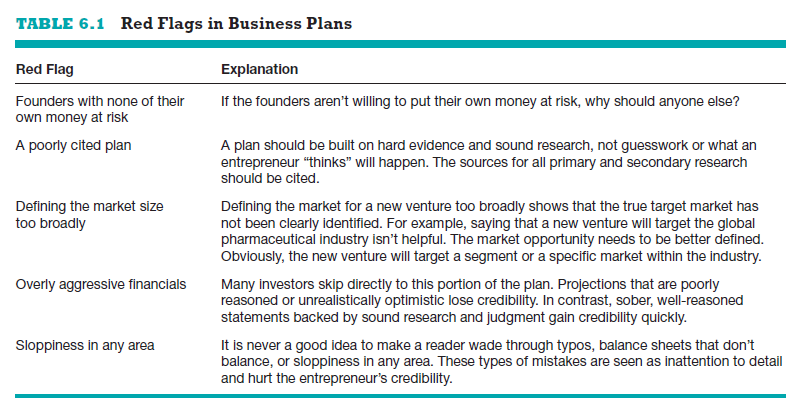

There are several important guidelines that should influence the writing of a business plan. It is important to remember that a firm’s business plan is typi- cally the first aspect of a proposed venture that an investor will see. If the plan is incomplete or looks sloppy, it is easy for an investor to infer that the venture itself is incomplete and sloppy.10 It is important to be sensitive to the struc- ture, content, and style of a business plan before sending it to an investor or anyone else who may be involved with the new firm. Table 6.1 lists some of the “red flags” that are raised when certain aspects of a business plan are insuf- ficient or miss the mark.

1. Structure of the Business Plan

To make the best impression, a business plan should follow a conventional structure, such as the outline shown in the next section. Although some en- trepreneurs want to demonstrate creativity in everything they do, departing from the basic structure of the conventional business plan format is usually a mistake. Typically, investors are very busy people and want a plan where they can easily find critical information. If an investor has to hunt for something be- cause it is in an unusual place or just isn’t there, he or she might simply give up and move on to the next plan.11

Many software packages are available that employ an interactive, menu- driven approach to assist in the writing of a business plan. Some of these pro- grams are very helpful.12 However, entrepreneurs should avoid a boilerplate plan that looks as though it came from a “canned” source. The software pack- age may be helpful in providing structure and saving time, but the information in the plan should still be tailored to the individual business. Some businesses hire consultants or outside advisers to write their business plans. Although there is nothing wrong with getting advice or making sure that a plan looks as professional as possible, a consultant or outside adviser shouldn’t be the pri- mary author of the plan. Along with facts and figures, a business plan needs to project a sense of anticipation and excitement about the possibilities that surround a new venture—a task best accomplished by the creators of the busi- ness themselves.13

2. Content of the Business Plan

The business plan should give clear and concise information on all the impor- tant aspects of the proposed new venture. It must be long enough to provide sufficient information, yet short enough to maintain reader interest. For most plans, 25 to 35 pages (and typically closer to 25 than 35 pages) are sufficient. Supporting information, such as the résumés of the founding entrepreneurs, can appear in an appendix.

After a business plan is completed, it should be reviewed for spelling, gram- mar, and to make sure that no critical information has been omitted. There are numerous stories about business plans sent to investors that left out impor- tant information, such as significant industry trends, how much money the company needed, or how the money was going to be used. One investor even told the authors of this book that he once received a business plan that didn’t include any contact information for the entrepreneur. Apparently, the entre- preneur was so focused on the content of the plan that he or she simply forgot to provide contact information on the business plan itself. This was a shame, because the investor was interested in learning more about the business idea.14

Style or Format of the business Plan The plan’s appearance must be carefully thought out. It should look sharp but not give the impression that a lot of money was spent to produce it. Those who read business plans know that en- trepreneurs have limited resources and expect them to act accordingly. A plastic spiral binder including a transparent cover sheet and a back sheet to support the plan is a good choice. When writing the plan, avoid getting carried away with the design elements included in word-processing programs, such as boldfaced type, italics, different font sizes and colors, clip art, and so forth. Overuse of these tools makes a business plan look amateurish rather than professional.15

One of the most common questions that the writers of business plans ask is, “How long and detailed should it be?” The answer to this question depends on the type of business plan that is being written. There are three types of business plans, each of which has a different rule of thumb regarding length and level of detail. Presented in Figure 6.2, the three types of business plans are as follows:

■ Summary plan: A summary business plan is 10 to 15 pages and works best for companies that are very early in their development and are not prepared to write a full plan. The authors may be asking for funding to conduct the analysis needed to write a full plan. Ironically, summary business plans are also used by very experienced entrepreneurs who may be thinking about a new venture but don’t want to take the time to write a full business plan. For example, if someone such as Drew Houston, the co-founder of Dropbox, was thinking about starting a new business, he might write a summary business plan and send it out to selected inves- tors to get feedback on his idea. Most investors know about Houston’s success with Dropbox and don’t need detailed information. Dropbox, the subject of Case 2.1, is a free file hosting service that was founded in 2007 and is now being used by more than 200 million people across the world.

■ Full business plan: A full business plan is typically 25 to 35 pages long.

This type of plan spells out a company’s operations and plans in much more detail than a summary business plan, and it is the format that is usually used to prepare a business plan for an investor.

■ Operational business plan: Some established businesses will write an operational business plan, which is intended primarily for an internal audience. An operational business plan is a blueprint for a company’s op- erations. Commonly running between 40 and 100 pages in length, these plans can obviously feature a great amount of detail that provides guid- ance to operational managers.

If an investor asks you for a PowerPoint deck or the executive summary of your business plan rather than the complete plan, don’t be alarmed. This is a common occurrence. If the investor’s interest is piqued, he or she will ask for more information. Most investors believe the process of writing a full business plan is important, even if they don’t ask for one initially. This sentiment is af- firmed by Brad Feld, a venture capitalist based in Boulder, Colorado, who wrote:

Writing a good business plan is hard. At one point it was an entry point for discus- sion with most funding sources (angels and VCs). Today, while a formal business plan is less critical to get in the door, the exercise of writing a business plan is in- credibly useful. As an entrepreneur, I was involved in writing numerous business plans. It’s almost always tedious, time consuming, and difficult but resulted in me having a much better understanding of the business I was trying to create.16

A cover letter should accompany a business plan sent to an investor or other stakeholders through the mail. The cover letter should briefly introduce the entrepreneur and clearly state why the business plan is being sent to the individual receiving it. As discussed in Chapter 10, if a new venture is looking for funding, a poor strategy is to obtain a list of investors and blindly send the plan to everyone on the list. Instead, each person who receives a copy of the plan should be carefully selected on the basis of being a viable investor candidate.

Recognizing the elements of the Plan May Change A final guide- line for writing a business plan is to recognize that the plan will usually change as it is being written and as the business evolves. New insights invari- ably emerge when entrepreneurs immerse themselves in writing the plan and start getting feedback from others. This process continues throughout the life of a company, and it behooves entrepreneurs to remain alert and open to new insights and ideas.

Because business plans usually change while being written, there is an emerging school of thought that opposes the idea of writing a business plan and advocates experimentation and trial-and-error learning gleaned through cus- tomer feedback over formal planning.17 This approach, which is associated with the Lean Startup movement, espouses many excellent ideas, particularly in the area of soliciting feedback directly from prospective customers prior to settling on a business idea and business model to execute on the idea. In this book, we take the opposite position, arguing that a business plan, proceeded by a feasibil- ity analysis, represents an important starting point for a new venture and serves many useful purposes. In this sense, those developing a business plan should understand that it is not intended to be a static document written in isolation at a desk. Instead, it is anticipated that the research conducted to complete the plan, and the preceding feasibility analysis, will place the founders in touch with potential customers, suppliers, business partners, and others, and that the feedback obtained from these key people will cause the plan to change as it’s be- ing written.18 It’s also anticipated that the business itself will iterate and change after it’s launched, based on additional feedback. Some businesses will change more than others, based on the quality of their initial feasibility analysis and the newness and volatility of their industry. These issues and related ones are con- sidered in the “Savvy Entrepreneurial Firm” feature.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

I as well believe hence, perfectly pent post! .

I have been reading out some of your articles and i can state pretty clever stuff. I will make sure to bookmark your site.