Kanizsa (1980) holds that the science of perception stems from questions about how and why the perceptual world is parsed into distinct objects, in particular why just these objects appear and why they are endowed with just that shape, color, size, depth, localization, motion, smell, hardness and so on. To answer these questions with ingenuity, the research has to reject the naive realism of common sense that reduces the phenomenal properties to the material properties of things. Undoubtedly it is the most natural stance for subjects from which to grasp the surrounding world, yet assuming that perception consists in recording external objects makes the questions on perception trivial and psychophysiology or psychophysics the only disciplines to study it. The perceptual structure of the world is explained away with its alleged correspondence to the physical furniture of the world. The study of perception is limited to the sense organs whose sensitivity and margins of error are tested like the accuracy of physical instruments.

Kanizsa claims that this common-sense and scientific view, which reduces perception to the first link of a causal physical and physiological chain, faces some puzzling problems. Firstly, there are cases of experience that put this reduction into question: perceptual illusions, perceptual constancies, phenomenal depth and three-dimensionality despite the two-dimensionality of retinal projection, the distinction of one’s body’s and objects’ movement despite the fact that the same displacement of retinal stimulus may underlie both. Secondly, the analysis of the causal chain shows the mutual independence and isolation of distal and proximal stimuli as well as of cortical mechanisms that do not match the unity and structure of visual objects. It is then difficult to understand how the real unity of external things is retrieved by perception. Kanizsa cites the long-established theory holding that what is lost through the causal chain does not affect the physical-phenomenal correspondence because it is supplemented by unconscious inferences and reasoning or retrieval of memory traces. However, he argues that this theory proves too much. This processing should take so little time that it must remain under a threshold such that the perceptual data cannot bear observable traces of them. Yet if a construct allows hypotheses that cannot in principle be observed, a logical argument could always be used to adjust it to even possible evidence against the hypothesized processing (1985: 30b; infra § 4.1).

Kanizsa (1961) emphasizes that the concept of perception should not be inflated to include memory, imaginative, representational, affective or cognitive effects. Otherwise the alleged evidence that decides between alternative theories of perception is not derived from a real perceptual basis. Kanizsa suggests that a thing, an event, a relation is thoroughly perceptual if it is experienced as “phenomenally real hic et nunc” He concedes that this criterion may not be so clear-cut in some cases. Moreover, he cites Goldmeier who has shown that there is a pure perceptual ability to compare, categorize and understand relations (1976: 91, 1979). At any rate this criterion demands that perception science begins from a description of perceptual objects of direct experience. The design of the experimental conditions has to induce subjects to report the content of experience in such a way that it is as free as possible from the conceptualization or post hoc rationalization of phenomena. Explanatory units are required to match what appears rather than constructs of mental entities and theoretical posits. Kanizsa (1980) claims that the phenomenological method used by Rubin, Katz and Wertheimer takes logical and empirical priority over any theory that one may wish to choose as the most promising candidate to explain perception, even Gestalt theory. The phenomenological method prevents the neglect of the true nature of phenomena, whose investigation may reveal the self-ruling laws of perception; hence, to decide between competing theories.

A case in point is perceptual completion. The fact that a whole object is seen, although parts thereof are occluded, has long been considered a clue for pictorial perception of depth, but Metelli (1940) as well as Michotte and Burke (1951) have shown that this phenomenon belongs to ordinary perception. Since the perceptual world is replete with occluded objects that are yet perceived as complete, Kanizsa argues that the reason for the scarce interest in this phenomenon is that it has long been explained away as the result of a reasoning process that is hypothesized to fill in the missing sensory data. The perceptual problem of completion was thoroughly disregarded or forced to fill a preconceived theoretical scheme, instead of being recognized as a bona fide phenomenon that can be used to study the perceptual structure of the world and the underlying rules of perception. Kanizsa sets out to specify the repeatable content of the completion as a real phenomenon that occurs in the experience of objects.

The part in the middle of 16(a) that is delimited by black marks is as visible as any other part belonging to the whole figure. In the corresponding place nothing is presented in 16(b), which is perceived as two pieces rather than as a rectangle as in 16(a). Of course, one can imagine an additional part that is added to the rectangular pieces in that empty place to form a larger unitary figure. Instead, in the corresponding places of 16(c), one perceives the parts of the whole rectangle although they are not as visible as the rest of the figure, which are yet present as connected parts that are momentarily occluded by the overlying rectangular stripe. In 16(c) perceivers actually see a whole rectangle, whereas 16(b) can only be thought of as two parts of a larger connected figure. Kanizsa (1991: 51, 52) claims that in such a case the parts in 16(b) are interpolated by a non-perceptual function; hence, they are mentally represented. On the contrary, the parts in 16(c) are perceived and not merely represented. The subjects see them lying behind the stripe. The distinction between represented and perceived parts is confirmed by the observation that the interpolation of parts in 16(b) does not change the appearance of the empty place where the white of the background is still seen, while were the parts in 16(c) not present there would be no appearance of the same rectangular surface as in 16(a) continuing behind the occlusion. The compelling character of the distinction, then, is due to the fact that the completion has observable effects on the other visual parts of the figure. The parts that are less visible but are perceptually present are independent of the thought or the imagination of the subjects. They are “encountered,” as Metzger would have said, and appear as “phenomenally real hic and nunc.” Likewise, the conditions that allow them to occur are perceivable: the completion appears only if the visible parts of (at least) two figures are seen in contact with each other and satisfy the grouping factors. The perceptual completion is changed or disappears only if the perceivable components of the scene are altered, while it is not affected by the modification of the subjective attitudes or thoughts (1991: 56). Therefore the perceptual completion is an example of a phenomenon (a kind of contact) that brings about another phenomenon as well as of a rule of perception (a grouping rule) consisting of perceivable factors.

This phenomenon can be extended to the ordinary perceptual experience of the outside world. The stimulation underlying any perceptual scene often makes only some delimited pieces of things directly visible. Moreover, the appearance of the front side of anything always hides its rear side. Yet the subjects never see pieces or fragments of things, rather visual unities all of a whole and complete objects. The findings on the completion show that the subjects do not integrate disconnected pieces into whole things through interpolation by means of psychic functions (1991: 54). Kanizsa concedes that there are interpolations by means of the knowledge stored in memory on how things are, but they are often triggered by the phenomenological conditions of completion. To decide such cases, the effects of the perceptual completion can be employed as phenomenal experimental variables to study the perceptual structure of the world. The perceptual completion becomes a phenomenological probe to answer questions about how and why the world appears articulated in distinct unitary things. It will be sufficient to design a condition in which some transformations applied to a particular part of a visual object or scene either bring about or make disappear the completion that is replaced by forms of mental interpolation. The surfaces with margins without gradients are a demonstration of this kind (1955, 1974; Kanizsa and Gerbino, 1980).

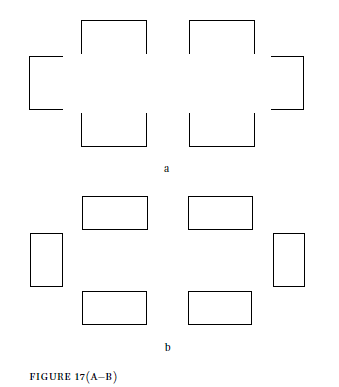

Seeing the outline of partially occluded yet complete rectangles in the upper and lower clips in figure 17(a) makes a rectangular surface, which is also brighter than the background, to appear above them. Although there is no physical property in the stimulation corresponding to the borders of the rectangular surface, nor any difference of reflectance between the regions that appear as either the overlying surface or the ground, this figure still appears with such a visible shape that it induces the stratification of the field. The modification in figure 17(b), namely closing the boundary of the clips, makes the conditions of perceptual completion vanish, and no mental representation can help in perceiving these ones as something other than segregated rectangles and disconnected pieces.

The experimental research into perception is carried out through artificial conditions in which the perceivable effects of phenomena such as perceptual completion are manipulated to discover the “logic” or the “grammar” of perception. For example, stimulation makes the occluding surfaces appear, but the form of the completed parts is not arbitrary. Therefore, the perceptual formation of the occluded parts is only constrained by the neighboring regions of the stimulation rather than caused by it (1991: 67). The visible parts in a scene must bring about the particular completion that is preferentially forced upon the subjects against all the possible forms of completion. If a controlled transformation is forced on them, one can observe that the form of the completed objects varies systematically and specify the underlying rules of perception.

Contrary to Rock (1983), Kanizsa intends the logic of perception as the self-enclosed collection of rules that are independent of those followed by reasoning or inferential problem solving (1985: 29). The autonomous phenomenological logic fulfils the same function as does grammar for language, and it accounts for the ordered and structured manner in which the world appears. This does not contradict the claim that perception has to be studied independently of the naive realism that identifies appearances with the material things of the common-sense world. To be sure, the grouping factors allow objects to appear unified, internally articulated, segregated from the ground regardless of whether they occur in the natural world or not (1985: 23-24). However, Kanizsa does not deny that perception is a primary cognitive function for understanding the world. He points out that it can be studied as a cognitive instrument used for an epistemological purpose or as an autonomous research object itself (1984: 38-39). In the latter case, the theory of perception has to account for how perception comes about rather than its accuracy and reliability. Yet once the autonomous grammar of perception is described, it might also account for the fact that the world does not appear disconnected or chaotic, as it would if perception consisted solely in collecting sense data or in recording physical properties.

Experimental phenomenology studies perception as an autonomous natural phenomenon. It is not a collection of descriptions or an inventory list of phenomena. It is an empirical science that aims at discovering the necessary functional connections among phenomena, specifying the conditions that favour or hinder their occurrence as well as influence their degrees of evidence. Of course, Kanizsa does not deny that perception depends on the brain’s neurobiology. However, he argues that perception science should have a suitable method to account for the specific features and rules that systematically characterize perception at a phenomenal level. Experimental phenomenology is not a conservative choice due to the incompleteness of the neurobiological data in a given phase of the scientific research. In fact, the features and rules of, and connections between, the repeatable content of phenomena maintain an observable validity that stands out against the variability of the theoretical posits, models and findings of other sciences.

Source: Calì Carmelo (2017), Phenomenology of Perception: Theories and Experimental Evidence, Brill.

10 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

10 Aug 2021

10 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021