Remember, the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH) suggests that enough investors are acting rationally at any particular point in time to make it impossible for a technical analyst to profit from security mispricing due to the emotions of the uninformed players. However, the field of behavioral finance has defined numerous ways in which investors act less than rational. These biases are common not just to the occasional investor or uninformed public but to professionals as well. Just look at how many professional securities analysts were caught in the late 1990s stock market euphoria. These were not stupid, irrational people, but their inherent biases, those common to all humans, overcame their ability to reason, and they became caught up in the optimism of the time to tragic effect.

Box 7.3 Investors are Their Own Worst Enemies From Zweig (2007)

-

- Everyone knows that you should buy low and sell high—and yet, all too often, we buy high and sell low.

- Everyone knows that beating the market is nearly impossible—but just about everyone thinks he can do it.

- Everyone knows that panic selling is a bad idea—but a company that announces it earned 23 cents per share instead of 24 cents per share can lose $5 billion of market value in a minute-and-a-half.

- Everyone knows that Wall Street strategists can’t predict what the market is about to do, but investors still hang on every word from the financial pundits who prognosticate on TV.

- Everyone knows that chasing hot stocks or mutual funds is a sure way to get burned, yet millions of investors flock back to the flame every year. Many do so though they swore, just a year or two before, never to get burned again.

…our brains often drive us to do things that make no logical sense—but make perfect emotional sense.

Those who study behavioral finance attribute some of the biased behavior of financial market players to crowd behavior. These researchers have found that crowd opinions are formed by several biases. People tend to conform to their group, making the taking of an opposite opinion sometimes difficult and dangerous. People do not like rejection or ridicule and will stay quiet to avoid such pressure. People often meet hostility when going against a crowd. Another bias is that people gain confidence by extrapolating past trends, even when doing so is irrational, and, thus, they tend to switch their opinions slowly. Also, people feel secure in accepting the opinions of others, especially “experts,” and tend to believe the establishment will take care of them.

Understanding that investor emotion and bias affect investment decisions is important for two reasons. First, understanding the links between emotions, investment behavior, and security prices can help the technical analyst profit by spotting market extremes. Second, technical analysts must remember that they are subject to the same human biases as other investors. This set of human biases is so strong that even those who recognize them still are affected by them and must constantly fight against them. Successful traders and investors often say that the worst enemy in investment is oneself. Technical analysts hope to profit from understanding how human bias can cause people to pay prices greater than the intrinsic value for a stock, but if they are not careful, their own biases may cause them to do the same.

For example, the behavioral finance principle of “representation” suggests that people often recognize patterns where they do not actually exist. Although it is the technical analyst’s strategy to attempt to recognize patterns, an analyst must be certain not to “see” patterns that do not really exist. Therefore, an investor or trader must not only understand our human foibles but find a way to either fight against them or avoid them.

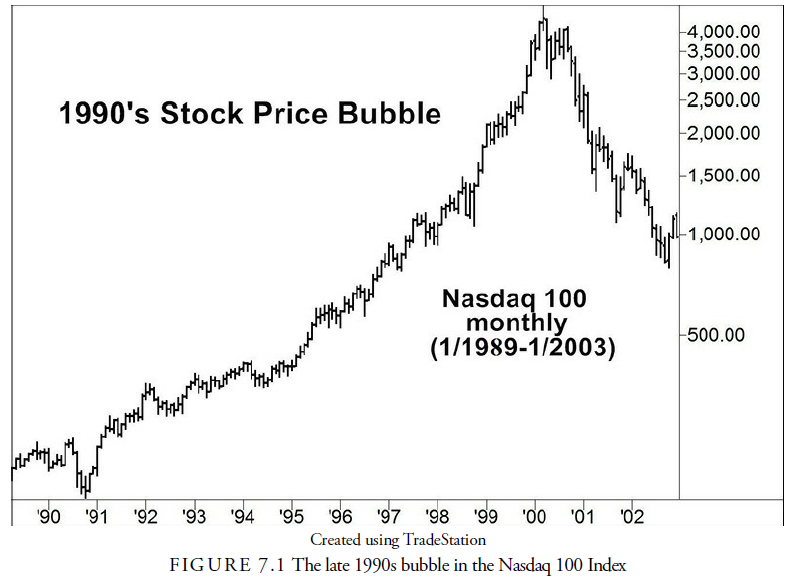

At times, emotional excess leads to extraordinary rises in prices (and sometimes to extraordinary declines, called crashes or panics). These periods of extraordinary price increases, whether in the stock market, gold, or tulip bulbs, are called bubbles. During a bubble, stock market returns are much higher than the mean, or average, return. Bubbles are part of that fat tail mentioned in Chapter 4, “The Technical Analysis Controversy.” Although bubbles occur infrequently, they occur considerably more often than would be expected under an ideal random walk model.

For the current discussion, the existence of bubbles is proof that prices are not always determined rationally; emotion can get hold of the market and, through positive feedback, run prices far beyond any reasonable value before reversing. This type of bubble is visible in Figure 7.1. During the late 1990s, security prices were rapidly increasing. By 2000, security prices were extremely high, especially in the technology sector. The price earnings ratios for many companies were at record highs. For some companies, the price earnings ratios were infinite because there were no earnings at all. In fact, investors would have to assume that earnings would grow at an astounding 100% per year for 20 years to justify the stock prices using traditional stock valuation models. According to investment analyst David Dreman, “This seems to be a classic pattern of investor overreaction” (Dreman, 2002, p. 4). Nevertheless, the bubble occurred, indicating that investors of all kinds can become blind to reality when greed and other psychological biases influence decision making.

Box 7.4 Books on the History of Manias and Panics

A number of excellent books have been written about the manias and panics that characterize the financial markets. For further information about this phenomenon, you can read the following:

Ahamed, Liaquat. Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World. New York, NY: Penguin, 2009.

Allen, Fredrick Lewis. Only Yesterday. New York, NY: First Perennial Classics, 2000.

Amyx, Jennifer. Japan’s Financial Crisis: Institutional Rigidity and Reluctant Change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Bernstein, Peter L. Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1996.

Bruner, Robert F. and Sean D. Carr. The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned from the Market’s Perfect Storm. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009.

Chancellor, Edward. Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation. New York, NY: Plume, 2000.

Galbraith, John K. A Short History of Financial Euphoria. New York, NY: Penguin House, 1994.

Kindlelberger, Charles P. and Robert Z. Aliber. Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, 6th ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011.

Mackay, Charles. Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Amazon: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

Reinhard, Carmen M. and Kenneth Rogoff. This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Schwed, Fred and Peter Arno. Where Are the Customers’ Yachts: or A Good Hard Look at Wall Street. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006.

Shiller, Robert J. Irrational Exuberance. New York, NY: Crown Business, 2006.

Smith, Adam. Money Game. New York, NY: Vintage, 1976.

Sobel, Robert. Panic on Wall Street: A History of America’s Financial Disasters. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1968.

Wicker, Elmus. Banking Panics of the Guilded Age. UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Source: Kirkpatrick II Charles D., Dahlquist Julie R. (2015), Technical Analysis: The Complete Resource for Financial Market Technicians, FT Press; 3rd edition.

8 Jul 2021

7 Jul 2021

6 Jul 2021

7 Jul 2021

7 Jul 2021

6 Jul 2021