By the early 1960s, the large professionally managed corporation was such a familiar part of the institutional landscape that it began to influence the thinking of economists about the firm. A series of ‘managerial’ models of the firm appeared during these years. They all had the same essential structure. Surpluses could be generated within the large firm. These were interpreted as resulting from the exploitation of a degree of monopoly power rather than of entrepreneurial talents. The firms were under the ‘control’ of the managers but these managers faced constraints on their behaviour. Thus the managerial tradition in the theory of the firm was capable of generating an enormous variety of models depending upon the objectives assumed of the managers and the way the constraints on their behaviour were handled.

The most celebrated managerial models are those of Baumol (1959), Marris (1964) and Williamson (1964). They are distinguished primarily by the assumed objectives of the managers. Baumol suggested that managers maximise revenue from sales, Marris that they maximise growth, and Williamson that they maximise a utility function including ‘staff5 or ‘emoluments’. In each case, the existence of monitoring from outside and limits to managerial discretion were recognised. Baumol included a minimum profit constraint in his model, and Marris similarly incorporated a valuation ratio constraint to reflect pressure from shareholders. The valuation ratio is the market value of outstanding equity shares divided by the book value of the assets of a firm. Too low a valuation ratio will involve a risk of takeover ‘unacceptable’ to the management (Marris, 1963, p.205).

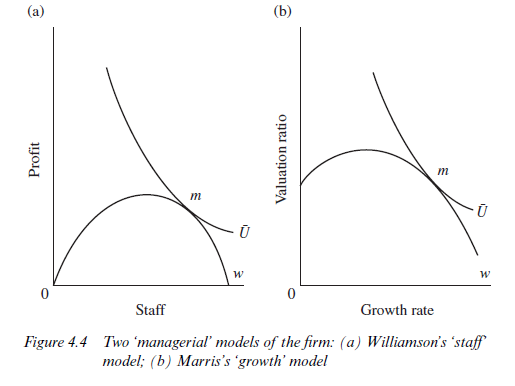

In general, the conclusion of these models was that managerial firms would produce higher output, employ more staff, or grow faster than stockholder-controlled ones. In other words, the costs to the stockholders of asserting their influence gave a margin of discretion to managers which they were assumed to use in pursuit of whatever objectives the analyst felt could plausibly be imputed to them. Figure 4.4 provides a diagrammatic representation of Williamson’s staff model and Marris’s growth model. In the case of part (a), the recruitment of more staff is assumed first to add to profit but after a point to cause profits to decline. The manager’s utility is maximised at point m to the right of the profit-maximising level of staff. For Marris, the figure (part (b)) is again basically the same, with the horizontal axis now measuring the rate of growth and the vertical axis the valuation ratio. The constraint will not emanate from the origin but is expected to have the same concave shape. If growth is pushed past a certain point the value of shares on the market will fall as diseconomies associated with staff training are encountered (Penrose effects21) and as a greater proportion of earnings are retained in the firm to finance expansion instead of being paid in dividends to shareholders.

Later in the 1960s and 1970s, the development of property rights theory and recognition of the importance of ‘studying the property aspect of behaviour’ led to the extension of managerial models into different institutional contexts. Niskanen (1968) introduced the property rights approach to the study of bureaucracy, Furubotn and Pejovich (1970, 1971 and 1974) analysed the labour-managed firm and the Soviet firm within a property rights framework. In Chapters 10 and 11, some of this literature is reviewed in more detail. At the most general level, however, the managerial tradition, while recognising that moral hazard problems were important in particular circumstances, did not directly address the question of the mechanisms which might be used to overcome them. Implicitly, the whole approach was concerned with the problem of the principal-agent relationship. Contractual and monitoring responses were not investigated in detail in the managerial tradition. Chapters 8 and 9 of this book are concerned with the modern analysis of the corporation from a principal-agent perspective.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

I loved as much as you’ll receive carried out right here. The sketch is attractive, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an impatience over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come further formerly again as exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this increase.

I’m still learning from you, while I’m improving myself. I absolutely liked reading all that is written on your site.Keep the posts coming. I liked it!