The product choice problem and the Stackelberg model are two examples of how a firm that moves first can create a fait accompli that gives it an advantage over its competitor. In this section, we’ll take a broader look at the advantage that a firm can have by moving first. We’ll also consider what determines which firm goes first. We will focus on the following question: What actions can a firm take to gain advantage in the marketplace? For example, how might a firm deter entry by potential competitors, or induce existing competitors to raise prices, reduce output, or leave the market altogether?

Recall that in the Stackelberg model, the firm that moved first gained an advantage by committing itself to a large output. Making a commitment— constraining its future behavior—is crucial. To see why, suppose that the first mover (Firm 1) could later change its mind in response to what Firm 2 does. What would happen? Clearly, Firm 2 would produce a large output. Why? Because it knows that Firm 1 will respond by reducing the output that it first announced. The only way that Firm 1 can gain a first-mover advantage is by committing itself. In effect, Firm 1 constrains Firm 2’s behavior by constraining its own behavior.

The idea of constraining your own behavior to gain an advantage may seem paradoxical, but we’ll soon see that it is not. Let’s consider a few examples.

First, let’s return once more to the product-choice problem shown in Table 13.9. The firm that introduces its new breakfast cereal first will do best. But which firm will introduce its cereal first? Even if both firms require the same amount of time to gear up production, each has an incentive to commit itself first to the sweet cereal. The key word is commit. If Firm 1 simply announces it will produce the sweet cereal, Firm 2 will have little reason to believe it. After all, Firm 2, knowing the incentives, can make the same announcement louder and more vociferously. Firm 1 must constrain its own behavior in some way that convinces Firm 2 that Firm 1 has no choice but to produce the sweet cereal. Firm 1 might launch an expensive advertising campaign describing the new sweet cereal well before its introduction, thereby putting its reputation on the line. Firm 1 might also sign a contract for the forward delivery of a large quantity of sugar (and make the contract public, or at least send a copy to Firm 2). The idea is for Firm 1 to commit itself to produce the sweet cereal. Commitment is a strategic move that will induce Firm 2 to make the decision that Firm 1 wants it to make—namely, to produce the crispy cereal.

Why can’t Firm 1 simply threaten Firm 2, vowing to produce the sweet cereal even if Firm 2 does the same? Because Firm 2 has little reason to believe the threat—and can make the same threat itself. A threat is useful only if it is credible. The following example should help make this clear.

1. Empty Threats

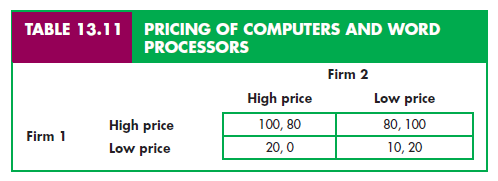

Suppose Firm 1 produces personal computers that can be used both as word processors and to do other tasks. Firm 2 produces only dedicated word processors. As the payoff matrix in Table 13.11 shows, as long as Firm 1 charges a high price for its computers, both firms can make a good deal of money. Even if Firm 2 charges a low price for its word processors, many people will still buy Firm 1’s computers (because they can do so many other things), although some buyers will be induced by the price differential to buy the dedicated word processor instead. However, if Firm 1 charges a low price, Firm 2 will also have to charge a low price (or else make zero profit), and the profit of both firms will be significantly reduced.

Firm 1 would prefer the outcome in the upper left-hand corner of the matrix. For Firm 2, however, charging a low price is clearly a dominant strategy. Thus the outcome in the upper right-hand corner will prevail (no matter which firm sets its price first).

Firm 1 would probably be viewed as the “dominant” firm in this industry because its pricing actions will have the greatest impact on overall industry profits. Can Firm 1 induce Firm 2 to charge a high price by threatening to charge a low price if Firm 2 charges a low price? No, as the payoff matrix in Table 13.11 makes clear: Whatever Firm 2 does, Firm 1 will be much worse off if it charges a low price. As a result, its threat is not credible.

2. Commitment and Credibility

Sometimes firms can make threats credible. To see how, consider the following example. Race Car Motors, Inc., produces cars, and Far Out Engines, Ltd., produces specialty car engines. Far Out Engines sells most of its engines to Race Car Motors, and a few to a limited outside market. Nonetheless, it depends heavily on Race Car Motors and makes its production decisions in response to Race Car’s production plans.

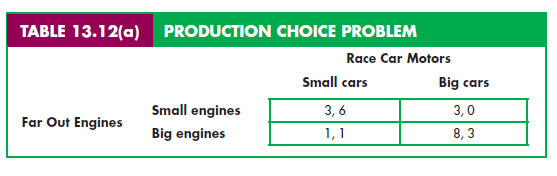

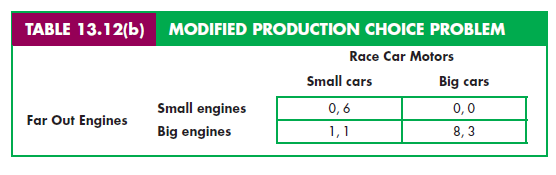

We thus have a sequential game in which Race Car is the “leader.” It will decide what kind of cars to build, and Far Out Engines will then decide what kind of engines to produce. The payoff matrix in Table 13.12(a) shows the possible outcomes of this game. (Profits are in millions of dollars.) Observe that Race Car will do best by deciding to produce small cars. It knows that in response to this decision, Far Out will produce small engines, most of which Race Car will then buy. As a result, Far Out will make $3 million and Race Car $6 million.

Far Out, however, would much prefer the outcome in the lower right-hand corner of the payoff matrix. If it could produce big engines, and if Race Car produced big cars and thus bought the big engines, it would make $8 million. (Race Car, however, would make only $3 million.) Can Far Out induce Race Car to produce big cars instead of small ones?

Suppose Far Out threatens to produce big engines no matter what Race Car does; suppose, too, that no other engine producer can easily satisfy the needs of Race Car. If Race Car believed Far Out’s threat, it would produce big cars: Otherwise, it would have trouble finding engines for its small cars and would earn only $1 million instead of $3 million. But the threat is not credible: Once Race Car responded by announcing its intentions to produce small cars, Far Out would have no incentive to carry out its threat.

Far Out can make its threat credible by visibly and irreversibly reducing some of its own payoffs in the matrix, thereby constraining its own choices. In particular, Far Out must reduce its profits from small engines (the payoffs in the top row of the matrix). It might do this by shutting down or destroying some of its small engine production capacity. This would result in the payoff matrix shown in Table 13.12(b). Now Race Car knows that whatever kind of car it produces, Far Out will produce big engines. If Race Car produces the small cars, Far Out will sell the big engines as best it can to other car producers and settle for making only $1 million. But this is better than making no profits by producing small engines. Because Race Car will have to look elsewhere for engines, its profit will also be lower ($1 million). Now it is clearly in Race Car’s interest to produce large cars. By taking an action that seemingly puts itself at a disadvantage, Far Out has improved its outcome in the game.

Although strategic commitments of this kind can be effective, they are risky and depend heavily on having accurate knowledge of the payoff matrix and the industry. Suppose, for example, that Far Out commits itself to producing big engines but is surprised to find that another firm can produce small engines at a low cost. The commitment may then lead Far Out to bankruptcy rather than continued high profits.

THE ROLE OF REPUTATION Developing the right kind of reputation can also give one a strategic advantage. Again, consider Far Out Engines’ desire to produce big engines for Race Car Motors’ big cars. Suppose that the managers of Far Out Engines develop a reputation for being irrational—perhaps downright crazy. They threaten to produce big engines no matter what Race Car Motors does (refer to Table 13.12a). Now the threat might be credible without any further action; after all, you can’t be sure that an irrational manager will always make a profit-maximizing decision. In gaming situations, the party that is known (or thought) to be a little crazy can have a significant advantage.

Developing a reputation can be an especially important strategy in a repeated game. A firm might find it advantageous to behave irrationally for several plays of the game. This might give it a reputation that will allow it to increase its long- run profits substantially.

3. Bargaining Strategy

Our discussion of commitment and credibility also applies to bargaining problems. The outcome of a bargaining situation can depend on the ability of either side to take an action that alters its relative bargaining position.

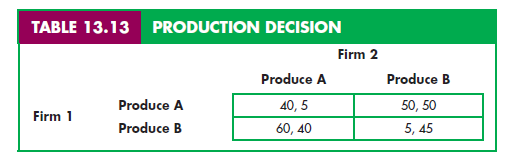

For example, consider two firms that are each planning to introduce one of two products which are complementary goods. As the payoff matrix in Table 13.13 shows, Firm 1 has a cost advantage over Firm 2 in producing A. Therefore, if both firms produce A, Firm 1 can maintain a lower price and earn a higher profit. Similarly, Firm 2 has a cost advantage over Firm 1 in producing product B. If the two firms could agree about who will produce what, the rational outcome would be the one in the upper right-hand corner: Firm 1 produces A, Firm 2 produces B, and both firms make profits of 50. Indeed, even without cooperation, this outcome will result whether Firm 1 or Firm 2 moves first or both firms move simultaneously. Why? Because producing B is a dominant strategy for Firm 2, so (A, B) is the only Nash equilibrium.

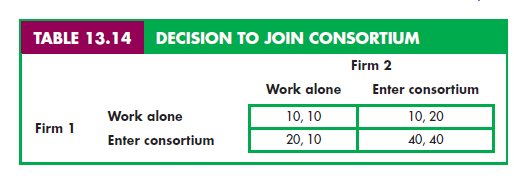

Firm 1, of course, would prefer the outcome in the lower left-hand corner of the payoff matrix. But in the context of this limited set of decisions, it cannot achieve that outcome. Suppose, however, that Firms 1 and 2 are also bargaining over a second issue—whether to join a research consortium that a third firm is trying to form. Table 13.14 shows the payoff matrix for this decision problem. Clearly, the dominant strategy is for both firms to enter the consortium, thereby increasing profits to 40.

Now suppose that Firm 1 links the two bargaining problems by announcing that it will join the consortium only if Firm 2 agrees to produce product A. In this case, it is indeed in Firm 2’s interest to produce A (with Firm 1 producing B) in return for Firm 1’s participation in the consortium. This example illustrates how combining issues in a bargaining agenda can sometimes benefit one side at the other’s expense.

As another example, consider bargaining over the price of a house. Suppose I, as a potential buyer, do not want to pay more than $200,000 for a house that is actually worth $250,000 to me. The seller is willing to part with the house at any price above $180,000 but would like to receive the highest price she can. If I am the only bidder for the house, how can I make the seller think that I will walk away rather than pay more than $200,000?

I might declare that I will never, ever pay more than $200,000 for the house. But is such a promise credible? It may be if the seller knows that I have a reputation for toughness and that I have never reneged on a promise of this sort. But suppose I have no such reputation. Then the seller knows that I have every incentive to make the promise (making it costs nothing) but little incentive to keep it. (This will probably be our only business transaction together.) As a result, this promise by itself is not likely to improve my bargaining position.

The promise can work, however, if it is combined with an action that gives it credibility. Such an action must reduce my flexibility—limit my options—so that I have no choice but to keep the promise. One possibility would be to make an enforceable bet with a third party—for example, “If I pay more than $200,000 for that house, I’ll pay you $60,000.” Alternatively, if I am buying the house on behalf of my company, the company might insist on authorization by the Board of Directors for a price above $200,000, and announce that the board will not meet again for several months. In both cases, my promise becomes credible because I have destroyed my ability to break it. The result is less flexibility—and more bargaining power.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

It is in reality a nice and helpful piece of information. I am happy that you simply shared this useful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.