There are some research designs that may be classified in the typology described above but, because of their uniqueness and prevalence, have acquired their own names. They are therefore described separately below.

1. The cross-over comparative experimental design

The denial of treatment to the control group is considered unethical by some professionals. In addition, the denial of treatment may be unacceptable to some individuals in the control group, which could result in them dropping out of the experiment and/ or going elsewhere to receive treatment. The former increases ‘experimental mortality’ and the latter may contaminate the study. The cross-over comparative experimental design makes it possible to measure the impact of a treatment without denying treatment to any group, though this design has its own problems.

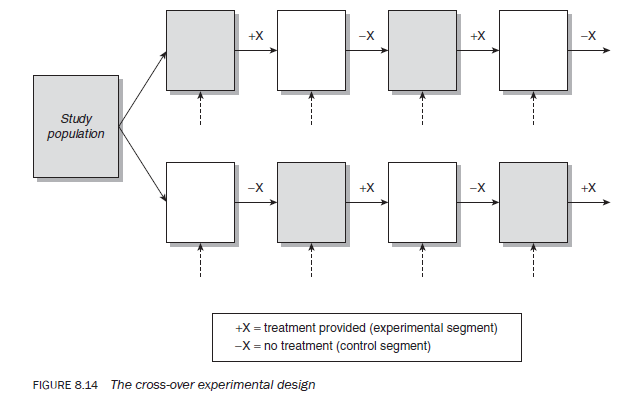

In the cross-over design, also called the ABAB design (Grinnell 1993: 104), two groups are formed, the intervention is introduced to one of them and, after a certain period, the impact of this intervention is measured. Then the interventions are ‘crossed over’; that is, the experimental group becomes the control and vice versa, sometimes repeatedly over the period of the study (Figure 8.14). However, in this design, population groups do not constitute experimental or control groups but only segments upon which experimental and control observations are conducted.

One of the main disadvantages of this design is discontinuity in treatment. The main question is: what impact would intervention have produced had it not been provided in segments?

2. The replicated cross-sectional design

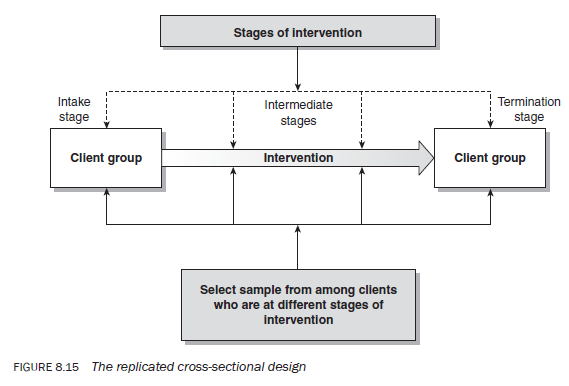

In practice one usually examines programmes already in existence and ones in which clients are at different stages of an intervention. Evaluating the effectiveness of such programmes within a conventional experimental design is impossible because a baseline cannot be established as the intervention has already been introduced. In this situation, the usual method of selecting a group of people who were recently recruited to the programme and following them through until the intervention has been completed may take a long time. In such situations, it is possible to choose clients who are at different phases of the programme to form the basis of your study (Figure 8.15).

This design is based upon the assumption that participants at different stages of a programme are similar in terms of their socioeconomic-demographic characteristics and the problem for which they are seeking intervention. Assessment of the effectiveness of an intervention is done by taking a sample of clients at different stages of the intervention. The difference in the dependent variable among clients at intake and termination stage is considered to be the impact of the intervention.

3. Trend studies

If you want to map change over a period, a trend study is the most appropriate method of investigation. Trend analysis enables you to find out what has happened in the past, what is happening now and what is likely to happen in the future in a population group. This design involves selecting a number of data observation points in the past, together with a picture of the present or immediate past with respect to the phenomenon under study, and then making certain assumptions as to future trends. In a way you are collecting cross-sectional observations about the trend being observed at different points in time over past—present—luture. From these cross-sectional observations you draw conclusions about the pattern of change.

Trend studies are useful in making forecasting by extrapolating present and past trends thus making a valuable contribution to planning. Trends regarding the phenomenon under study can be correlated with other characteristics of the study population. For example, you may want to examine the changes in political preference of a study population in relation to age, gender, income or ethnicity. This design can also be classified as retrospective- prospective study on the basis of the reference period classification system developed earlier in this chapter.

4. Cohort studies

Cohort studies are based upon the existence of a common characteristic such as year of birth, graduation or marriage, within a subgroup of a population. Suppose you want to study the employment pattern of a batch of accountants who graduated from a university in 1975, or study the fertility behaviour of women who were married in 1930. To study the accountants’ career paths you would contact all the accountants who graduated from the university in 1975 to find out their employment histories. Similarly, you would investigate the fertility history of those women who married in 1930. Both of these studies could be carried out either as cross-sectional or longitudinal designs. If you adopt a cross-sectional design you gather the required information in one go, but if you choose the longitudinal design you collect the required information at different points in time over the study period. Both these designs have their strengths and weaknesses. In the case of a longitudinal design, it is not important for the required information to be collected from the same respondents; however, it is important that all the respondents belong to the cohort being studied; that is, in the above examples they must have graduated in 1975 or married in 1930.

5. Panel studies

Panel studies are similar to trend and cohort studies except that in addition to being longitudinal they are also prospective in nature and the information is always collected from the same respondents. (In trend and cohort studies the information can be collected in a cross-sectional manner and the observation points can be retrospectively constructed.) Suppose you want to study the changes in the pattern of expenditure on household items in a community. To do this, you would select a few families to find out the amount they spend every fortnight on household items.You would keep collecting the same information from the same families over a period of time to ascertain the changes in the expenditure pattern. Similarly, a panel study design could be used to study the morbidity pattern in a community.

6. Blind studies

The concept of a blind study can be used with comparable and placebo experimental designs and is applied to studies measuring the effectiveness of a drug. In a blind study, the study population does not know whether it is getting real or fake treatment or which treatment modality. The main objective of designing a blind study is to isolate the placebo effect.

7. Double-blind studies

The concept of a double-blind study is very similar to that of a blind study except that it also tries to eliminate researcher bias by concealing the identity of the experimental and placebo groups from the researcher. In other words, in a double-blind study neither the researcher nor the study participants know who is receiving real and who is receiving fake treatment or which treatment model they are receiving.

Source: Kumar Ranjit (2012), Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners, SAGE Publications Ltd; Third edition.

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back often!