There comes a stage in the life of many young companies when they decide to make an initial public offering of stock, or IPO. This may be a primary offering, in which new shares are sold to raise additional cash for the company. Or it may be a secondary offering, where the existing shareholders decide to cash in by selling part of their holdings.

Many IPOs are a mixture of primary and secondary offerings. For example, in 2014, Alibaba’s IPO raised $25 billion. About a third of the shares were sold by the company, but the remainder were sold by existing shareholders. Some of the biggest secondary IPOs arise when a government sells its stake in a company. For example, in 2010, the U.S. Treasury raised $20 billion by selling its holdings of General Motors common and preferred stock. In the same year, the Chinese government raised a similar sum by the sale of the state-owned Agricultural Bank of China.

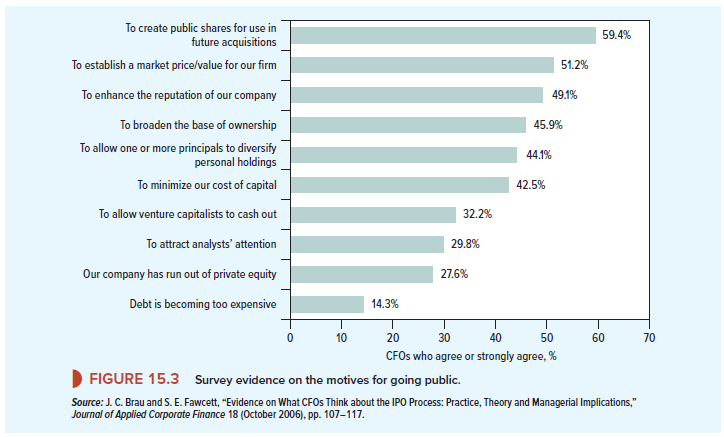

Selling stock for the first time raises cash for the company or for existing shareholders, but as you can see from Figure 15.3, this is by no means the only motive for going public. The most frequently cited reasons are that an IPO allows the firm to use its shares for future acquisitions and establishes a market price for the shares. Raising equity capital for the company comes fairly low in the list of motives.

1. The Public-Private Choice

While there are advantages to being a public corporation, there are also drawbacks. In addition to the fact that they may end up selling shares for less than their true worth,11 there are longer-term costs to operating as a public company. Managers of public companies often chafe at the constant pressure from shareholders to report increases in profits, and they complain at the red tape involved in running a public company. These complaints about red tape have become more vocal since the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), which sought to prevent a repeat of the corporate scandals that brought about the collapse of Enron and WorldCom. As the nearby box suggests, a consequence of SOX has been an increased reporting burden, particularly on small companies and an apparent greater willingness to remain private.[1] Operating as a private company could be tricky if it cut off the company’s access to finance, but in recent years, financial institutions have become more willing to provide equity capital to private firms. For example, in 2017, Airbnb raised $1 billion of private equity in a new funding round.

Some large U.S. companies—such as Cargill, Koch Industries, and Mars Inc.—have been private all their corporate lives. Also, you should not think of the issue process in the United States as a one-way street; public firms often go into reverse and return to being privately owned. For example, Dell became a public company in 1988 and then reverted to being private in 2013, when Michael Dell and a private-equity firm bought out the business. For an extreme example of reversal, consider the food service company, Aramark. It began life in 1936 as a private company and went public in 1960. In 1984, a management buyout led to the company going private, and it remained private until 2001 when it had its second public offering. But the experiment did not last long: Five years later, Aramark was once again the object of a buyout that took the company private again. In 2013, Aramark went public for the third time.

For some years, fewer U.S. companies have been going public, and many new growth companies that are worth a billion dollars or more have increasingly chosen to remain private. As we write this in 2017, these so-called unicorns include such well-known names as Uber, Dropbox, and Airbnb. While the majority of large businesses in the United States are public corporations, the number of public corporations has fallen by about 50% since its high in 1996. It looks as if the case for remaining private may be stronger than it once was.

In response to such concerns Congress passed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act, which eased some of the regulations for small companies that were enacted in SOX. However, not everyone agrees that SOX was responsible for the decline in the number of IPOs. For example, Gao, Ritter, and Zhu point out that the fall in the number of companies going public is concentrated among small venture-backed firms.[2] They argue that it is becoming more difficult for such firms to operate in today’s rapidly changing markets, and therefore, rather than going public, it makes more sense for these firms to sell out to larger firms.

In many countries, private companies are more important than in the United States. For example, Germany’s medium-sized manufacturers, collectively known as the Mittelstand, account for about 50% of national income and 80% of the workforce. These Mittelstand companies are typically privately held, family-owned businesses that rely heavily on bank borrowing to make good any financial deficit.[3] Increasingly, private equity firms have been stepping in to provide the equity capital that they need.

2. Arranging an Initial Public Offering

Let us now look at how Marvin arranged to go public. By 2037, the company had grown to the point at which it needed still more capital to implement its second-generation production technology. At the same time, the company’s founders were looking to sell some of their shares.[4] In the previous few months, there had been a spate of IPOs by high-tech companies, and the shares had generally sold like hotcakes. So Marvin’s management hoped that investors would be equally keen to buy the company’s stock.

Management’s first task was to select the underwriters. Underwriters act as financial midwives to a new issue. Usually they play a triple role: First they provide the company with procedural and financial advice, then they buy the issue, and finally they resell it to the public.

After some discussion, Marvin settled on Klein Merrick as the managing underwriter and Goldman Stanley as the co-manager. Klein Merrick then formed a syndicate of underwriters who would buy the entire issue and reoffer it to the public.

In choosing Klein Merrick to manage its IPO, Marvin was influenced by Merrick’s proposals for making an active market in the stock in the weeks after the issue.[5] Merrick also planned to generate continuing investor interest in the stock by distributing a major research report on Marvin’s prospects.[6] Marvin hoped that this report would encourage investors to hold its stock.

Together with Klein Merrick and firms of lawyers and accountants, Marvin prepared a registration statement for the approval of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).[7] This statement is a detailed and somewhat cumbersome document that presents information about the proposed financing and the firm’s history, existing business, and plans for the future.

The most important sections of the registration statement are distributed to investors in the form of a prospectus. In the appendix to this chapter, we have reproduced the prospectus for Marvin’s first public issue of stock. Real prospectuses would go into much more detail on each topic, but this example should give you some feel for the mixture of valuable information and redundant qualification that characterizes these documents. The Marvin prospectus also illustrates how the SEC insists that investors’ eyes are opened to the dangers of purchase (see “Certain Considerations” in the prospectus). Some investors have joked that if they read each prospectus carefully, they would not dare to buy any new issue.

In addition to registering the issue with the SEC, Marvin needed to check that the issue complied with the so-called blue-sky laws of each state that regulate sales of securities within the state.[8] It also arranged for its newly issued shares to be traded on the Nasdaq exchange.

3. The Sale of Marvin Stock

While Marvin was responding to the SEC’s comments on the registration statement, the company and its underwriters began to firm up the issue price. First they looked at the price- earnings ratios of the shares of Marvin’s principal competitors. Then they worked through a number of discounted-cash-flow calculations like the ones we described in Chapters 4 and 11. Most of the evidence pointed to a market price in the region of $74 to $76 a share, and the company therefore included this provisional figure in an amended version of the prospectus.[9]

Marvin and Klein Merrick arranged a road show to talk to potential investors. Mostly these were institutional investors, such as managers of mutual funds and pension funds. The investors gave their reactions to the issue and indicated to the underwriters how much stock they wished to buy. Some stated the maximum price that they were prepared to pay, but others said that they just wanted to invest so many dollars in Marvin at whatever issue price was chosen. These discussions with fund managers allowed Klein Merrick to build up a book of potential orders.[10] Although the managers were not bound by their responses, they knew that, if they wanted to keep in the underwriters’ good books, they should be careful not to go back on their expressions of interest. The underwriters also were not obliged to treat all investors equally. Some investors who were keen to buy Marvin stock were disappointed in the allotment that they subsequently received.

Immediately after it received clearance from the SEC, Marvin and the underwriters met to fix the issue price. Investors had been enthusiastic about the story that the company had to tell and it was clear that they were prepared to pay more than $76 for the stock. Marvin’s managers were tempted to go for the highest possible price, but the underwriters were more cautious. Not only would they be left with any unsold stock if they overestimated investor demand, but they also argued that some degree of underpricing was needed to tempt investors to buy the stock. Marvin and the underwriters therefore compromised on an issue price of $80. Potential investors were encouraged by the fact that the offer price was higher than the $74 to $76 proposed in the preliminary prospectus and decided that the underwriters must have encountered considerable enthusiasm for the issue.

Although Marvin’s underwriters were committed to buy only 900,000 shares from the company, they chose to sell 1,035,000 shares to investors. This left the underwriters short of 135,000 shares or 15% of the issue. If Marvin’s stock had proved unpopular with investors and traded below the issue price, the underwriters could have bought back these shares in the marketplace. This would have helped to stabilize the price and would have given the underwriters a profit on the sale of these extra shares. As it turned out, investors fell over themselves to buy Marvin stock, and by the end of the first day, the stock was trading at $105. The underwriters would have incurred a heavy loss if they had been obliged to buy back the extra shares at $105. However, Marvin had provided underwriters with a greenshoe option that allowed them to buy an additional 135,000 shares from the company. This ensured that the underwriters were able to sell the extra shares to investors without fear of loss.

After a mandatory “quiet period” of 40 days following the sale, several of Marvin’s underwriters published research reports on the company and recommended buying the stock.

4. The Underwriters

Marvin’s underwriters were prepared to enter into a firm commitment to buy the stock and then offer it to the public. Thus they took the risk that the issue might flop and they would be left with unwanted stock. Occasionally, where the sale of common stock is regarded as particularly risky, the underwriters may be prepared to handle the sale only on a best-efforts basis. In this case the underwriters promise to sell as much of the issue as possible, but they do not guarantee to sell the entire amount.

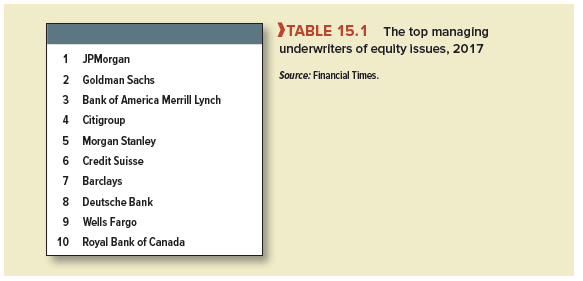

Successful underwriting requires financial muscle and considerable experience. The names of Marvin’s underwriters are, of course, fictitious, but Table 15.1 shows that underwriting is dominated by the major investment banks and large commercial banks. Foreign players are also heavily involved in underwriting securities that are sold internationally.

Underwriting is not always fun. In April 2008, a British bank, HBOS, offered its shareholders two new shares at a price of £2.75 for each five shares that they currently held.[12] The underwriters to the issue, Morgan Stanley and Dresdner Kleinwort, guaranteed that at the end of eight weeks they would buy any new shares that the stockholders did not want. At the time of the offer, HBOS shares were priced at about £5, so the underwriters felt confident that they would not have to honor their pledge. Unfortunately, they reckoned without the turbulent market in bank shares that year. The bank’s shareholders worried that the money they were asked to provide would go to bailing out the bondholders and depositors. By the end of the eight weeks, the price of HBOS stock had slumped below the issue price, and the underwriters were left with 932 million unwanted shares worth £3.6 billion.

Companies get to make only one IPO, but underwriters are in the business all the time. Wise underwriters, therefore, realize that their reputation is on the line and will not handle an issue unless they believe the facts have been presented fairly to investors. So, when a new issue goes wrong, the underwriters may be blamed for overhyping the issue and failing in their “due diligence.” For example, in December 1999, software company Va Linux went public at $30 a share. The next day, trading opened at $299 a share, but then the price began to sag. Within two years, it had fallen below $2. Disgruntled Va Linux investors sued the underwriters, complaining that the prospectus was “materially false.” These underwriters had plenty of company because following the collapse of the dot-com stocks in 2000, investors in many other high- tech IPOs sued the underwriters. As the nearby box explains, there was further embarrassment when it emerged that several well-known underwriters had engaged in “spinning”—that is, allocating stock in popular new issues to managers of their important corporate clients. The underwriter’s seal of approval for a new issue no longer seemed as valuable as it once had.

5. Costs of a New Issue

We have described Marvin’s underwriters as filling a triple role—providing advice, buying the new issue, and reselling it to the public. In return, they received payment in the form of a spread; that is, they were allowed to buy the shares for less than the offering price at which the shares were sold to investors.[13] Klein Merrick as syndicate manager kept 20% of this spread. A further 25% of the spread was used to pay those underwriters who bought the issue. The remaining 55% went to the firms that provided the sales force.

The underwriting spread on the Marvin issue amounted to 7% of the total sum raised from investors. Since many of the costs incurred by underwriters are fixed, you would expect that the percentage spread would decline with issue size. This, in part, is what we find. For example, a $5 million IPO might carry a spread of 10%, while the spread on a $300 million issue might be only 5%. However, Chen and Ritter found that for almost every IPO between $20 and $80 million the spread was exactly 7%.[14] Since it is difficult to believe that there are no scale economies, this clustering at 7% is a puzzle.[15]

In addition to the underwriting fee, Marvin’s new issue entailed substantial administrative costs. Preparation of the registration statement and prospectus involved management, legal counsel, and accountants, as well as the underwriters and their advisers. In addition, the firm had to pay fees for registering the new securities, printing and mailing costs, and so on. You can see from the first page of the Marvin prospectus (see this chapter’s appendix) that these administrative costs totaled $820,000 or just over 1% of the proceeds.

6. Underpricing of IPOs

Marvin’s issue was costly in yet another way. Since the offering price was less than the true value of the issued securities, investors who bought the issue got a bargain at the expense of the firm’s original shareholders.

These costs of underpricing are hidden but nevertheless real. For IPOs, they generally exceed all other issue costs. Whenever any company goes public, it is very difficult to judge how much investors will be prepared to pay for the stock. Sometimes the underwriters misjudge dramatically. For example, when the prospectus for the IPO of eBay was first published, the underwriters indicated that the company would sell 3.5 million shares at a price between $14 and $16 each. However, the enthusiasm for eBay’s web-based auction system was such that the underwriters increased the issue price to $18. The next morning, dealers were flooded with orders to buy eBay; more than 4.5 million shares traded, and the stock closed the day at a price of $47.375.

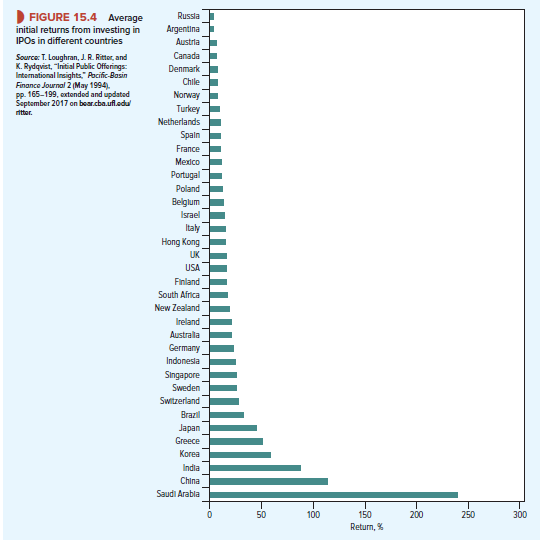

We admit that the eBay issue was unusual.[16] But researchers have found that investors who buy at the issue price on average realize very high returns over the following days. For example, one study of more than 13,000 U.S. IPOs from 1960 to 2017 found average underpricing of 16.8%

Figure 15.4 shows that the United States is not the only country in which IPOs are underpriced. In Saudi Arabia, the gains from buying IPOs have averaged 240%.

You might think that shareholders would prefer not to sell stock in their company for less than its market price, but many investment bankers and institutional investors argue that underpricing is in the interests of the issuing firm. They say that a low offering price on an IPO raises the price when it is subsequently traded in the market and enhances the firm’s ability to raise further capital.

There is another possible reason that it may make sense to underprice new issues. Suppose that you successfully bid for a painting at an art auction. Should you be pleased? It is true that you now own the painting, which was presumably what you wanted, but everybody else at the auction apparently thought that the painting was worth less than you did. In other words, your success suggests that you may have overpaid. This problem is known as the winner’s curse. The highest bidder in an auction is most likely to have overestimated the object’s value and, unless bidders recognize this in their bids, the buyer will, on average, overpay. If bidders are aware of the danger, they are likely to adjust their bids down correspondingly.

The same problem arises when you apply for a new issue of securities. For example, suppose that you decide to apply for every new issue of common stock. You will find that you have no difficulty in getting stock in the issues that no one else wants. But, when the issue is attractive, the underwriters will not have enough stock to go around, and you will receive less stock than you wanted. The result is that your money-making strategy may turn out to be a loser. If you are smart, you will play the game only if there is substantial underpricing on average. Here then we have a possible rationale for the underpricing of new issues. Uninformed investors who cannot distinguish which issues are attractive are exposed to the winner’s curse. Companies and their underwriters are aware of this and need to underprice on average to attract the uninformed investors.

These arguments could well justify some degree of underpricing, but it is not clear that they can account for the occasional underpricing of 100% or more. Skeptics point out that such underpricing is largely in the interests of the underwriters, who want to reduce the risk that they will be left with unwanted stock and also to court popularity by allotting stock to favored clients.

If the skeptics are right, you might expect issuing companies to rebel at being asked to sell stock for much less than it is worth. Think back to our example of eBay. If the company had sold 3.5 million shares at the market price of $47.375 rather than $18, it would have netted an additional $103 million. So why weren’t eBay’s existing shareholders hopping mad? Loughran and Ritter suggest that the explanation lies in behavioral psychology and argue that the cost of underpricing may be outweighed in shareholders’ minds by the happy surprise of finding that they are wealthier than they thought. eBay’s largest shareholder was Pierre Omidyar, the founder and chairman, who retained his entire holding of 15.2 million shares. The initial jump in the stock price from $18 to $47.375 added $447 million to Mr. Omidyar’s wealth. This may well have pushed the cost of underpricing to the back of his mind.[19]

7. Hot New-Issue Periods

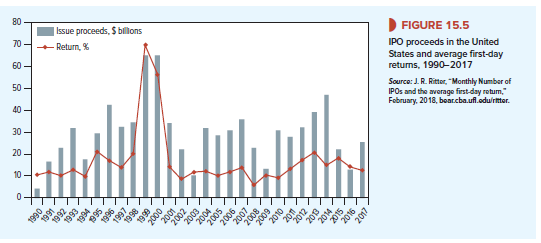

Figure 15.5 shows that the degree of underpricing fluctuates sharply from year to year. In 1999, around the peak of the dot-com boom, new issues raised $65 billion, and the average first-day return on IPOs was 70%. Nearly $37 billion was left on the table that year.[20] But, as the number of new issues slumped, so did the amount of underpricing.

Some observers believe that these hot new-issue periods arise because investors are prone to periods of excessive optimism and would-be issuers time their IPOs to coincide with these periods. Other observers stress the fact that a fall in the cost of capital or an improvement in the economic outlook may mean that a number of new or dormant projects suddenly becomen profitable. At such times, many entrepreneurs rush to raise new cash to invest in these projects.

8. The Long-Run Performance of IPO Stocks

On average investors who buy IPO stocks at the issue price realize high immediate returns, but how do they fare over the longer run? During the period 1980 to 2015 investors who bought the stock of an IPO at the close of the first day’s trading would have lost 18.7% relative to the market over the following three years. This suggests that the initial reaction to the new issues was overenthusiastic. However, much of this poor performance seems to have reflected the fact that IPO stocks were largely those of small growth companies. These companies were generally poor investments during this period. When IPO stocks are compared with those of similar companies, much of the return shortfall disappears.[22]

I truly enjoy looking through on this website , it holds good content.