Mergers can be horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate. A horizontal merger is one that takes place between two firms in the same line of business. Most of the mergers listed in Table 31.1 are horizontal.

A vertical merger involves companies at different stages of production. The buyer expands back toward the source of raw materials or forward in the direction of the ultimate consumer. AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner is an example. It has been described as a combination of a “pipe” and a “content” company; it gives AT&T control over the entertainment content that it had previously passed through to its customers.

A conglomerate merger involves companies in unrelated lines of businesses. For example, the Indian Tata Group is a huge, widely diversified company. Its acquisitions have been as diverse as Eight O’Clock Coffee, Corus Steel, Jaguar Land Rover, the Ritz Carlton (Boston), and British Salt. No U.S. company is as diversified as Tata, but in the 1960s and 1970s, it was common in the United States for unrelated businesses to merge. Much of the action in the 1980s and 1990s came from breaking up the conglomerates that had been formed 10 to 20 years earlier.

With these distinctions in mind, we are about to consider motives for mergers—that is, reasons two firms may be worth more together than apart. We proceed with some trepidation. The motives, though they often lead the way to real benefits, are sometimes just mirages that tempt unwary or overconfident managers into takeover disasters. This was the case for AOL, which in 2000 spent a record-breaking $156 billion to acquire Time Warner. The aim was to create a company that could offer consumers a comprehensive package of media and information products. It didn’t work.

Even more embarrassing was Bank of America’s 2008 acquisition of mortgage lender Countrywide for $4 billion. The bank’s chief executive hailed the acquisition as a rare chance to become No. 1 in home loans. But after the housing bubble burst, the soured loans made by Countryside ended up costing Bank of America an estimated $40 billion in operating losses, fines, and compensation payments.

Many mergers that seem to make economic sense fail because managers cannot handle the complex task of integrating two firms with different production processes, accounting methods, and corporate cultures. The nearby box shows how these difficulties bedeviled the merger of three Japanese banks.

The value of most businesses depends on human assets—managers, skilled workers, scientists, and engineers. If these people are not happy in their new roles in the merged firm, the best of them will leave. Beware of paying too much for assets that go down in the elevator and out to the parking lot at the close of each business day. They may drive into the sunset and never return.

Consider the $38 billion merger in 1998 between Daimler-Benz and Chrysler. Although it was hailed as a model for consolidation in the auto industry, the early years were rife with conflicts between two very different cultures:

German management-board members had executive assistants who prepared detailed position papers on any number of issues. The Americans didn’t have assigned aides and formulated their decisions by talking directly to engineers or other specialists. A German decision worked its way through the bureaucracy for final approval at the top. Then it was set in stone. The Americans allowed midlevel employees to proceed on their own initiative, sometimes without waiting for executive-level approval. . . .

Cultural integration also was proving to be a slippery commodity. The yawning gap in pay scales fueled an undercurrent of tension. The Americans earned two, three, and, in some cases, four times as much as their German counterparts. But the expenses of U.S. workers were tightly controlled compared with the German system. Daimler-side employees thought nothing of flying to Paris or New York for a half-day meeting, then capping the visit with a fancy dinner and a night in an expensive hotel. The Americans blanched at the extravagance.

Nine years after acquiring Chrysler, Daimler threw in the towel and announced that it was offloading an 80% stake in Chrysler to a leveraged-buyout firm, Cerberus Capital Management. Daimler actually paid Cerberus $677 million to take Chrysler off its hands. Cerberus in return assumed about $18 billion in pension and employee health care liabilities and agreed to invest $6 billion in Chrysler and its finance subsidiary.

There are also occasions when the merger does achieve gains but the buyer nevertheless loses because it pays too much. For example, the buyer may overestimate the value of stale inventory or underestimate the costs of renovating old plant and equipment, or it may overlook the warranties on a defective product. Buyers need to be particularly careful about environmental liabilities. If there is pollution from the seller’s operations or toxic waste on its property, the costs of cleaning up will probably fall on the buyer.

Now we turn to the possible sources of merger synergies—that is, the possible sources of added value.

1. Economies of Scale

Many mergers are intended to reduce costs and achieve economies of scale. For example,when Heinz and Kraft Foods announced plans to merge in 2015, they forecast annual cost savings of $1.5 billion by the end of 2017. These savings would mostly come from economies of scale in the North American market, where there would be opportunities to shut down less efficient manufacturing facilities and reduce labor costs. Also, the larger combined sales would help the company to drive better bargains with retailers and restaurants.[2]

Achieving these economies of scale is the natural goal of horizontal mergers. But such economies have been claimed in conglomerate mergers, too. The architects of these mergers have pointed to the economies that come from sharing central services such as office management and accounting, financial control, executive development, and top-level management.[3]

2. Economies of Vertical Integration

Vertical mergers seek to gain control over the production process by expanding back toward the output of the raw material or forward to the ultimate consumer. One way to achieve this is to merge with a supplier or a customer.

Vertical integration facilitates coordination and administration. We illustrate via an extreme example. Think of an airline that does not own any planes. If it schedules a flight from Boston to San Francisco, it sells tickets and then rents a plane for that flight from a separate company. This strategy might work on a small scale, but it would be an administrative nightmare for a major carrier, which would have to coordinate hundreds of rental agreements daily. In view of these difficulties, it is not surprising that all major airlines have integrated backward, away from the consumer, by buying and flying airplanes rather than simply patronizing rent-a-plane companies.

When trying to explain differences in integration, economists often stress the problems that may arise when two business activities are inextricably linked. For example, production of components may require a large investment in highly specialized equipment. Or a smelter may need to be located next to the mine to reduce the costs of transporting the ore. It may be possible in such cases to organize the activities as separate firms operating under a long-term contract. But such a contract can never allow for every conceivable change in the way that the activities may need to interact. Therefore, when two parts of an operation are highly dependent on each other, it often makes sense to combine them within the same vertically integrated firm, which then has control over how the assets should be used.[4]

Nowadays the tide of vertical integration seems to be flowing out. Companies are finding it more efficient to outsource the provision of many services and various types of production. For example, back in the 1950s and 1960s, General Motors was deemed to have a cost advantage over its main competitors, Ford and Chrysler, because a greater fraction of the parts used in GM’s automobiles were produced in-house. By the 1990s, Ford and Chrysler had the advantage: They could buy the parts cheaper from outside suppliers. This was partly because the outside suppliers tended to use nonunion labor at lower wages. But it also appears that manufacturers have more bargaining power versus independent suppliers than versus a production facility that’s part of the corporate family. In 1998 GM decided to spin off Delphi, its automotive parts division, as a separate company. After the spin-off, GM continued to buy parts from Delphi in large volumes, but it negotiated the purchases at arm’s length.

3. Complementary Resources

Many small firms are acquired by large ones that can provide the missing ingredients necessary for the small firms’ success. The small firm may have a unique product but lack the engineering and sales organization required to produce and market it on a large scale. The firm could develop engineering and sales talent from scratch, but it may be quicker and cheaper to merge with a firm that already has ample talent. The two firms have complementary resources—each has what the other needs—and so it may make sense for them to merge. Also, the merger may open up opportunities that neither firm would pursue otherwise.

In recent years, many of the major pharmaceutical firms have faced the loss of patent protection on their more profitable products and have not had an offsetting pipeline of promising new compounds. This has prompted an increasing number of acquisitions of biotech firms. For example, in 2017 Bristol Myers acquired IFM Therapeutics, a start-up company with two pre-clinical immunotherapy programs. Bristol Myers calculated that IFM’s drugs would fit well with its own range of immunotherapy treatments. At the same time, IFM obtained the resources that it needed to bring its products to market.

4. Surplus Funds

Here’s another argument for mergers: Suppose that your firm is in a mature industry. It is generating a substantial amount of cash, but it has few profitable investment opportunities.

Ideally, such a firm should distribute the surplus cash to shareholders by increasing its dividend payment or repurchasing stock. Unfortunately, energetic managers are often reluctant to adopt a policy of shrinking their firm in this way. If the firm is not willing to purchase its own shares, it can instead purchase another company’s shares. Firms with a surplus of cash and a shortage of good investment opportunities often turn to mergers financed by cash as a way of redeploying their capital.

Some firms have excess cash and do not pay it out to stockholders or redeploy it by wise acquisitions. Such firms often find themselves targeted for takeover by other firms that propose to redeploy the cash for them. During the oil price slump of the early 1980s, many cash- rich oil companies found themselves threatened by takeover. This was not because their cash was a unique asset. The acquirers wanted to capture the companies’ cash flow to make sure it was not frittered away on negative-NPV oil exploration projects. We return to this free-cash- flow motive for takeovers later in this chapter.

5. Eliminating Inefficiencies

Cash is not the only asset that can be wasted by poor management. There are always firms with unexploited opportunities to cut costs and increase sales and earnings. Such firms are natural candidates for acquisition by other firms with better management. In some instances, “better management” may simply mean the determination to force painful cuts or realign the company’s operations. Notice that the motive for such acquisitions has nothing to do with benefits from combining two firms. Acquisition is simply the mechanism by which a new management team replaces the old one.

A merger is not the only way to improve management, but sometimes it is the only simple and practical way. Managers are naturally reluctant to fire or demote themselves, and stockholders of large public firms do not usually have much direct influence on how the firm is run or who runs it.[5]

If this motive for merger is important, one would expect to observe that acquisitions often precede a change in the management of the target firm. This seems to be the case. For example, Martin and McConnell found that the chief executive is four times more likely to be replaced in the year after a takeover than during earlier years.[6] The firms they studied had generally been poor performers; in the four years before acquisition their stock prices had lagged behind those of other firms in the same industry by 15%. Apparently many of these firms fell on bad times and were rescued, or reformed, by merger.

6. Industry Consolidation

The biggest opportunities to improve efficiency seem to come in industries with too many firms and too much capacity. These conditions can trigger a wave of mergers and acquisitions, which then force companies to cut capacity and employment and release capital for reinvestment elsewhere in the economy. For example, when U.S. defense budgets fell after the end of the Cold War, a round of consolidating takeovers followed in the defense industry. The consolidation was inevitable, but the takeovers accelerated it.

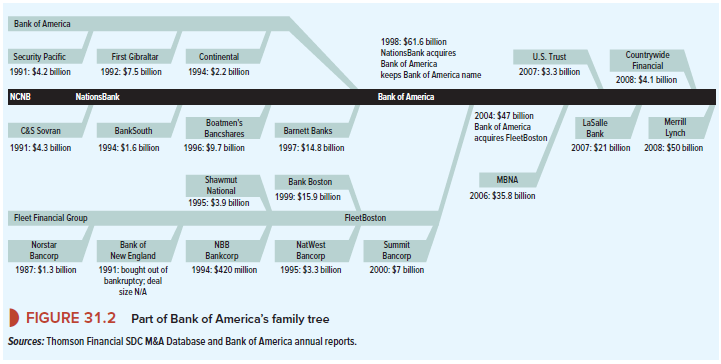

The banking industry is another example. During the financial crisis many banking mergers involved rescues of failing banks by larger and stronger rivals. But most earlier bank mergers involved successful banks that sought to achieve economies of scale. The United States entered the 1980s with far too many banks, largely as a result of outdated restrictions on interstate banking. As these restrictions eroded and communications and technology improved, small banks were swept up into regional or “super-regional” banks, and the number of banks declined from over 14,000 to little more than 5,000. For example, look at Figure 31.2, which shows some of the acquisitions by Bank of America and its predecessor companies. The main motive for these mergers was to reduce costs.

Europe also experienced a wave of bank mergers as companies sought to gain the financial muscle to compete in a Europe-wide banking market. These include the mergers of UBS and Swiss Bank Corp (1997), BNP and Banque Paribas (1998), Hypobank and Bayerische Vereinsbank (1998), Banco Santander and Banco Central Hispanico (1999), Unicredit and Capitalia (2007), and Commerzbank and Dresdner Bank (2009).

Those are yours alright! . We at least need to get these people stealing images to start blogging! They probably just did a image search and grabbed them. They look good though!

I’d have to examine with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a post that may make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to comment!