Retailing includes all the activities in selling goods or services directly to final consumers for personal, nonbusiness use. A retailer or retail store is any business enterprise whose sales volume comes primarily from retailing.

Any organization selling to final consumers—whether it is a manufacturer, wholesaler, or retailer—is doing retailing. It doesn’t matter how the goods or services are sold (in person, by mail, by telephone, by vending machine, or online) or where (in a store, on the street, or in the consumer’s home).

Retailing is a fast-moving, challenging industry. Consider the plight of Sears.2

SEARS Sears is a classic U.S. company. It was one of the first to sell goods through a mail-order catalog, and for more than 100 years, it was one of the strongest department store brands, associated with high-quality merchandise and responsive customer service. However, in the early 2000s, the company began facing financial difficulties, and to keep its earnings stable, it started aggressively selling assets and cutting costs. Customers began complaining about inattentive sales associates, disorganized sales racks, and stores in disrepair. Sears was spending only $2 to $3 per square foot in annual maintenance and repair of its stores, far less than the $6 to $8 per square foot spent by competitors Target and Walmart. “[T]hey weren’t keeping [their] promise. Consumers are pretty sophisticated, and they walked into these stores and it was the same old place . . . without the freshness, the excitement or the interactivity of the experience.” According to the ACS index of customer satisfaction, in 2012, Sears ranked 10th among 11 Department and Discount Stores. Given that same-store sales have declined for so many years, many feel Sears’ disillusioned customers may not be coming back.

At the same time, there are many retailing success stories. “Marketing Memo: Innovative Retail Organizations” highlights four examples of innovative retail organizations that have experienced market success in recent years. After reviewing the different types of retailers and some important characteristics of the modern retail marketing environment, we examine in detail the marketing decisions retailers make.

1. TYPES OF RETAILERS

Consumers today can shop for goods and services at store retailers, nonstore retailers, and retail organizations.

STORE RETAiLERS Perhaps the best-known type of store retailer is the department store. Japanese department stores such as Takashimaya and Mitsukoshi attract millions of shoppers each year and feature art galleries, restaurants, cooking classes, fitness clubs, and children’s playgrounds. The most important types of major store retailers are summarized in Table 18.1.

Different formats of store retailers will have different competitive and price dynamics. Discount stores, for example, historically have competed much more directly with each other than with other formats, though that is changing, as we’ll see below.3 Retailers also meet widely different consumer preferences for service levels and specific services. Specifically, they position themselves as offering one of four levels of service:

- Self-service—Self-service is the cornerstone of all discount operations. Many customers are willing to carry out their own “locate-compare-select” process to save money.

- Self-selection—Customers find their own goods, though they can ask for assistance.

- Limited service—These retailers carry more shopping goods and services such as credit and merchandise- return privileges. Customers need more information and assistance.

- Full service—Salespeople are ready to assist in every phase of the “locate-compare-select” process. Customers who like to be waited on prefer this type of store. The high staffing cost and many services, along with the higher proportion of specialty goods and slower-moving items, result in high-cost retailing.

NONSTORE RETAILING Although the overwhelming bulk of goods and services is sold through stores, nonstore retailing has been growing much faster than store retailing, especially given e-commerce and m-commerce as Chapter 17 outlined. Nonstore retailing falls into four major categories: direct marketing (which includes telemarketing and online selling), direct selling, automatic vending, and buying services:

- Direct marketing has roots in direct-mail and catalog marketing (Lands’ End, L.L.Bean); it includes telemarketing (1-800-FLOWERS), television direct-response marketing (HSN, QVC), and online shopping (Amazon.com, Autobytel.com). People are ordering a greater variety of goods and services from a wider range of Web sites. In the United States, online sales were estimated to be $225 billion in 2012, approaching 6 percent of total retail sales.4

- Direct selling, also called multilevel selling and network marketing, is a multibillion-dollar industry, with companies selling door to door or through at-home sales parties. Well-known in such one-to-one selling are Avon, Electrolux, and Southwestern Company of Nashville (Bibles). Tupperware and Mary Kay Cosmetics are sold one-to-many: A salesperson goes to the home of a host who has invited friends; the salesperson demonstrates the products and takes orders. Pioneered by Amway, the multilevel (network) marketing sales system works by recruiting independent businesspeople who act as distributors. The distributor’s compensation includes a percentage of sales made by those he or she recruits as well as earnings on his or her own direct sales to customers. These direct-selling firms, now finding fewer consumers at home, are developing multi-distribution strategies.

- Automatic vending offers a variety of merchandise, including impulse goods such as soft drinks, coffee, candy, newspapers, magazines, and other products such as hosiery, cosmetics, hot food, and paperbacks. Vending machines are found in factories, offices, large retail stores, gasoline stations, hotels, restaurants, and many other places. They offer 24-hour selling, self-service, and merchandise that is stocked to be fresh. With more than 5 million units, Japan has the highest per-capita coverage of vending machines in the world. You can buy everything from fresh eggs to pet rhinoceros beetles. Coca-Cola has close to 1 million machines there and annual vending sales of $50 billion—twice its U.S. figures.5

- Buying service is a storeless retailer serving a specific clientele—usually employees of large organizations— who are entitled to buy from a list of retailers that have agreed to give discounts in return for membership.

Without question, online nonstore retailing has been exploding and is taking many different forms. Consider the success of flash-sales Web sites such as Gilt.6

GILT During the recent recession, many designer brands found themselves with excess inventory they badly needed to move. Third-party “flash-sales” sites, offering deep discounts for luxury products and other goods for only a short period of time each day, allowed them to do so in a controlled manner less likely to hurt their brands. Modeled in part after France’s flash-sales pioneer Vente-Privee, Gilt was launched in November 2007 to sell fashionable women’s clothing from top designer labels for up to 60 percent off, but on a limited-time basis and only to those who joined the online site. Members were alerted of deals and their deadlines via e-mails that conveyed a sense of immediacy and urgency. Adding luxury brands such as Theory and Louis Vuitton, the firm grew to more than 8 million members and an estimated value of $1 billion. As the recession wound down, however, Gilt found itself challenged by dwindling inventory, growing competition from other sites, and its own aggressive expansion strategy, which included men’s clothes, kids’ products, home products, travel packages, and food. The company responded by focusing more on its core strength in women’s fashion and developing tighter relationships with customers via personalized e-mails to announce its sales.

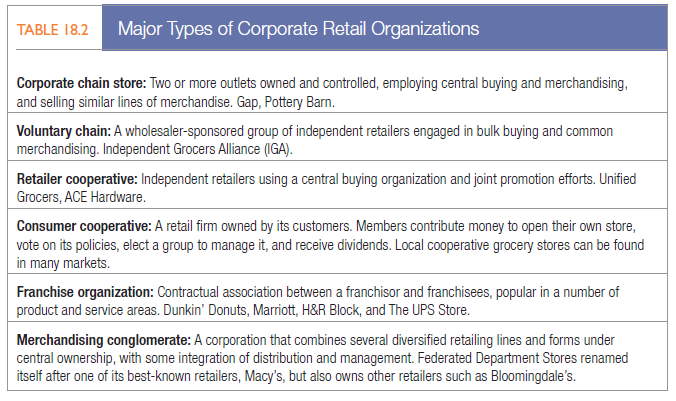

CORPORATE RETAILING AND FRANCHISING Although many retail stores are independently owned, an increasing number are part of a corporate retailing organization. These organizations achieve economies of scale, greater purchasing power, wider brand recognition, and better-trained employees than independent stores can usually gain alone. The major types of corporate retailing—corporate chain stores, voluntary chains, retailer and consumer cooperatives, franchises, and merchandising conglomerates—are described in Table 18.2.

Franchise businesses such as Hampton, Jiffy-Lube, Subway, Supercuts, 7-Eleven, and many others account for more than 10 percent of businesses with paid employees in the 295 industries for which franchising data are collected by the U.S. Census Bureau.7

In a franchising system, individual franchisees are a tightly knit group of enterprises whose systematic operations are planned, directed, and controlled by the operation’s innovator, called a franchisor. Franchises are distinguished by three characteristics:

- The franchisor owns a trade or service mark and licenses it to franchisees in return for royalty payments.

- The franchisee pays for the right to be part of the system. Start-up costs include rental and lease equipment and fixtures and usually a regular license fee. McDonald’s franchisees typically invest about $1.5 million in total start-up costs and fees. The franchisee then pays McDonald’s a certain percentage of sales plus a monthly rent.8

- The franchisor provides its franchisees with a system for doing business. McDonald’s requires franchisees to attend “Hamburger University” in Oak Brook, Illinois, for two weeks to learn how to manage the business. Franchisees must follow certain procedures in buying materials.9

Franchising benefits both parties. Franchisors gain the motivation and hard work of employees who are entrepreneurs rather than “hired hands,” the franchisees’ familiarity with local communities and conditions, and the enormous purchasing power of being a franchisor. Franchisees benefit from buying into a business with a well-known and accepted brand name. They find it easier to borrow money for their business from financial institutions, and they receive support in areas ranging from marketing and advertising to site selection and staffing.

Franchisees do walk a fine line between independence and loyalty to the franchisor. Some franchisors are giving their franchisees freedom to run their own operations, from personalizing store names to adjusting offerings and price. Great Harvest Bread believes in a “freedom franchise” approach that encourages its franchisee bakers to create new items for their store menus and to share with other franchisees if they are successful.10

2. MARKETING MEMO Innovative Retail Organizations

GameStop. Video game and entertainment software retailer GameStop has more than 6,600 convenient locations in malls and shopping strips all over the United States, staffed by hard-core gamers who like to connect with customers. The company boasts a trade-in policy that gives credit for an old game exchanged for a new one. To keep track of the activities of its 25 million customers, it also has a successful data-driven loyalty program, PowerUp Rewards, which offers reward points and allows members to manage their gaming interests with the online Game Library to showcase games members have had in the past, that they currently have, and that they wish they had.

Dick’s Sporting Goods. Dick’s Sporting Goods has grown from a single bait-and-tackle store in Binghamton, New York, into the largest U.S.-based full-line sporting goods retailer, with approximately 574 stores in 44 states. Part of its success springs from the interactive features of its stores. Customers can test golf clubs in indoor ranges, sample shoes on its footwear track, and shoot bows in its archery range. With an advertising tag line of “Every Season Starts at Dick’s,” the retailer is also emphasizing the fundamental goal of sports achievement and improvement to establish a stronger emotional connection with customers.

Lumber Liquidators. Lumber Liquidators is the largest hardwood flooring specialty retailer in the United States, with more than 345 locations. The company buys excess wood directly from lumber mills at a discount and stocks almost 350 kinds of flooring, about the same as Lowe’s and Home Depot. It sells at lower prices because it keeps operating costs down by cutting out the middlemen and locating stores in inexpensive locations. Lumber Liquidators also knows a lot about its customers, such as the fact that shoppers who request product samples have a 30 percent likelihood of buying within a month and that most tend to renovate one room at a time, not the entire home at once.

Net-a-Porter. London-based Net-a-Porter is an online luxury clothing and accessories retailer whose Web site combines the style of an fashion magazine with the thrill of a chic boutique. Seen by its loyal customers as an authoritative fashion voice, the company publishes its interactive magazine weekly and stocks more than 300 international brands, including Jimmy Choo, Alexander McQueen, Stella McCartney, Givenchy, and Marc Jacobs, as well as many up-and-comers. It ships to 170 countries and offers same-day delivery in London and Manhattan; the average order is $250. A new site, Mr. Porter, targets men.

Sources: GameStop. Steve Peterson, “GameStop Sees Targeted Marketing on the Rise,” www.thealistdaily.com, September 26, 2013; Jeanine Poggi, “GameStop Revamps Business to Ensure Success in a Digital Future,” Advertising Age, April 9, 2012; Chris Daniels, “GameStop CMO Sees CRM as Key,” Direct Marketing News, October 2011;

Devin Leonard, “GameStop Racks Up the Points,” Fortune, June 9, 2008, pp. 109-22; Dick’s Spoiling Goods. “Brand Genius: Lauren Hobart, Chief Marketing Officer, Dick’s Sporting Goods,” Adweek, September 23, 2013; Matt Townsend, “Dick’s Channels ‘Rudy’ in New Branding Strategy,” www.bloomberg.com, March 1, 2012; “Dick’s Sporting Goods Details Growth Strategy to Reach $10 Billion in Sales and 10.5% Operating Margin by the End of Fiscal 2017,” PR Newswire, August 3, 2013; Lumber Liquidators: Mark Heschmeyer, “Lumber Liquidators Planning to Spruce Up Retail Image, www.costar.com, January 30, 2013; Marilyn Much, “Lumber Liquidators’ New CEO Helps Drive Sales Surge,” Investor’s Business Daily, May 17, 2012; Helen Coster, “Hardwood Hero,” Forbes, November 30, 2009, pp. 60-62; Net-a-Porter. David Moth, “How Net-a-Porter Plans to Build on Its Mobile Success in 2013,” www.econsultancy.com, March 18, 2013; Christina Binkley, “Finding an Audience for Edgy Runway Styles,” Wall Street Journal, March 28, 2012; Paul Sonne, “Richemont to Buy Net-a-Porter,” Wall Street Journal, April 2, 2010; John Brodie, “The Amazon of Fashion,” Fortune, September 14, 2009, pp. 86-95.

3. THE MODERN RETAIL MARKETING ENVIRONMENT

The retail marketing environment is dramatically different today from what it was just a decade or so ago. Here we focus on two areas that have seen enormous change: competitive retail market structure and the role of technology.

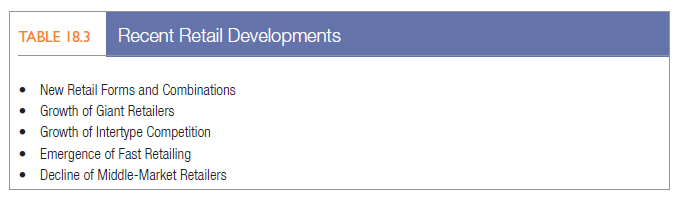

COMPETITIVE RETAIL MARKET STRUCTURE The retail market is very dynamic, and a number of new types of competitors and competition have emerged in recent years. Here are five important developments (see Table 18.3 for a summary).

- New Retail Forms and Combinations. To better satisfy customers’ need for convenience, a variety of new retail forms have emerged. Bookstores feature coffee shops. Gas stations include food stores. Loblaw’s Supermarkets have fitness clubs. Shopping malls and bus and train stations have peddlers’ carts in their aisles. Retailers are also experimenting with “pop-up” stores that let them promote brands to seasonal shoppers for a few weeks in busy areas. Pop-up stores are designed to create buzz often through interactive experiences. Internet companies such as Amazon.com and Google use pop-up stores as an easy way to establish a physical presence during holiday shopping seasons.11

- Growth of Giant Retailers. Through their superior information systems, logistical systems, and buying power, giant retailers such as Walmart are able to deliver good service and immense volumes of product to masses of consumers at appealing prices. They are crowding out smaller manufacturers that cannot deliver enough quantity and often dictate to the most powerful ones what to make, how to price and promote it, when and how to ship, and even how to improve production and management. Without these accounts, manufacturers would lose 10 percent to 30 percent of the market.

Some giant retailers are category killers that concentrate on one product category, such as pet food (PETCO), home improvement (Home Depot), or office supplies (Staples). Others are supercenters that combine grocery items with a huge selection of nonfood merchandise (Walmart). With their broad product assortments, reasonable prices, and convenient service, category killers wiped out many smaller specialty retailers. The rise of Amazon.com and other online retailers has nullified their advantages, however, and some category killers such as Borders, Circuit City, and Tweeter have even gone out of business.12

- Growth of Intertype Competition. One consequence of the growth of the supercenters is that department stores can’t worry just about other department stores—discount chains such as Walmart and Tesco are expanding into product areas such as clothing, health, beauty, and electrical appliances.13 Supermarkets also have to worry about these supercenters. Grocery products accounted for 56 percent of Walmart’s U.S. sales in 2012, up from 41 percent just six years ago. The reality is that different types of stores can all compete for the same consumers by carrying the same type of merchandise.

- Emergence of Fast Retailing. An important trend in fashion retailing in particular, but with broader implications, is the emergence of fast retailing. Here retailers develop completely different supply chain and distribution systems to allow them to offer consumers constantly changing product choices. Fast retailing requires thoughtful decisions in a number of areas, including new product development, sourcing, manufacturing, inventory management, and selling practices. As Chapter 12 described, consumers have been attracted to fast-fashion retailers such as H&M, Zara, Uniqlo, Top Shop, and Forever 21 because of the novelty, value, and fashion sense of their offerings and have made them successful. Critics, however, pan fast fashion for its planned obsolescence and the resulting disposability and waste.14

- Decline of Middle-Market Retailers. We can characterize the retail market today as hourglass or dog-bone shaped: Growth seems to be centered at the top (with luxury offerings from retailers such as Tiffany and Neiman Marcus) and at the bottom (with discount pricing from retailers such as Walmart and Dollar General). As discount retailers improve their quality and image, consumers have been willing to trade down. Target offers Phillip Lim, Jason Wu, and Missoni designs, and Kmart sells an extensive line of Joe Boxer underwear and sleepwear. At the other end of the spectrum, Coach converted 40 of its nearly 300 stores to a more upscale format that offers higher-priced bags and concierge services. Opportunities are scarcer in the middle, where once-successful retailers like JCPenney, Kohl’s, Sears, CompUSA, RadioShack, and Montgomery Ward have struggled or even gone out of business. Supermarket chains like Supervalu and Safeway have found themselves caught in the middle between the affluent appeal of chains like Whole Foods and the discount appeal of Aldi and Walmart. Compounding problems is the plight of the middle class—the 40 percent of U.S. consumers with annual incomes between $50,000 and $140,000—who have seen their buying power shrink due to slumping housing prices and stagnating incomes.15

ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY Technology is profoundly affecting the way retailers conduct virtually every facet of their business. Almost all now use technology to produce forecasts, control inventory costs, and order from suppliers, reducing the need to discount and run sales to clear out languishing products.

Technology is also directly affecting the consumer shopping experience inside the store. Electronic shelf labeling allows retailers to change price levels instantaneously at need.16 In-store programming on plasma TVs can run continual demonstrations or promotional messages. Retailers are experimenting with virtual shopping screens, audio/video presentations, and QR code integration.

For flagship stores in Taipei, Hong Kong, London, and Chicago, Burberry made “virtual rain” with a 360° film, as part of its digital “Burberry World Live” program showcasing its rain gear. The UK’s Marks & Spencer installed virtual mirrors in some of its stores so that, just as on its Web site, customers can see what an eye shadow or lipstick would look like for them without having to physically put it on.17

After encountering problems measuring store traffic in the aisles—GPS on shopping carts didn’t work because consumers tended to abandon their carts, and thermal imaging couldn’t tell the difference between babies and turkeys—bidirectional infrared sensors sitting on store shelves have proven successful. “Marketing Insight: The Growth of Shopper Marketing” describes the important role technology is taking in the aisles.

Retailers are also developing fully integrated digital communication strategies with well-designed Web sites, e-mails, search strategies, and social media campaigns. Social media are especially important for retailers during the holiday season when shoppers are seeking information and sharing successes. For the 2013 holiday season, Toys “R” Us focused on YouTube; Sears used Instagram and hosted holiday parties on Twitter; Target used Pinterest as well as six or seven other social media options.19 Beyond the holidays, many retailers are linking to customer photos supporting their brands on Instagram, Pinterest, and other sites to create social engagement.20

4. MARKETING INSIGH The Growth of Shopper Marketing

Buoyed by research suggesting that as many as 70 percent to 80 percent of purchase decisions are made inside the store, firms are increasingly recognizing the importance of influencing consumers at the point of purchase. Shopper marketing is the way manufacturers and retailers use stocking, displays, and promotions to affect consumers actively shopping for a product.

Where and how a product is displayed and sold can have a significant effect on sales. A strong proponent of shopper marketing, Procter & Gamble calls the store encounter the “first moment of truth” (product use and consumption are the second). P&G observed the power of displays in a Walmart project designed to boost sales of premium diapers such as Pampers. By creating the first baby center in which infant products—previously spread across the store—were united in a single aisle, the new shelf layout encouraged parents to linger longer and spend more money, increasing Pampers sales. Another successful promotion, this one for P&G’s Cover Girl cosmetics brand, tapped into a fashion trend for a “smoky eye” look by developing kits for Walmart and connecting with potential customers on Facebook with instructions, blogs, and a photo gallery.

Retailers are also using technology to influence customers as they shop. Some supermarkets are employing mobile phone apps or “smart shopping carts” that help customers locate items in the store, find out about sales and special offers, and pay more easily. One academic research study found that real-time spending feedback from a smart shopping cart stimulated budget shoppers to spend more (by buying more national brands) but led non-budget shoppers to spend less (by replacing national brands with store brands).

Kraft Foods spinoff Mondelez uses “smart shelf” technology by putting sensors on shelves near check-out that can detect the age and sex of a consumer and, by virtue of advanced analytics, target them with ads and promotions for a likely snack candidate on a video screen.18

Technology is also playing a crucial research role in the design of shopper marketing programs. Some retailers outfit their aisles with sensors or use video from security cameras or other means to monitor shoppers’ movements. Others use infrared goggles or wearable video cameras to record what test customers actually see. One finding was that many shoppers ignored products at eye level—the optimal location was between waist and chest level.

Other academic research found that unplanned purchases increased the more a product is touched, the longer a purchase is considered, the closer a customer is to the shelf, the fewer the shelf displays in sight, and the more quickly shoppers can reference external information. To capitalize on these findings, researchers recommend that retailers put Quick Response (QR) codes next to products to be scanned with smart phones. Even the simple act of touching a product on a tablet screen has been shown in research to increase purchase intent.

Sources: Megan Woolhouse, “Tablets Facilitate Impulse Shopping for Many,” Boston Globe, December 18, 2013; Elizabeth Dwoskin and Greg Bensinger, “Tracking Technology Sheds Light on Shopper Habits,” Wall Street Journal, December 9, 2013; S. Adam Brasel and Jim Gips, “Tablets, Touchscreens, and Touchpads: How Varying Touch Interfaces Trigger Psychological Ownership and Endowment” Journal of Consumer Psychology 24 (April 2014), pp. 226-33; Koert van Ittersum, Brian Wansink, Joost M. E. Pennings, and Daniel Sheehan, “Smart Shopping Carts: How Real-Time Feedback Influences Spending,” Journal of Marketing 77 (November 2013), pp. 21-36; Barry Silverstein, “Will Mondelez’s ‘Smart Shelves’ Change Retail or Just Add to Privacy Woes,” www.brandchannel.com, October 13, 2013; Noreen O’Leary, “Shopper Marketing Goes Mainstream,” Adweek, May 20, 2013, p. 19; Yanliu Huang, Sam K. Hui, J. Jeffrey Inman, and Jacob A. Suher, “Capturing the ‘First Moment of Truth’: Understanding Point-of-Purchase Drivers of Unplanned Consideration and Purchase,” MSI Report 12-101, www.msi.org, 2012; Pat Lenius, “P&G Leverages Facebook to Enhance Promotions in Walmart,” www.cpgmatters.com, November 2011; Venkatesh Shankar, “Shopper Marketing: Current Insights, Emerging Trends, and Future Directions,” MSI Relevant Knowledge Series Book, www.msi.org, 2011; Anthony Dukes and Yunchuan Liu, “In-Store Media and Distribution Channel Coordination,” Marketing Science 29 (January-February 2010), pp. 94-107; Richard Westlund, “Bringing Brands to Life: The Power of In-Store Marketing,” Special Advertising Supplement to Adweek, January 2010; Pierre Chandon, J. Wesley Hutchinson, Eric T. Bradlow, and Scott H. Young, “Does In-Store Marketing Work? Effects of the Number and Position of Shelf Facings on Brand Attention and Evaluation at the Point of Purchase,” Journal of Marketing Research 73 (November 2009), pp. 1-17; Michael C. Bellas, “Shopper Marketing’s Instant Impact,” Beverage World, November 2007, p. 18; Michael Freedman, “The Eyes Have It,” Forbes, September 4, 2006, p. 70.

5. MARKETING DECISIONS

With this new retail environment as a backdrop, we now examine retailers’ marketing decisions in some key areas: target market, channels, product assortment, procurement, prices, services, store atmosphere, store activities and experiences, communications, and location. We discuss private labels in the next section.

TARGET MARKET Until it defines and profiles the target market, the retailer cannot make consistent decisions about product assortment, store decor, advertising messages and media, price, and service levels. Whole Foods has succeeded by offering a unique shopping experience to a customer base interested in organic and natural foods.21

WHOLE FOODS MARKET In 284 stores in North America and the United Kingdom, Whole Foods creates celebrations of food. Its markets are bright and well staffed, and food displays are colorful, bountiful, and seductive. Whole Foods is the largest U.S. organic and natural foods grocer, offering more than 2,400 items in four lines of private-label products that add up to 11 percent of sales: the premium Whole Foods Market, Whole Kitchen, and Whole Market lines and the low- priced 365 Everyday Value line. Whole Foods also offers lots of information about its food. If you want to know, for instance, whether the chicken in the display case lived a happy, free-roaming life, you can get a 16-page booklet and an invitation to visit the farm in Pennsylvania where it was raised. For other help, you have only to ask a knowledgeable and easy-to-find employee. A typical Whole Foods has more than 200 employees, almost twice as many as Safeway. The company works hard to create an inviting store atmosphere with prices scrawled in chalk, cardboard boxes and ice everywhere, and other creative display touches to make the shopper feel at home. Its approach is working, especially for consumers who view organic and artisanal food as an affordable luxury. From 1991 to 2009, sales grew at a 28 percent compounded annual growth rate (CAGR). Although the recession hit the retailer hard, it did emerge with more double-digit growth.

Mistakes in choosing target markets can be costly. When historically mass-market jeweler Zales decided to chase upscale customers, it replaced one-third of its merchandise, dropping inexpensive, low-quality diamond jewelry for high- margin, fashionable 14-karat gold and silver pieces and shifting its ad campaign in the process. The move was a disaster. Zales lost many of its traditional customers without winning over the new customers it hoped to attract.22

To better hit their targets, retailers are slicing the market into ever-finer segments and introducing new lines of stores to exploit niche markets with more relevant offerings: Gymboree launched Janie and Jack, selling apparel and gifts for babies and toddlers; Hot Topic introduced Torrid, selling fashions for plus-sized teen girls; and Limited Brand’s Tween Brands began to sell lower-priced fashion to tween girls through its Justice stores and tween boys through its BROTHER shops.

CHANNELS Based on a target market analysis and other considerations we reviewed in Chapter 17, retailers must decide which channels to employ to reach their customers. Increasingly, the answer is multiple channels. Staples sells through its traditional retail brick-and-mortar channel, a direct-response Internet site, virtual malls, and thousands of links on affiliated sites.

As Chapter 17 also explained, channels should be designed to work together effectively. Although some experts predicted otherwise, catalogs have actually grown in an Internet world as more firms have revamped them to use them as branding devices and to complement online activity.23 Victoria’s Secret’s integrated multichannel approach of retail stores, catalog, and Internet has played a key role in its brand development.24

VICTORIA’S SECRET Victoria’s Secret, purchased by Limited Brands in 1982, has become one of the most identifiable brands in retailing through skillful marketing of women’s clothing, lingerie, and beauty products. Most U.S. women a generation ago did their underwear shopping in department stores and owned few items that could be considered “lingerie.” After witnessing women buying expensive lingerie as fashion items from small boutiques in Europe, Limited Brands founder Leslie Wexner felt a similar store model could work on a mass scale in the United States, though such a store format was unlike anything the average shopper would have encountered amid the bland racks at department stores. Wexner, however, had reason to believe U.S. women would relish the opportunity to have a European-style lingerie shopping experience with soft pink wallpaper, inviting fitting rooms, and attractive and attentive staff. “Women need underwear, but women want lingerie,” he observed. Wexner’s assumption proved correct: A little more than a decade after he bought the business, Victoria’s Secret’s average customer bought eight to 10 bras per year, compared with the national average of two. To enhance its upscale reputation and glamorous appeal, the brand is endorsed by high-profile supermodels in ads and televised fashion show extravaganzas. Victoria’s Secret sells through its stores, Web site, and catalog, mailing 325 million U.S. catalogs a year at a cost of $200 million. Web and catalog sales account for 25 percent of the company’s $5 billion in revenue. Overseas expansion is being led by “store within a store” beauty boutiques to reduce risk.

PRODUCT ASSORTMENT The retailer’s product assortment must match the target market’s shopping expectations in breadth and depth.25 A restaurant can offer a narrow and shallow assortment (small lunch counters), a narrow and deep assortment (delicatessen), a broad and shallow assortment (cafeteria), or a broad and deep assortment (large restaurant).

Destination categories may play a particularly important role because they have the greatest impact on where households choose to shop and how they view a particular retailer. A supermarket could be known for the freshness of its produce or for the variety and deals its offers in soft drinks and snacks.26

Identifying the right product assortment can be especially challenging in fast-moving industries such as technology or fashion. At one point, Urban Outfitters ran into trouble when it strayed from its “hip but not too hip” formula, embracing new styles too quickly.27 On the other hand, active and casual apparel retailer Aeropostale has succeeded by carefully matching its product assortment to its young teen needs.28

AEROPOSTALE Fourteen- to 17-year-olds, especially those on the young end, often want to look like other teens. So while Abercrombie and American Eagle might reduce the number of cargo pants on the sales floor, Aeropostale embraces this key reality of its target market and will keep an ample supply on hand at an affordable price. Staying on top of the right trends isn’t easy, but the company is among the most diligent of teen retailers when it comes to consumer research. In addition to running high-school focus groups and in-store product tests, it launched an online program that seeks the input of 10,000 of its best customers in creating new styles. An average of 3,500 participate in each of 20 tests a year. Aeropostale maintains control over its proprietary brands by designing, sourcing, marketing, and selling all its own merchandise. The company’s products can be purchased only in its own stores and online. Aeropostale has gone from a lackluster performer with only 100 stores to a powerhouse with more than 1,000 outlets in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Canada. One hundred new P.S. from Aeropostale stores target 4- to 12-year-olds with a strong value emphasis. Net sales totaled more than $2.6 billion in 2012, with net sales from e-commerce contributing more than $180 billion.

The real challenge begins after defining the store’s product assortment, when the retailer must develop a product- differentiation strategy. Here are some possibilities:

- Feature exclusive national brands not available at competing retailers. Saks might get exclusive rights to carry the dresses of a well-known international designer.

- Feature mostly private-label merchandise. Benetton and Gap design most of the clothes carried in their stores. Many supermarket and drug chains carry private-label merchandise.

- Feature blockbuster distinctive-merchandise events. Bloomingdale’s ran a month-long celebration for the Barbie doll’s 50th anniversary.

- Feature surprise or ever-changing merchandise. Off-price apparel retailer TJ Maxx offers surprise assortments of distress merchandise (goods the owner must sell immediately because it needs cash), overstocks, and closeouts sourced from more than 16,000 vendors and priced 20 percent to 60 percent below department and specialty store regular prices online and at its 1000-plus stores.

- Feature the latest or newest merchandise first. Zara excels in and profits from being first to market with appealing new looks and designs.

- Offer merchandise-customizing services. Harrods of London will make custom-tailored suits, shirts, and ties for customers in addition to ready-made menswear.

- Offer a highly targeted assortment. Lane Bryant carries goods for the larger woman. Brookstone offers unusual tools and gadgets for the person who wants to shop in a “toy store for grown-ups.”

Merchandise may also vary by geographical market. Macy’s and Ross Stores employ micro-merchandising and let managers select a significant percentage of store assortments.29

PROCUREMENT After deciding on the product-assortment strategy, the retailer must establish merchandise sources, policies, and practices. In the corporate headquarters of a supermarket chain, specialist buyers (sometimes called merchandise managers) are responsible for developing brand assortments and listening to presentations from their suppliers’ salespeople.

Retailers are rapidly improving their skills in demand forecasting, merchandise selection, stock control, space allocation, and display. They use sophisticated software to track inventory, compute economic order quantities, order goods, and analyze dollars spent on vendors and products. Supermarket chains use scanner data to manage their merchandise mix on a store-by-store basis.

Some stores are using radio frequency identification (RFID) systems made up of “smart” tags—microchips attached to tiny radio antennas—and electronic readers to facilitate inventory control and product replenishment. The smart tags can be embedded on products or stuck on labels, and when the tag is near a reader, it transmits a unique identifying number to its computer database. Coca-Cola and Gillette have used them to monitor inventory and track goods in real time as they move from factories to supermarkets to shopping baskets.30

ALDI’s unique procurement strategy emphasizes a constantly rotating group of select private label branded products.

Stores are using direct product profitability (DPP) to measure a product’s handling costs (receiving, moving to storage, paperwork, selecting, checking, loading, and space cost) from the time it reaches the warehouse until a customer buys it in the retail store. They learn to their surprise that the gross margin on a product often bears little relation to the direct product profit. Some high-volume products may have such high handling costs that they are less profitable and deserve less shelf space than low-volume products.

ALDI has differentiated itself on its innovative procurement strategy.31

ALDI The ALDI success story started in 1913 with a single small food market in Germany. Today, ALDI has two divisions, ALDI North and ALDI South, and 9,600 stores in 18 countries. While other food retailers carry thousands of products, ALDI’s product range is very narrow. With about 1,000 core products, dominated by ALDI-exclusive private labels, ALDI is very focused on products with high turnover, which it can source in high quantities at low prices. Logistics, weekly promotions, and store displays of products in transport boxes are designed to keep costs as low as possible in order to provide value. Customer perception of ALDI and its products has improved significantly over the years. High quality at low prices is the brand promise, and ALDI brands have reached top ratings in many independent product tests. To its suppliers, ALDI is known as a tough but reliable partner. Price negotiations are known to be very demanding. ALDI also expects suppliers to guarantee high standards of quality, and it constantly monitors quality throughout its whole supply chain.

PRICES Prices are a key positioning factor and must be set in relationship to the target market, product-and-service assortment mix, and competition.32 All retailers would like high turns x earns (high volumes and high gross margins), but the two don’t usually go together. Most retailers fall into the high-markup, lower-volume group (fine specialty stores) or the low-markup, higher-volume group (mass merchandisers and discount stores). Within each of these groups are further gradations.

At one end of the price spectrum is by-appointment-only Bijan on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, known as the most expensive store in the world. The original cost of its cologne was $1,500 for six ounces, and its suits are priced at $25,000, ties at $1,200, and socks at $100.33 At the other end of the scale, Target has skillfully combined a hip image with discount prices to offer customers a strong value proposition. It first introduced a line of products from world-renowned designers such as Michael Graves, Isaac Mizrahi, and Liz Lange and has continued to add high- profile names, such as singer Gwen Stefani to sell hip childrens clothes.34

Most retailers will put low prices on some items to serve as traffic builders (or loss leaders) or to signal their pricing policies.35 They will run storewide sales. They will plan markdowns on slower-moving merchandise. Shoe retailers, for example, expect to sell 50 percent of their shoes at the normal markup, 25 percent at a 40 percent markup, and the remaining 25 percent at cost. A stores average price level and discounting policies will affect its price image with consumers, but non-price-related factors such as store atmosphere and levels of service also matter.36

As Chapter 16 noted, some retailers such as Walmart have abandoned “sale pricing” in favor of everyday low pricing (EDLP). EDLP can lead to lower advertising costs, greater pricing stability, a stronger image of fairness and reliability, and higher retail profits. Supermarket chains practicing everyday low pricing can be more profitable than those practicing high-low sale pricing, but only in certain circumstances, such as when the market is characterized by many “large basket” shoppers who tend to buy many items on any one trip.37

All retailers are seeking to cut costs to improve margins. Some do so in an environmentally friendly way. Walmart has cut energy use by more than 50 percent and maintenance by more than 30 percent by painting store roofs white to reflect sunlight and reduce the use of air conditioning; capturing rain in storage tanks for flushing toilets and other uses that do not require drinking-quality water; and installing LED lights in parking lots.38

SERVICES Another differentiator is unerringly reliable customer service, whether face to face, across phone lines, or via online chat. Retailers must decide on the services mix to offer customers:

- Prepurchase services include accepting telephone and mail orders, advertising, window and interior display, fitting rooms, shopping hours, fashion shows, and trade-ins.

- Postpurchase services include shipping and delivery, gift wrapping, adjustments and returns, alterations and tailoring, installations, and engraving.

- Ancillary services include general information, check cashing, parking, restaurants, repairs, interior decorating, credit, rest rooms, and baby-attendant service.

Due to consumer complaints, many retailers have loosened up their returns policies in recent years. To reduce any possible impediment to sales and to improve their image with consumers, these firms are also eliminating restocking fees and extending return periods. Some policies have necessarily stayed in place, though, to combat frauds such as “wardrobing”—the practice of wearing and then returning clothing items.39 Gift cards remain another popular service offering; consumers spend more than $100 billion on cards annually.40

STORE ATMOSPHERE Every store has a look and a physical layout that makes it hard or easy to move around (see “Marketing Memo: Helping Stores to Sell”). Kohl’s floor plan is modeled after a racetrack loop and is designed to convey customers smoothly past all the merchandise in the store. It includes a middle aisle that hurried shoppers can use as a shortcut and yields higher spending levels than many competitors.41

Retailers must consider all the senses in shaping the customer’s experience. Varying the tempo of music affects average time and dollars spent in the supermarket—slow music can lead to higher sales. Bloomingdale’s uses different essences or scents in different departments: baby powder in the baby store; suntan lotion in the bathing suit area; lilacs in lingerie; and cinnamon and pine scent during the holiday season. Other retailers such as Victoria’s Secret and Juicy Couture use their own distinctive branded perfumes, which they also sell.42

STORE ACTIVITIES AND EXPERIENCES The growth of e-commerce has forced traditional brick-and- mortar retailers to respond. In addition to their natural advantages, such as products that shoppers can actually see, touch, and test; real-life customer service; and no delivery lag time for most purchases, stores also provide a shopping experience as a strong differentiator.

The store atmosphere should match shoppers’ basic motivations—if customers are likely to be in a task-oriented and functional mind-set, then a simpler, more restrained in-store environment may be better.43 On the other hand, some retailers of experiential products are creating in-store entertainment to attract customers who want fun and excitement.44 REI, seller of outdoor gear and clothing products, allows consumers to test climbing equipment on 25-foot or even 65-foot walls in the store and to try GORE-TEX raincoats under a simulated rain shower. Bass Pro Shops also offers rich customer experiences.45

BASS PRO SHOPS Bass Pro Shops, a retailer of outdoor sports equipment, caters to hunters, campers, fisherman, boaters, and outdoors fans of any type. Its Outdoor World superstores feature 200,000 square feet or more of giant aquariums, waterfalls, trout ponds, archery and rifle ranges, fly-tying demonstrations, indoor driving range and putting greens, and classes in everything from ice fishing to conservation—all free. Every department is set up to replicate the corresponding outdoor experience in support of product demonstrations and testing. During the summer, parents can

bring their kids to the free in-store Family Summer Camp with a host of activities in all departments. Bass Pro Shops builds a strong connection to its loyal customers from the moment they enter the store—through a turnstile designed to highlight that “they are entering an attraction, not just a retail space”—and are greeted by the irreverent sign saying “Welcome Fishermen, Hunters, and Other Liars.” One hundred and sixteen million people shopped at a Bass Pro Shop in 2012; the average customer drove more than 50 miles and stayed for more than two hours. The showroom in Missouri—the first and largest—is the number-one tourist destination in the state.

COMMUNICATIONS Retailers use a wide range of communication tools to generate traffic and purchases. They place ads, run special sales, issue money-saving coupons, send e-mail promotions, and run frequent- shopper-reward programs, in-store food sampling, and coupons on shelves or at check-out points. They work with manufacturers to design point-of-sale materials that reflect both their images. They time the arrival of their e-mails and design them with attention-grabbing subject lines and animation and personalized messages and advice.

Retailers are also using interactive and social media to pass on information and create communities around their brands. They study the way consumers respond to their e-mails, not only where and how messages are opened but also which words and images led to a click. Macy’s segments customers into more than a dozen groups and sends different e-mails for different products.46 Casual dining chain Houlihan’s social network site, HQ, gains immediate, unfiltered feedback from 10,500 invitation-only “Houlifan” customers in return for insider information about recipes and redesigns.47

With 15 percent of a retailer’s most loyal customers accounting for as much as half its sales, reward programs are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Consumers who choose to share personal information can receive discounts, secret or advance sales, exclusive offers, and store credits. CVS has 70 million loyalty club members who can use in-store coupon centers and receive coupons with their sales receipts.48

Many retailers are using Twitter to connect with customers and send ads to targeted groups.49 Some local retailers are using digital daily-deal services from Groupon, LivingSocial, and others, although recently many have soured on the approach due to a lack of profitability.50

LOCATION The three keys to retail success are often said to be “location, location, and location.” Department store chains, oil companies, and fast-food franchisers exercise great care in selecting regions of the country in which to open outlets, then particular cities, and then particular sites. Retailers can place their stores in the following locations:

- Central business districts. The oldest and most heavily trafficked city areas, often known as “downtown”

- Regional shopping centers. Large suburban malls containing 40 to 200 stores, typically featuring one or two nationally known anchor stores, such as Macy’s or Lord & Taylor or a combination of big-box stores such as PETCO, Payless Shoes, or Bed Bath & Beyond, and a great number of smaller stores, many under franchise operation.51

- Community shopping centers. Smaller malls with one anchor store and 20 to 40 smaller stores

- Shopping strips. A cluster of stores, usually in one long building, serving a neighborhood’s needs for groceries, hardware, laundry, shoe repair, and dry cleaning

- A location within a larger store. Smaller concession spaces taken by well-known retailers like McDonald’s, Starbucks, Nathan’s, and Dunkin’ Donuts within larger stores, airports, or schools or “store- within-a-store” specialty retailers located within a department store such as with Gucci within Neiman Marcus

- Stand-alone stores. Some retailers such as Kohl’s and JCPenney are avoiding malls and shopping centers in favor of freestanding storefronts so they are not connected directly to other retail stores.

In view of the relationship between high traffic and high rents, retailers must decide on the most advantageous locations for their outlets, using traffic counts, surveys of consumer shopping habits, and analysis of competitive locations.

6. MARKETING MEMO Helping Stores to Sell

In pursuit of higher sales volume, retailers are studying their store environments for ways to improve the shopper experience. Paco Underhill is a pioneer in that field and managing director of the retail consultant Envirosell, whose clients include McDonald’s, Starbucks, Estee Lauder, Gap, Burger King, CVS, and Wells Fargo. Using a combination of in-store video recording and observation tracking of as many as 40 different behaviors, Underhill and his colleagues study 50,000 people each year as they shop. He offers the following advice for fine-tuning retail space:

- Attract shoppers and keep them in the store. The amount of time shoppers spend in a store is perhaps the single most important factor in determining how much they buy. To increase shopping time, give shoppers a sense of community; recognize them in some way; make them comfortable, such as by providing chairs in convenient locations for spouses, children, or bags; and make the environment both familiar and fresh each time they come in.

- Honor the “transition zone.” On entering a store, people need to slow down and sort out the stimuli, which means they will likely be moving too fast to respond positively to signs, merchandise, or sales clerks in the zone they cross before making that transition. Make sure there are clear sight lines. Create a focal point for information within the store. Most right-handed people turn right upon entering a store.

- Avoid overdesign. Store fixtures, point-of-sales information, packaging, signage, and flat-screen televisions can combine to create a visual riot. Use crisp and clear signage—“Our Best Seller” or “Our Best Student Computer”—located where people feel comfortable stopping and facing the right way. Window signs, displays, and mannequins communicate best when angled 10 to 15 degrees to face the direction in which people are moving.

- Don’t make them hunt. Put the most popular products up front to reward busy shoppers and encourage leisurely shoppers to look more. At Staples, ink cartridges are one of the first products shoppers encounter after entering.

- Make merchandise available to the reach and touch. It is hard to overemphasize the importance of customers’ hands. A store can offer the finest, cheapest, sexiest goods, but if the shopper cannot reach them or pick them up, much of their appeal can be lost.

- Make kids welcome. If kids feel welcome, parents will follow. Take a 3-year-old’s perspective and make sure there are engaging sights at eye level. A virtual hopscotch pattern or dinosaur on the floor can turn a boring shopping trip for a child into a friendly experience.

- Note that men do not ask questions. Men always move faster than women do through a store’s aisles. In many settings, it is hard to get them to look at anything they had not intended to buy. Men also do not like asking where things are. If a man cannot find the section he is looking for, typically he will wheel about once or twice, then leave the store without ever asking for help.

- Remember women need space. A shopper, especially a woman, is far less likely to buy an item if her body is brushed, even lightly, by another customer when she is looking at a display. Keeping aisles wide and clear is crucial. With women playing an increasingly more significant buying role than men, designing retail experiences to satisfy them is crucial. Cleanliness, control, safety, and consideration are among the important retail decision factors for women.

- Make check-out easy. Be sure to have the right high-margin goods near cash registers to satisfy impulse shoppers. People love to buy candy when they check out—so satisfy their sweet tooth.

Sources: Paco Underhill, What Women Want: The Science of Female Shopping (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011); Paco Underhill, Call of the Mall: The Geography of Shopping (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004); Paco Underhill, Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999). See also Gloria Moss, “Time for Gatherers to Have More Clout in the Boardroom!,” Huffington Post, June 3, 2012; Brian Tarren, “Watchman,” Research, July 17, 2012; Susan Berfield, “Getting the Most Out of Every Shopper, BusinessWeek, February 9, 2009, pp. 45-46; Kenneth Hein, “Shopping Guru Sees Death of Detergent Aisle,” Brandweek, March 27, 2006, p. 11.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

I like this web site very much so much good information.