Short-term financial decisions differ in two ways from long-term decisions such as the purchase of plant and equipment or the choice of capital structure. First, they generally involve short-lived assets and liabilities, and, second, they are usually easily reversed. Compare, for example, a 60-day bank loan with an issue of 20-year bonds. The bank loan is clearly a short-term decision. The firm can repay it two months later and be right back where it started. A firm might conceivably issue a 20-year bond in January and retire it in March, but it would be extremely inconvenient and expensive to do so. In practice, the bond issue is a long-term decision, not only because of the bond’s 20-year maturity but also because the decision to issue it cannot be reversed on short notice.

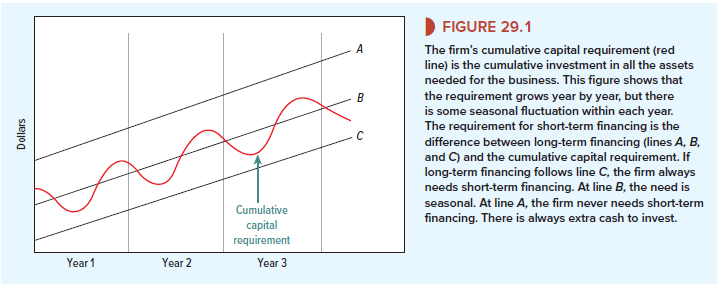

All businesses require capital—that is, money invested in plant, machinery, inventories, accounts receivable, and all the other assets it takes to run a business. These assets can be financed by either long-term or short-term sources of capital. Let us call the total investment the firm’s cumulative capital requirement. For most firms the cumulative capital requirement grows irregularly, like the wavy line in Figure 29.1. This line shows a clear upward trend as the firm’s business grows. But the figure also shows seasonal variation around the trend, with the capital requirement peaking late in each year. In addition, there would be unpredictable week-to-week and month-to-month fluctuations, but we have not attempted to show these in Figure 29.1.

When long-term financing does not cover the cumulative capital requirement, the firm must raise short-term capital to make up the difference. When long-term financing more than covers the cumulative capital requirement, the firm has surplus cash available. Thus the amount of long-term financing raised, given the capital requirement, determines whether the firm is a short-term borrower or lender.

Lines A, B, and C in Figure 29.1 illustrate this. Each depicts a different long-term financing strategy. Strategy A implies a permanent cash surplus, which can be invested in short-term securities. Strategy C implies a permanent need for short-term borrowing. Under B, which is probably the most common strategy, the firm is a short-term lender during part of the year and a borrower during the rest.

What is the best level of long-term financing relative to the cumulative capital requirement? It is hard to say. There is no convincing theoretical analysis of this question. We can make practical observations, however. First, most financial managers attempt to “match maturities” of assets and liabilities.[1] That is, they largely finance long-lived assets like plant and machinery with long-term borrowing and equity. Second, most firms make a permanent investment in net working capital (current assets less current liabilities). This investment is financed from long-term sources.

Current assets can be converted into cash more easily than long-term assets. So firms with large holdings of current assets enjoy greater liquidity. Of course, some of these assets are more rapidly converted into cash than others. Inventories are converted into cash only when the goods are produced, sold, and paid for. Receivables are more liquid; they become cash as customers pay their outstanding bills. Short-term securities can generally be sold if the firm needs cash on short notice and are therefore more liquid still.

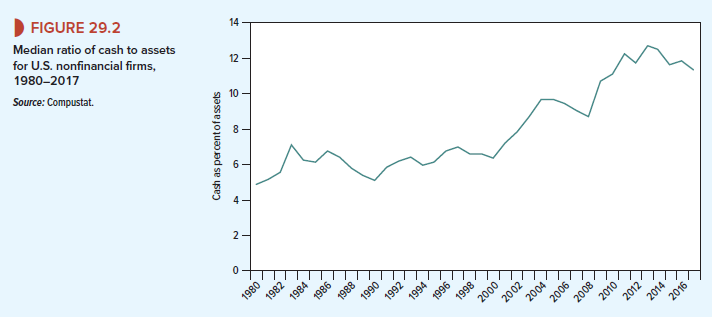

Whatever the motives for maintaining liquidity, they seem more powerful today than they used to be. You can see from Figure 29.2 that, particularly in the easy-money years before the financial crisis, firms in the United States increased their holdings of cash and marketable securities.

Some firms choose to hold more liquidity than others. For example, many high-tech companies, such as Intel and Cisco, hold huge amounts of short-term securities. On the other hand, firms in old-line manufacturing industries—such as chemicals, paper, or steel—manage with a far smaller reserve of liquidity. Why is this? One reason is that companies with rapidly growing profits may generate cash faster than they can redeploy it in new positive-NPV investments. This produces a surplus of cash that can be invested in short-term securities. Of course, companies faced with a growing mountain of cash may eventually respond by adjusting their payout policies. In Chapter 16, we saw how Apple sought to reduce its cash mountain by paying a special dividend and repurchasing its stock.

There are some advantages to holding a large reservoir of cash, particularly for smaller firms that face relatively high costs of raising funds on short notice. For example, biotech firms require large amounts of cash to develop new drugs. Therefore, these firms generally have substantial cash holdings to fund their R&D programs. If these precautionary reasons for holding liquid assets are important, we should find that small companies in relatively high-risk industries are more likely to hold large cash surpluses. A study by Tim Opler and others confirms that this is, in fact, the case.[2]

Financial managers of firms with a surplus of long-term financing and with cash in the bank don’t have to worry about finding the money to pay next month’s bills. The cash can help to protect the firm against a rainy day and give it the breathing space to make changes to operations. However, there are also drawbacks to surplus cash. Holdings of marketable securities are at best a zero-NPV investment for a taxpaying firm.3 Also, managers of firms with large cash surpluses may be tempted to run a less tight ship and may simply allow the cash to seep away in a succession of operating losses. For example, at the end of 2007, General Motors held $27 billion in cash and short-term investments. But shareholders valued GM stock at less than $14 billion. It seemed that shareholders realized (correctly) that the cash would be used to support ongoing losses and to service GM’s huge debts.

Pinkowitz and Williamson looked at the value that investors place on a firm’s cash and found that on average shareholders valued a dollar of cash at $1.20.4 They placed a particularly high value on liquidity in the case of firms with plenty of growth opportunities. At the other extreme, they found that when a firm was likely to face financial distress, a dollar of cash within the firm was often worth less than a dollar to the shareholders.5

Hi my loved one! I want to say that this article is amazing, nice written and come with almost all important infos. I would like to peer extra posts like this .