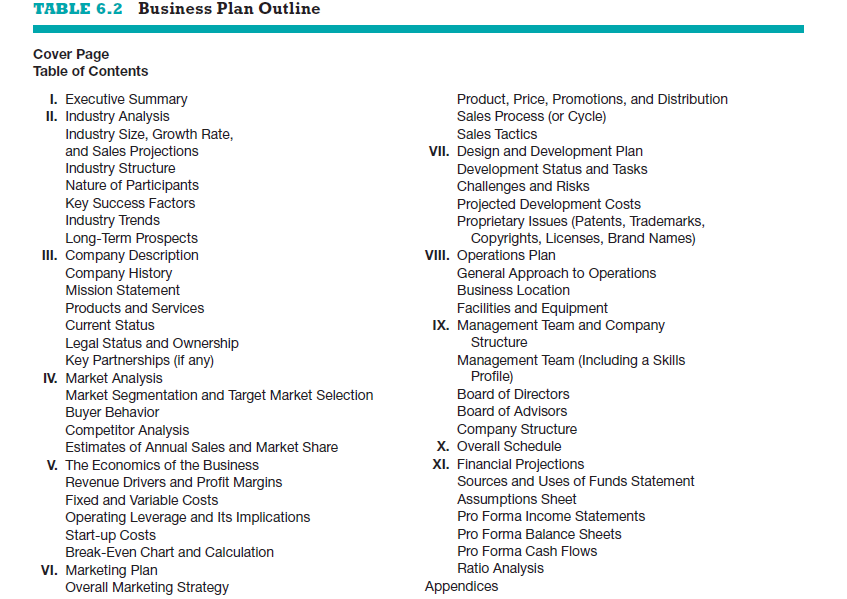

A suggested outline of the full business plan appears in Table 6.2. Specific plans may vary, depending on the nature of the business and the personalities of the founding entrepreneurs. Most business plans do not include all the elements introduced in Table 6.2; we include them here for the purpose of completeness.

1. Exploring each section of the Plan

Cover Page and Table of Contents The cover page should include the company’s name, address, and phone number; the date; the contact informa- tion for the lead entrepreneur; and the company’s website address if it has one. The company’s Facebook page and Twitter name can also be included. The contact information should include a land-based phone number, an e-mail address, and a smartphone number. This information should be centered at the top of the page. Because the cover letter and the business plan could get separated, it is wise to include contact information in both places. The bottom of the cover page should include information alerting the reader to the confi- dential nature of the plan. If the company already has a distinctive trademark, it should be placed somewhere near the center of the page. A table of contents should follow the cover letter. It should list the sections and page numbers of the business plan and the appendices.

Executive Summary The executive summary is a short overview of the entire business plan; it provides a busy reader with everything she needs to know about the new venture’s distinctive nature.19 As mentioned earlier, in many instances an investor will first ask for a copy of a firm’s PowerPoint deck or executive summary and will request a copy of the full business plan only if the PowerPoint deck or executive summary is sufficiently convincing. Thus, certainly when requested, the executive summary arguably becomes the most important section of the business plan.20 The most critical point to remember when writing an executive summary is that it is not an introduc- tion or preface to the business plan; instead, it is meant to be a summary of the plan itself.

An executive summary shouldn’t exceed two single-spaced pages. The cleanest format for an executive summary is to provide an overview of the business plan on a section-by-section basis. The topics should be presented in the same order as they are presented in the business plan. Two identical versions of the executive summary should be prepared—one that’s part of the business plan and one that’s a stand-alone document. The stand-alone document should be used to accommodate people who ask to see the executive summary before they decide whether they want to see the full plan.

Even though the executive summary appears at the beginning of the business plan, it should be written last. The plan itself will evolve as it’s writ- ten, so not everything is known at the outset. In addition, if you write the executive summary first, you run the risk of trying to write a plan that fits the executive summary rather than thinking through each piece of the plan independently.21

Industry analysis The main body of the business plan begins by describ- ing the industry in which the firm intends to compete. This description should include data and information about various characteristics of the industry, such as its size, growth rate, and sales projections. It is important to focus strictly on the business’s industry and not its industry and target market si- multaneously. Before a business selects a target market, it should have a good grasp of its industry—including where its industry’s promising areas are and where its points of vulnerability are located.

Industry structure refers to how concentrated or fragmented an industry is.22 Fragmented industries are more receptive to new entrants than industries that are dominated by a handful of large firms. You should also provide your reader a feel for the nature of the participants in your industry. Issues such as

whether the major participants in the industry are innovative or conservative and are quick or slow to react to environmental changes are the types of char- acteristics to convey. You want your reader to visualize how your firm will fit in or see the gap that your firm will fill. The key success factors in an industry are also important to know and convey. Most industries have 6 to 10 key fac- tors in which all participants must establish competence as a foundation for competing successfully against competitors. Most participants try to then dif- ferentiate themselves by excelling in two or three areas.

Industry trends should be discussed, which include both environmental and business trends. The most important environmental trends are economic trends, social trends, technological advances, and political and regulatory changes. Business trends include issues such as whether profit margins in the industry are increasing or declining and whether input costs are going up or down.The industry analysis should conclude with a brief statement of your beliefs regarding the long-term prospects for the industry.

Company Description This section begins with a general description of the company. Although at first glance this section may seem less critical than others, it is extremely important in that it demonstrates to your reader that you know how to translate an idea into a business.

The company history section should be brief, but should explain where the idea for the company came from and the driving force behind its inception. If the story of where the idea for the company came from is heartfelt, tell it. For example, the opening feature for Chapter 3 focuses on LuminAid, a solar light company that was started by Andrea Sreshta and Anna Stork, two Columbia University students. Sreshta and Stork’s motivation to design the light was spurred by their concern for people affected by a major earthquake that took place in Haiti in 2010. They experienced firsthand how a disaster can nega- tively impact the lives of millions. One thing most disaster victims suffer from is a lack of light. Sreshta and Stork started LuminAid to solve this problem. The LuminAid solar light is unique in that it can be shipped flat, and inflates when used to produce a portable, renewable source of light. The company’s goal is to make the LuminAid light a part of the supplies commonly sent as part of disaster relief efforts.

Sreshta and Stork’s story is heartfelt and is one with which anyone can relate. It might even cause one to pause and think, “That is a fantastic idea.

That’s just the type of solution that people recovering from a natural disaster like an earthquake need.”

A mission statement defines why a company exists and what it aspires to become.23 If carefully written and used properly, a mission statement can define the path a company takes and act as its financial and moral compass. Some businesses also include a tagline in their business plan. A tagline is a phrase that a business plans to use to reinforce its position in the marketplace. For example, Wello’s tagline is “Bye, Bye Gym Hello Convenience.” Wello is an online platform that allows participants to arrange workouts with trainers via Skype or another online means, which avoids having to make a trip to a gym to receive the same service.

The products and services section should include an explanation of your product or service. Include a description of how your product or service is unique and how you plan to position it in the marketplace. A product or ser- vice’s position is how it is situated relative to its rivals. If you plan to open a new type of smoothie shop, for example, you should explain how your smoothie shop differs from others and how it will be positioned in the market in terms of the products it offers and the clientele it attracts. This section is the ideal place for you to start reporting the results of your feasibility analysis. If the concept test, buying intentions survey, and library, Internet, and gumshoe research produced meaningful results, they should be reported here.

The current status section should reveal how far along your company is in its development. A good way to frame this discussion is to think in terms of milestones. A milestone is a noteworthy or significant event. If you have selected and registered your company’s name, completed a feasibility analy- sis, developed a business model, and established a legal entity, you have al- ready cleared several important milestones. The legal status and ownership section should indicate who owns the business and how the ownership is split up. You should also indicate what your current form of business own- ership is (i.e., LLC, Subchapter S Corp., etc.) if that issue has been decided. We provide a full discussion of the different forms of business ownership in Chapter 7.

A final item a business should cover in this opening section is whether it has any key partnerships that are integral to the business. Many business plans rely on the establishment of partnerships to make them work. Examples of the types of partnerships that are common in business plans are shown in the “Partnering for Success” feature.

Market analysis The market analysis is distinctly different from the indus- try analysis. Whereas the industry analysis focuses on the industry in which a firm intends to compete (e.g., toy industry, fitness center industry, men’s clothing industry), the market analysis breaks the industry into segments and zeroes in on the specific segment (or target market) to which the firm will try to appeal. As mentioned in Chapter 3, most start-ups focus on servicing a specific target market within an industry.

The first task that’s generally tackled in a market analysis is to segment the industry the business will be entering and then identify the specific target market on which it will focus. This is done through market segmentation, which is the process of dividing the market into distinct segments. Markets can be segmented in many ways, such as by geography (city, state, country), demographic variables (age, gender, income), psychographic variables (per- sonality, lifestyle, values), and so forth. Sometimes a firm segments its market based on more than one dimension in order to drill down to a specific segment that the firm thinks it is uniquely capable of serving. For example, in its mar- ket analysis, GreatCall, the cell phone service provided especially for older peo- ple, probably segmented the cell phone market by age and by benefits sought. Some start-ups create value by finding a new way to segment an industry.

For example, before Tish Ciravolo started Daisy Rock Guitar, a company that makes guitars just for women, the guitar industry had not been segmented by gender. Daisy Rock Guitar’s competitive advantage is that it makes guitars that accommodate a woman’s smaller hands and build.

It’s important to include a section in the market analysis that deals di- rectly with the behavior of the consumers in a firm’s target market. The more a start-up knows about the consumers in its target market, the more it can gear products or services to accommodate their needs. Many start-ups find it hard to sell products to public schools, for example, because purchase decisions are often made by committees (which draws out the decision-making process), and the funding often has to go through several levels of administrators before it can be approved. A competitor analysis, which is a detailed analysis of a firm’s competitors, should be included. We provided a thorough explanation of how to complete a competitor analysis in Chapter 5.

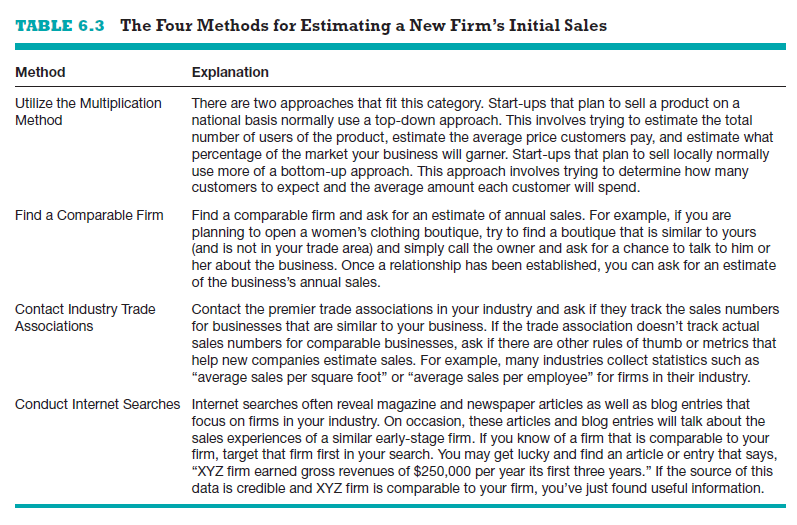

The final section of the market analysis estimates a firm’s annual sales and market share. There are four basic ways for a new firm to estimate its initial sales. If possible, more than one method should be used to complete this task. The most important outcome is to develop an estimate that is based on sound assumptions and seems both realistic and attainable. We show the four meth- ods entrepreneurs can use to estimate sales in Table 6.3.

The economics of the business This section begins the financial analy- sis of a business, which is further fleshed out in the financial projections. It addresses the basic logic of how profits are earned in the business and how many units of a business’s product or service must be sold for the business to “break even” and then start earning a profit.

The major revenue drivers, which are the ways a business earns money, should be identified. If a business sells a single product and nothing else, it has one revenue driver. If it sells a product plus a service guarantee, it has two revenue drivers, and so on. The size of the overall gross margin for each rev- enue driver should be determined. The gross margin for a revenue driver is the selling price minus the cost of goods sold or variable costs. The costs of goods sold are the materials and direct labor needed to produce the revenue driver.

So, if a product sells for $100 and the cost of goods sold is $40 (labor and materials), the gross margin is $60 or 60 percent. The $60 is also called the contribution margin. This is the amount per unit of sale that’s left over and is available to “contribute” to covering the business’s fixed costs and producing a profit. If your business has more than one revenue driver, you should figure the contribution margin for each. If you have multiple products in a given rev- enue driver category, you can calculate the contribution margin for each prod- uct and take an average. (For example, if you’re opening an office supply store, you may have several different computer printers under the revenue driver “printers.”) You can then calculate the weighted average contribution margin for each of the company’s revenue drivers by weighing the individual contribu- tion margin of each revenue driver based on the percentage of sales expected to come from that revenue driver.

The next section should provide an analysis of the business’s fixed and vari- able costs. The variable costs (or costs of goods sold) for each revenue driver was figured previously. Add a projection of the business’s fixed costs. A firm’s variable costs vary by sales, while its fixed costs are costs a company incurs whether it sells something or not. The company’s operating leverage should be discussed next. A firm’s operating leverage is an analysis of its fixed versus variable costs. Operating leverage is highest in companies that have a high proportion of fixed costs relative to their variable costs. In contrast, operating leverage is lowest in companies that have a low proportion of fixed costs rela- tive to variable costs. The implications of the firm’s projected operating leverage should be discussed. For example, a firm with a high operating leverage takes longer to reach break-even; however, once break-even is reached, more of its revenues fall to the bottom line.

The business’s one-time start-up costs should be estimated and put in a table. These costs include legal expenses, fees for business licenses and per- mits, website design, business logo design, and similar one-time expenses. Normal operating expenses should not be included.

This section should conclude with a break-even analysis, which is an analysis of how many units of its product a business must sell before it breaks even and starts earning a profit. In Chapter 8, we explain how to compute a break-even analysis.

Marketing Plan The marketing plan focuses on how the business will market and sell its product or service. It deals with the nuts and bolts of marketing in terms of price, promotion, distribution, and sales. For example, GreatCall, a firm producing cell phones for older users, may have a great product, a well-defined target market, and a good understanding of its cus- tomers and competitors, but it still has to find customers and persuade them to buy its product.

The best way to describe a company’s marketing plan is to start by ar- ticulating its marketing strategy, positioning, and points of differentiation, and then talk about how these overall aspects of the plan will be supported by price, promotional mix and sales process, and distribution strategy. Obviously, it’s not possible to include a full-blown marketing plan in the four to five pages permitted in a business plan for the marketing section, but you should hit the high points as best as possible.

A firm’s marketing strategy refers to its overall approach for marketing its products and services. A firm’s overall approach typically boils down to how it positions itself in its market and how it differentiates itself from competi- tors. GoldieBlox, the toy company introduced in Chapter 2, is positioning itself as a company that introduces girls to the field of engineering. Only about 10 percent of engineering jobs in the United States are held by women. Beginning with the assumption that storytelling will increase a young girl’s connection with the act of building, the company has created a set of toys intended to be used to solve problems while reading about adventures. The ultimate goal is to connect girls with the art of building and encourage young women to pursue careers in engineering. As we see with the example of GoldieBlox, the market- ing strategy sets the tone and provides guidance for how the company should reach its target market via its product, pricing, promotions, and distribution tactics. For example, it will invariably promote and advertise its products in places that young women and their parents are most likely to see. Similarly, it will most likely sell its products through specialty toy stores and its own web- site, along with mass merchandisers such as Toys“R”Us.

The next section should deal with your company’s approach to product, price, promotion, and distribution. If your product has been adequately ex- plained already, you can move directly to price. Price, promotion, and distribu- tion should all be in sync with your positioning and points of differentiation, as described previously. Price is a particularly important issue because it deter- mines how much money a company can make. It also sends an important mes- sage to a firm’s target market. If GoldieBlox advertised its toys as high-quality toys that are both educationally sound and environmentally friendly but also charged a low price, people in its target market would be confused. They would think, “This doesn’t make sense. Are GoldieBlox toys high quality or aren’t they?” In addition, the lower price wouldn’t generate the profits that GoldieBlox needs to further develop its toys. You should also briefly discuss your plans re- garding promotions and distribution.

The final section should describe the company’s sales process or cycle and specific sales tactics it will employ. It’s surprising how many business plans describe a business’s overall marketing strategies, but never comment on how a product or service will actually be sold.

Product (or Service) Design and Development Plan If you’re devel- oping a completely new product or service, you need to include a section in your business plan that focuses on the status of your development efforts. Many seemingly promising start-ups never get off the ground because their product development efforts stall or the actual development of the product or service turns out to be more difficult than expected.

The first issue to address is to describe the present stage of the develop- ment of your product or service. Most products follow a logical path of devel- opment that includes product conception, prototyping, initial production, and full production. You should describe specifically the point that your product or service is at and provide a timeline that describes the remaining steps. If you are in the very early stages of your business and only have an idea, you should carefully explain how a prototype, which is the first physical depiction of a new product or service, will be produced. A product prototype is the first physi- cal manifestation of a new product, often in a crude or preliminary form. The idea is to solicit feedback and then iterate. For example, a prototype of a prod- uct, like one of GoldieBlox’s toys, might consist of a preliminary version of the product for users to test and then report their experiences. GoldieBlox would then modify or tweak the toy based on the users’ experiences. Similarly, a pro- totype for a Web-based company might consist of a preliminary or beta version of the site, with sufficient functionality built into the site for users to test it and then provide feedback. In some instances a virtual prototype is sufficient. A virtual prototype is a computer-generated 3D image of a product or service idea. It displays the idea as a 3D model that can be viewed from all sides and rotated 360 degrees.

A section labeled “Challenges and Risks” should be included and disclose any major anticipated design and development challenges and risks that will be involved in bringing the product or service to market. While you want to remain upbeat, the last thing you want to do is paint an overly rosy picture of how quickly and effortlessly your design and development process will unfold.

Experienced readers know that product and service development is an inher- ently bumpy and challenging process, and they will want insights into the challenges and risks you anticipate with your particular offering.

A final section should describe any patents, trademarks, copyrights, or trade secrets that you have secured or plan to secure relative to the prod- ucts or services you are developing. If your start-up is still in the early stages and you have not taken action regarding intellectual property issues yet, you should get legal advice so you can, at a minimum, discuss your plans in these areas. Intellectual property is discussed in Chapter 12.

Operations Plan The operations plan section of the business plan outlines how your business will be run and how your product or service will be pro- duced. You have to strike a careful balance between adequately describing this topic and providing too much detail. Your readers will want an overall sense of how the business will be run, but they generally will not be looking for detailed explanations. As a result, it is best to keep this section short and crisp.

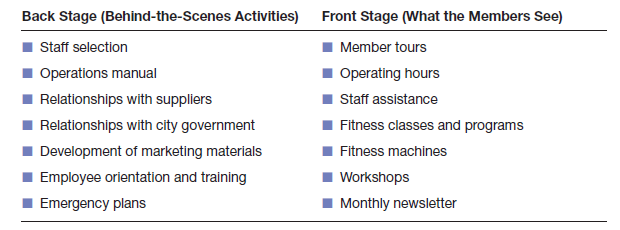

A useful way to illustrate how your business will be run is to first articulate your general approach to operations in terms of what’s most important and what the make-or-break issues are. You can then frame the discussion in terms of “back stage,” or behind-the-scenes activities, and “front stage,” or what the cus- tomer sees and experiences. For example, if you’re opening a new fitness center, the back-stage and the front-stage issues might be broken down as follows:

Obviously you can’t comment on each issue in the three to four pages you have for your operations plan, but you can lay out the key back-stage and front-stage activities and address the most critical ones.

The next section of the operations plan should describe the geographic location of your business. In some instances location is an extremely impor- tant issue, and in other instances it isn’t. For example, one of the reasons Jeff Bezos decided to locate Amazon.com in Seattle is that this city is a major distribution hub for several large book publishers. By locating near these dis- tribution facilities, Amazon.com has enjoyed a cost advantage that it wouldn’t have had otherwise. On a more fine-grained level, for restaurants and retail businesses, the specific location within a mall or shopping center, or a certain side of a busy street, may make a dramatic difference.

This section should also describe a firm’s facilities and equipment. You should list your most important facilities and equipment and briefly describe how they will be (or have been) acquired, in terms of whether they will be purchased, leased, or acquired through some other means. If you will be pro- ducing a product and will contract or outsource your production, you should comment on how that will be accomplished. If your facilities are nondescript, such as a generic workspace for computer programmers, it isn’t necessary to provide a detailed explanation.

Management Team and Company Structure Many investors and others who read business plans look first at the executive summary and then go directly to the management team section to assess the strength of the people starting the firm. Investors read more business plans with interesting ideas and exciting markets than they are able to finance. As a result, it’s of- ten not the idea or market that wins funding among competing plans, but the perception that one management team is better prepared to execute its idea than the others.

The management team of a new firm typically consists of the founder or founders and a handful of key management personnel. A brief profile of each member of the management team should be provided, starting with the founder or founders of the firm. Each profile should include the following information:

■ Title of the position

■ Duties and responsibilities of the position

■ Previous industry and related experience

■ Previous successes

■ Educational background

Although they should be kept brief, the profiles should illustrate why each individual is qualified and will uniquely contribute to the firm’s success. Certain attributes of a management team should be highlighted if they apply in your case. For example, investors and others tend to prefer team members who’ve worked together before. The thinking here is that if people have worked together before and have decided to partner to start a new firm, it usually means that they get along personally and trust one another.24 You should also identify the gaps that exist in the management team and your plans and time- table for filling them. The complete résumés of key management team person- nel can be placed in an appendix to the business plan.

If a start-up has a board of directors and/or a board of advisors, their qualifications and the roles they play should be explained and they should be included as part of your management team. A board of directors is a panel of individuals elected by a corporation’s shareholders to oversee the management of the firm, as explained in more detail in Chapter 9. A board of advisors is a panel of experts asked by a firm’s management to provide counsel and advice on an ongoing basis. Unlike a board of directors, a board of advisors possesses no legal responsibility for the firm and gives nonbinding advice.25 Many start- ups ask people who have specific skills or expertise to serve on their board of advisors to help plug competency gaps until the firm can afford to hire ad- ditional personnel. For example, if a firm is started by two Web designers and doesn’t have anyone on staff with marketing expertise, the firm might place one or two people on its board of advisors with marketing expertise to provide guidance and advice.

The final portion of this section of your business plan focuses on how your company will be structured. Even if you are a start-up, you should outline how the company is currently structured and how it will be structured as it grows. It’s important that the internal structure of a company makes sense and that the lines of communication and accountability are clear. Including a descrip- tion of your company’s structure also reassures the people who read the plan that you know how to translate your business idea into a functioning firm.

The most effective way to illustrate how a company will be structured and the lines of authority and accountability that will be in place is to include an organizational chart in the plan. An organizational chart is a graphic represen- tation of how authority and responsibility are distributed within the company. The organizational chart should be presented in graphical format if possible.

Overall Schedule A schedule should be prepared that shows the major events required to launch the business. The schedule should be in the format of milestones critical to the business’s success, such as incorporating the ven- ture, completion of prototypes, rental of facilities, obtaining critical financing, starting the production of operations, obtaining the first sale, and so forth. An effectively prepared and presented schedule can be extremely valuable in con- vincing potential investors that the management team is aware of what needs to take place to launch the venture and has a plan in place to get there.

Financial Projections The final section of a business plan presents a firm’s pro forma (or projected) financial projections. Having completed the pre- vious sections of the plan, it’s easy to see why the financial projections come last. They take the plans you’ve developed and express them in financial terms.

The first thing to include is a sources and uses of funds statement, which is a document that lays out specifically how much money a firm needs (if the intention of the business plan is to raise money), where the money will come from, and how the money will be used. The next item to include is an assumptions sheet, which is an explanation of the most critical assumptions on which the financial statements are based. Some assumptions will be based on general information, and no specific sources will be cited to substantiate the assumption. For example, if you believe that the U.S. economy will gain strength over the next three to five years, and that’s an underlying assump- tion driving your sales projections, then you should state that assumption. In this instance, you wouldn’t cite a specific source—you’re reflecting a consen- sus view. (It’s then up to your reader to agree or disagree.) Other assumptions will be based on very specific information, and you should cite the source for your assumptions. For example, if GoldieBlox has credible data showing that the educational segment of the children’s toy industry is expected to grow at a certain percentage each year for the foreseeable future, and this figure plays a large role in its belief that it can increase its sales every year, then it should cite the sources of its information.

The importance of identifying the most critical assumptions that a business is based on and thoroughly vetting the assumptions is illustrated in the “What Went Wrong” feature. EventVue, the company that is the focus of the feature, failed largely because several of the key assumptions that business was based on turned out to be incorrect.

The pro forma (or projected) financial statements are the heart of the financial section of a business plan. Although at first glance preparing financial statements appears to be a tedious exercise, it’s a fairly straightforward process if the preceding sections of your plan are thorough. The financial statements also represent the finale of the entire plan. As a result, it’s interesting to see how they turn out.

A firm’s pro forma financial statements are similar to the historical state- ments an established firm prepares, except they look forward rather than track the past. Pro forma financial statements include the pro forma income statement, the pro forma balance sheet, and the pro forma cash flow state- ment. They are usually prepared in this order because information flows logi- cally from one to the next. Most experts recommend three to five years of pro forma statements. If the company you’re writing your plan for already exists, you should also include three years of historical financial statements. Most business plan writers interpret or make sense of a firm’s historical or pro forma financial statements through ratio analysis. Ratios, such as return on assets and return on sales, are computed by taking numbers out of fi- nancial statements and forming ratios with them. Each ratio has a particular meaning in regard to the potential of the business.

We present a complete explanation of how to complete pro forma financial statements and ratio analysis in Chapter 8.

Appendix Any material that does not easily fit into the body of a business plan should appear in an appendix—résumés of the top management team, photos or diagrams of product or product prototypes, certain financial data, and market research projections. The appendix should not be bulky and add significant length to the business plan. It should include only the additional information vital to the plan but not appropriate for the body of the plan itself.

Putting it all Together In evaluating and reviewing the completed busi- ness plan, the writers should put themselves in the reader’s shoes to deter- mine if the most important questions about the viability of their business venture have been answered. Table 6.4 lists the 10 most important questions a business plan should answer. It’s a good checklist for any business plan writer.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

great put up, very informative. I’m wondering why the other experts of this sector don’t notice this. You must proceed your writing. I am confident, you have a huge readers’ base already!