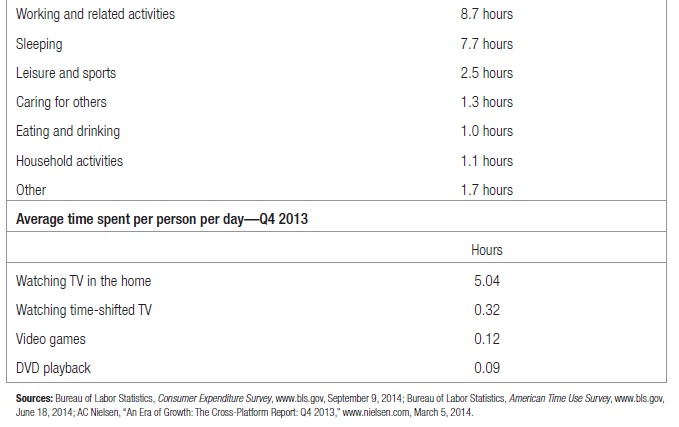

Consumer behavior is the study of how individuals, groups, and organizations select, buy, use, and dispose of goods, services, ideas, or experiences to satisfy their needs and wants.2 Marketers must fully understand both the theory and the reality of consumer behavior. Table 6.1 provides a snapshot profile of U.S. consumers.

A consumer’s buying behavior is influenced by cultural, social, and personal factors. Of these, cultural factors exert the broadest and deepest influence.

1. CULTURAL FACTORS

Culture, subculture, and social class are particularly important influences on consumer buying behavior. Culture is the fundamental determinant of a person’s wants and behavior. Through family and other key institutions, a child growing up in the United States is exposed to values such as achievement and success, activity, efficiency and practicality, progress, material comfort, individualism, freedom, external comfort, humanitarianism, and youthfulness.3 A child growing up in another country might have a different view of self, relationship to others, and rituals.

Marketers must closely attend to cultural values in every country to understand how to best market their existing products and find opportunities for new products. Each culture consists of smaller subcultures that provide more specific identification and socialization for their members. Subcultures include nationalities, religions, racial groups, and geographic regions. When subcultures grow large and affluent enough, companies often design specialized marketing programs to serve them.

Virtually all human societies exhibit social stratification, most often in the form of social classes, relatively homogeneous and enduring divisions in a society, hierarchically ordered and with members who share similar values, interests, and behavior. One classic depiction of social classes in the United States defined seven ascending levels: (1) lower lowers, (2) upper lowers, (3) working class, (4) middle class, (5) upper middles, (6) lower uppers, and (7) upper uppers.4 Social class members show distinct product and brand preferences in many areas.

2. SOCIAL FACTORS

In addition to cultural factors, social factors such as reference groups, family, and social roles and statuses affect our buying behavior.

REFERENCE GROUPS A person’s reference groups are all the groups that have a direct (face-to-face) or indirect influence on their attitudes or behavior. Groups having a direct influence are called membership groups. Some of these are primary groups with whom the person interacts fairly continuously and informally, such as family, friends, neighbors, and coworkers. People also belong to secondary groups, such as religious, professional, and trade-union groups, which tend to be more formal and require less continuous interaction.

Reference groups influence members in at least three ways. They expose an individual to new behaviors and lifestyles, they influence attitudes and self-concept, and they create pressures for conformity that may affect product and brand choices. People are also influenced by groups to which they do not belong. Aspirational groups are those a person hopes to join; dissociative groups are those whose values or behavior an individual rejects.

Where reference group influence is strong, marketers must determine how to reach and influence the group’s opinion leaders. An opinion leader is the person who offers informal advice or information about a specific product or product category, such as which of several brands is best or how a particular product may be used.5 Opinion leaders are often highly confident, socially active, and frequent users of the category. Marketers try to reach them by identifying their demographic and psychographic characteristics, identifying the media they read, and directing messages to them.6

CLIQUES Communication researchers propose a social-structure view of interpersonal communication.7 They see society as consisting of cliques, small groups whose members interact frequently. Clique members are similar, and their closeness facilitates effective communication but also insulates the clique from new ideas. The challenge is to create more openness so cliques exchange information with others in society. This openness is helped along by people who function as liaisons and connect two or more cliques without belonging to either and by bridges, people who belong to one clique and are linked to a person in another.

Best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell claims three factors work to ignite public interest in an idea.8 According to the first, “The Law of the Few,” three types of people help to spread an idea like an epidemic. First are Mavens, people knowledgeable about big and small things. Second are Connectors, people who know and communicate with a great number of other people. Third are Salesmen, who possess natural persuasive power. Any idea that catches the interest of Mavens, Connectors, and Salesmen is likely to be broadcast far and wide. The second factor is “Stickiness.” An idea must be expressed so that it motivates people to act. Otherwise, “The Law of the Few” will not lead to a self-sustaining epidemic. Finally, the third factor, “The Power of Context,” controls whether those spreading an idea are able to organize groups and communities around it.

Not everyone agrees with Gladwell’s ideas.9 One team of viral marketing experts cautions that although in- fluencers or “alphas” start trends, they are often too introspective and socially alienated to spread them. They advise marketers to cultivate “bees,” hyperdevoted customers who are not satisfied just knowing about the next trend but live to spread the word.10 More firms are in fact finding ways to actively engage their passionate brand evangelists. LEGO’s Ambassador Program targets its most enthusiastic followers for brainstorming and feedback.11 Some firms are exploring ways to identify the most influential and potentially lucrative customers online.12

SCORING CONSUMERS ONLINE To better profile and market to customers, firms are exploring different ways to score consumers online. E-scores go beyond personal credit reports to estimate a consumer’s buying power. They take into account factors such as occupation, salary, and home value as well as the amount and nature of luxury and non-luxury purchases. Independent suppliers like EBureau amass the personal information and combine it with a company’s customer database to score a customer from 0 (unprofitable) to 99 (likely to return an investment). Another area of online scoring is influence measurement. A pioneer in the field, Klout measures the clout a person has online with its KloutScores. Klout Scores range from 0 to 100 and are based on analysis of 400 different factors—and 12 billion pieces of data a day—like how influential your followers are and how many people retweet or respond to your messages. President Obama scored a near-perfect 99; singer Justin Bieber scored an impressive 92. Companies like Chevrolet pay Klout to identify and contact influencers for auto purchases. Those people targeted by Chevrolet are given special perks, like a three- day test drive of a Volt, in hopes that they will talk up the car on social media.

Of course, much word-of-mouth is offline person-to-person communication—face to face or over the phone. One of the most valuable sources of information is almost always “people I know and trust.”13 Some word-of- mouth tactics walk a fine line between acceptable and unethical. One controversial tactic, sometimes called shill marketing or stealth marketing, pays people to anonymously promote a product or service in public places without disclosing their financial relationship to the sponsoring firm.

To launch its T681 mobile camera phone, Sony Ericsson hired actors dressed as tourists to approach people at tourist locations and ask to have their photo taken. Handing over the mobile phone created an opportunity to discuss its merits, but many found the deception distasteful.14 Shill marketing is also a problem online, where the legitimacy of a customer or so-called expert reviewer may be hard to verify.

FAMILY The family is the most important consumer buying organization in society, and family members constitute the most influential primary reference group.15 There are two families in the buyer’s life. The family of orientation consists of parents and siblings. From parents a person acquires an orientation toward religion, politics, and economics and a sense of personal ambition, self-worth, and love.16 Even if the buyer no longer interacts very much with his or her parents, parental influence on behavior can be significant. Almost 40 percent of families have auto insurance with the same company as the husband’s parents.

A more direct influence on everyday buying behavior is the family of procreation—namely, the person’s spouse and children. In the United States, in a traditional husband-wife relationship, engagement in purchases has varied widely by product category. The wife has usually acted as the family’s main purchasing agent, especially for food, sundries, and staple clothing items. Now traditional purchasing roles are changing, and marketers would be wise to see both men and women as possible targets.

For expensive products and services such as cars, vacations, or housing, the vast majority of husbands and wives engage in joint decision making.17 Men and women may respond differently to marketing messages, however. Research has shown that women value connections and relationships with family and friends and place a higher priority on people than on companies. Men, on the other hand, relate more to competition and place a high priority on action.18 Marketers have taken direct aim at women with new products such as Quaker’s Nutrition for Women cereals and Crest Rejuvenating Effects toothpaste.

Another shift in buying patterns is an increase in the amount of dollars spent by and the direct and indirect influence wielded by children and teens. Direct influence describes children’s hints, requests, and demands— “I want to go to McDonald’s.” Indirect influence means parents know the brands, product choices, and preferences of their children without hints or outright requests—“I think Jake and Emma would want to go to Panera” Research has shown that more than two-thirds of 13- to 21-year-olds make or influence family purchase decisions on audio/video equipment, software, and vacation destinations.19 In total, these teens and young adults spend more than $120 billion a year. They report that to make sure they buy the right products, they watch what their friends say and do as much as what they see or hear in an ad or are told by a salesperson in a store.

Television can be especially powerful in reaching children, and marketers are using it to target them at younger ages than ever before with product tie-ins for just about everything—Disney Princess character pajamas, retro G.I. Joe toys and action figures, Dora the Explorer backpacks, and Toy Story playsets.

By the time children are about 2 years old, they can often recognize characters, logos, and specific brands. They can distinguish between advertising and programming by about ages 6 or 7. A year or so later, they can understand the concept of persuasive intent on the part of advertisers. By 9 or 10, they can perceive the discrepancies between message and product.20

ROLES AND STATUS We each participate in many groups—family, clubs, organizations—and these are often an important source of information and help to define norms for behavior. We can define a person’s position in each group in terms of role and status. A role consists of the activities a person is expected to perform. Each role in turn connotes a status. A senior vice president of marketing may have more status than a sales manager, and a sales manager may have more status than an office clerk. People choose products that reflect and communicate their role and their actual or desired status in society. Marketers must be aware of the status-symbol potential of products and brands.

3. PERSONAL FACTORS

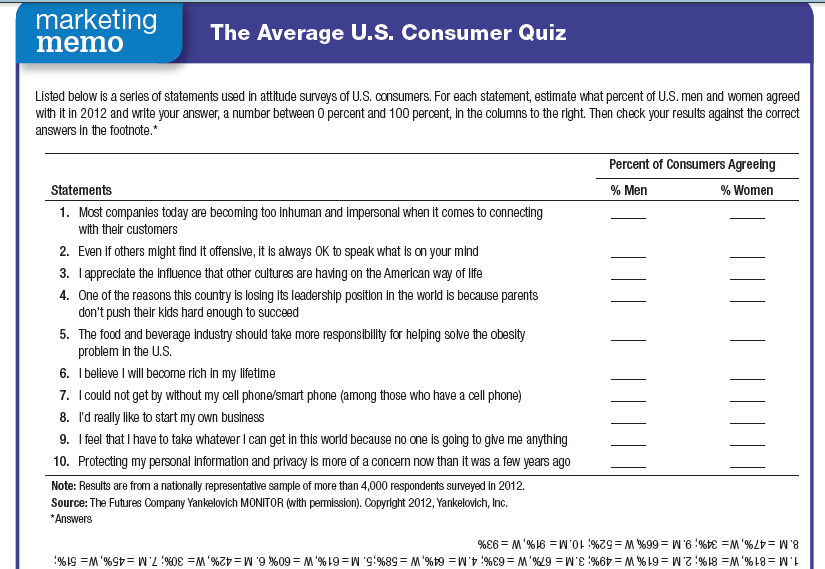

Personal characteristics that influence a buyer’s decision include age and stage in the life cycle, occupation and economic circumstances, personality and self-concept, and lifestyle and values. Because many of these have a direct impact on consumer behavior, it is important for marketers to follow them closely. See how well you do with “Marketing Memo: The Average U.S. Consumer Quiz.”

AGE AND STAGE IN THE LIFE CYCLE Our taste in food, clothes, furniture, and recreation is often related to our age. Consumption is also shaped by the family life cycle and the number, age, and gender of people in the household at any point in time. U.S. households are increasingly fragmented—the traditional family of four with a husband, wife, and two kids makes up a much smaller percentage of total households than it once did. The 2010 census revealed that the average U.S. household size was 2.6 persons.21

In addition, psychological life-cycle stages may matter. Adults experience certain passages or transformations as they go through life.22 Their behavior during these intervals, such as when becoming a parent, is not necessarily fixed but changes with the times.

Marketers should also consider critical life events or transitions—marriage, childbirth, illness, relocation, divorce, first job, career change, retirement, death of a spouse—as giving rise to new needs. These should alert service providers—banks, lawyers, and marriage, employment, and bereavement counselors—to ways they can help.

Not surprisingly, the baby industry attracts many marketers given the enormous amount parents spend—it’s estimated to be a $36 billion market annually—and its life-changing nature.23

THE BABY MARKET Although they may not yet have reached their full earning potential, expectant and new parents seldom hold back when spending on their loved ones, making the baby industry more recession-proof than most. Spending tends to peak between the second trimester of pregnancy and the 12th week after birth. First-time mothers-to-be are especially attractive targets given the fact they will be unable to use many hand-me-downs and will need to buy the full range of new furniture, strollers, toys, and baby supplies. Recognizing the importance of reaching expectant parents early to win their trust—industry pundits call it a “first in, first win” opportunity—marketers use a variety of media including direct mail, inserts, space ads, e-mail marketing, and Web sites. Product samples are especially popular; kits are often given at childbirth education classes and other places. Many hospitals have banned the traditional bedside gift bag, though, concerned with privacy and potentially adverse effects on a vulnerable audience (for example, distributing baby formula may discourage new mothers from breast-feeding). Avenues of access still exist. Partnering with a company that sells baby bedside photos, Disney Baby hands out playful Disney Cuddly Bodysuits and solicits sign-ups for e-mail alerts from DisneyBaby.com. Not all expenditures go directly to the baby. Going through such a fundamental life change, expectant or new parents have a whole new set of needs that has them thinking differently about life insurance, financial services, real estate, home improvement, and automobiles.

OCCUPATION AND ECONOMIC CIRCUMSTANCES Occupation also influences consumption patterns. Marketers try to identify the occupational groups that have above-average interest in their products and services and even tailor products for certain occupational groups: Computer software companies, for example, design different products for brand managers, engineers, lawyers, and physicians.

As the recent prolonged recession clearly indicated, both product and brand choice are greatly affected by economic circumstances like spendable income (level, stability, and pattern over time), savings and assets (including the percentage that is liquid), debts, borrowing power, and attitudes toward spending and saving. Although luxury-goods makers such as Gucci, Prada, and Burberry may be vulnerable to an economic downturn, some luxury brands did surprisingly well in the latest recession.24 If economic indicators point to a recession, marketers can take steps to redesign, reposition, and reprice their products or introduce or increase the emphasis on discount brands so they can continue to offer value to target customers.

PERSONALITY AND SELF-CONCEPT By personality, we mean a set of distinguishing human psychological traits that lead to relatively consistent and enduring responses to environmental stimuli including buying behavior. We often describe personality in terms of such traits as self-confidence, dominance, autonomy, deference, sociability, defensiveness, and adaptability.25

Brands also have personalities, and consumers are likely to choose brands whose personalities match their own. We define brand personality as the specific mix of human traits that we can attribute to a particular brand. Stanford’s Jennifer Aaker researched brand personalities and identified the following traits:26

- Sincerity (down to earth, honest, wholesome, and cheerful) The baby market, targeting expectant and new parents, is

- Excitement (daring, spirited, imaginative, and up to date) highly lucrative for marketers.

- Competence (reliable, intelligent, and successful)

- Sophistication (upper-class and charming)

- Ruggedness (outdoorsy and tough)

Aaker analyzed some well-known brands and found that a number tended to be strong on one particular trait: Levi’s on “ruggedness”; MTV on “excitement”; CNN on “competence”; and Campbell’s on “sincerity.” These brands will, in theory, attract users high on the same traits. A brand personality may have several attributes: Levi’s suggests a personality that is also youthful, rebellious, authentic, and American.

A cross-cultural study exploring the generalizability of Aaker’s scale outside the United States found three of the five factors applied in Japan and Spain, but a “peacefulness” dimension replaced “ruggedness” in both countries, and a “passion” dimension emerged in Spain instead of “competence.”27 Research on brand personality in Korea revealed two culture-specific factors—“passive likeableness” and “ascendancy”—reflecting the importance of Confucian values in Korea’s social and economic systems.28

Consumers often choose and use brands with a brand personality consistent with their actual self-concept (how we view ourselves), though the match may instead be based on the consumer’s ideal self-concept (how we would like to view ourselves) or even on others’ self-concept (how we think others see us).29 These effects may also be more pronounced for publicly consumed products than for privately consumed goods.30 On the other hand, consumers who are high “self-monitors”—that is, sensitive to the way others see them—are more likely to choose brands whose personalities fit the consumption situation.31

Finally, multiple aspects of self (serious professional, caring family member, active fun-lover) may often be evoked differently in different situations or around different types of people. Some marketers carefully orchestrate brand experiences to express brand personalities. Here’s how San Francisco’s Joie de Vivre does this.32

JOIE DE VIVRE Joie de Vivre Hotels operates a chain of boutique hotels and resorts in the San Francisco area as well as Arizona, Illinois, and Hawaii. Each property’s unique decor, quirky amenities, and thematic style are loosely based on popular magazines. For example, The Hotel del Sol—a converted motel bearing a yellow exterior and surrounded by palm trees wrapped in festive lights—is described as “kind of Martha Stewart Living meets Islands magazine.” The Phoenix, represented by Rolling Stone, is, like the magazine, described as “adventurous, hip, irreverent, funky, and young at heart.” Each one of Joie de Vivre’s more than 30 hotels is an original concept designed to reflect its location and engage the five senses. The boutique concept enables the hotels to offer personal touches, such as vitamins in place of chocolates on pillows.

LIFESTYLE AND VALUES People from the same subculture, social class, and occupation may adopt quite different lifestyles. A lifestyle is a person’s pattern of living in the world as expressed in activities, interests, and opinions. It portrays the “whole person” interacting with his or her environment. Marketers search for relationships between their products and lifestyle groups. A computer manufacturer might find that most computer buyers are achievement-oriented and then aim the brand more clearly at the achiever lifestyle.

Lifestyles are shaped partly by whether consumers are money constrained or time constrained. Companies aiming to serve the money-constrained will create lower-cost products and services. By appealing to thrifty consumers, Walmart has become the largest company in the world. Its “everyday low prices” have wrung tens of billions of dollars out of the retail supply chain, passing the larger part of savings along to shoppers in the form of rock- bottom bargain prices.

Consumers who experience time famine are prone to multitasking, doing two or more things at the same time. They will also pay others to perform tasks because time is more important to them than money. Companies aiming to serve them will create products and services that offer multiple time-saving benefits. For example, multitasking blemish balm (BB) skin creams offer an all-in-one approach to skin care—incorporating moisturizer, anti-aging ingredients, sunscreen, and maybe even whitening.33

In some categories, notably food processing, companies targeting time-constrained consumers need to be aware that these very same people want to believe they’re not operating within time constraints. Marketers call those who seek both convenience and some involvement in the cooking process the “convenience involvement segment,” as Hamburger Helper discovered.34

HAMBURGER HELPER Launched in 1971 in response to tough economic times, the inexpensive pasta-and-powdered-mix Hamburger Helper was designed to quickly and inexpensively stretch a pound of meat into a family meal. With an estimated 44 percent of evening meals prepared in under 30 minutes and given strong competition from fast-food drive-through windows, restaurant deliveries, and precooked grocery store dishes, it might seem that Hamburger Helper’s days of prosperity are numbered. Market researchers found, however, that some consumers don’t want the fastest microwaveable solution possible—they also want to feel good about how they prepare a meal. In fact, on average, they prefer to use at least one pot or pan and 15 minutes of time. To remain attractive to this segment, marketers of Hamburger Helper are always introducing new flavors and varieties such as Tuna Helper, Asian Chicken Helper, and Whole Grain Helper to tap into evolving consumer taste trends. Not surprisingly, the latest economic downturn saw brand sales steadily rise.

Consumer decisions are also influenced by core values, the belief systems that underlie attitudes and behaviors. Core values go much deeper than behavior or attitude and at a basic level guide people’s choices and desires over the long term. Marketers who target consumers on the basis of their values believe that with appeals to people’s inner selves, it is possible to influence their outer selves—their purchase behavior.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

I’ve learn several good stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you set to make one of these great informative website.