1. Event sampling

Event sampling is used when the behaviour of interest is discontinuous and low frequency, where you would miss the events if you didn’t observe continuously. The behaviour has to be specified exactly (making a monetary donation, engaging in conversation) so that it can be recorded on an observation schedule in a simple check-mark fashion.

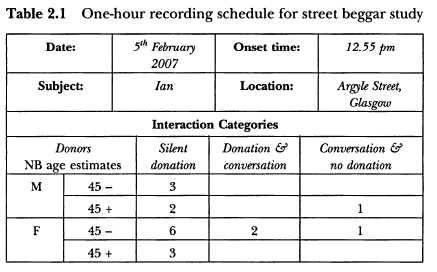

Now, my impression when passing these street beggars was that they didn’t get much custom: continuous observation showed a highly variable picture. But it also led me to expand the interaction categories as follows:

- ‘silent’ donation where nothing is said

- donation plus some conversation

- conversation but no donation.

Men were more likely to come into the first category. The last category, usually male, were different again; I came to describe them as ‘hangers on’ and some beggars had more of these than others.

In other words, even the simplest scheme requires amplification in practice. The point to watch is that it does not become too fragmented or unmanageable. For example, the ‘silent’ donation is a bit of a misnomer as I caught a hint of non-verbal communication now and then, usually eye contact, but too subtle for me to be sure of it. Note also that I was trying to identify unambiguous ‘chunks of behaviour’, not elusive fragments.

Defining the ‘events’

What the above discussion demonstrates is that defining a ‘simple’ event is not all that simple. I had thought initially in terms of a donation interaction but, once I had started observing, it became clear that that was not adequate. I had to define the events in terms of the kind of interaction. The interactions could have been further divided, for example in terms of different levels of conversation (the odd remark to a longer exchange). I decided against that on grounds of manageability: it is possible to create a recording schedule that is so exhaustive (exhausting?) as to be impractical. What I did was to observe one of the subjects of study for an hour and record each donating ‘event’. So I recorded frequency (how many times in the hour) and who donated (gender and my estimate of age 45+-). My first use of the developed schedule produced the results shown in Table 2.1.

The main point is that even when you try to keep it simple you have to develop your categories to be anywhere near adequate; and that there is a preceding phase of development where you try out your initial assumptions following a period of unstructured impressionistic observation. You might think that this preliminary stage should be sufficient to identify the categories. In fact, it is only by attempting to record these events that their limitations become apparent, because you don’t really observe in a focused way until you have the task of recording. This being ‘work in progress’, what is said here is neither a full account nor the last word – see Chapter 6 for a narrative account of this particular project.

2. Linked events

One of the virtues of continuous structured observation is that you can link events over time. It may be something as simple as noting the time someone joins a queue at an enquiry desk up to the time their enquiry is dealt with. Such a start-to-finish observation has multiple uses, for example ‘shopping behaviour’: a customer browsing a display up to the point of making a purchase. Other examples could be how long a child in a class has to wait to get a response from the teacher; how long people spend scanning an underground map, or reading a product instruction booklet before using the product and so on. This touches on the area of ‘experimental observation’ (see Chapter 3).

The limits of event sampling

The continuous recording of behavioural events works well when those events are not too frequent: it gets more difficult as the frequency increases, the main strain being on your capacity for sustained attention. This overload experience usually arises when observing several individuals in a group, such as a whole class of children. When the events are very high frequency – happening simultaneously and/or so often that continuous recording verges on the impossible – you have a number of options. These are:

- narrowing your category(ies) so you are observing only one or two types of behaviour clearly defined, i.e. picking them out of the flow

- carrying out time sampling where you observe, at intervals, for very short periods of time (a few seconds to a few minutes)

- constructing a narrative account – essentially unstructured, selective and, to a degree, impressionistic; this takes us out of the ‘structured’ frame entirely but there comes a point where any kind of specified behavioural sampling is not only impractical but inadequate.

Source: Gillham Bill (2008), Observation Techniques: Structured to Unstructured, Continuum; Illustrated edition.

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021