The next issue of concern to managers is designing the team for greatest effectiveness. One factor is team characteristics, which can affect team dynamics and performance. Character- istics of particular concern are team size, diversity, and member roles.

1. SIZE

More than 30 years ago, psychologist Ivan Steiner examined what happened each time the size of a team increased, and he proposed that team performance and productivity peaked at about five—a quite small number. He found that adding additional members beyond five caused a decrease in motivation, an increase in coordination problems, and a general decline in performance.43 Since then, numerous studies have found that smaller teams perform better, although most researchers say it’s impossible to specify an optimal team size.

One recent investigation of team size based on data from 58 software development teams found that the five best-performing teams ranged in size from 3 to 6 members.44 Re- sults of a recent Gallup poll in the United States show that 82 percent of employees agree that small teams are more productive.45

Teams need to be large enough to incorporate the diverse skills needed to complete a task, enable members to express good and bad feelings, and aggressively solve problems. However, they should also be small enough to permit members to feel an intimate part of the team and to communicate effectively and efficiently. In general, as a team increases in size, it becomes harder for each member to interact with and influence the others.

A summary of research on group size suggests the following:46

- Small teams (two to five members) show more agreement, ask more questions, and ex- change more opinions. Members want to get along with one another. Small teams report more satisfaction and enter into more personal discussions. They tend to be informal and make few demands on team leaders.

- Large teams (10 or more) tend to have more disagreements and differences of opinion. Subgroups often form, and conflicts among them occur. Communication becomes more difficult, and demands on leaders are greater because of the need for stronger coordina- tion, more centralized decision making, and less member participation. Large teams also tend to be less friendly. Turnover and absenteeism are higher in a large team, especially for blue-collar workers. Because less satisfaction is associated with specialized tasks and poor communication, team members have fewer opportunities to participate and feel like an important part of the team.

- As teams increase in size, so does the number of free riders. The term free rider refers to a team member who attains benefits from team membership but does not actively par- ticipate in and contribute to the team’s work. The problem of free riding has likely been experienced by people in student project groups, where some students put more effort into the group project, but everyone benefits from the result. Free riding is sometimes called social loafing because members do not exert equal 47 A classic experiment by German psychologist Ringelmann found that the pull exerted on a rope was greater by individuals working alone than by individuals in a group.48 Similarly, experiments have found that when people are asked to clap and make noise, they make more noise on a per-person basis when working alone or in small groups than they do in a large group.49

As a general rule, large teams make need satisfaction for individuals more difficult; thus, people feel less motivation to remain committed to their goals. Large projects can be split into components and assigned to several smaller teams to keep the benefits of small team size. At Amazon.com, CEO Jeff Bezos established a “two-pizza rule.” If a team gets so large that members can’t be fed with two pizzas, it needs to be split into smaller teams.50

2. DIVERSITY

Because teams require a variety of skills, knowledge, and experience, it seems likely that heterogeneous teams would be more effective than homogeneous ones. In gen- eral, research supports this idea, showing that diverse teams produce more innova- tive solutions to problems.51 Diversity in terms of functional area and skills, think- ing styles, and personal characteristics is often a source of creativity. In addition, diversity may contribute to a healthy level of disagreement that leads to better deci- sion making. At Southern Company, a new CIO made a conscious effort to build a diverse senior leadership team, recruit- ing people to build in gender, racial, edu- cational, religious, cultural, and geograph- ical diversity. “The differences we bring to the table sometimes mean we have long, heated discussions,” says Becky Blalock.

“But once we make a decision, we know we’ve viewed the problem from every possible angle.”52

Research studies have confirmed that both functional diversity and gender diversity can have a positive impact on work team performance.53 Racial, national, and ethnic diversity can also be good for teams, but in the short term, these differences might hinder team in- teraction and performance. Teams made up of racially and culturally diverse members tend to have more difficulty learning to work well together, but with effective leadership, the problems fade over time.54

3. MEMBER ROLES

For a team to be successful over the long run, it must be structured to both maintain its members’ social well-being and accomplish its task. In successful teams, the requirements for task performance and social satisfaction are met by the emergence of two types of roles: task specialist and socioemotional.55

People who play the task specialist role spend time and energy helping the team reach its goal. They often display the following behaviors:

- Initiate ideas. Propose new solutions to team problems.

- Give opinions. Offer opinions on task solutions; give candid feedback on others’ suggestions.

- Seek information. Ask for task-relevant facts.

- Summarize. Relate various ideas to the problem at hand; pull ideas together into a sum- mary perspective.

- Energize. Stimulate the team into action when interest drops.56

People who adopt a socioemotional role support team members’ emotional needs and help strengthen the social entity. They display the following behaviors:

- Encourage. Are warm and receptive to others’ ideas; praise and encourage others to draw forth their contributions.

- Harmonize. Reconcile group conflicts; help disagreeing parties reach agreement.

- Reduce tension. Tell jokes or in other ways draw off emotions when group atmosphere is tense.

- Follow. Go along with the team; agree to other team members’ ideas.

- Compromise. Will shift own opinions to maintain team harmony.57

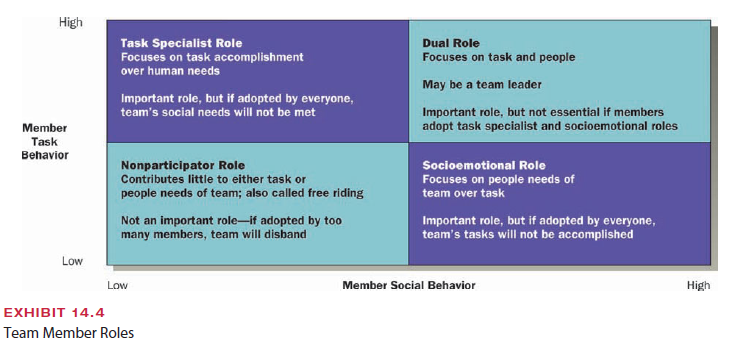

Exhibit 14.4 illustrates task specialist and socioemotional roles in teams. When most individuals in a team play a social role, the team is socially oriented. Members do not criti- cize or disagree with one another and do not forcefully offer opinions or try to accomplish team tasks because their primary interest is to keep the team happy. Teams with mostly socioemotional roles can be satisfying, but they also can be unproductive. At the other extreme, a team made up primarily of task specialists will tend to have a singular concern for task accomplishment. This team will be effective for a short period of time but will not be satisfying for members over the long run. Task specialists convey little emotional con- cern for one another, are unsupportive, and ignore team members’ social and emotional needs. The task-oriented team can be humorless and unsatisfying.

As Exhibit 14.4 illustrates, some team members may play a dual role. People with dual roles both contribute to the task and meet members’ emotional needs. Such people often become team leaders. A study of new-product development teams in high-technology firms found that the most effective teams were headed by leaders who balanced the technical needs of the project with human interaction issues, thus meeting both task and socioemotional needs.58 Exhibit 14.4 also shows the final type of role, called the nonparticipator role, in which people contribute little to either the task or the social needs of team members. These people are free riders, as defined earlier and typically are held in low esteem by the team.

The important thing for managers to remember is that effective teams must have people in both task specialist and socioemotional roles. Humor and social concern are as impor- tant to team effectiveness as are facts and problem solving. Managers also should remem- ber that some people perform better in one type of role; some are inclined toward social concerns and others toward task concerns. A well-balanced team will do best over the long term because it will be personally satisfying for team members as well as permit the accom- plishment of team tasks.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

hi!,I love your writing so a lot! proportion we communicate more about your article on AOL?

I need a specialist in this space to unravel my problem. Maybe

that is you! Looking forward to look you.

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thx again