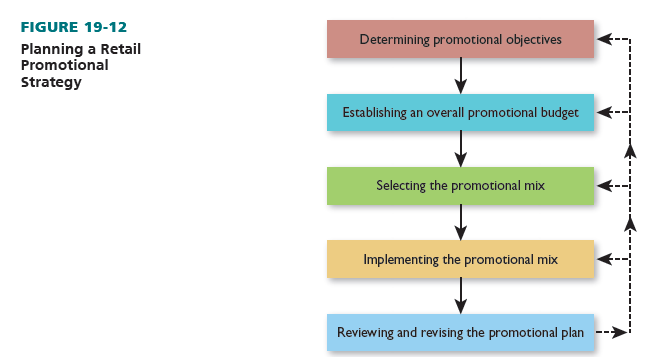

A systematic approach to promotional planning is shown in Figure 19-12 and explained next. Our blog site (www.bermanevansretail) has posts related to promotional strategy, including word of mouth.

1. Determining Promotional Objectives

A retailer’s broad promotional goals are typically drawn from this list. In developing a promotional strategy, the firm must determine which of these are most important:

- Increase sales.

- Stimulate impulse and reminder buying.

- Raise customer traffic.

- Get leads for sales personnel.

- Present and reinforce the retailer image.

- Inform customers about goods and services.

- Popularize new stores and Web sites.

- Capitalize on manufacturer support.

- Enhance customer relations.

- Maintain customer loyalty.

- Have consumers pass along positive information to friends and others.

It is vital to state goals as precisely as possible to give direction to the choice of promotional types, media, and messages. Increasing sales is not a specific goal. However, increasing sales by 10 percent is directional, quantitative, and measurable. With that goal, a firm would be able to prepare a thorough promotional plan and evaluate its success.

Perhaps the most vital long-term promotion goal for any retailer is to gain positive word of mouth (WOM), which occurs when one consumer talks to others—in person, on the phone, by E-mail, through social media, or in some other format. If a satisfied customer refers friends to a retailer, this can build into a chain of customers. No retailer can succeed if it receives extensive negative WOM (such as “The hotel advertised that everything was included in the price. Yet it cost me another $50 to play golf’). Negative WOM will cause a firm to lose substantial business.

Both goods- and services-oriented retailers must have positive word of mouth to attract new customers and retain existing customers. It has even greater importance given the widespread use of social media, where a single negative post or tweet can undo years of careful brand building.14 For example, many Netflix lapsed members who rejoin the service hear or read word-of-mouth messages by existing members. If Netflix does not satisfy existing members, it may not be able to attract new members, and the ability to maintain and grow the business will be adversely affected.15

2. Establishing an Overall Promotional Budget

There are five main procedures for setting the size of a retail promotional budget. Retailers should weigh the strengths and weaknesses of each technique in relation to their own requirements and constraints. To assist firms in their efforts, there is now computer software available.

With the all-you-can-afford method, a retailer first allots funds for each element of the retail strategy mix except promotion. The remaining funds go to promotion. This is the weakest technique. Its shortcomings are that little emphasis is placed on promotion as a strategic variable; expenditures are not linked to goals; and if little or no funds are left over, the promotion budget is too small or nonexistent. The method is used predominantly by small, conservative retailers.

The incremental method relies on prior promotion budgets to allocate funds. A percentage is either added to or subtracted from one year’s budget to determine the budget for next year. If this year’s promotion budget is $100,000, next year’s would be calculated by adjusting that amount. A 10 percent rise means that next year’s budget would be $110,000. This technique is useful for a small retailer. It provides a reference point. The budget is adjusted based on the firm’s feelings about past successes and future trends. It is easy to apply. Yet, the budget is rarely tied to specific goals; rather, “gut feelings’ are generally used.

With the competitive parity method, a retailer’s promotion budget is raised or lowered based on competitors’ actions. If the leading competitor raises its budget, other retailers in the area may follow. This method, often employed by both small and large firms, uses a comparison

point and is market-oriented and conservative. It also is imitative, takes for granted that tough-to- get competitive data are available, and assumes competitors are similar (as to years in business, size, customers, location, merchandise, prices, etc.). That last point is critical because competitors often need very different promotional budgets.

In the percentage-of-sales method, a retailer ties its promotion budget to revenue. A promotion-to-sales ratio is developed. Then, during succeeding years, this ratio remains constant. A firm could set promotion costs at 10 percent of sales. If this year’s sales are $600,000, there is a $60,000 promotion budget. If next year’s sales are estimated at $720,000, a $72,000 budget is planned. This process uses sales as a base, is adaptable, and correlates promotion and sales. Nonetheless, there is no relation to goals (for an established firm, sales growth may not require increased promotion); promotion is not used to lead sales; and promotion drops during poor periods, when increases might be helpful. This technique provides excess financing in times of high sales and too few funds in periods of low sales.

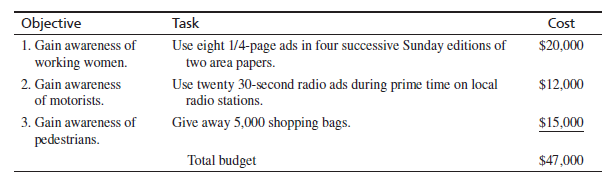

Under the objective-and-task method, a retailer clearly defines its promotion goals and prepares a budget to satisfy them. A goal might be to have 70 percent of the people in its trading area know a retailer’s name by the end of a one-month promotion campaign, up from 50 percent. To do so, it would determine the tasks and costs required to achieve that goal:

The objective-and-task method is the best budgeting technique. Goals are clear, spending relates to goal-oriented tasks, and performance can be assessed. However, it can be time consuming and complex to set goals and specific tasks, especially for small retailers.

3. Selecting the Promotional Mix

After a budget is set, the promotional mix is determined: the retailer’s combination of advertising, public relations, personal selling, and sales promotion. A firm with a limited budget may rely on store displays, Web site traffic, flyers, targeted direct mail, and publicity to generate customer traffic. One with a large budget may rely more on newspaper and TV ads. Retailers often use an assortment of forms to reinforce each other. A melding of media ads and point-of-purchse displays may be more effective than either form alone. See Figure 19-13.

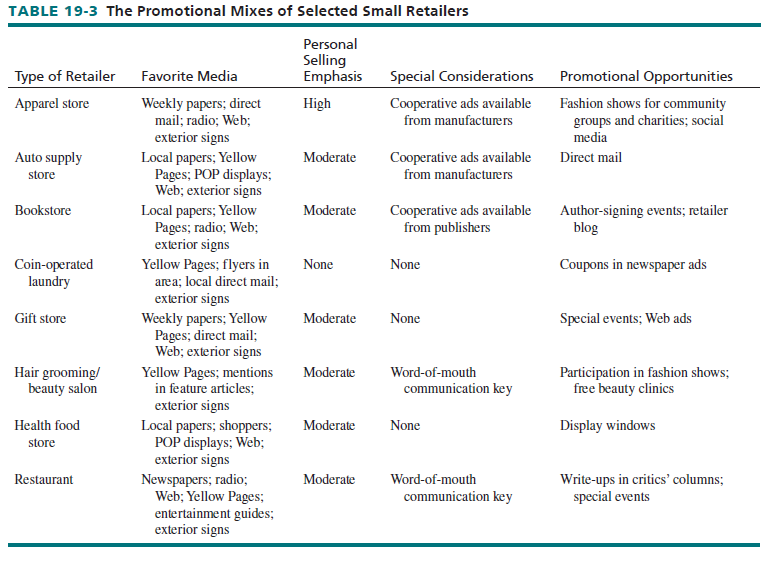

The promotional mix is affected by the type of retailer involved. In supermarkets, sampling, frequent shopper promotions, theme sales, and bonus coupons are among the techniques used most. At upscale stores, there is more attention to personal selling and less to advertising and sales promotion as compared with discounters. Table 19-3 shows a number of small-retailer promotional mixes.

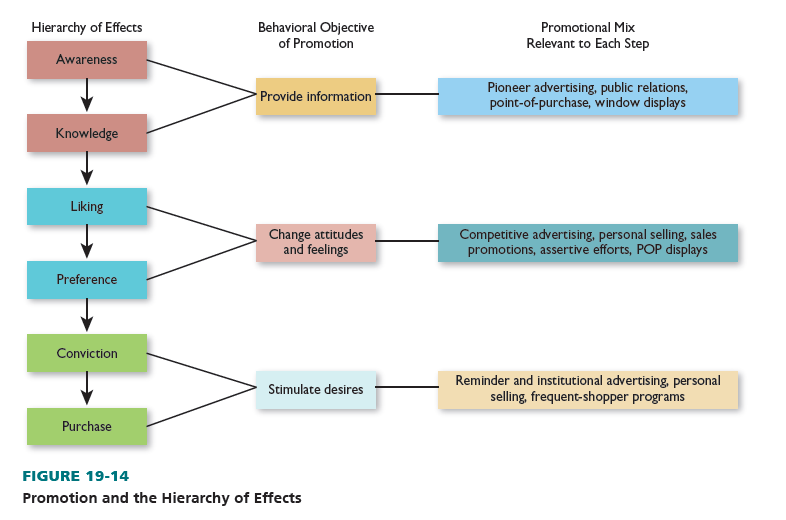

In reacting to a retailer’s communication efforts, consumers often go through a sequence of steps known as the, hierarchy of effects, which takes them from awareness, to knowledge, to liking, to preference, to conviction, to purchase. Different promotional mixes are needed in each step. Ads and public relations are best to develop awareness; personal selling and sales promotion are best in changing attitudes and stimulating desires. This is especially true for expensive, complex goods and services. See Figure 19-14.

4. Implementing the Promotional Mix

The implementation of a promotional mix involves choosing which specific media to use (such as Newspaper A and Newspaper B), timing, message content, the makeup of the sales force, specific sales promotion tools, and the responsibility for coordination.16

MEDIA DECISIONS The choice of specific media is based on their overall costs, efficiency (the cost to reach the target market), lead time, and editorial content. The retailer’s promotion budget is important since heavy use of one expensive medium may preclude a balanced promotional mix, and a firm may not be able to repeat a message in a costly medium.

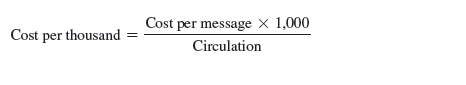

A medium’s efficiency relates to the cost of reaching a given number of target customers. Media rates are often expressed in terms of cost per 1,000 readers, watchers, or listeners:

A newspaper with a circulation of 400,000 and a one-page advertising rate of $10,000 has a per-page cost per thousand of $25.

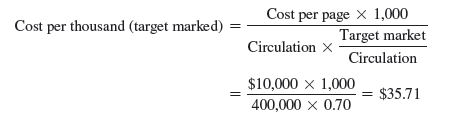

In this computation, total circulation is used to measure efficiency. Yet, because a retailer usually appeals to a limited target market, only the relevant portion of circulation should be considered. If 70 percent of readers are target customers for a particular firm (and the other 30 percent live outside the trading area), the real cost per thousand is:

Different media require different lead times. A newspaper ad can be placed shortly before publication and an online ad can sometimes go “live” almost immediately, whereas a print magazine ad sometimes must be placed months in advance. In addition, the retailer must decide what kind of editorial content it wants near ads (such as a sports story or a personal-care column).

Media decisions are not simple. Despite spending billions of dollars on TV and radio commercials, banner ads at search engines, and other media, many Web retailers have found the most valuable medium for them is E-mail. It is fast, inexpensive, and targeted. Consider the following example.

To generate greater awareness of Web retailers, costly advertising may be necessary in today’s competitive and cluttered landscape. Netflix has a broad mix of marketing and public relations programs, including digital and television advertising, affiliates and device partners, and social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter to promote its service to potential new members.17

After customers have visited a Web site, the retailer can use explicit opt-in marketing to help sustain relationships with the customer. Opt-in marketing involves the customer giving permission for the retailer to send marketing materials, which leads to higher receptivity to marketing messages. Astute marketers collect preference information, so that content and promotional offers in an E-mail newsletter are relevant to the customer. This leads to an ongoing, evolving relationship between the retailer and the customer.18

TIMING OF THE PROMOTIONAL MIX Reach refers to the number of distinct people exposed to a retailer’s promotion efforts in a specific period. Frequency is the average number of times each person reached is exposed to a retailer’s promotion efforts in a specific period. A retailer can advertise extensively or intensively. Extensive media coverage often means ads reach many people but with relatively low frequency. Intensive media coverage generally means ads are placed in selected media and repeated frequently. Repetition is important, particularly for a retailer seeking to develop an image or sell new goods or services.

Decisions are needed about how to address peak selling seasons and whether to mass or distribute efforts. In peak seasons, all elements of the promotional mix are usually utilized; in slow periods, promotional efforts are often reduced. A massed promotion effort is used by retailers, such as toy retailers, that promote seasonally. A distributed promotion effort is used by retailers, such as fast-food restaurants, that promote throughout the year. Although they are not affected by seasonality in the same way as other retailers, massed advertising is practiced by supermarkets; many use Wednesday or Thursday for weekly newspaper ads. This takes advantage of the fact that a high proportion of consumers make their major shopping trip on Friday, Saturday, or Sunday.

Sales force size can vary by time (morning versus evening), day (weekdays versus weekends), and month (December versus January). Sales promotions also vary in their timing. Store openings and holidays are especially good times for sales promotions (and public relations).

CONTENT OF MESSAGES Whether written or spoken, personally or impersonally delivered, message content is important. Advertising themes, wording, headlines, use of color, size, layout, and placement must be selected. Publicity releases must be written. In personal selling, the greeting, sales presentation, demonstration, and closing need to be applied. With sales promotion, the firm’s message must be composed and placed on the promotional device.

To a large extent, the characteristics of the promotional form influence the message. A shopping bag often contains no more than a retailer’s name, and a billboard (seen at 55 miles per hour) is good for visual effect but can hold only limited information. Yet, a salesperson may be able to hold a customer’s attention for a while. A number of shopping centers use a glossy magazine—in print and online—to communicate a community-oriented image, introduce new stores to consumers, and promote the goods and services carried at stores in the center. Cluttered ads displaying many products suggest a discounter’s orientation, whereas fine pencil drawings and selective product displays suggest a specialty store focus.

Some retailers use comparative advertising to contrast their offerings with those of their competitors. These ads help position a retailer relative to competitors, increase awareness of the firm, maximize the efficiency of a limited budget, and offer credibility. Yet, they provide visibility for competitors, may confuse people, and may lead to legal action. Fast-food and off-price retailers are among those using comparative ads.

MAKEUP OF SALES FORCE Qualifications of sales personnel must be detailed, and these personnel must be recruited, selected, trained, compensated, supervised, and monitored. Personnel should also be classified as order takers or order getters and assigned to the appropriate departments.

SALES PROMOTION TOOLS Specific sales promotion tools must be chosen from among those that were cited in Figure 19-9. The combination of tools depends on short-term goals and the other aspects of the promotion mix. If possible, cooperative ventures should be sought. Tools inconsistent with the firm’s image should never be used; and retailers should recognize the types of promotions that customers really want.

RESPONSIBILITY FOR COORDINATION Regardless of the retailer’s size or format, someone must be responsible for the promotion function. Larger retailers often assign this job to a vice-president who oversees display personnel, works with the firm’s ad agency, supervises the firm’s advertising department (if there is one), and supplies branch outlets with POP materials. In a large retail store, personal selling is usually under the jurisdiction of the store manager. For a promotional strategy to succeed, its components have to be coordinated with other retail mix elements. Sales personnel must be informed of special sales and know product attributes; featured items must be received, marked, and displayed; and accounting entries must be made. Often, a shopping center or a shopping district runs theme promotions, such as “Back to School.” In those instances, someone must coordinate the activities of all participating retailers.

5. Reviewing and Revising the Promotional Plan

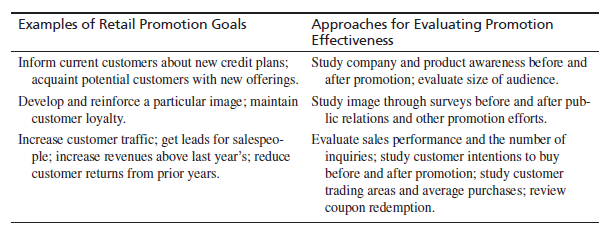

An analysis of the success of a promotional plan depends on its objectives. Revisions should be made if pre-set goals are not achieved. Here are some ways to test the effectiveness of a promotional effort:

Although it may at times be tough to assess promotion efforts (e.g., increased revenues might be due to several factors, not just promotion), it is crucial for retailers to systematically study and adapt their promotional mixes. Walmart provides suppliers with store-by-store data and sets upfront goals for cooperative promotion programs. Actual sales are then compared against the goals. Lowe’s, the home center chain, applies computerized testing to review thousands of different ideas affecting the design of circulars and media mix options. In a suburb of Minneapolis, Supervalu runs a “lab store,” a model store not open to the public where the company can test how new products look on its shelves and experiment with seasonal displays. Retailers such as Kohl’s are testing the effectiveness of newspaper circulars versus digital flyers on in-store sales and profitability.19

Although it may at times be tough to assess promotion efforts (e.g., increased revenues might be due to several factors, not just promotion), it is crucial for retailers to systematically study and adapt their promotional mixes. Walmart provides suppliers with store-by-store data and sets upfront goals for cooperative promotion programs. Actual sales are then compared against the goals. Lowe’s, the home center chain, applies computerized testing to review thousands of different ideas affecting the design of circulars and media mix options. In a suburb of Minneapolis, Supervalu runs a “lab store,” a model store not open to the public where the company can test how new products look on its shelves and experiment with seasonal displays. Retailers such as Kohl’s are testing the effectiveness of newspaper circulars versus digital flyers on in-store sales and profitability.19

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Great – I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your web site. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs as well as related information ended up being truly simple to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or anything, site theme . a tones way for your customer to communicate. Excellent task.