Using case studies for research purposes remains one of the most challenging of all social science endeavors. The purpose of this book is to help you—an experienced or budding social scientist—to deal with the challenge. Your goal is to design good case studies and to collect, present, and analyze data fairly. A further goal is to bring the case study to closure by writing a compelling report or book.

Do not underestimate the depth of your challenge. Although you may be ready to focus on designing and doing case study research, others may espouse and advocate other research methods. Similarly, prevailing federal or other research funds may favor other methods, but not the case study. As a result, you may need to have ready responses to some inevitable questions.

First and foremost, you should explain and show how you are devoting yourself to following a rigorous methodological path. The path begins with a thorough literature review and the careful and thoughtful posing of research questions or objectives. Equally important will be a dedication to formal and explicit procedures when doing your research. Along these lines, this book offers much guidance. It shows how case study research includes procedures central to all types of research methods, such as protecting against threats to validity, maintaining a “chain of evidence,” and investigating and testing “rival explanations.” The successful experiences of scholars and students, for over 25 years, may attest to the potential payoffs from using this book.

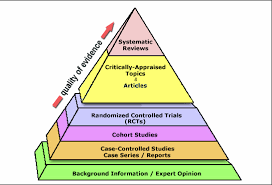

Second, you should understand and openly acknowledge the strengths and limitations of case study research. Such research, like any other, complements the strengths and limitations of other types of research. In the face of those who might only see the need for a single research method, this book believes that, just as different scientific methods prevail in the natural sciences, different social science research methods fill different needs and situations for investigating social science topics. For instance, in the natural sciences, astronomy is a science but does not rely on the experimental method. Similarly, much neurophysiological and neuroanatomical research does not rely on statistical methods. For social science, later portions of this chapter present more about the potential “niches” of different research methods.

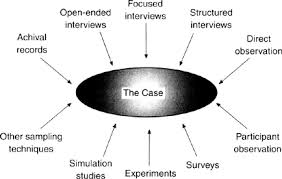

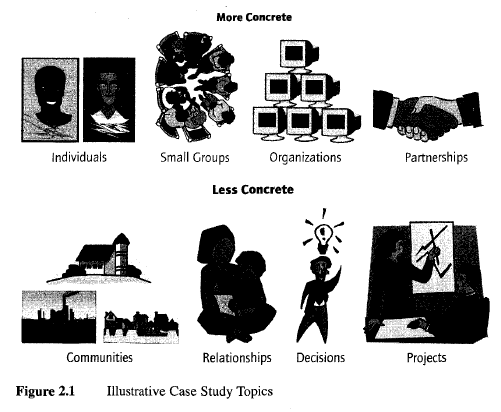

As a research method, the case study is used in many situations, to contribute to our knowledge of individual, group, organizational, social, political, and related phenomena. Not surprisingly, the case study has been a common research method in psychology, sociology, political science, anthropology, social work, business, education, nursing, and community planning. Case studies are even found in economics, in which the structure of a given industry or the economy of a city or a region may be investigated. In all of these situations, the distinctive need for case studies arises out of the desire to understand complex social phenomena. In brief, the case study method allows investigators to retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events—such as individual life cycles, small group behavior, organizational and managerial processes, neighborhood change, school performance, international relations, and the maturation of industries.

This method covers the distinctive characteristics of the case study as a research method. We will help you to deal with some of the more difficult questions still frequently neglected by available research texts. So often, for instance, the author has been confronted by a student or colleague who has asked (a) how to define the “case” being studied, (b) how to determine the relevant data to be collected, or (c) what to do with the data, once collected. This book answers these questions and more, by covering all of the phases of design, data collection, analysis, and reporting.

Main contentsSee more from basic to advanced

At the same time, the book does not cover all uses of case studies. For example, it is not intended to help those who might use case studies as a teaching tool, popularized in the fields of law, business, medicine, or public policy (see Garvin, 2003; Llewellyn, 1948; Stein, 1952; Towl, 1969; Windsor & Greanias, 1983) but now prevalent in virtually every academic field, including the natural sciences. For teaching purposes, a case study need not contain a complete or accurate rendition of actual events. Rather, the purpose of the “teaching case” is to establish a framework for discussion and debate among students. The criteria for developing good cases for teaching—usually of the single- and not multiple-case variety—are different from those for doing research (e.g., Caulley & Dowdy, 1987). Teaching case studies need not be concerned with the rigorous and fair presentation of empirical data; research case studies need to do exactly that.

Similarly, this book is not intended to cover those situations in which cases are used as a form of record keeping. Medical records, social work files, and other case records are used to facilitate some practice, such as medicine, law, or social work. Again, the criteria for developing good cases for practice differ from those for doing case study research.

In contrast, the rationale for this book is that case studies are commonly used as a research method in the social science disciplines—psychology (e.g., D. T. Campbell, 1975; Hersen & Barlow, 1976), sociology (e.g., Hamel, 1992; Platt, 1992; Ragin & Becker, 1992), political science (e.g., George & Bennett, 2004; Gerring, 2004), and anthropology—and for doing research in different professional fields, such as social work (e.g., Gilgun, 1994), business and marketing (e.g., Benbasat, Goldstein, & Mead, 1987; Bonoma, 1985; Ghauri & Grdnhaug, 2002; Gibbert & Ruigrok, 2007; Graebner & Eisenhardt, 2004; Voelpel, Leibold, Tekie, & von Krogh, 2005), public administration (e.g., Agranoff & Radin, 1991; Perry & Kraemer, 1986), public health (e.g., Pluye, Potvin, Denis, Pelletier, & Mannoni, 2005; Richard et al., 2004), education (e.g., Yin, 2006a; Yin & Davis, 2006), accounting (e.g., Brans, 1989), and evaluation (e.g., U.S. Government Accountability Office, 1990).

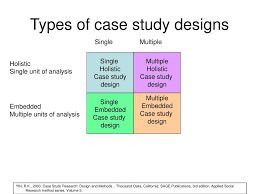

You as a social scientist would like to know how to design and conduct single- or multiple-case studies to investigate a research issue. You may only be doing a case study or may be using it as part of a larger mixed methods study (see Chapter 2). Whichever, this book covers the entire range of issues in designing and doing case studies, including how to start a case study, collect case study evidence, analyze case study data, and compose a case study report.

Source: Yin K Robert (2008), Case Study Research Designs and Methods, SAGE Publications, Inc; 4th edition.

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021