1. Ownership of the Corporation

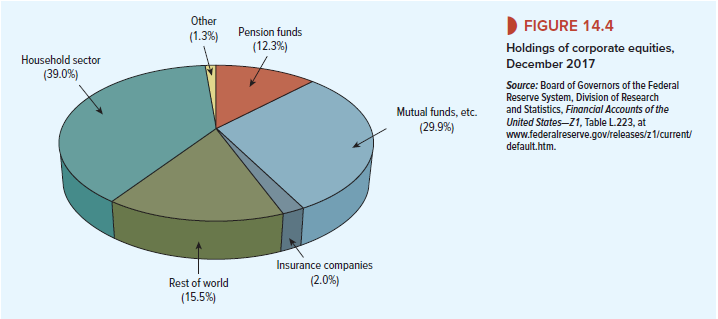

A corporation is owned by its common stockholders. You can see from Figure 14.4 that in the United States, 39% of this common stock is held directly by individual investors, and a similar proportion belongs to financial intermediaries such as mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies. Mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) hold 30% and pension funds a further 12%.4

But what do we mean when we say that these stockholders own the corporation? The answer is obvious if the company has issued no other securities. Consider the simplest possible case of a corporation financed solely by common stock, all of which is owned by the firm’s chief executive officer (CEO). This lucky owner-manager receives all the cash flows and makes all investment and operating decisions. She has complete cash-flow rights and also complete control rights.

These rights are split up and reallocated as soon as the company borrows money. If it takes out a bank loan, it enters into a contract with the bank promising to pay interest and eventually repay the principal. The bank gets a privileged, but limited, right to cash flows; the residual cash-flow rights are left with the stockholder. Thus common stock is a residual claim on the firm’s assets and cash flow.

The bank typically protects its claim by imposing restrictions on what the firm can or cannot do. For example, it may require the firm to limit future borrowing, and it may forbid the firm to sell off assets or to pay excessive dividends. The stockholders’ control rights are thereby limited. However, the contract with the bank can never restrict or determine all the operating and investment decisions necessary to run the firm efficiently. (No team of lawyers, no matter how long they scribbled, could ever write a contract covering all possible contingencies.5) The owner of the common stock retains the residual rights of control over these decisions. For example, she may choose to increase the selling price of the firm’s products, to hire temporary rather than permanent employees, or to construct a new plant in Miami Beach rather than Hollywood.

Ownership of the firm can of course change. If the firm fails to make the promised payments to the bank, it may be forced into bankruptcy. Once the firm is under the “protection” of a bankruptcy court, shareholders’ cash-flow and control rights are tightly restricted and may be extinguished altogether. Unless some rescue or reorganization plan can be implemented, the bank becomes the new owner of the firm and acquires the cash-flow and control rights of ownership. (We discuss bankruptcy in Chapter 32.)

No law of nature says residual cash-flow rights and residual control rights have to go together. For example, one could imagine a situation where the debtholder gets to make all the decisions. But this would be inefficient. Since the benefits of good decisions are felt mainly by the common stockholders, it makes sense to give them control over how the firm’s assets are used. Because they have the ultimate right of control and simultaneously have the residual cash flow entitlement, shareholders have an incentive to ensure that management maximizes their wealth.

Public corporations may be owned by tens of thousands of stockholders. The common stockholders in these corporations still have the residual rights over the cash flows and have the ultimate right of control over the company’s affairs. In practice, however, their control is limited to an entitlement to vote on appointments to the board of directors, and on other crucial matters such as the decision to merge. Many shareholders do not bother to vote. They reason that because they own so few shares, their vote will have little impact on the outcome. The problem is that, if all shareholders think in the same way, they cede effective control and management gets a free hand to look after its own interests.

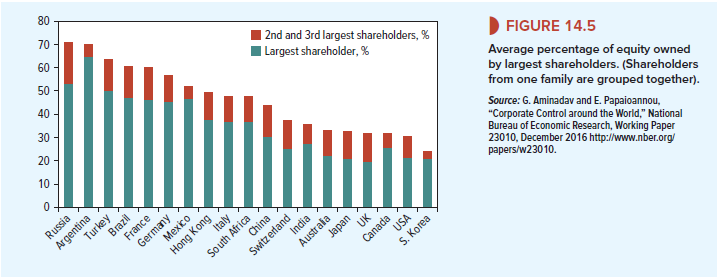

This free-rider problem was highlighted in a book written in 1932 by Berle and Means.[2] They warned of the emergence of a powerful class of managers that were insulated from outside pressure. Economists today are less convinced that managers enjoy the degree of liberty that Berle and Means envisaged. The majority of corporations have large shareholders who are prepared to challenge self-serving or incompetent managers. For example, Clifford Hold- erness found that 96% of a sample of U.S. public corporations have blockholders with at least 5% of the outstanding shares.[3] In many other countries blockholders are even more important. Look, for example, at Figure 14.5, which is taken from a comprehensive study of share ownership in 85 countries. You can see that in the United States, the largest shareholder owns, on average, just over 21% of the outstanding shares. In many of these cases, investors may take comfort from the fact that there are large shareholders with an incentive to keep a watchful eye on management. But the presence of blockholders is not always good news. In countries where the rule of law is weak, they may be able to profit at the expense of small shareholders, and their existence may be more a concern than a comfort. We will return to this topic of ownership when we review different governance systems in Chapter 33.

2. Voting Procedures

For many U.S. companies, the entire board of directors comes up for reelection each year. However, about 1 in 10 large companies have classified (or staggered) boards, where only a third of the directors are reelected annually. Proponents of such staggered boards argue that they help to insulate management from short-term pressure and allow the company to innovate and take risks. Shareholder activists, on the other hand, complain that staggered elections serve to entrench management since dissident shareholders must wait two years before they can gain majority representation on the board. Consequently, in recent years activists have successfully pressured many companies into declassifying their boards.

On many issues, a simple majority of shareholder votes cast is sufficient to carry the day, but the company charter may specify some decisions that require a supermajority of, say, 75% of those eligible to vote. For example, a supermajority vote is sometimes needed to approve a merger or a change to the charter. Such provisions have also attracted shareholder complaints that they help to entrench management and prevent worthwhile takeovers.

The issues on which stockholders are asked to vote are rarely contested, particularly in the case of large, publicly traded firms. Occasionally, there are proxy contests in which the firm’s existing management and directors compete with outsiders for effective control of the corporation. The odds in a proxy fight are stacked against the outsiders, for the insiders can get the firm to pay all the costs of presenting their case and obtaining votes.[4] But there are a growing number of activist investors who campaign for changes in management policy. If they can gather sufficient shareholder support, the corporation may get the message without incurring a proxy battle. For example, when activist investor Dan Loeb acquired a $3.5 billion stake in Nestle, the company moved to adopt most of his reforms.

3. Dual-Class Shares and Private Benefits

Usually, companies have one class of common stock and each share has one vote. Occasionally, however, a firm may have two classes of stock outstanding, which differ in their right to vote. For example, when Facebook made its first issue of common stock, the founders were reluctant to give up control of the company. Therefore, the company created two classes of shares. The A shares, which were sold to the public, had 1 vote each, while the B shares, which were owned by the founders, had 10 votes each. Both classes of shares had the same cash-flow rights, but they had different control rights.

When two classes of stock coexist, shareholders with the extra voting power may sometimes use it to toss out bad management or to force management to adopt policies that enhance shareholder value. But as long as both classes of shares have identical cash-flow rights, all shareholders benefit equally from such changes. So here is the question: If everyone gains equally from better management, why do shares with superior voting power typically sell at a premium? The only plausible reason is that there are private benefits captured by the owners of these shares. For example, the holder of a block of voting shares might prevent any challenge to his or her management position. The shares might have extra bargaining power in an acquisition. Or they might be held by another company, which could use its voting power and influence to secure a business advantage.

These private benefits of control seem to be much larger in some countries than others. For example, Tatiana Nenova has looked at a number of countries in which firms may have two classes of stock.[5] In the United States, the premium that an investor needed to pay to gain voting control amounted to only 2% of firm value, but in Italy it was over 29% and in Mexico it was 36%. It appears that in these two countries, majority investors are able to secure large private benefits.

Even when only one class of shares exists, minority stockholders may be at a disadvantage; the company’s cash flow and potential value may be diverted to management or to one or a few dominant stockholders holding large blocks of shares. In the United States, the law protects minority stockholders from exploitation, but minority stockholders in some countries may not fare so well.[6]

Financial economists sometimes refer to the exploitation of minority shareholders as tunneling; the majority shareholder tunnels into the firm and acquires control of the assets for himself. Let us look at tunneling Russian-style.

EXAMPLE 14.1 ● Raiding the Minority Shareholders

To grasp how the scam works, you first need to understand reverse stock splits. These are often used by companies with a large number of low-priced shares. The company making the reverse split simply combines its existing shares into a smaller, more convenient number of new shares. For example, the shareholders might be given two new shares in place of the three shares that they currently own. As long as all shareholdings are reduced by the same proportion, nobody gains or loses by such a move.

However, the majority shareholder of one Russian company realized that the reverse stock split could be used to loot the company’s assets. He therefore proposed that existing shareholders receive 1 new share in place of every 136,000 shares they currently held.[7]

Why did the majority shareholder pick the number “136,000”? Answer: Because the two minority shareholders owned less than 136,000 shares and therefore did not have the right to any shares. Instead, they were simply paid off with the par value of their shares, and the majority shareholder was left owning the entire company. The majority shareholders of several other companies were so impressed with this device that they also proposed similar reverse stock splits to squeeze out their minority shareholders.

Such blatant exploitation would not be permitted in the United States or in many other countries.

4. Equity in Disguise

Common stocks are issued by corporations, but a few equity securities are issued not by corporations but by partnerships or trusts. We will give some brief examples.

Partnerships Plains All American Pipeline LP is a master limited partnership that owns crude oil pipelines in the United States and Canada. You can buy “units” in this partnership on the New York Stock Exchange, thus becoming a limited partner in Plains All American. The most the limited partners can lose is their investment in the company.[8] In this and most other respects, the partnership units are just like the shares in an ordinary corporation. They share in the profits of the business and receive cash distributions (like dividends) from time to time.

Partnerships avoid corporate income tax; any profits or losses are passed straight through to the partners’ tax returns. But various limitations offset this tax advantage. For example, the law regards a partnership merely as a voluntary association of individuals; like its partners, it is expected to have a limited life. A corporation, on the other hand, is an independent legal “person” that can, and often does, outlive all its original shareholders.

Trusts and REITs Would you like to own a part of the oil in the Prudhoe Bay field on the north slope of Alaska? Just call your broker and buy a few units of the BP Prudhoe Bay Royalty Trust. BP set up this trust and gave it a royalty interest in production from BP’s share of the Prudhoe Bay revenues. As the oil is produced, each trust unit gets its share of the revenues.

This trust is the passive owner of a single asset: the right to a share of the revenues from BP’s Prudhoe Bay production. Operating businesses, which cannot be passive, are rarely organized as trusts, though there are exceptions, notably real estate investment trusts, or REITs (pronounced “reets”).

REITs were created to facilitate public investment in commercial real estate; there are shopping center REITs, office building REITs, apartment REITs, and REITs that specialize in lending to real estate developers. REIT “shares” are traded just like common stocks. The REITs themselves are not taxed, so long as they distribute at least 95% of earnings to the REITs’ owners, who must pay whatever taxes are due on the dividends. However, REITs are tightly restricted to real estate investment. You cannot set up a widget factory and avoid corporate taxes by calling it a REIT.

5. Preferred Stock

Usually, when investors talk about “stock” or “equity,” they are referring to common stock. But some companies also issue preferred stock, and this too forms part of its equity. Despite its name, preferred stock provides only a small part of most companies’ cash needs, and it will occupy less time in later chapters. However, it can be a useful method of financing in mergers and certain other special situations.

Like debt, preferred stock offers a series of fixed payments to the investor. The company can choose not to pay a preferred dividend, but in that case it may not pay a dividend to its common stockholders. Most issues of preferred are known as cumulative preferred stock. This means that the firm must pay all past preferred dividends before common stockholders get a cent. If the company does miss a preferred dividend, the preferred stockholders generally gain some voting rights, so that the common stockholders are obliged to share control of the company with the preferred holders. Directors are also aware that failure to pay the preferred dividend earns the company a black mark with investors, so they do not take such a decision lightly.

I don’t usually comment but I gotta admit thankyou for the post on this one : D.