When one party is fully insured and cannot be accurately monitored by an insurance company with limited information, the insured party may take an action that increases the likelihood that an accident or an injury will occur. For example, if my home is fully insured against theft, I may be less diligent about locking doors when I leave, and I may choose not to install an alarm system. The possibility that an individual’s behavior may change because she has insurance is an example of a problem known as moral hazard.

The concept of moral hazard applies not only to problems of insur- ance, but also to problems of workers who perform below their capabilities when employers cannot monitor their behavior (“job shirking”). In general, moral hazard occurs when a party whose actions are unobserved affects the probability or magnitude of a payment. For example, if I have complete medical insurance coverage, I may visit the doctor more often than I would if my cover- age were limited. If the insurance provider can monitor its insurees’ behavior, it can charge higher fees for those who make more claims. But if the company can- not monitor behavior, it may find its payments to be larger than expected. Under conditions of moral hazard, insurance companies may be forced to increase pre- miums for everyone or even to refuse to sell insurance at all.

Consider, for example, the decisions faced by the owners of a warehouse valued at $100,000 by their insurance company. Suppose that if they run a $50 fire- prevention program for their employees, the probability of a fire is .005. Without this program, the probability increases to .01. Knowing this, the insurance company faces a dilemma if it cannot monitor the company’s decision to conduct a fire-prevention program. The policy that the insurance company offers cannot include a clause stating that payments will be made only if there is a fire-prevention program. If the program were in place, the company could insure the warehouse for a premium equal to the expected loss from a fire—an expected loss equal to .005 X $100,000 = $500. Once the insurance policy is purchased, however, the owners no longer have an incentive to run the program. If there is a fire, they will be fully compensated for their financial loss. Thus, if the insurance company sells a policy for $500, it will incur losses because the expected loss from the fire will be $1000 (.01 X $100,000).

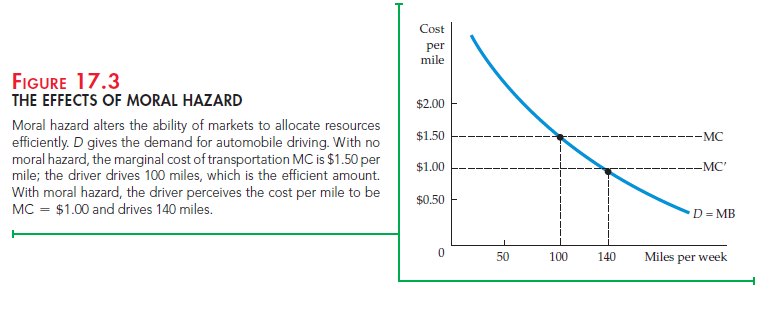

Moral hazard is a problem not only for insurance companies. It also alters the ability of markets to allocate resources efficiently. In Figure 17.3, for example, D gives the demand for automobile driving in miles per week. The demand curve, which measures the marginal benefits of driving, is downward sloping because some people switch to alternative transportation as the cost of driving increases. Suppose that initially, the cost of driving includes the insurance cost and that insurance companies can accurately measure miles driven. In this case, there is no moral hazard and the marginal cost of driving is given by MC. Drivers know that more driving will increase their insurance premiums and so increase their total cost of driving (the cost per mile is assumed to be constant). For example, if the cost of driving is $1.50 per mile (50 cents of which is insurance cost), drivers will go 100 miles per week.

A moral hazard problem arises when insurance companies cannot monitor individual driving habits, so that insurance premiums do not depend on miles driven. In that case, drivers assume that any additional accident costs that they incur will be spread over a large group, with only a negligible portion accruing to each of them individually. Because their insurance premiums do not vary with the number of miles that they drive, an additional mile of transportation will cost $1.00, as shown by the marginal cost curve MC’, rather than $1.50. The number of miles driven will increase from 100 to the socially inefficient level of 140.

Moral hazard not only alters behavior; it also creates economic inefficiency. The inefficiency arises because the insured individual perceives either the cost or the benefit of the activity differently from the true social cost or benefit. In the driving example of Figure 17.3, the efficient level of driving is given by the intersection of the marginal benefit (MB) and marginal cost (MC) curves. With moral hazard, however, the individual’s perceived marginal cost (MC’) is less than actual cost, and the number of miles driven per week (140) is higher than the efficient level at which marginal benefit is equal to marginal cost (100).

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

I think the admin of this web site is actually working hard in support of his website,

because

here every data is quality based data.

great as well as amazing blog. I really wish to thank you, for offering us far better information.

I have found good articles here. I adore your article. So ideal!

Pretty component to content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to say

that I get actually loved account your weblog posts.

Any way I will be subscribing on your augment and even I success you get admission to constantly

rapidly.