Once a company decides on its target market, establishes a position within that market, and establishes a brand, it is ready to begin planning the details of its marketing mix. A firm’s marketing mix is the set of controllable, tacti- cal marketing tools that it uses to produce the response it wants in the target market.18 Most marketers organize their marketing mix into four categories: product, price, promotion, and place (or distribution). For an obvious reason, these categories are commonly referred to as the 4Ps.

The way a firm sells and distributes its product dramatically affects a company’s marketing program. This effect means that the first decision a firm has to make is its overall approach to selling its product or service. Even for similar firms, the marketing mix can vary significantly, depending on the way the firms do business. For example, a software firm can sell directly through its website or through retail stores, or it can license its product to another company to be sold under that company’s brand name. A start-up that plans to sell directly to the public would set up its promotions program in a much different way than a firm planning to license its products to other firms. A firm’s marketing program should be consistent with its business model and its overall business plan.

Let’s look more closely at the 4Ps. Again, these are broad topics on which entire books have been written. In this section, we focus on the aspects of the 4Ps that are most relevant to entrepreneurial ventures.

1. Product

A firm’s product, in the context of its marketing mix, is the good or service it offers to its target market. Technically, a product is something that takes on physical form, such as an Apple iPhone, a bicycle, or a solar panel. A service is an activity or benefit that is intangible and does not take on a physical form, such as an airplane trip or advice from an attorney. But when discussing a firm’s marketing mix, both products and services are lumped together under the label “product.”

Determining the product or products to be sold is central to the firm’s en- tire marketing effort. As stressed throughout this book, the most important attribute of a product is that it adds value in the minds of its target customers. Let’s think about this by comparing vitamins with pain pills, as articulated by Henry W. Chesbrough, a professor at Harvard University:

We all know that vitamins are good for us and that we should take them. Most of us, though, do not take vitamins on a regular basis, and whatever benefits vita- mins provide do not seem to be greatly missed in the short term. People therefore pay relatively very little for vitamins. In contrast, people know when they need a pain killer. And they know they need it now, not later. They can also tell quite read- ily whether the reliever is working. People will be willing to pay a great deal more for a pain reliever than they pay for a vitamin. In this context, the pain reliever pro- vides a much stronger value proposition than does a vitamin—because the need is felt more acutely, the benefit is greater and is perceived much more quickly.19

This example illustrates at least in part why investors prefer to fund firms that potentially have breakthrough products, such as a software firm that is working on a product to eliminate e-mail spam or a biotech firm that is work- ing on a cure for a disease. These products are pain pills rather than vitamins because their benefits would be felt intensely and quickly. In contrast, a new restaurant start-up or a new retail store may be exciting, but these types of firms are more akin to a vitamin than a pain pill. The benefits of these busi- nesses would not be felt as intensely.

As the firm prepares to sell its product, an important distinction should be made between the core product and the actual product. While the core prod- uct may be a CD that contains a tax preparation program, the actual product, which is what the customer buys, may have as many as five characteristics: a quality level, features, design, a brand name, and packaging.20 For example, TurboTax is an actual product. Its name, features, warranty, ability to upgrade, packaging, and other attributes have all been carefully combined to deliver the benefits of the product: helping people prepare their federal and state tax returns while receiving the biggest refund possible. When first introducing a product to the market, an entrepreneur needs to make sure that more than the core product is right. Attention also needs to be paid to the actual product—the features, design, packaging, and so on that constitute the collection of benefits that the customer ultimately buys. Anyone who has ever tried to remove a prod- uct from a frustratingly rigid plastic container knows that the way a product is packaged is part of the product itself. The quality of the product should not be compromised by missteps in other areas.

The initial rollout is one of the most critical times in the marketing of a new product. All new firms face the challenge that they are unknown and that it takes a leap of faith for their first customers to buy their products. Some start- ups meet this challenge by using reference accounts. A reference account is an early user of a firm’s product who is willing to give a testimonial regarding his or her experience with the product. For example, imagine the effect of a spokesperson for Apple Inc. saying that Apple used a new computer hardware firm’s products and was pleased with their performance. A testimonial such as this would pave the way for the sales force of this new firm’s hardware, and the new firm could use it to reduce fears that it was selling an untested and perhaps ineffective product.

To obtain reference accounts, new firms must often offer their product to an initial group of customers for free or at a reduced price in exchange for their willingness to try the product and for their feedback. There is nothing improper about this process as long as everything is kept aboveboard and the entrepre- neur is not indirectly “paying” someone to offer a positive endorsement. Still, many entrepreneurs are reluctant to give away products, even in exchange for a potential endorsement. But there are several advantages to getting a strong set of endorsements: credibility with peers, non-company advocates who are willing to talk to the press, and quotes or examples to use in company bro- chures and advertisements.

2. Price

Price is the amount of money consumers pay to buy a product. It is the only element in the marketing mix that produces revenue; all other elements rep- resent costs.21 Price is an extremely important element of the marketing mix because it ultimately determines how much money a company can earn. The price a company charges for its products also sends a clear message to its target market. For example, Oakley positions its sunglasses as innovative, state-of-the art products that are both high quality and visually appealing. This position in the market suggests the premium price that Oakley charges. If Oakley tried to establish the position described previously and charged a low price for its products, it would send confusing signals to its customers. Its cus- tomers would wonder, “Are Oakley sunglasses high quality or aren’t they?” In addition, the lower price wouldn’t generate the sales revenue Oakley requires to continuously differentiate its sunglasses from competitors’ products in ways that create value for customers.

Most entrepreneurs use one of two methods to set the price for their prod- ucts: cost-based pricing or value-based pricing.

Cost-based Pricing In cost-based pricing, the list price is determined by adding a markup percentage to a product’s cost. The markup percentage may be standard for the industry or may be arbitrarily determined by the en- trepreneur. The advantage of this method is that it is straightforward, and it is relatively easy to justify the price of a good or service. The disadvantage is that it is not always easy to estimate what the costs of a product will be. Once a price is set, it is difficult to raise it, even if a company’s costs increase in an unpredicted manner. In addition, cost-based pricing is based on what a com- pany thinks it should receive rather than on what the market thinks a good or service is worth. It is becoming increasingly difficult for companies to dictate prices to their customers, given customers’ ability to comparison shop on the Internet to find what they believe is the best bargain for them.22

Value-based Pricing In value-based pricing, the list price is deter – mined by estimating what consumers are willing to pay for a product and then backing off a bit to provide a cushion. What a customer is willing to pay is determined by the perceived value of the product and by the number of choices available in the marketplace. Sometimes, to make this determi- nation, a company has to work backwards by testing to see what its target market is willing to pay. A firm influences its customers’ perception of the value through positioning, branding, and the other elements of the market- ing mix. Most experts recommend value-based pricing because it hinges on the perceived value of a product or service rather than cost plus markup, which, as stated previously, is a formula that ignores the customer.23 A gross margin (a company’s net sales minus its costs of goods sold) of 60 to 80 percent is not uncommon in high-tech industries. An Intel chip that sells for $300 may cost $50 to $60 to produce. This type of markup reflects the perceived value of the chip. If Intel used a cost-based pricing method instead of a value-based approach, it would probably charge much less for its chips and earn less profit.

Most experts also warn entrepreneurs to resist the temptation to charge a low price for their products in the hopes of capturing market share. This ap- proach can win a sale but generates little profit. In addition, most consumers make a price-quality attribution when looking at the price of a product. This means that consumers naturally assume that the higher-priced product is also the better-quality product.24 If a firm charges a low price for its products, it sends a signal to its customers that the product is low quality regardless of whether it really is.

A vivid example of the association between price and quality is provided by SmugMug (www.smugmug.com), an online photo-sharing site that charges a $40-per-year base subscription fee. According to its website, the company has “Billions of Happy Photos” and “Millions of Happy Customers.” What’s interesting about the company is that most of its competitors, including Photobucket, Flicker, and Picas Web Albums, offer a similar service for free. Ostensibly, the reason SmugMug is able to charge a fee is that it offers higher levels of customer service and has a more user-friendly interface (in terms of how you view your photos online) than its competitors. But the owners of SmugMug feel that its ability to charge goes beyond these obvious points. Some of the free sites have closed abruptly, and their users have lost photos. SmugMug, because it charges, is seen as more reliable and dependable for the long term. (Who wants to lose their photos?) In addition, the owners believe that when people pay for something, they innately assign a higher value to it. As a result, SmugMug users tend to treat the site with respect, by posting at- tractive, high-quality photos that are in good taste. SmugMug’s users appreci- ate this facet of the site, compared to the free sites, where unseemly photos often creep in.25

The overarching point of this example is that the price a company is able to charge is largely a function of (1) the objective quality of a product or service and (2) the perception of value that is created in the minds of customers rela- tive to competing products in the marketplace. These are issues a firm should consider when developing its positioning and branding strategies.

Price is such an important element of the marketing mix that, if a company gets it wrong, it can be extremely damaging to both the company’s short-term profits and future viability. The “What Went Wrong?” feature in this chapter focuses on marketing missteps at JCPenney. In 2011–2012, JCPenney, under the leadership of CEO Ron Johnson, made critical mistakes in the areas of branding, testing (or the lack thereof), and pricing. The mistakes provide les- sons for start-ups of marketing miscues they should be particularly on guard to avoid in their own situations.

3. Promotion

Promotion refers to the activities the firm takes to communicate the merits of its product to its target market. Ultimately, the goal of these activities is to per- suade people to buy the product. There are a number of these activities, but most start-ups have limited resources, meaning that they must carefully study promotion activities before choosing the one or ones they’ll use. Let’s look at the most common activities entrepreneurs use to promote their products.

Advertising Advertising is making people aware of a product in hopes of persuading them to buy it. Advertising’s major goals are to:

■ Raise customer awareness of a product

■ Explain a product’s comparative features and benefits

■ Create associations between a product and a certain lifestyle

These goals can be accomplished through a number of media including direct mail, magazines, newspapers, radio, the Internet, blogs, television, and billboard advertising. The most effective ads tend to be those that are memorable and support a product’s brand. However, advertising has some major weaknesses, including the following:

■ Low credibility

■ The possibility that a high percentage of the people who see the ad will not be interested

■ Message clutter (meaning that after hearing or reading so many ads, peo- ple simply tune out)

■ Relative costliness compared to other forms of promotions

■ The perception that advertising is intrusive26

Because of these weaknesses, most start-ups do not advertise their prod- ucts broadly. Instead, they tend to be very frugal and selective in their advertis- ing efforts or engage in hybrid promotional campaigns that aren’t advertising per se, but are designed to promote a product or service.

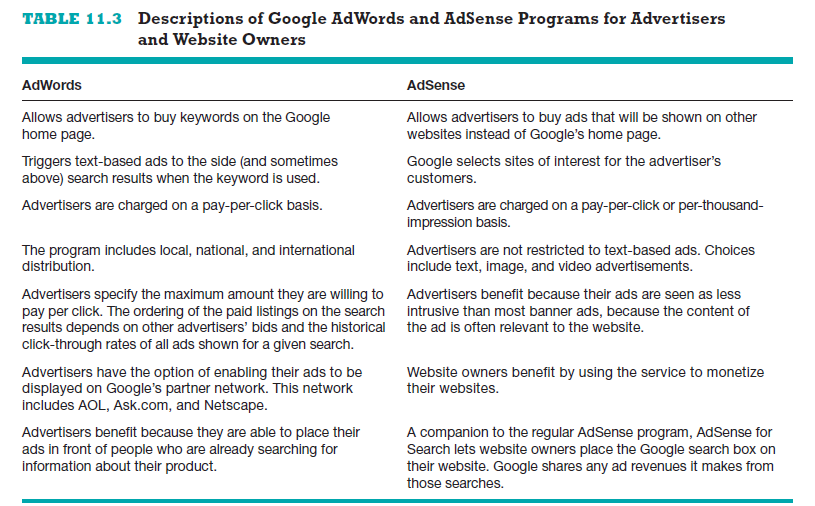

Along with engaging in hybrid promotional campaigns, many start-ups advertise in trade journals or utilize highly focused pay-per-click advertising provided by Google, Bing, or another online firm to economize the advertising dollars. Pay-per-click advertising represents a major innovation in advertising and has been embraced by firms of all sizes. Google has two pay-per-click pro- grams—AdWords and AdSense. AdWords allows an advertiser to buy keywords on Google’s home page (www.google.com), which triggers text-based ads to the side (and sometimes above) the search results when the keyword is used. So, if you type “soccer ball” into the Google search bar, you will see ads that have been paid for by companies that have soccer balls to sell. Many advertisers report impressive results utilizing this approach, presumably because they are able to place their ads in front of people who are already searching for in- formation about their product. Google’s other pay-per-click program is called AdSense. It is similar to AdWords, except the advertiser’s ads appear on other websites instead of Google’s home page. For example, an organization that pro- motes soccer might allow Google to place some of its client’s ads on its website. The advertiser pays on a pay-for-click basis when its ad is clicked on the soccer organization’s site. Google shares the revenue generated by the advertisers with the sponsoring site. Table 11.3 provides a summary of the Google AdWords and Google AdSense programs. Yahoo and Microsoft’s joint program, which is very similar to Google’s, is called the Yahoo Bing Network. The Yahoo Bing Network is a joint venture between Yahoo and Microsoft to sell pay-per-click ads on both the Yahoo and the Microsoft Bing search engines.

As an aside, online advertising in general allows people who know a lot about a particular topic to launch a website, populate it with articles, tips, videos, and other useful information, and make money online by essentially selling access to the people attracted to the website. For example, Tim Carter, a well-known columnist on home repair, has a website named Ask the Builder (www.askthebuilder.com). Information and instructions on all types of home building projects and repair are available on this website, as are links to areas that focus on specific topics, such as air-conditioning, cabinets, deck con- struction, and plumbing. Clicking any one of these areas brings up online ads that deal with that specific area. All together, the site has hundreds of ads. Carter is able to do this and still attract large numbers of visitors because the information he provides is good and helpful. He might also believe that his ads, in a certain respect, add valuable content to the site. If someone is looking at the portion of his site that deals with how to construct a deck, he or she might actually appreciate seeing ads that point to websites where books and blue- prints for building decks are available.

Another medium for advertising, which is growing in popularity, is social media sites, such as Facebook. The advantage of Facebook, in particular, is that it allows companies to deliver highly targeted ads based on where people live and how they describe themselves on their Facebook profiles. For example, a company that sells licensed sports apparel for the Boston Red Sox can deliver a highly targeted ad to the people most likely to buy its products. The company could deliver ads exclusively to men who live in Massachusetts and cite the Boston Red Sox in their Facebook profiles. Any company can identify its ideal potential customer and deliver targeted Facebook ads in the same manner.

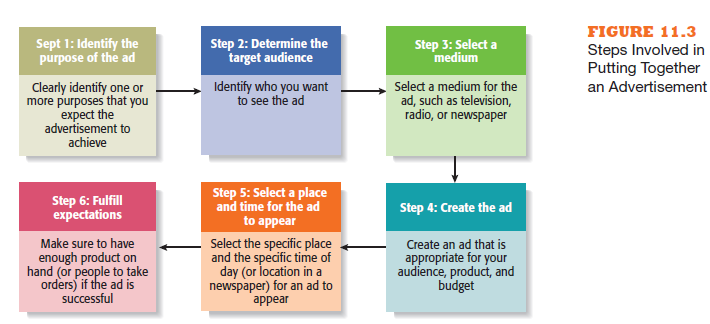

The steps involved in putting together an advertisement are shown in Figure 11.3. Typically, for start-up firms, advertisements are the most effective if they’re part of a coordinated marketing campaign.27 For example, a print ad might feature a product’s benefits and direct the reader to a website or Facebook page for more information. The website or Facebook page might offer access to coupons or other incentives if the visitor fills out an information request form (which asks for name, address, and phone number). The names collected from the information request form could then be used to make sales calls.

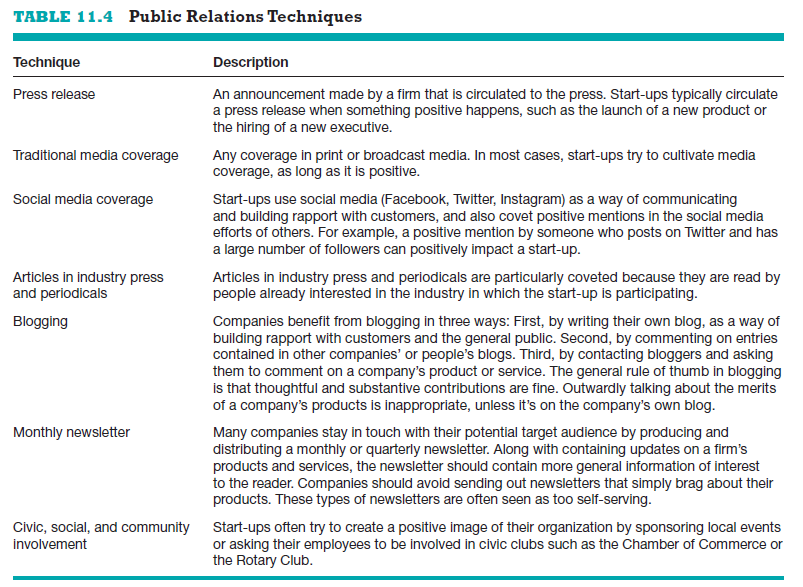

Public relations One of the most cost-effective ways to increase the awareness of the products a company sells is through public relations. Public relations refers to efforts to establish and maintain a company’s image with the public. The major difference between public relations and advertising is that public relations is not paid for directly. The cost of public relations to a firm is the effort it makes to network with journalists, blog authors, and other people to try to interest them in saying or writing good things about the com- pany and its products. Several techniques fit the definition of public relations, as shown in Table 11.4. Airbnb’s campaign to reach out to bloggers, chronicled in the “Savvy Entrepreneurial Firm” feature in this chapter, is an example of a public relations campaign.

Many start-ups emphasize public relations over advertising primarily be- cause it’s cheaper and helps build the firm’s credibility. In slightly different words, it may be better to start with public relations rather than advertising because people view advertising as the self-serving voice of a company that’s anxious to make a sale.28 A firm’s public relations effort can be oriented to tell-ing the company’s story through a third party, such as a magazine or a news- paper. If a magazine along the lines of Inc., Entrepreneur, or Fortune publishes a positive review of a new company’s products, or a company is profiled in a prominent blog, consumers are likely to believe that those products are at least worth a try. They think that because these magazines and blogs have no vested interest in the company, they have no reason to stretch the truth or lie about the usefulness or value of a company’s products. Technology companies, for ex- ample, that are featured on TechCrunch or Mashable, two popular technology blogs, typically see an immediate spike in their Web traffic and sales as a result of the mention.

There are many ways in which a start-up can enhance its chances of getting noticed by the press, a blogger, or someone who is influential in social media. As mentioned earlier, journalists and others are typically not interested in overtly helping a firm promote its product. Instead, what they prefer is a human inter- est story about why a firm was started or a story that focuses on something that is particularly unique about the start-up. The “Savvy Entrepreneurial Firm” feature in this chapter affirms these points. The feature focuses on how Airbnb, which is a marketplace for people to list, discover, and book unique spaces (typically in people’s homes or apartments), used blogs as a stepping- stone to generate substantial buzz about its start-up. Another technique is to prepare a press kit, which is a folder that contains background information about the company and includes a list of its most recent accomplishments. The kit is normally distributed to journalists and made available online. Attending trade shows can also contribute to a firm’s visibility. A trade show is an event at which the goods or services in a specific industry are exhibited and dem- onstrated. Members of the media often attend trade shows to get the latest industry news. For example, the largest trade show for consumer electronics is International CES, which is held in Las Vegas every January. Many companies wait until this show to announce their most exciting new products. They do this in part because they have a captive media audience that is eager to find inter- esting stories to write about. Fitbit’s exhibit at a recent International CES show is pictured in Chapter 5.

Social Media Use of social media consists primarily of blogging and estab- lishing a presence and connecting with customers and others through social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter. Many of the new ventures fea- tured in this book are active users of social media. A good example is ModCloth, the focus of Case 11.1. ModCloth maintains an active blog, has three separate Twitter accounts (one for general product information, one that is more fashion oriented, and one for recruiting), and maintains an energetic Facebook page.

The idea behind blogs is that they familiarize people with a business and help build an emotional bond between a business and its customers. ModCloth’s blog (http://blog.modcloth.com), for example, draws attention to the company’s products, but also posts fun, entertaining, and informative articles, features, and photos of interest to ModCloth’s target market—18- to 32-year-old women.

The blog also features contests that provide cash prizes, posts photos of custom- ers wearing ModCloth products, and provides behind-the-scenes glimpses of what it’s like to work at ModCloth. For example, employees are allowed to bring dogs to work, which are called ModDogs. Periodically, one of the dogs is featured on the blog.

The key to maintaining a successful blog is to keep it fresh and make it informative and fun. It should also engage its readers in the “industry” and “lifestyle” that a company promotes as much as a company’s products. For example, just after Labor Day 2013, ModCloth posted the following on its blog:

If the old rule of not wearing white after Labor Day has you rolling your eyes, you’re not alone. We too believe that fashion rules were meant to be broken, so we set out to find some post-Labor Day inspiration in the form of street style pho- tos, bloggers, and our ever-stylish Style Gallery community members. If you’re on the hunt for the perfect way to mix white into your wardrobe this fall, check out the looks below.29

This is the type of feature that ModCloth customers probably enjoy seeing.

Many start-ups also benefit from establishing a presence on social network- ing sites like Facebook and Twitter. The total number of Facebook accounts is huge, which makes it particularly attractive. Facebook allows anyone in the world that is 13 years old or older to become a registered user. As of September 2012, Facebook had more than one billion active users. The company has also made itself more attractive to businesses since launching a family of so- cial plug-ins in April 2010. Social plug-ins are tools that websites can use to provide their users with personalized and social experiences. Facebook’s most popular social plug-ins, which a website can install, include the Like button, the Share button, and the Comments box. These social plug-ins allow people to share their experiences off Facebook with their friends on Facebook. The Share button, for example, lets users share pages from a company’s website on their Facebook page with one click.30 As a result, a young woman who just bought a dress from ModCloth’s website, because ModCloth has placed the Facebook Share plug-in on its site, can immediately post a picture and description of the dress on her Facebook page and write a comment about the purchase. She might say, “Hey everyone, look at the cool dress I just bought at www.modcloth. com.” This is tantamount to free advertising for ModCloth.

Along with taking advantage of social plug-ins, businesses establish a presence on Facebook and Twitter to build a community around their products and services. The benefits include brand building, engaging customers, and getting lead generation and online sales. In regard to branding, a Facebook page or Twitter account can allow a firm to post or tweet material that’s con- sistent with its brand. For example, Beyond Meat, a company that is produc- ing plant-based substitutes for meat products, such as Chicken-Free Strips (which are made from plant-based proteins but taste just like traditional chicken strips), frequently posts material on Twitter that pertains to nutrition, cooking, healthy recipes, plant-based substitutes for meat products, and so on. By doing this, Beyond Meat establishes itself as an expert on healthy eat- ing and healthy lifestyles.

In regard to engagement, many companies use social networks to strengthen their relationships with customers by soliciting feedback, running contests, or posting fun games that pertain to a company’s product. For example, ModCloth uses Twitter to do several things. First, the firm posts fun facts, polls, and even recipes that they think their customers will like. Second, they encourage ques- tions from customers, and usually provide a response in a matter of minutes. Third, they post photos of the most popular ModCloth apparel and behind-the- scenes photos of ModCloth employees, offices, and events. What they don’t do is overdo promotions. They keep their Twitter account upbeat, fun, and light. In terms of Facebook, ModCloth posts photos and comments about their prod- ucts to spark conversations with customers. For example in late fall, as winter approaches, they might post a photo of warm-weather ModCloth apparel and accessories and ask, “What cold-weather accessories are the most important to you?” They’ll then engage with ModCloth followers, who send in comments just like any Facebook friend would do. ModCloth also makes effective use of Pinterest. Among other things, they post photos of their clothing matched up with accessories and shoes that they sell. It’s a great way to show customers how they can buy ModCloth products and mix and match to create multiple outfits and looks.

There is a potpourri of additional social media outlets from which firms can benefit. For example, many businesses post videos on YouTube. YouTube now offers heavy users the ability to create a YouTube channel to archive their videos and to create their own YouTube site. An example is GoPro’s YouTube channel at www.youtube.com/gopro. Businesses can also establish a presence on niche social networking sites that are consistent with their mission and product offerings. An example is Care2 (www.care2.com), which is an online community that promotes a healthy and green lifestyle and takes action on social causes.

Other Promotion-related activities There are many other activities that help a firm promote and sell its products. Some firms, for example, give away free samples of their products. This technique is used by pharmaceutical companies that give physicians free samples to distribute to their patients as appropriate. A similar technique is to offer free trials, such as a three-month subscription to a magazine or a two-week membership to a fitness club, to try to hook potential customers by exposing them directly to the product or service.

A fairly new technique that has received quite a bit of attention is viral marketing, which facilitates and encourages people to pass along a market- ing message about a particular product. The most well-known example of viral marketing is Hotmail. When Hotmail first started distributing free e-mail accounts, it put a tagline on every message sent out by Hotmail users that read “Get free e-mail with Hotmail.” Within less than a year, the company had several million users. Every e-mail message that passed through the Hotmail system was essentially an advertisement for Hotmail. The success of viral marketing depends on the pass-along rate from person to person. Very few companies have come close to matching Hotmail’s success with viral market- ing. However, the idea of designing a promotional campaign that encourages a firm’s current customers to recommend its product to future customers is well worth considering.

A technique related to both viral marketing and creating buzz is guerrilla marketing. Guerrilla marketing is a low-budget approach to marketing that relies on ingenuity, cleverness, and surprise rather than traditional techniques. The point is to create awareness of a firm and its products, often in uncon- ventional and memorable ways. The term was first coined and defined by Jay Conrad Levinson in the 1984 book Guerrilla Marketing. Guerrilla marketing is particularly suitable for entrepreneurial firms, which are often on a tight budget but have creativity, enthusiasm, and passion to draw from.

4. Place (or Distribution)

Place, or distribution, encompasses all the activities that move a firm’s product from its place of origin to the consumer. A distribution channel is the route a product takes from the place it is made to the customer who is the end user.

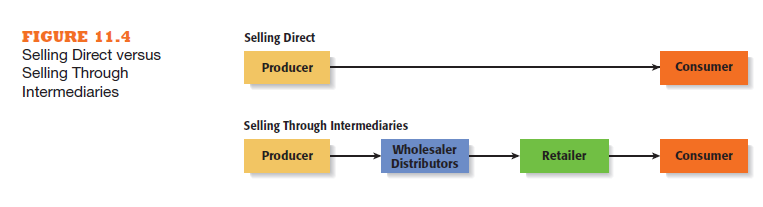

The first choice a firm has to make regarding distribution is whether to sell its products directly to consumers or through intermediaries such as wholesal- ers or distributors. Within most industries, both choices are available, so the decision typically depends on how a firm believes its target market wants to buy its product. For example, it would make sense for a music studio that is targeting the teen market to produce digital recordings and sell the recordings directly over the Web. Most teens have access to a computer or smartphone and know how to download music. In contrast, it wouldn’t make nearly as much sense for a recording company targeting retirees to use the same distribution channel to sell its music offerings. A much smaller percentage of the retiree market knows how to download music from the Web. In this instance, it would make more sense to produce CDs and partner with wholesalers or distributors to place them in retail outlets where retirees shop.

Figure 11.4 shows the difference between selling direct and selling through an intermediary. Let’s look at the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

Selling Direct Many firms sell directly to customers. Being able to con- trol the process of moving their products from their place of origin to the end user instead of relying on third parties is a major advantage of direct selling. Examples of companies that sell direct are Abercrombie & Fitch, which sells its clothing through company-owned stores, and Fitbit, which sells its exercise and sleep monitoring device through its website.

The disadvantage of selling direct is that a firm has more of its capital tied up in fixed assets because it must own or rent retail outlets, must maintain a sales force, and/or must support an e-commerce website. It must also find its own buyers rather than have distributors that are constantly looking for new outlets for the firm’s products.

The advent of the Internet has changed how many companies sell their products. Many firms that once sold their products exclusively through retail stores are now also selling directly online. The process of eliminating layers of middlemen, such as distributors and wholesalers, to sell directly to customers is called disintermediation.

Selling Through intermediaries Firms selling through intermediaries typically pass off their products to wholesalers or distributors that place them in retail outlets to be sold. An advantage of this approach is that the firm does not need to own as much of the distribution channel. For example, if a company makes car speakers and the speakers are sold through retail outlets such as Best Buy and Walmart, the company avoids the cost of building and maintain- ing retail outlets. It can also rely on its wholesalers to manage its relationship with Best Buy and Walmart and to find other retail outlets in which to sell its products. The trick to utilizing this approach is to find wholesalers and distribu- tors that will represent a firm’s products. A start-up must often pitch wholesal- ers and distributors much like it pitches an investor for money in order to win their support and cooperation.

The disadvantage of selling through intermediaries is that a firm loses a certain amount of control of its product. Even if a wholesaler or distributor places a firm’s products with a top-notch retailer like Best Buy or Walmart, there is no guarantee that Best Buy’s or Walmart’s employees will talk up the firm’s products as much as they would if they were employees in the firm’s own stores. Selling via distributors and wholesalers can also be expensive, so it is best to carefully weigh all options. For example, a firm that sells an item for $100 on its website and makes $50 (after expenses) may only make $10 if the exact same item is placed by a distributor into a retail store. The $40 difference represents the profits taken by the distributor and the retailer.

Some firms enter into exclusive distribution arrangements with channel partners. Exclusive distribution arrangements give a retailer or other inter- mediary the exclusive rights to sell a company’s products. The advantage to giving out an exclusive distribution agreement is to motivate a retailer or other intermediary to make a concerted effort to sell a firm’s products without hav- ing to worry about direct competitors. For example, if Nokia granted AT&T the exclusive rights to sell a new type of cell phone, AT&T would be more motivated to advertise and push the phone than if many or all cell phone companies had access to the same phone.

One choice that entrepreneurs are confronted with when selling through intermediaries is how many channels to sell through. The more channels a firm sells through, the faster it can grow. But there are problems associated with selling through multiple channels, particularly early in the life of a firm. A firm can lose control of how its products are being sold. For example, the more retailers through which Ralph Lauren sells its clothing, the more likely it is that one or more retailers will not display the clothes in the manner the company wants.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that Ive truly enjoyed browsing your blog posts. In any case I will be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again soon!

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.