Barriers to entry, which are an important source of monopoly power and profits, sometimes arise naturally. For example, economies of scale, patents and licenses, or access to critical inputs can create entry barriers. However, firms themselves can sometimes deter entry by potential competitors.

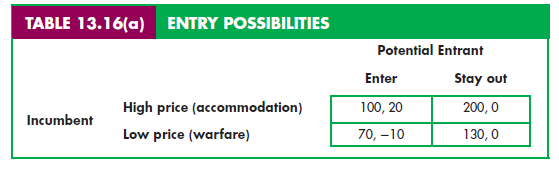

To deter entry, the incumbent firm must convince any potential competitor that entry will be unprofitable. To see how this might be done, put yourself in the posi- tion of an incumbent monopolist facing a prospective entrant, Firm X. Suppose that to enter the industry, Firm X will have to pay a (sunk) cost of $80 million to build a plant. You, of course, would like to induce Firm X to stay out of the industry. If X stays out, you can continue to charge a high price and enjoy monopoly profits. As shown in the upper right-hand corner of the payoff matrix in Table 13.16(a), you would earn $200 million in profits.

If Firm X does enter the market, you must make a decision. You can be “accommodating,” maintaining a high price in the hope that X will do the same. In that case, you will earn only $100 million in profit because you will have to share the market. New entrant X will earn a net profit of $20 million:

$100 million minus the $80 million cost of constructing a plant. (This outcome is shown in the upper left-hand corner of the payoff matrix.) Alternatively, you can increase your production capacity, produce more, and lower your price. The lower price will give you a greater market share and a $20 million increase in revenues. Increasing production capacity, however, will cost $50 million, reduc- ing your net profit to $70 million. Because warfare will also reduce the entrant’s revenue by $30 million, it will have a net loss of $10 million. (This outcome is shown in the lower left-hand corner of the payoff matrix.) Finally, if Firm X stays out but you expand capacity and lower price nonetheless, your net profit will fall by $70 million (from $200 million to $130 million): the $50 million cost of the extra capacity and a $20 million reduction in revenue from the lower price with no gain in market share. Clearly this choice, shown in the lower right-hand corner of the matrix, would make no sense.

If Firm X thinks you will be accommodating and maintain a high price after it has entered, it will find it profitable to enter and will do so. Suppose you threaten to expand output and wage a price war in order to keep X out. If X takes the threat seriously, it will not enter the market because it can expect to lose $10 million. The threat, however, is not credible. As Table 13.16(a) shows (and as the potential competitor knows), once entry has occurred, it will be in your best interest to accommodate and maintain a high price. Firm X’s rational move is to enter the market; the outcome will be the upper left-hand corner of the matrix.

But what if you can make an irrevocable commitment that will alter your incentives once entry occurs—a commitment that will give you little choice but to charge a low price if entry occurs? In particular, suppose you invest the $50 million now, rather than later, in the extra capacity needed to increase output and engage in competitive warfare should entry occur. Of course, if you later maintain a high price (whether or not X enters), this added cost will reduce your payoff.

We now have a new payoff matrix, as shown in Table 13.16(b). As a result of your decision to invest in additional capacity, your threat to engage in com- petitive warfare is completely credible. Because you already have the additional capacity with which to wage war, you will do better in competitive warfare than you would by maintaining a high price. Because the potential competitor now knows that entry will result in warfare, it is rational for it to stay out of the mar- ket. Meanwhile, having deterred entry, you can maintain a high price and earn a profit of $150 million.

Can an incumbent monopolist deter entry without making the costly move of installing additional production capacity? Earlier we saw that a reputation for irrationality can bestow a strategic advantage. Suppose the incumbent firm has such a reputation. Suppose also that by means of vicious price-cutting, this firm has eventually driven out every entrant in the past, even though it incurred losses in doing so. Its threat might then be credible: The incumbent’s irrational- ity suggests to the potential competitor that it might be better off staying away.

Of course, if the game described above were to be indefinitely repeated, then the incumbent might have a rational incentive to engage in warfare whenever entry actually occurs. Why? Because short-term losses from warfare might be outweighed by longer-term gains from preventing entry. Understanding this, the potential competitor might find the incumbent’s threat of warfare credible and decide to stay out. Now the incumbent relies on its reputation for being rational—and far-sighted—to provide the credibility needed to deter entry. The success of this strategy depends on the time horizon and the relative gains and losses associated with accommodation and warfare.

We have seen that the attractiveness of entry depends largely on the way incumbents can be expected to react. In general, once entry has occurred, incum- bents cannot be expected to maintain output at their pre-entry levels. Eventually, they may back off and reduce output, raising price to a new joint profit- maximizing level. Because potential entrants know this, incumbent firms must create a credible threat of warfare to deter entry. A reputation for irrationality can help. Indeed, this seems to be the basis for much of the entry-preventing behavior that goes on in actual markets. The potential entrant must consider that rational industry discipline can break down after entry occurs. By fostering an image of irrationality and belligerence, an incumbent firm might convince potential entrants that the risk of warfare is too high.13

1. Strategic Trade Policy and International Competition

We have seen how a preemptive investment can give a firm an advantage by creating a credible threat to potential competitors. In some situations, a preemp- tive investment—subsidized or otherwise encouraged by the government—can give a country an advantage in international markets and so be an important instrument of trade policy.

Does this conflict with what you have learned about the benefits of free trade? In Chapter 9, for example, we saw how trade restrictions such as tariffs or quotas lead to deadweight losses. In Chapter 16 we go further and show how, in a general way, free trade between people (or between countries) is mutually beneficial. Given the virtues of free trade, how can government intervention in an international market ever be warranted? In certain situations, a country can benefit by adopting policies that give its domestic industries a competitive advantage.

To see how this might occur, consider an industry with substantial economies of scale—one in which a few large firms can produce much more efficiently than many small ones. Suppose that by granting subsidies or tax breaks, the govern- ment can encourage domestic firms to expand faster than they would otherwise. This might prevent firms in other countries from entering the world market, so that the domestic industry can enjoy higher prices and greater sales. Such a policy works by creating a credible threat to potential entrants. Large domes- tic firms, taking advantage of scale economies, would be able to satisfy world demand at a low price; if other firms entered, price would be driven below the point at which they could make a profit.

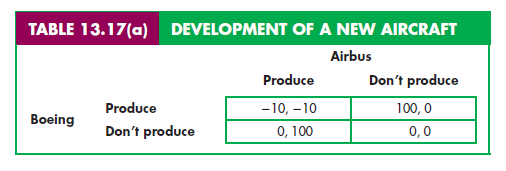

THE COMMERCIAL AIRCRAFT MARKET As an example, consider the inter- national market for commercial aircraft. The development and production of a new line of aircraft are subject to substantial economies of scale; it would not pay to develop a new aircraft unless a firm expected to sell many of them. Suppose that Boeing and Airbus (a European consortium that includes France, Germany, Britain, and Spain) are each considering developing a new aircraft. The ultimate payoff to each firm depends in part on what the other firm does. Suppose it is only economical for one firm to produce the new aircraft. Then the payoffs might look like those in Table 13.17(a).14

If Boeing has a head start in the development process, the outcome of the game is the upper right-hand corner of the payoff matrix. Boeing will produce a new aircraft, and Airbus, realizing that it will lose money if it does the same, will not. Boeing will then earn a profit of 100.

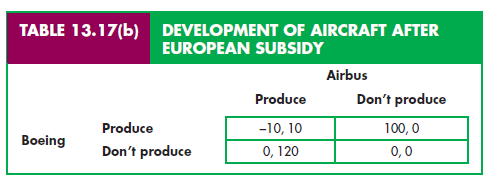

European governments, of course, would prefer that Airbus produce the new aircraft. Can they change the outcome of this game? Suppose they commit to subsidizing Airbus and make this commitment before Boeing has committed itself to produce. If the European governments commit to a subsidy of 20 to Airbus if it produces the plane regardless of what Boeing does, the payoff matrix would change to the one in Table 13.17(b).

Now Airbus will make money from a new aircraft whether or not Boeing produces one. Boeing knows that even if it commits to producing, Airbus will produce as well, and Boeing will lose money. Thus Boeing will decide not to produce, and the outcome will be the one in the lower left-hand corner of Table

13.17(b). A subsidy of 20, then, changes the outcome from one in which Airbus does not produce and earns 0, to one in which it does produce and earns 120. Of this, 100 is a transfer of profit from the United States to Europe. From the European point of view, subsidizing Airbus yields a high return.

European governments did commit to subsidizing Airbus, and during the 1980s, Airbus successfully introduced several new airplanes. The result, how-ever, was not quite the one reflected in our simplified example. Boeing also introduced new airplanes (the 757 and 767 models) that were quite profitable.

As commercial air travel grew, it became clear that both companies could profit-ably develop and sell new airplanes. Nonetheless, Boeing’s market share would have been much larger without the European subsidies to Airbus. One study estimated that those subsidies totalled $25.9 billion during the 1980s and found that Airbus would not have entered the market without them.15

This example shows how strategic trade policy can transfer profits from one country to another. Bear in mind, however, that a country that uses such a pol-icy may provoke retaliation from its trading partners. If a trade war results, all countries can end up much worse off. The possibility of such an outcome mustbe considered befo re a nation adopts a strategic trade policy.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

I like what you guys are up also. Such smart work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my web site :).