Although technical analysis is thought to be an ancient method of analyzing markets and prices, its history has been poorly recorded. We do not have recorded evidence of technical analysis being used in ancient times, but it is conceivable that technical analysis, in some form, was used in the distant past in freely traded markets.

Markets in one form or another have existed for centuries. For instance, we know that notes and checks between traders and bankers existed in Babylon by 2000 BC (Braudel, 1981). Currencies, commodities, and participations in mercantile voyages were traded in Ostia, the seaport of Rome, in the second century AD (Braudel, 1982). In the Middle Ages, wheat, bean, oat, and barley prices were available from 1160 on in Angevin, England (Farmer, 1956); and a large grain market existed in Toulouse as early as 1203 (Braudel, 1982). Publicly available evidence suggests that as early as the twelfth century, markets existed in most towns and cities and were linked in a network of arbitrage (Braudel, 1982).

Later, exchanges were developed in which more complicated negotiable instruments, such as state loan stocks, were invented, accepted, and traded. The earliest exchanges appeared in the fourteenth century, mostly in the Mediterranean cities of Pisa, Venice, Florence, Genoa, Valencia, and Barcelona. In fact, the Lonja, the first building constructed as an exchange, was built in 1393 in Barcelona (Carriere, 1973). Witnesses reported that within the Lonja “…a whole squadron of brokers [could be seen] moving in and out of its pillars, and the people standing in little groups were corridors d’orella, the “brokers by ear ” whose job was to listen, report, and put interested parties in touch ” (Carriere, 1973).

The statutes of Verona confirm the existence of the settlement or forward market (mercato a termine), and a jurist named Bartolomo de Bosco is recorded as protesting against a sale of forward loca in Genoa in 1428 (Braudel, 1981). As early as the fifteenth century, Kuxen shares in German mines were quoted at the Liepzig fairs (Maschke) and stocks traded in Hanseatic towns (Sprandel, 1971). A trading market for municipal stocks known as renes sur L ’Hotel existed in France as early as 1522 (Schnapper, 1957).

Can we assume that traders would record prices in these sophisticated markets and would attempt to derive ways to profit from those recordings? It seems likely. Even if prices were not, traders mentally remembering past prices and using these memories to predict future price movements would be using a form of technical analysis.

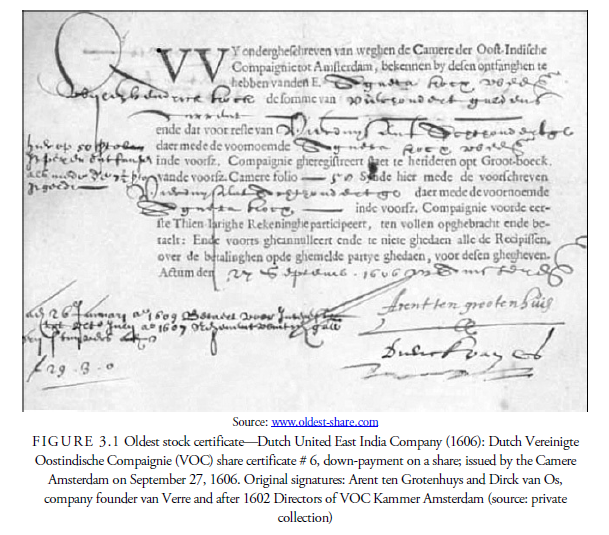

By 1585, public quotes of more than 339 items were reported as traded on the streets and in the coffee houses in Amsterdam (Boxer. 1965). Commodities had been traded there as early as 1530 (Stringham. 2003). The greatest of the early exchanges, the Amsterdam Exchange, called “The Beurs” or “Bourse,” was founded in 1608. The building housing the exchange was built in 1611 and was modeled after the Antwerp Bourse of 1531 (Munro, 2005). This exchange is famous for the “Tulip Bulb Mania” of 1621. By 1722, the Amsterdam Exchange provided trading space for more than 4,500 traders every day between noon and two o’clock (Ricard, 1722). Dealers, brokers, and the public traded and speculated on short sales, forwards, commodities, currencies, shares of ventures, and maritime insurance, as well as other financial instruments, such as notes, bonds, loans, and stocks. They traded grain, herring, spices, whale oil, and, of course, tulips (Kellenbenz, 1957, 1996). The principal stock traded was in the Dutch East India Company. (See Figure 3.1, which is an example of one of the oldest stock shares.) It seems likely that prices for these items were also recorded and analyzed.

In the eighteenth century, as the Dutch empire declined, the London and Paris Exchanges gradually surpassed the Amsterdam Exchange in activity and offerings. In other parts of the world, specifically in Japan, cash-only commodity markets in rice and silver were developing, usually at the docks of major seacoast cities. It is in these markets we first read about a wealthy trader who used technical analysis and trading discipline to amass a fortune.

His name was Sokyo Honma. Born in 1716 as Kosaku Kato in Sakata, Yamagata Prefecture, during the Tokugawa period, he was adopted by the Honma family and took their name. A coastal city, Sakata was a distribution center for rice. Honma became wealthy by trading rice and was known throughout Osaka, Kyoto, and Tokyo. He was promoted to Samurai (not bad for a technical trader) and died in Tokyo at the age of 87.

Honma’s rules are recorded as the “Sakata constitution.” These rules include methods of analyzing one day’s price record to predict the next day’s price, three days of rice prices to predict the fourth day’s price, and rate of change analysis (Shimizu, 1986). None of this information was recorded on charts; they came later in Japan. Honma’s rules might also be considered “trading rules” rather than “technical rules” because they had much to do with how to limit loss and when to step away from markets. Nevertheless, Honma’s methods were based on prices and, thus, largely technical, were successful. Most important, Honma’s methods were recorded.

Because Japan is the first place in which recorded technical rules have been found, many historians have suggested that technical analysis began in the rice markets in Japan. However, it seems inconceivable that technical analysis was not used in the more sophisticated and earlier markets and exchanges in Medieval Europe. Indeed, even in Japan, it is thought that charts were introduced first in the silver market around 1870 by an “English man” (Shimizu, 1986). Thus, technical analysis has a poorly recorded history but by inference is an old method of analyzing trading markets and prices.

Source: Kirkpatrick II Charles D., Dahlquist Julie R. (2015), Technical Analysis: The Complete Resource for Financial Market Technicians, FT Press; 3rd edition.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

Wohh just what I was searching for, thankyou for putting up.