In Chapter 1, we defined promotion as all communications initiated by a seller that are addressed to final buyers, channel members, or the general public with the intent to create immediate sales or a positive image for the seller’s product or company. Promotion includes personal selling, advertising, sales promotion, and publicity.

Promotion in international marketing is one form of cross-cultural communication, because it involves a message-sender belonging to one national culture and a message-receiver belonging to a second national culture. Actually, all international business activities depend on cross-cultural communication in one way or another. This subject is so important that Chapter 9 is entirely devoted to planning entry strategies across cultural differences. Suffice it to say at this point that effective cross-cultural communication for promotional or other purposes is more difficult to achieve than effective communication within the same culture.

1. “Made-In” Product Images

When entering a foreign market for the first time, managers should understand that consumers/users in that market are likely to know little or nothing about the product and company, however well known they may be in the home market. But this does not mean that managers can write their promotional messages on a clean slate, particularly when they are entering the market through exports. They will find that foreign consumers/users have already formed judgments about the managers’ country and the products it manufactures. In short, they will confront “made-in” images that may be beneficial or detrimental to their own promotion effort. These images may be factual, fanciful, or, most likely, a mixture of facts and conventional stereotypes. But whatever they may be, they will condition responses to the promotional messages of an international company.

Several studies have established the significance of “made-in” images for international marketing. A pioneer study published in 1963 showed that West Europeans have favorable national self-images but less complimentary images of other countries.5 For example, the French described themselves as pleasure-loving, hard-working, and conscientious, but they were described by the Italians as pleasure-loving, frivolous, and amorous. This inclination to ascribe favorable characteristics to themselves and less favorable characteristics to others also extended to products. Nonetheless, the Europeans often held similar images of the products manufactured by a particular country. For example, respondents in all seven survey countries viewed U.S. products as up to date but of lower quality and less reliable than German products.

A more recent study asked consumers in the United States and Japan to rate the product offerings of the United States, Japan, England, France, and Germany on a seven-point scale in terms of 20 criteria.6 It was found that American consumers believed their country was a leader in heavy industry, mass production, inventiveness, advertising, recognizable brands, and youth appeal. Although Japanese consumers agreed that the United States was a mass producer and a mass distributor and had youth appeal, they did not share the American consumer’s highly favorable image of U.S. products. Instead, they considered U.S. products as more concerned with outward appearance than performance and generally less reliable.

Not surprisingly, Japanese consumers, in turn, had a positive image of their own country’s products, perceiving them as inexpensive, of good workmanship, well advertised, and offering a variety of recognizable brands. They conceded that Japanese products were not luxurious, and there was little pride in owning them. American consumers agreed that Japanese products were inexpensive, not luxurious, and offered little in ownership pride, but they also saw them as more concerned with outward appearance than with performance and not highly reliable. In brief, each group more or less mistrusted the other country’s products. With respect to the other countries, American consumers held generally favorable images of German and English products but a generally unfavorable image of French products, while Japanese consumers held generally favorable images of German and French products but a generally unfavorable image of English products.

“Made-in” images can change over time. Perhaps the most striking change has occurred for Japanese products, which before the Second World War were regarded by Western consumers as shoddy imitations of Western products. In sharp contrast, two surveys undertaken eight years apart indicate a deterioration in the image Japanese businessmen hold of U.S. products.7 In 1967, Japanese businessmen considered American products superior in reliability to those of Japan and France although inferior to those of West Germany and England. But in 1975, Japanese businessmen rated the reliability of American products at the bottom along with those of France. Although “made in the U.S.A.” remained highly rated for “technical advancement” and “worldwide distribution,” it lost first place to Germany in the former attribute and first place to Japan in the second. Overall, the U.S. “made-in” image had declined substantially for Japanese businessmen between 1967 and 1975.

Knowledge of “made-in” images can be very helpful to international managers in planning promotion strategy for a foreign target market. Ordinarily, these images are a mixture of both positive and negative attitudes toward products identified with the managers’ country. Thus Japanese businessmen in the 1975 survey just cited still felt there was a prestige value in owning American products. By appealing to positive attitudes, managers stand a better chance than otherwise to create an attractive brand or com- pdMjMmage with their own promotion. An awareness of “made-in” images can also be a powerful corrective to managers’ ethnocentric biases. As we have observed, people in industrial countries usually have a more favorable image of their own country’s products than foreigners do.8

2. Deciding on a Promotion Strategy: A Planning Model

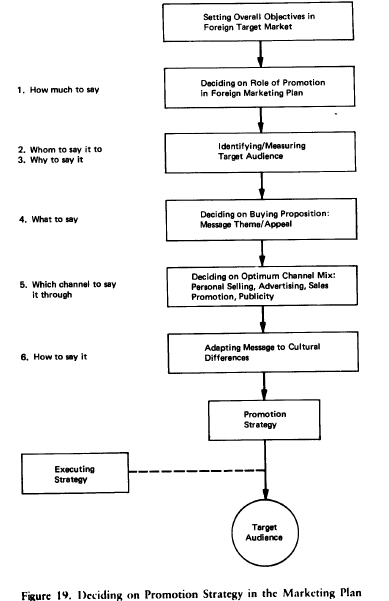

Figure 19 identifies the key decisions that must be made in designing a company’s promotion strategy for a foreign target market.

How Much to Say. The first, and most fundamental, decision concerns the role promotion should have in the international marketing plan. The starting point is the target market objectives established by managers over the entry-planning period, a subject treated earlier. What level of promotion effort is required to attain those objectives? Several considerations bear on the answer to this question. Consumer goods usually need more promotion effort than industrial goods because there are many consumers dispersed over a sizable geographical area. Furthermore, sellers of consumer goods may have to create “psychological” benefits in the minds of consumers through promotion, while sellers of industrial products can appeal to “ra-tional” buying motives by communicating information mostly on product features, performance, and cost. Apart from these general considerations is the company’s own product. As remarked earlier in this chapter, if a product is highly adapted to a particular market segment, it requires less promotion than a product not so adapted.

Other considerations include the size of the target market, the phase of the product’s life cycle, competition, and the entry mode. Evidently, a market with a high company sales potential justifies more promotion effort than one with a smaller potential. Heavier promotion is called for by new- product introduction than by later phases of the life cycle. Again, if competitors promote heavily in the target market, the international company is compelled to match them in some degree. Promotion effort also depends on the entry mode. For instance, a company using foreign distributors may leave promotion entirely or partly to them, but with its own sales subsidiary it must assume the full promotion effort.

To overcome ignorance of their company and product, managers should plan more intensive promotion in markets abroad than at home. But a survey of U.S. industrial companies found that only one-tenth of the surveyed companies were spending more than 1 percent of their international sales on print advertising, while three-tenths were spending more than 1 percent of their domestic sales on print advertising.9 This finding suggests that many U.S. manufacturers would substantially increase their international promotion if they were simply to match their domestic promotion.

Whom to Say It to and Why to Say It. Managers need to specify the target audience or audiences. Should we address our channel members? Or should we address the final consumers or users of our product? Or should we address both? Should we address the general public? The identity of the target audience largely determines the general purpose of promotional messages: managers want channel members to sell more, they want final consumers/users to buy more, and they want the general public to regard their company and product more favorably.

Specific promotion objectives derive from the objectives of the foreign marketing plan. Common objectives include introducing a new product or new product features, developing a favorable brand image, supporting channel members or obtaining new channel members, gaining immediate sales, matching the promotion of competitors, and building goodwill toward the company and its product. Whatever the objectives may be, managers should know why they want to communicate with a target audience. Clearly, the more managers know about that audience—buying motivations and behavior, purchasing power, demographic characteristics, cultural values, and other features—the better they can design their promotion strategy: deciding on the buying proposition, determining the optimum channel mix, and adapting the promotional message to cultural differences. Acquiring information on target audiences is the job of market research, as discussed in Chapter 2.

What to Say. The next step in the model is to decide on the buying proposition, namely, the dominant theme or appeal that managers want to communicate to the target audience. The buying proposition is the idea content of the promotional message—persuasive selling points of the product or company. How the buying proposition is to be presented is contingent on the choice of promotion channels. The creation of an effective buying proposal requires that managers view their product and company from the perspective of the intended receivers in the target market, who belong to a different culture and society. Although a buying proposition used in domestic promotion may be fully transferable to a foreign market, it would be rash for managers to assume that this is always the case.

Which Channel to Say It Through. Basically, communication channels are personal or impersonal. Personal selling, as the name implies, relies on the personal, face-to-face channel; advertising and publicity rely on impersonal channels that reach a mass audience; and sales promotion relies on both personal and impersonal channels, depending on its specific nature.

When international companies use foreign agents or distributors, personal selling in the target market is largely left to those representatives.10 They assume the responsibility for the recruitment, training, and supervision of a sales force. Although an international company may provide technical and sales training and sales aids to its agent/distributor, ordinarily it has little control over the personal selling effort in the target market. Its most active participation occurs when its own missionary salesmen assist foreign representatives.

International companies take on the personal selling function when they establish sales branches/subsidiaries in a target market or when corporate persons undertake missions to foreign markets for face-to-face contacts with prospective final buyers. This latter channel is used principally by companies that negotiate high-unit value transactions (whether of tangible products or of services) with foreign industrial users or governments.

Advertising, the dominant channel for mass promotion, may be defined as any paid form of nonpersonal communication by an identified sponsor to promote a product or company. Advertising employs several specific channels or media, including direct mail, newspapers, magazines, trade journals, radio, television, cinema, and outdoor posters. In deciding on advertising media, managers are concerned with effectiveness (as indicated by coverage, audience selectivity, frequency, and other features) and cost. In general, cost-effectiveness inclines consumer-products companies toward radio, television, and widely distributed print media, while it inclines industrial-products companies toward direct mail, trade journals, and other specialized print media that are aimed at a relatively small number of business prospects. Commonly, the function of industrial advertising is to back up personal selling efforts.

It is seldom possible for a company to duplicate in foreign markets the advertising media mix used in the home market. Countries differ widely in the availability, quality, coverage, audience, and cost of advertising media. Also, national laws regulate advertising in many ways: choice of media, comparative claims, required information, trademarks and labels, and promotion methods, such as contests and premiums. For example, media availability is quite different in Western Europe from what it is in the United States, even though the economies are similar. Television advertising is not allowed in Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, and regulations restrict the time allowed for television advertising in other European countries. Media availability is most limited in the developing countries, where the choice of a media mix is also complicated by the common lack of reliable information on media coverages and audiences.

When used in a specific sense, sales promotion covers all promotion intended to supplement or strengthen personal selling, advertising, and publicity. It includes exhibitions and shows, demonstrations, seminars, contests, sales aids (letters, catalogs, technical bulletins, films, sales kits, and so on), point-of-purchase displays, samples, gifts, premiums, special allowances, and, in general, any promotion effort that is not designated personal selling, advertising, or publicity. Much sales promotion is used to improve the performance of a company’s own salesmen or of its foreign distributors and agents.

One kind of sales promotion is far more important in international than in domestic marketing: trade fairs. International trade fairs are a special kind of market that brings buyers and sellers from different countries together at one place and time. The general trade fair is a big event (usually annual) exhibiting the products of several different industries. The other and more common type of fair is the specialized fair, which displays the products of a single industry or closely affiliated ones, such as Photokina in Cologne. All in all, nearly 100 cities throughout the world host international trade fairs, covering virtually every industry.

Companies entering foreign markets for the first time may find trade fairs a valuable experience. Exhibitors can quickly generate awareness of their product brands and company names, and because visitors come to buy on the spot, they can also test the acceptability of their products before launching a full-scale marketing effort. Exhibitors can also learn much about competitors’ products at first hand. Channel arrangements may also be negotiated with agents and distributors who visit fairs. Finally, exhibitors can use the promotional advantages of personal selling, and, unlike in the usual personal selling situations, they can talk with many potential buyers within a short time and at one place. Furthermore, they can make more striking presentations of their products than possible in ordinary personal selling. In sum, international trade fairs offer the advantages of both personal selling and advertising. As noted in Chapter 3, the U.S. Department of Commerce actively encourages the participation of U.S. companies in international trade fairs by sponsoring exhibits.

Like advertising, publicity is a channel for mass promotion. But unlike advertising, it is commercially significant news about a company or product, disseminated to the general public and not paid for by a sponsor. Because publicity messages are perceived as news, they may have more credibility than advertising messages. We are speaking here of publicity initiated by the international company, not inadvertent publicity which the company does not control and which may be beneficial or detrimental to its interests in the target country/market. Publicity promotion is seldom used with export and licensing entry modes; it is used mostly with investment entry and contractual arrangements with host governments. For instance, the start of new-plant construction in a target country may be turned into a ceremonial occasion with the attendance of leading government officials and full media coverage.

Each promotion channel has its own comparative advantages and disadvantages. Personal selling is generally the most effective channel, as measured by the ratio of sales made to the number of sales contacts. But the cost per sales contact can be very high, because international sales representatives must often travel great distances and remain away from the home country for extended periods. In contrast, advertising offers comparatively low cost per contact, but it also usually generates lower average sales per contact than personal selling. It is impossible to generalize about the advantages and disadvantages of the many forms of sales promotion, some of which closely resemble personal selling and others, advertising. Earlier, we noted the several advantages of trade fairs. Because the many promotion channels are complementary as well as substitutive, a mix of channels is almost certain to provide a more cost-effective promotion program than a single channel.

How to Say It. Effective presentation of the buying proposition in promotional messages can be achieved only through a full understanding of the foreign target audience. Assuming that the buying proposition addresses the needs and motivations of that audience, the question of presentation at the strategic level becomes mainly one of adaptation to the national culture. We therefore defer further discussion on presentation until Chapter 9, which treats cross-cultural communication.

Promotion Strategy. Deciding international promotion strategy is a planning process that is recursive with multiple feedback loops. Although all the questions raised in Figure 19 may not be fully answerable, nonetheless they must be answered if managers are to design a cost-effective promotion strategy. This becomes evident when we consider the several possible sources of failure in promotion: (1) The message does not get through to target receivers because the channel does not reach them. (2) The message is received but is misunderstood, either because of ambiguous content (buying proposition) or, more commonly, because of a presentation that is not responsive to cultural differences. (3) Although understood, the message fails to persuade receivers to change their behavior in the way intended by the sender because of a weak appeal, a weak presentation, or external factors, such as lack of purchasing power. Only a comprehensive approach to international promotion strategy can deal with these several obstacles to effective promotion across economic, political, and cultural differences.

3. A Note to the Reader

We have now completed our elaboration of the first four boxes in the entry-strategy model depicted in Figure 1 in Chapter 1. The focus of this model is on planning entry strategies for a single candidate product in a single target country/market. As stated in Chapter 1, this is the constituent international market entry strategy. But it is not the whcjle story. As a company evolves in international business, its managers must make entry decisions in the context of an ongoing multiproduct/multicountry enterprise system. Entry decisions can no longer be made for a single product and target country in isolation from other products and countries. Some key issues that arise in planning and controlling entry strategies in a multiproduct/multicountry context (including monitoring and revising entry strategies—box 5 in Figure 1) are taken up in Chapter 8. Also, in elaborat- ing the entry model, we have not systematically examined the role of cultural differences in planning and controlling entry strategies. That is done in Chapter 9.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

21 Jul 2021

3 Jun 2021

21 Jul 2021

3 Jun 2021

21 Jul 2021

3 Jun 2021