In some factor markets, individual buyers have buyer power that allows them to affect the prices they pay. Often this happens either when one firm is a monopsony buyer or there are only a few buyers, in which case each firm has some monopsony power. For example, we saw in Chapter 10 that automobile companies have monopsony power as buyers of parts and components. GM and Toyota, for example, buy large quantities of brakes, radiators, and other parts and can negotiate lower prices than those charged smaller purchasers. In other cases, there might be only two or three sellers of a factor and a dozen or more buyers, but each buyer nonetheless has bargaining power—it can negotiate low prices because it makes large and infrequent purchases and can play the sellers off against each other when bargaining over price.

Throughout this section, we will assume that the output market is perfectly competitive. In addition, because a single buyer is easier to visualize than several buyers who all have some monopsony power, we will restrict our attention at first to pure monopsony.

1. Monopsony Power: Marginal and Average Expenditure

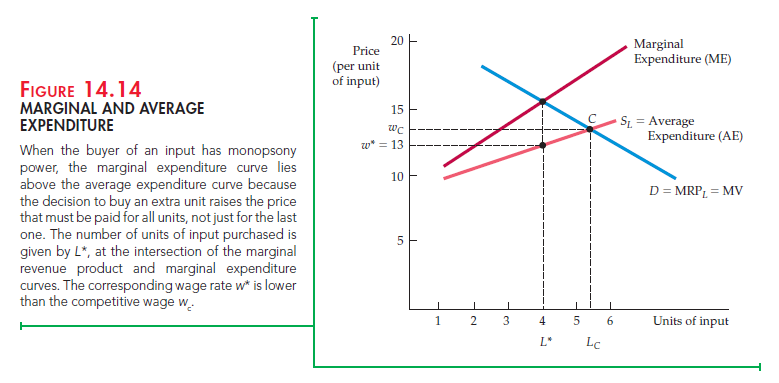

When you are deciding how much of a good to purchase, you keep increasing the number of units purchased until the additional value from the last unit pur- chased—the marginal value—is just equal to the cost of that unit—the marginal expenditure. In perfect competition, the price that you pay for the good—the average expenditure—is equal to the marginal expenditure. However, when you have monopsony power, the marginal expenditure is greater than the average expenditure, as Figure 14.14 shows.

The factor supply curve facing the monopsonist is the market supply curve, which shows how much of the factor suppliers are willing to sell as its price increases. Because the monopsonist pays the same price for each unit, the supply curve is its average expenditure curve. The average expenditure curve is upward sloping because the decision to buy an extra unit raises the price that must be paid for all units, not just the last one. For a profit-maximizing firm, however, the marginal expenditure curve is relevant in deciding how much to buy. The marginal expenditure curve lies above the average expenditure curve: When the firm increases the price of the factor to hire more units, it must pay all units that higher price, not just the last unit hired.

2. Purchasing Decisions with Monopsony Power

How much of the input should the firm buy? As we saw earlier, it should buy up to the point where marginal expenditure equals marginal revenue product. Here the benefit from the last unit bought (MRP) is just equal to the cost (ME). Figure 14.14 illustrates this principle for a labor market. Note that the monopsonist hires L* units of labor; at that point, ME = MRPL. The wage rate w* that workers are paid is given by finding the point on the average expenditure or supply curve with L* units of labor.

As we showed in Chapter 10, a buyer with monopsony power maximizes net benefit (utility less expenditure) from a purchase by buying up to the point where marginal value (MV) is equal to marginal expenditure:

MV = ME

For a firm buying a factor input, MV is just the marginal revenue product of the factor MRP. Thus, we have (as in the case of a competitive factor market)

Note from Figure 14.14 that the monopsonist hires less labor than a firm or group of firms with no monopsony power. In a competitive labor market, LC workers would be hired: At that level, the quantity of labor demanded (given by the marginal revenue product curve) is equal to the quantity of labor supplied (given by the average expenditure curve). Note also that the monopsonistic firm will be paying its workers a wage w* that is less than the wage wC that would be paid in a competitive market.

Monopsony power can arise in different ways. One source can be the specialized nature of a firm’s business. If the firm buys a component that no one else buys, it is likely to be a monopsonist in the market for that component. Another source can be a business’s location—it may be the only major employer within an area. Monopsony power can also arise when the buyers of a factor form a cartel to limit purchases of the factor, in order to buy it at less than the competitive price. (But as we explained in Chapter 10, this is a violation of the antitrust laws.)

Few firms in our economy are pure monopsonists. But many firms (or individuals) have some monopsony power because their purchases account for a large portion of the market. The government is a monopsonist when it hires volunteer soldiers or buys missiles, aircraft, and other specialized military equipment. A mining firm or other company that is the only major employer in a community also has monopsony power in the local labor market. Even in these cases, however, monopsony power may be limited because the government competes to some extent with other firms that offer similar jobs. Likewise, the mining firm competes to some extent with companies in nearby communities.

3. Bargaining Power

In some factor markets, there are a small number of sellers and a small number of buyers. In such cases, an individual buyer and an individual seller will negotiate with each other to determine a price. The resulting price might be high or low, depending on which side has more bargaining power.

The amount of bargaining power that a buyer or seller has is determined in part by the number of competing buyers and competing sellers. But it is also determined by the nature of the purchase itself. If each buyer makes large and infrequent purchases, it can sometimes play the sellers off against each other when negotiating a price and thereby amass considerable bargaining power.

An example of this kind of bargaining power occurs in the market for commercial aircraft. Airplanes are clearly key factor inputs for airlines, and airlines want to buy planes at the lowest possible prices. There are dozens of airlines, however, and only two major producers of commercial aircraft—Boeing and Airbus. One might think that as a result, Boeing and Airbus would have a considerable advantage when negotiating prices. The opposite is true. It is important to understand why.

Airlines do not buy planes every day, and they do not usually buy one plane at a time. A company like American Airlines will typically order new planes only every three or four years, and each order might be for 20 or 30 planes, at a cost of several billion dollars. As big as Boeing and Airbus are, this is no small purchase, and each seller will do all it can to win the order. American Airlines knows this and can use it to its advantage. If, for example, American is choosing between 20 new Boeing 787s or 20 new Airbus A380s (which are similar airplanes), it can play the two companies off against each other when negotiating a price. Thus if Boeing offers a price of, say, $300 million per plane, American might go to Airbus and ask it to do better. Whatever Airbus offers, American will then go back to Boeing and demand a bigger discount, claiming (truthfully or otherwise) that Airbus is offering large discounts. Then back to Airbus, back to Boeing, and so on, until American has succeeded in obtaining a large discount from one of the two companies.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this website. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and appearance. I must say you’ve done a amazing job with this. Additionally, the blog loads very fast for me on Safari. Exceptional Blog!