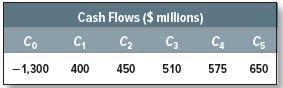

Suppose that the Swiss pharmaceutical company, Roche, is evaluating a proposal to build a new plant in the United States. To calculate the project’s net present value, Roche forecasts the following dollar cash flows from the project:

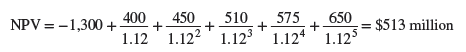

These cash flows are stated in dollars. So to calculate their net present value Roche discounts them at the dollar cost of capital. (Remember dollars need to be discounted at a dollar rate, not the Swiss franc rate.) Suppose this cost of capital is 12%. Then

To convert this net present value to Swiss francs, the manager can simply multiply the dollar NPV by the spot rate of exchange. For example, if the spot rate is CHF1.2/$, then the NPV in Swiss francs is

NPV in francs = NPV in dollars X CHF/$ = 513 X 1.2 = 616 million francs

Notice one very important feature of this calculation. Roche does not need to forecast whether the dollar is likely to strengthen or weaken against the Swiss franc. No currency forecast is needed because the company can hedge its foreign exchange exposure. In that case, the decision to accept or reject the pharmaceutical project in the United States is totally separate from the decision to bet on the outlook for the dollar. For example, it would be foolish for Roche to accept a poor project in the United States just because management is optimistic about the outlook for the dollar; if Roche wishes to speculate in this way it can simply buy dollars forward. Equally, it would be foolish for Roche to reject a good project just because management is pessimistic about the dollar. The company would do much better to go ahead with the project and sell dollars forward. In that way, it would get the best of both worlds.[1]

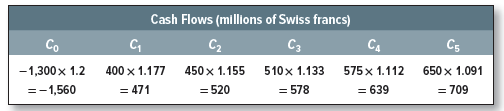

When Roche ignores currency risk and discounts the dollar cash flows at a dollar cost of capital, it is implicitly assuming that the currency risk is hedged. Let us check this by calculating the number of Swiss francs that Roche would receive if it hedged the currency risk by selling forward each future dollar cash flow.

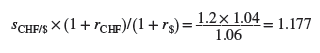

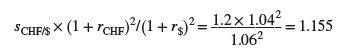

We need first to calculate the forward rate of exchange between dollars and francs. This depends on the interest rates in the United States and Switzerland. For example, suppose that the dollar interest rate is 6% and the Swiss franc interest rate is 4%. Then interest rate parity theory tells us that the one-year forward exchange rate is

Similarly, the two-year forward rate is

So, if Roche hedges its cash flows against exchange rate risk, the number of Swiss francs it will receive in each year is equal to the dollar cash flow times the forward rate of exchange:

These cash flows are in Swiss francs and therefore they need to be discounted at the risk- adjusted Swiss franc discount rate. Since the Swiss rate of interest is lower than the dollar rate, the risk-adjusted discount rate must also be correspondingly lower. The formula for converting from the required dollar return to the required Swiss franc return is[2]

![]()

In our example,

![]()

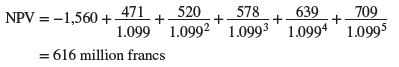

Thus the risk-adjusted discount rate in dollars is 12%, but the discount rate in Swiss francs is only 9.9%.

All that remains is to discount the Swiss franc cash flows at the 9.9% risk-adjusted discount rate:

Everything checks. We obtain exactly the same net present value by (1) ignoring currency risk and discounting Roche’s dollar cash flows at the dollar cost of capital and (2) calculating the cash flows in francs on the assumption that Roche hedges the currency risk and then discounting these Swiss franc cash flows at the franc cost of capital.

To repeat: When deciding whether to invest overseas, separate out the investment decision from the decision to take on currency risk. This means that your views about future exchange rates should NOT enter into the investment decision. The simplest way to calculate the NPV of an overseas investment is to forecast the cash flows in the foreign currency and discount them at the foreign currency cost of capital. The alternative is to calculate the cash flows that you would receive if you hedged the foreign currency risk. In this case, you need to translate the foreign currency cash flows into your own currency using the forward exchange rate and then discount these domestic currency cash flows at the domestic cost of capital. If the two methods don’t give the same answer, you have made a mistake.

When Roche analyzes the proposal to build a plant in the United States, it is able to ignore the outlook for the dollar only because it is free to hedge the currency risk. Because investment in a pharmaceutical plant does not come packaged with an investment in the dollar, the opportunity for firms to hedge allows for better investment decisions.

1. The Cost of Capital for International Investments

Roche should discount dollar cash flows at a dollar cost of capital. But how should a Swiss company like Roche calculate a cost of capital in dollars for an investment in the United States? There is no simple, consensus procedure for answering this question, but we suggest the following procedure as a start.

First you need to decide on the risk of a U.S. pharmaceutical investment to a Swiss investor. You could look at the betas of a sample of U.S. pharmaceutical companies relative to the Swiss market index.

Why measure betas relative to the Swiss index, while a U.S. counterpart such as Merck would measure betas relative to the U.S. index? The answer lies in Section 7-4, where we explained that risk cannot be considered in isolation; it depends on the other securities in the investor’s portfolio. Beta measures risk relative to the investor’s portfolio. If U.S. investors already hold the U.S. market, an additional dollar invested at home is just more of the same. But if Swiss investors hold the Swiss market, an investment in the United States can reduce their risk because the Swiss and U.S. markets are not perfectly correlated. That explains why an investment in the United States can be lower risk for Roche’s shareholders than for Merck’s shareholders. It also explains why Roche’s shareholders may be willing to accept a relatively low expected return from a U.S. investment.[3]

Suppose that you decide that the investment’s beta relative to the Swiss market is .8 and that the market risk premium in Switzerland is 7.4%. Then the required return on the project can be estimated as

Required return = Swiss interest rate + (beta X Swiss market risk premium)

= 4 + (.8 X 7.4) = 9.9

This is the project’s cost of capital measured in Swiss francs. We used it to discount the expected Swiss franc cash flows if Roche hedged the project against currency risk. We cannot use it to discount the dollar cash flows from the project.

To discount the expected dollar cash flows, we need to convert the Swiss franc cost of capital to a dollar cost of capital. This means running our earlier calculation in reverse:

![]()

In our example,

![]()

We used this 12% dollar cost of capital to discount the forecasted dollar cash flows from the project.

When a company measures risk relative to its domestic market as in our example, its managers are implicitly assuming that shareholders hold simply domestic stocks. That is not a bad approximation, particularly in the United States. Although U.S. investors can reduce their risk by holding an internationally diversified portfolio of shares, they generally invest only a small proportion of their money overseas. Why they are so shy is a puzzle. It looks as if they are worried about the costs of investing overseas, such as the extra costs involved in identifying which stocks to buy, or the possibility of unfair treatment by foreign companies or governments.

The world is getting smaller and “flatter,” however, and investors everywhere are increasing their holdings of foreign securities. Pension funds and other institutional investors have diversified internationally, and dozens of mutual funds have been set up for people who want to invest abroad. If investors throughout the world held the world portfolio, then costs of capital would converge. The cost of capital would still depend on the risk of the investment, but not on the domicile of the investing company. There is some evidence that for large U.S. firms it does not make much difference whether a U.S. or global beta is used. For firms in smaller countries, the evidence is not so clear-cut and sometimes a global beta may be more appropriate.[4]

I am not sure where you are getting your information, however good topic. I must spend a while learning much more or working out more. Thank you for fantastic information I was on the lookout for this info for my mission.

Its good as your other articles : D, thanks for putting up.