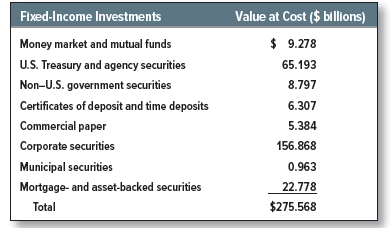

In December 2017, Apple was sitting on a $285 billion mountain of cash and fixed-income investments, amounting to about 70% of the company’s total assets. Of this sum, $9.5 billion was kept as cash and the remainder was invested as follows:

Apple’s massive investments in securities came from the torrent of free cash flow produced year after year by its operations. But its investments were interesting for at least two further reasons. First, Apple did not limit its investments to short-term securities. For example, it held $129.3 billion in long-term corporate bonds, included under “Corporate securities.” Second, U.S. tax law has pushed it to leave most of its investments on the books of its overseas subsidiaries. The 35% U.S. tax rate, which was higher than in most other countries, penalized U.S. corporations that repatriated foreign income. That is no longer the case, as we will soon see.

1. Tax Strategies

Most countries have territorial corporate income taxes: They tax income earned in their own countries but not outside their borders. The United States, on the other hand, has taxed its corporations’ worldwide income. (The U.S. switched to a territorial tax in 2018—more on that later.) Here is how the U.S. tax system used to work. Suppose that Apple’s Irish subsidiary earned profits worth $100,000 in 2017. The subsidiary paid $12,500 at Ireland’s 12.5% corporate tax rate. The U.S. rate in 2017 was 35%, one of the highest corporate tax rates in the world, but the Irish tax could be taken as a credit against U.S. tax. So Apple would have to pay an additional U.S. tax of .35 X 100,000 – 12,500 = $22,500 as soon as its Irish subsidiary sent the profits home. But why pay the extra tax? Why not just leave the money in Ireland? The U.S. tax on foreign income was paid only when income was repatriated.

That is exactly what Apple and other U.S. companies with profits abroad did. [The list of companies with the largest accumulations of overseas profits also includes Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), Cisco Systems, Pfizer, Abbott Labs, and Johnson & Johnson.] They paid other countries’ taxes, almost always at lower rates than 35%, but declined to bring the profits home. The amount of profits left abroad was estimated at more than $2 trillion in 2017.

Starting in 2018, the United States moved to a territorial system with a corporate tax rate reduced to 21%. U.S. corporations are no longer taxed on foreign income and no longer have an incentive to leave profits abroad in low-tax countries. But there is a one-time repatriation tax on profits accumulated abroad through the end of 2017. The tax rate is 15.5% on profits invested in cash and securities and 8% on profits invested in illiquid assets such as plant and equipment. The tax is payable in installments over the eight-year period 2018-2025. So Apple will have to pay tax on its accumulated overseas profits, although at a lower rate than if it had brought the profits home in 2017 or earlier.

In January 2018, Apple responded to the change in the tax law by announcing that it would pay U.S. tax of $38 billion to repatriate $252 billion of profits.

2. Investment Choices

Most companies do not have the luxury of such huge cash surpluses, but they also park any cash that is not immediately needed in short-term investments. The market for these investments is known as the money market. The money market has no physical marketplace. It consists of a loose collection of banks and dealers linked together by telephones or through the Web. But a huge volume of securities is regularly traded on the money market, and competition is vigorous.

Most large corporations manage their own money market investments, but small companies sometimes find it more convenient to hire a professional investment management firm or to put their cash into a money market fund. This is a mutual fund that invests only in low-risk, short-term securities.

The relative safety of money market funds has made them particularly popular at times of financial stress. During the credit crunch of 2008, fund assets mushroomed as investors fled from plunging stock markets. Then it was revealed that one fund, the Reserve Primary Fund, had incurred heavy losses on its holdings of Lehman Brothers’ commercial paper. The fund became only the second money market fund in history to “break the buck” by offering just 97 cents on the dollar to investors who cashed in their holdings. That week, investors pulled nearly $200 billion out of money market funds, prompting the government to offer emergency insurance to investors.

3. Calculating the Yield on Money Market Investments

Many money market investments are pure discount securities. This means that they don’t pay interest. The return consists of the difference between the amount you pay and the amount you receive at maturity. Unfortunately, it is no good trying to persuade the Internal Revenue Service that this difference represents capital gain. The IRS is wise to that one and will tax your return as ordinary income.

Interest rates on money market investments are often quoted on a discount basis. For example, suppose that three-month bills are issued at a discount of 5%. This is a rather complicated way of saying that the price of a three-month bill is 100 – (3/12) x 5 = 98.75. Therefore, for every $98.75 that you invest today, you receive $100 at the end of three months. The return over three months is 100/98.75-1 = .0127, or 1.27%. This is equivalent to an annual yield of 5.16%. Note that the return is always higher than the discount. When you read that an investment is selling at a discount of 5%, it is very easy to slip into the mistake of thinking that this is its return.[1]

4. Returns on Money Market Investments

When we value long-term debt, it is important to take account of default risk. Almost anything may happen in 30 years, and even today’s most respectable company may get into trouble eventually. Therefore, corporate bonds offer higher yields than Treasury bonds.

Short-term debt is not risk-free, but generally the danger of default is less for money market securities issued by corporations than for corporate bonds. There are two reasons for this. First, the range of possible outcomes is smaller for short-term investments. Even though the distant future may be clouded, you can usually be confident that a particular company will survive for at least the next month. Second, for the most part, only well-established companies can borrow in the money market. If you are going to lend money for just a few days, you can’t afford to spend too much time in evaluating the loan. Thus, you will consider only blue-chip borrowers.

Despite the high quality of money market investments, there are often significant differences in yield between corporate and U.S. government securities. Why is this? One answer is the risk of default. Another is that the investments have different degrees of liquidity or “moneyness.” Investors like Treasury bills because they are easily turned into cash on short notice. Securities that cannot be converted so quickly and cheaply into cash need to offer relatively high yields. During times of market turmoil investors may place a particularly high value on having ready access to cash. On these occasions the yield on illiquid securities can increase dramatically.

5. The International Money Market

In Chapter 24, we pointed out that there are two main markets for dollar bonds. There is the domestic market in the United States, and there is the eurobond market centered in London. There is also an international market for short-term dollar investments, which is known as the eurodollar market. Eurodollars have nothing to do with the euro, the currency of the European Monetary Union (EMU). They are simply dollars deposited in a bank in Europe.

Just as there is both a domestic U.S. money market and a eurodollar market, so there is both a domestic Japanese money market and a market in London for euroyen. So, if a U.S. corporation wishes to make a short-term investment in yen, it can deposit the yen with a bank in Tokyo or it can make a euroyen deposit in London. Similarly, there is both a domestic money market in the euro area as well as a money market for euros in London.16 And so on.

Major international banks in London lend dollars to one another at the London interbank offered rate (LIBOR). Similarly, they lend yen to each other at the yen LIBOR interest rate, and they lend euros at the euro interbank offered rate, or Euribor. These interest rates are used as a benchmark for pricing many types of short-term loans in the United States and in other countries. For example, a corporation in the United States may issue a floating-rate note with interest payments tied to dollar LIBOR.

If we lived in a world without regulation and taxes, the interest rate on a eurodollar loan would have to be the same as the rate on an equivalent domestic dollar loan. However, the international debt markets thrive because governments attempt to regulate domestic bank lending. When the U.S. government limited the rate of interest that banks in the United States could pay on domestic deposits, companies could earn a higher rate of interest by keeping their dollars on deposit in Europe. As these restrictions have been removed, differences in interest rates have largely disappeared.

In the late 1970s, the U.S. government was concerned that its regulations were driving business overseas to foreign banks and the overseas branches of American banks. To attract some of this business back to the States, the government in 1981 allowed U.S. and foreign

banks to establish international banking facilities (IBFs). An IBF is the financial equivalent of a free-trade zone; it is physically located in the United States, but it is not required to maintain reserves with the Federal Reserve and depositors are not subject to any U.S. tax.[2] However, there are tight restrictions on what business an IBF can conduct. In particular, it cannot accept deposits from domestic U.S. corporations or make loans to them.

6. Money Market Instruments

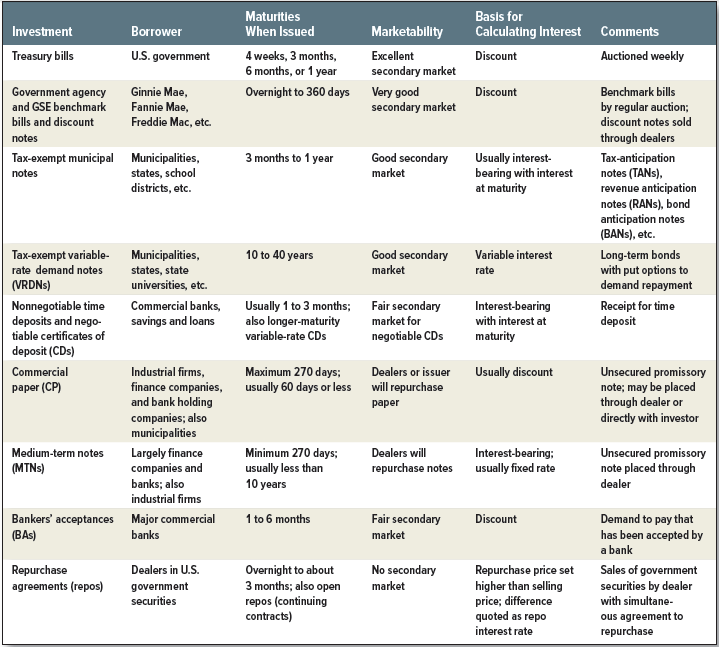

The principal money market instruments are summarized in Table 30.5. We describe each in turn.

U.S. Treasury Bills The first item in Table 30.5 is U.S. Treasury bills. These are usually issued weekly and mature in four weeks, three months, six months, or one year.[3] Sales are by a uniform-price auction. This means that all successful bidders are allotted bills at the same price.[4] You don’t have to participate in the auction to invest in Treasury bills. There is also an excellent secondary market in which billions of dollars of bills are bought and sold every day.

Federal Agency Securities “Agency securities” is a general term used to describe issues by government agencies and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Although most of this debt is not guaranteed by the U.S. government,[5] investors have generally assumed that the government would step in to prevent a default. That view was reinforced in 2008, when the two giant mortgage companies, the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) ran into trouble and were taken into government ownership.

Agencies and GSEs borrow both short and long term. The short-term debt consists of discount notes, which are similar to Treasury bills. They are actively traded and often held by corporations. These notes have traditionally offered somewhat higher yields than U.S. Treasuries. One reason is that agency debt is not quite as marketable as Treasury issues. In addition, unless the debt has an explicit government guarantee, investors have demanded an extra return to compensate for the (small?) possibility that the government would allow the agency to default.

Short-Term Tax-Exempts Short-term notes are also issued by states, municipalities, and agencies such as state universities and school districts.[6] These have one particular attraction—the interest is not subject to federal tax.[7] Of course, this tax advantage of municipal debt is usually recognized in its price. For many years, triple-A municipal debt yielded 10% to 30% less than equivalent Treasury debt.

Most tax-exempt debt is relatively low risk, and is often backed by an insurance policy, which promises to pay out if the municipality is about to default.[8] However, in the turbulent markets of 2008 even the backing of an insurance company did little to reassure investors, who worried that the insurers themselves could be in trouble. The tax advantage of “munis” no longer seemed quite so important.

Variable-Rate Demand Notes There is no law preventing firms from making short-term investments in long-term securities. If a firm has $1 million set aside for an income tax payment, it could buy a long-term bond on January 1 and sell it on April 15, when the taxes must be paid. However, the danger with this strategy is obvious. What happens if bond prices fall by 10% between January and April? There you are with a $1 million liability to the Internal Revenue Service, bonds worth only $900,000, and a very red face. Of course, bond prices could also go up, but why take the chance? Corporate treasurers entrusted with excess funds for short-term investments are naturally averse to the price volatility of long-term bonds.

One solution is to buy municipal variable-rate demand notes (VRDNs). These are longterm securities, whose interest payments are linked to the level of short-term interest rates. Whenever the interest rate is reset, investors have the right to sell the notes back to the issuer for their face value.[9] This ensures that on these reset dates the price of the notes cannot be less than their face value. Therefore, although VRDNs are long-term loans, their prices are very stable. In addition, the interest on municipal debt has the advantage of being tax-exempt. So a municipal variable-rate demand note offers a relatively safe, tax-free, short-term haven for your $1 million of cash.

Bank Time Deposits and Certificates of Deposit If you make a time deposit with a bank, you are lending money to the bank for a fixed period. If you need the money before maturity, the bank usually allows you to withdraw it but exacts a penalty in the form of a reduced rate of interest.

In the 1960s, banks introduced the negotiable certificate of deposit (CD) for time deposits of $1 million or more. In this case, when a bank borrows, it issues a certificate of deposit, which is simply evidence of a time deposit with that bank. If a lender needs the money before maturity, it can sell the CD to another investor. When the loan matures, the new owner of the CD presents it to the bank and receives payment.[10]

Commercial Paper and Medium-Term Notes As discussed in detail in Chapter 24, these consist of unsecured, short- and medium-term debt issued by companies on a regular basis.

Bankers’ Acceptances We saw earlier in the chapter how bankers’ acceptances (BAs) may be used to finance exports or imports. An acceptance begins life as a written demand for the bank to pay a given sum at a future date. Once the bank accepts this demand, it becomes a negotiable security that can be bought or sold through money-market dealers. Acceptances by the large U.S. banks generally mature in one to six months and involve very low credit risk.

Repurchase agreements, or repos, are effectively secured loans that are typically made to a government security dealer. They work as follows: The investor buys part of the dealer’s holding of Treasury securities and simultaneously arranges to sell them back again at a later date at a specified higher price.[11] The borrower (the dealer) is said to have entered into a repo; the lender (who buys the securities) is said to have a reverse repo.

Repos sometimes run for several months, but more frequently, they are just overnight (24-hour) agreements. No other domestic money-market investment offers such liquidity. Corporations can treat overnight repos almost as if they were interest-bearing demand deposits.

Suppose that you decide to invest cash in repos for several days or weeks. You don’t want to keep renegotiating agreements every day. One solution is to enter into an open repo with a security dealer. In this case, there is no fixed maturity to the agreement; either side is free to withdraw at one day’s notice. Alternatively, you may arrange with your bank to transfer any excess cash automatically into repos.

Auction-Rate Preferred Stock Common stock and preferred stock have an interesting tax advantage for corporations since firms pay tax on only 50% of the dividends that they receive. So, for each $1 of dividends received, the firm gets to keep 1 – (.50 x .21) = $.895. Thus the effective tax rate is only 10.5%. This is higher than the zero tax rate on the interest from municipal debt but much lower than the 21% rate that the company pays on other debt interest.

Suppose that you consider investing your firm’s spare cash in some other corporation’s preferred stock. The 10.5% tax rate is very tempting. On the other hand, you worry that the price of the preferred shares may change if long-term interest rates change. You can reduce that worry by investing in preferred shares whose dividend payments are linked to the general level of interest rates.27

Varying the dividend payment doesn’t quite do the trick because the price of the preferred stock could still fall if the risk increases. So, a number of companies added another wrinkle to floating-rate preferred. Instead of being tied rigidly to interest rates, the dividend can be reset periodically by means of an auction that is open to all investors. Investors can state the yield at which they are prepared to buy the stock. Existing shareholders who require a higher yield simply sell their stock to the new investors at its face value.

Auction-rate preferred stock is similar to a variable-rate demand note except that the issuer is not obliged to buy the stock back. If no new investors turn up at the auction, the existing shareholders are left holding the baby. That is what happened in 2008. Angry shareholders, who were unable to sell their stock, complained that banks had fraudulently marketed the issues as equivalent to cash, and many of the banks that originally handled the issues agreed to buy them back. Auction-rate preferred stock no longer seemed such a safe haven for cash.

I likewise think thence, perfectly written post! .