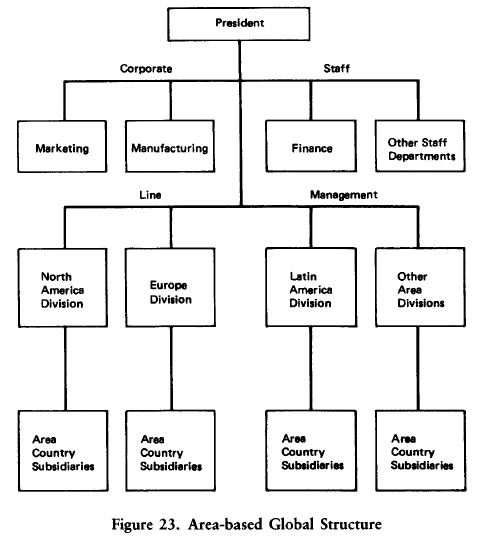

Companies with product lines that have similar technologies and common end-use markets, such as beverage, food, automotive, and pharmaceuticals companies, are attracted to the area-based global structure depicted in Figure 23.

With this organization, the division vice presidents are responsible for operations across all product lines in their respective areas. Emphasis on geographical areas makes this structure well suited to carrying out international strategies that must be sensitive to country differences. It therefore encourages adaptive foreign marketing programs. For that reason, consumer-products companies favor an area-based global structure. The major drawback of this structure is the deemphasis of product/technology competencies necessary to support area manufacturing and marketing oper-ations. Since each area division develops its own product specialists, some duplication of staff across divisions is a likely outcome. This structure may also foster area autonomy, posing obstacles to the creation of truly global strategies.

5. Mixed Structures

Mixed organization structures are common in global enterprises. Frequently, they are the adventitious consequence of piecemeal adaptations to new international strategies. In particular, an international division may be slowly dismantled as certain product divisions take on global responsibilities while others remain domestic or certain areas are transferred to area divisions while other areas are not. But mixed structures may also represent efforts to obtain the advantages of pure forms of organization while limiting their disadvantages. For example, an international division may be retained to provide area expertise to global product divisions in a staff relationship. Or some product lines may be managed through global product divisions while other product lines are administered through area divisions.

We have observed that each of the three organization structures described suffers from weaknesses, because the choice of one competency as the basis of line operations means that other competencies must either be provided at lower levels in line operations (with some duplication across divisions) or be concentrated in corporate staff departments. The most ambitious structure to overcome this problem is the matrix organization, which gives equal importance to functional, product, and geographical competencies. But to do so, it abandons the principle of unity of command: single lines of authority and accountability in a hierarchical system. Thus in a matrix organization, country managers are accountable to functional, product, and area managers at corporate headquarters. For the matrix structure to work, managers must be willing to participate in much committee and team management. Decision making becomes a slow process, but presumably decisions, once taken, are quickly implemented, because functional, product, and area managers are involved from the start. Only a handful of global enterprises have adopted a matrix structure for the entire corporation, but many more have tried it for certain product lines or geographical areas. One thing is certain: global enterprises will continue to respond to strategy shifts in a changing world with new forms of organization.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

Keep up the great piece of work, I read few blog posts on this internet site and I think that your website is very interesting and holds sets of good info .

Perfect work you have done, this internet site is really cool with great info .