On April 1, 2031, George and Mildred Marvin met with Chip Norton in their research lab (which also doubled as a bicycle shed) to celebrate the incorporation of Marvin Enterprises. The three entrepreneurs had raised $100,000 from savings and personal bank loans and had purchased 1 million shares in the new company. At this zero-stage investment, the company’s

assets were $90,000 in the bank ($10,000 had been spent for legal and other expenses of setting up the company), plus the idea for a new product, the household gargle blaster. George Marvin was the first to see that the gargle blaster, up to that point an expensive curiosity, could be commercially produced using microgenetic refenestrators.

Marvin Enterprises’ bank account steadily drained away as design and testing proceeded. Local banks did not see Marvin’s idea as adequate collateral, so a transfusion of equity capital was clearly needed. Preparation of a business plan was a necessary first step. The plan was a confidential document describing the proposed product, its potential market, the underlying technology, and the resources (time, money, employees, and plant and equipment) needed for success.

Most entrepreneurs are able to spin a plausible yarn about their company. But it is as hard to convince a venture capitalist that your business plan is sound as to get a first novel published.1 Marvin’s managers were able to point to the fact that they were prepared to put their money where their mouths were. Not only had they staked all their savings in the company, but they were mortgaged to the hilt. This signaled their faith in the business.

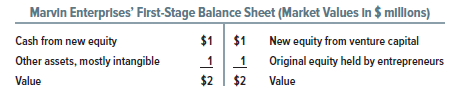

First Meriam Venture Partners was impressed with Marvin’s management team and its business plan and agreed to buy 1 million new shares for $1 each. After this first-stage financing, the company’s market-value balance sheet looked like this:

By agreeing to pay $1 a share for Marvin’s stock, First Meriam placed a value of $1 million on the entrepreneurs’ original shareholdings. This was First Meriam’s estimate of the value of the entrepreneurs’ original idea and their commitment to the enterprise. If the estimate was right, the entrepreneurs could congratulate themselves on a $900,000 paper gain over their original $100,000 investment. In exchange, the entrepreneurs gave up half their company and accepted First Meriam’s representatives to the board of directors.2

The success of a new business depends critically on the effort put in by the managers. Therefore venture capital firms try to structure a deal so that management has a strong incentive to work hard. That takes us back to Chapters 1 and 12, where we showed how the shareholders of a firm (who are the principals) need to provide incentives for the managers (who are their agents) to work to maximize firm value.

If Marvin’s management had demanded watertight employment contracts and fat salaries, they would not have found it easy to raise venture capital. Instead, the Marvin team agreed to put up with modest salaries. They could cash in only from appreciation of their stock. If Marvin failed, they would get nothing because First Meriam actually bought preferred stock designed to convert automatically into common stock when and if Marvin Enterprises succeeded in an initial public offering or consistently generated more than a target level of earnings. But if Marvin Enterprises had failed, First Meriam would have been first in line to claim any salvageable assets. This raised even further the stakes for the company’s management.3 [1]

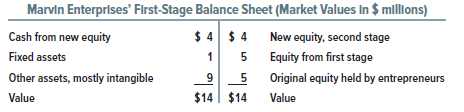

Venture capitalists rarely give a young company up front all the money it will need. At each stage they give enough to reach the next major checkpoint. Thus in spring 2033, having designed and tested a prototype, Marvin Enterprises was back asking for more money for pilot production and test marketing. First Meriam, the original backers, had insisted on pro-rata rights, which gave it the right to participate in subsequent financings. It, therefore, chose to invest $1.5 million in the second-stage financing and a further $2.5 million came from two other venture capital partnerships and wealthy individual investors. The balance sheet just after the second stage was as follows:

Now the after-the-money valuation was $14 million. First Meriam marked up its original investment to $5 million, and the founders noted an additional $4 million paper gain.

Does this begin to sound like a (paper) money machine? It was so only with hindsight. At stage 1, it wasn’t clear whether Marvin would ever get to stage 2; if the prototype hadn’t worked, First Meriam could have refused to put up more funds and effectively closed down the business.[2] Or it could have advanced stage 2 money in a smaller amount on less favorable terms. The board of directors could also have fired George, Mildred, and Chip and gotten someone else to try to develop the business.

In Chapter 14, we pointed out that stockholders and lenders differ in their cash-flow rights and control rights. The stockholders are entitled to whatever cash flows remain after paying off the other security holders. They also have control over how the company uses its money, and it is only if the company defaults that the lenders can step in and take control of the company. When a new business raises venture capital, these cash-flow rights and control rights are usually negotiated separately. The venture capital firm will want a say in how that business is run and will demand representation on the board and a significant number of votes.

The venture capitalist may agree that it will relinquish some of these rights if the business subsequently performs well. However, if performance turns out to be poor, the venture capitalist may automatically get a greater say in how the business is run and whether the existing management should be replaced.

For Marvin, fortunately, everything went like clockwork. Third-stage mezzanine financing was arranged,[3] full-scale production began on schedule, and gargle blasters were acclaimed by music critics worldwide. Marvin Enterprises went public on February 3, 2037. Once its shares were traded, the paper gains earned by First Meriam and the company’s founders turned into fungible wealth. Before we go on to this initial public offering, let us look briefly at the venture capital markets today.

1. The Venture Capital Market

Most new companies rely initially on family funds and bank loans. Some of them continue to grow with the aid of equity investment provided by wealthy individuals known as angel investors. However, like Marvin, many adolescent companies raise capital from specialist venture-capital firms, which pool funds from a variety of investors, seek out fledgling companies to invest in, and then work with these companies as they try to grow. In addition, many large firms act as corporate venturers by providing equity capital to new innovative companies. For example, over the past 20 years, Intel has invested in more than 1,300 firms in 56 countries. In a recent development, young start-ups have also used the Web to raise the money from small investors. This development, known as crowdfunding, is described in the nearby box.

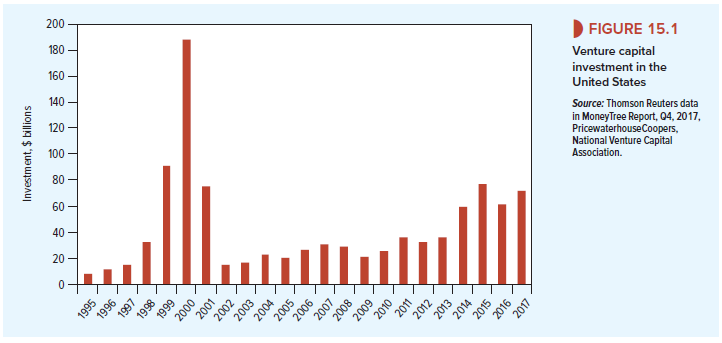

Figure 15.1 shows the changing level of venture capital investment. During the giddy days of 2000, funds invested nearly $200 billion, but since the end of the dot-com boom, venture capital investment has returned to about $60 billion a year.

Most venture capital funds are organized as limited private partnerships with a fixed life of about 10 years. Pension funds and other investors are the limited partners. The management company, which is the general partner, is responsible for making and overseeing the investments and, in return, receives a fixed fee and a share of the profits, called the carried interest.[4] You will find that these venture capital partnerships are often lumped together with similar partnerships that provide funds for companies in distress or that buy out whole companies or divisions of public companies and then take them private. The general term for these activities is private equity investing.

Venture capital firms are not passive investors. They tend to specialize in young high-tech firms that are difficult to evaluate and they monitor these firms closely. They also provide ongoing advice to the firms that they invest in and often play a major role in recruiting the senior management team. Their judgment and contacts can be valuable to a business in its early years and can help the firm to bring its products more quickly to market.[5]

Venture capitalists may cash in on their investment in two ways. Once the new business has established a track record, it is frequently sold out to a larger firm. However, many entrepreneurs do not fit easily into a corporate bureaucracy and would prefer instead to remain the boss. In this case, the company may decide, like Marvin, to go public and so provide the original backers with an opportunity to “cash out,” selling their stock and leaving the original entrepreneurs in control. Approximately 50% of companies going public have been backed by a venture capital company. A thriving venture capital market therefore needs an active stock exchange, such as Nasdaq, that specializes in trading the shares of young, rapidly growing firms.

For every 10 first-stage venture capital investments, only 2 or 3 may survive as successful, self-sufficient businesses. From these statistics come two rules for success in venture capital investment. First, don’t shy away from uncertainty; accept a low probability of success. But don’t buy into a business unless you can see the chance of a big, public company in a profitable market. There’s no sense taking a long shot unless it pays off handsomely if you win. Second, cut your losses; identify losers early, and if you can’t fix the problem—by replacing management, for example—throw no good money after bad.

Venture capital firms have had plenty of failures, but they have also provided early financing for many glamorous growth companies such as Intel, Apple, Microsoft, and Google (now renamed Alphabet). Gornall and Strebulaev examined companies that were supported in their early days with venture capital. They estimated that in 2014, these companies accounted for 20% of the market capitalization of U.S. public companies and 44% of spending on R&D.[7]

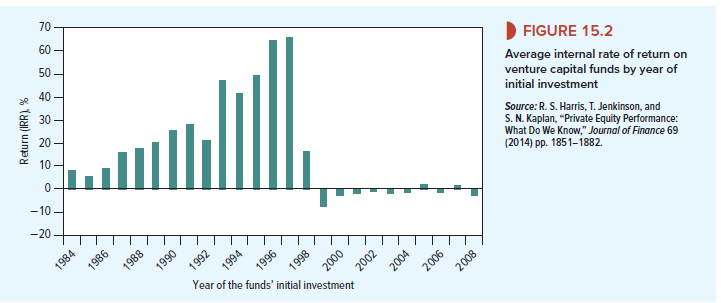

How successful in general is venture capital investment? Figure 15.2 shows the returns to investors in 775 venture capital funds according to the date that the funds made their initial investment.[8] Overall, the average return on the funds was about 17%, more than 15% higher than that of an equivalent investment in the stock market. However, notice how the returns have depended on the year that the fund was established. Those funds formed before 1998 earned dreamy returns, whereas those that came later to the party for the most part made losses.

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thank you Nevertheless I’m experiencing difficulty with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting an identical rss problem? Anyone who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

Pretty great post. I simply stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I’ve really loved surfing around your weblog posts. After all I will be subscribing for your feed and I am hoping you write once more very soon!