1. Text and images

This discursive introduction in what is intended to be a practical book is because of the need to draw back from the apparent obviousness of visual ‘reality’ expressed in the opening paragraphs.

That caution is not intended to devalue visual representation: on the contrary, why not use images to ‘describe’? The question is pertinent because most observational studies, even those which deal with an unfamiliar culture or sub-culture, do so almost exclusively in text, an apparently unquestioned practice up to the 1990s.

There are reasons for this omission, apart from an unquestioned convention and the matter of cost – less of an issue now thanks to the digital revolution. These caveats need reflection:

- photography can make ‘observation’ more intrusive (and more obvious)

- people may object to being photographed

- photography may infringe anonymity

- photography may affect the behaviour of those being observed.

These may be seen as problems of research procedure – of the use of photography in the practice of data collection. Putting those issues (partly ethical) to one side for the moment we can turn attention to the different qualities of data in the form of text as against images.

2. Distinctive characteristics

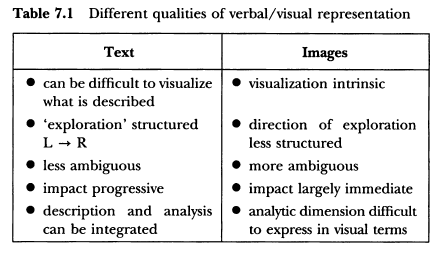

A simple listing of these in tabular form might be as shown in Table 7.1.

The first and last contrasts here are perhaps those which polarize the media most emphatically.

The old saying that ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ is false – they are not equivalent in any ratio. Words may evoke but they do not shorn point one. Point two is that language can be, commonly is, intrinsically more abstract, more analytic, than visual depiction. So the issue is one of recognizing what the different media do best in the research area we are dealing with. As Pink puts it:

Visual research methods are not purely visual. Rather they pay particular attention to visual aspects of culture. Similarly, they cannot be used independently of other methods; neither a purely visual ethnography nor an exclusively visual approach to culture can exist. (Pink, 2007, p. 21.)

This is not just an argument for what is best expressed in visual terms but also for ‘a shift from word-and-sentence- based anthropological thought to image-and-sequence- based anthropological thought’ (MacDougall, 1997, p. 292, cited in Pink, ibid., p.ll). In other words, a shift in emphasis is required to those visual dimensions of culture that have often been omitted and which constitute a particular form of knowledge. How then is this material to be represented and interpreted?

3. Images and meaning

Traditionally in the research literature, where they have been used at all, photographs (and film/video) have been treated as ‘illustrations’ to enhance text. Two elements have been neglected:

- The ‘reading’ of photographs – the elements of meaning they convey and how they relate to each other (like words and syntax in text).

- The extent to which an extended narrative account or ‘argument’ can be presented in a sequence of still photographs: a more comprehensive account (as in extended text) made up of the ‘sentences’ contained in a single photograph.

Reading photographs

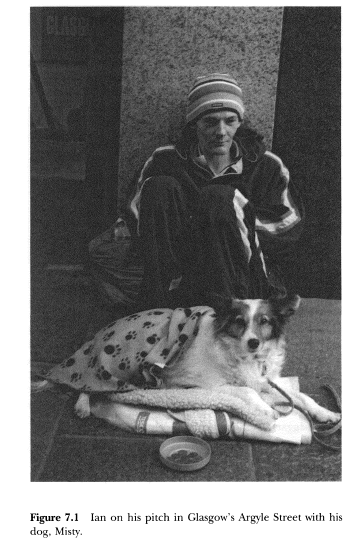

Take as an example the photograph of Ian, the Glasgow street beggar, described in the previous chapter (see p. 72).

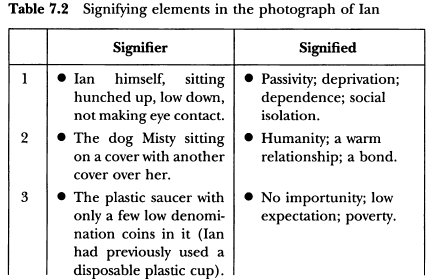

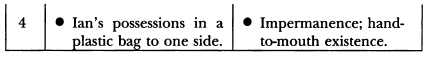

At the time of writing this is the only kind of photograph I have taken of him. What are the ‘signifiers’ – elements that communicate meaning – it contains? Considering this question alerts you to the particular properties of still photographs in observational research.

First, although you get an immediate impression from a photograph, you don’t ‘see it all at once’. We know this in relatively objective terms from research on visual perception. Using a special camera that records eye movements and fixations, it is clear that the eye inspects a display in a succession of saccades: sweeping movements between brief stationary fixations. That is, the eye ‘reads’ the display in a sequential manner. Something very similar, but in a more regulated fashion, occurs in the reading of text. But in both cases the extraction of meaning takes place in the mind of the reader, and it will be constructed to some extent differently from one person to another.

What signifiers can you see in Ian’s photograph? And what meanings do you derive from it? Here is my own list of the main elements (Table 7.2).

Note that both the identification of signifiers and even more the signified (attributed meaning) is a matter of choice. Nor is there any implication that Ian has consciously thought through, in any analytic fashion, the elements of his appeal. But, to take point (1): had Ian been sitting on a chair, or even a cushion, the appeal would have been lessened; as it is he is sitting on the cold, hard pavement. Point (2) there is (to me) no suggestion of artifice in the presence of Ian’s dog, even though it is commonplace for street beggars; but without it the appeal would certainly be less. Point (3): the throw-away plastic saucer (or cup) itself has layers of meaning; consider the difference a collecting box would make (and the meanings that would connote). And point (4) a neat rucksack (or even a very shabby one) would connote different qualities/meanings from the disposable plastic bag.

Now all of these interpretations are my constructions: meaning is always an attribute. There might well be agreement, perhaps negotiated, between different people. But to return in this practical example to themes discussed earlier, although there is a physically ‘objective’ photograph, interpretations of it are necessarily subjective. These ‘interpretations’ are part of research data, and differing judgements can be compared including one’s own changed judgements over time. I see Ian differently now from my first impression of someone passive and pathetic. Note that this whole issue is quite different from the positivist psychometric notion of reliability (a technical term relating to the consistency of observations or test scores) and which implies that there is a true reality and that observers/interpreters are flawed instruments in the recording of it.

Every picture tells a story

But it has to be read – as demonstrated above. A photograph with its signified elements is not like a list of isolated words: these elements are part of a (visually) structured relationship. We have used words to demonstrate it in this instance, but what is required is a more analytic approach to reading images; to repeat the point, you don’t just ‘see’ them. The need is to establish (non-constraining) conventions for reading visual observational material so that the contribution of these kinds of data is given fuller recognition.

The challenge for the researcher is well expressed by Pink (2007, p. 6) when she writes:

This means abandoning the possibility of a purely objective social science and rejecting the idea that the written word is essentially a superior medium of ethnographic representation. While images should not necessarily replace words as the dominant mode of research or representation, they should be regarded as an equally meaningful element of ethnographic work (emphasis added).

But this kind of call to action is no more than rhetoric unless it can be translated into the detail of practice.

Source: Gillham Bill (2008), Observation Techniques: Structured to Unstructured, Continuum; Illustrated edition.

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021