The difference between a corporate bond and a comparable Treasury bond is that the company has the option to default whereas the government supposedly doesn’t.[1] That default option is valuable. If you don’t believe us, think about whether (other things equal) you would prefer to be a shareholder in a company with limited liability or in a company with unlimited liability. Of course, you would prefer to have the option to walk away from your company’s debts. Unfortunately, every silver lining has its cloud, and the drawback to having a default option is that corporate bondholders expect to be compensated for giving it to you. That is why corporate bonds sell at lower prices and offer higher yields than government bonds.

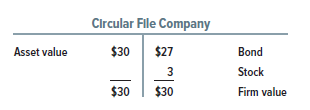

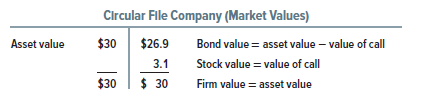

We can illustrate the nature of the default option by returning to the plight of Circular File Company, which we discussed in Chapter 18. Circular File borrowed $50 per share, but then fell on hard times, and the market value of its assets fell to $30. Circular’s bond and stock prices fell to $27 and $3, respectively. Thus Circular’s market-value balance sheet is:

If Circular’s debt were due and payable now, the firm could not repay the $50 it originally borrowed. It would default, leaving bondholders with assets worth $30 and shareholders with nothing. The reason that Circular stock has a market value of $3 is that the debt is not due immediately, but one year from now. A stroke of good fortune could increase firm value enough to pay off the bondholders in full, with something left over for the stockholders.

Circular File is not compelled to repay the debt at maturity. If the value of its assets is less than the $50 that it owes, it will choose to default on the debt and the bondholders will get to keep the assets. Circular’s bondholders have, in effect, bought a safe bond but, at the same time, given the shareholders a put option to sell the firm’s assets to the bondholders for the amount of the debt. The exercise price of the put is $50, the face value of the bond. If the value of the company’s assets when the bond matures is greater than $50, Circular will not exercise its option to default. If the assets’ value is less than $50, it will pay Circular to exercise its option and to hand over the assets to settle the debt.

Now you can see why bond traders, investors, and financial managers refer to default puts. When a firm defaults, its stockholders are, in effect, exercising their default put. The put’s value is the value of limited liability—the value of the stockholders’ right to walk away from their firm’s debts in exchange for handing over the firm’s assets to its creditors. In the case of Circular File, this option to default is extremely valuable because default is likely to occur. At the other extreme, the value of IBM’s option to default is trivial compared with the value of IBM’s assets. Default on IBM bonds is possible but extremely unlikely. Option traders would say that for Circular File, the put option is “deep in the money” because today’s asset value ($30) is well below the exercise price ($50). For IBM, the put option is far “out of the money” because the value of IBM’s assets greatly exceeds the amount of IBM’s debt.

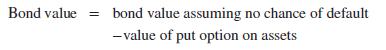

Valuing corporate bonds should be a two-step process:

The first step is easy: Calculate the bond’s value assuming no default risk. (Discount promised interest and principal payments at the rate offered by Treasuries.) The second step requires you to calculate the value of a put written on the firm’s assets, where the maturity of the put equals the maturity of the bond and the exercise price of the put equals the promised payment.

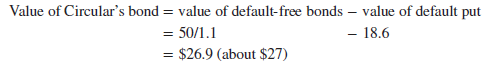

In Chapter 18, we assumed that the value of Circular’s bond was $27. Now we can see where that figure could have come from. Suppose that the standard deviation of the returns on Circular’s assets is 60% a year and that the risk-free interest rate is 10%. The current value of Circular’s assets is $30, and the exercise price of the default option is $50. If you enter these data into the Black-Scholes model, you find that the value of Circular’s default put is $18.6. You can now value its bond:

The value of Circular’s equity is equal to the value of its assets less the value of its debt. So the equity is worth about $3 (30 – 26.9 = $3.1).

Before you get too gung-ho about valuing the default option, we should warn you that, in practice, you would encounter complications that make the valuation of corporate bonds considerably more difficult than it sounds. For example, we assumed that Circular File is committed to making a single payment of $50 at the end of the year. But suppose, instead, that it has issued a 10-year bond that pays interest annually. In this case, there are 10 payments rather than just one. When each payment comes due, Circular has the option to make the coupon payment or to default. If it makes the payment, Circular obtains a second option to default when the second interest payment becomes due. The reward to making this payment is that the stockholders get a third put option, and so on. (This is an example of a compound put option.)

Of course, if the firm does not make any of these payments when due, bondholders take over, and stockholders are left with nothing. In other words, if Circular decides to exercise its default option, it gives up all subsequent default options.

Valuing the 10-year bond when it is issued is equivalent to valuing the first of the 10 options. But you cannot value the first option without valuing the nine that follow. Even this example understates the practical difficulties because large firms may have dozens of outstanding debt issues with different interest rates and maturities, and before the current debt matures, they may make further issues. Consequently, when bond traders evaluate a corporate bond, they do not immediately reach for their option calculator. They are more likely to start by identifying bonds with similar maturity and risk of default and look at the yield spreads offered by these bonds.

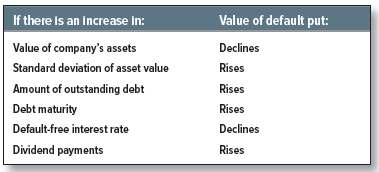

Valuing the default put may be challenging, but, now we know that limited liability is an option, we also know what the value of that option depends on. The following table shows how the value of the option to default depends on the underlying variables:

We have seen that corporate bonds sell for lower promised yields than comparable Treasury bonds. Can we explain the size of these yield spreads in terms of the default put that attaches to corporate bonds? Feldhutter and Schaefer believe that the answer is yes in the case of investment-grade bonds. For these bonds, they find that default risk can do a fairly good job of explaining the typical yield spread.[3] However, yields on junk bonds appear to be higher than their default experience would justify. It seems that investors in junk bonds demand additional yield to compensate for their relative lack of liquidity.

1. The Value of Corporate Equity

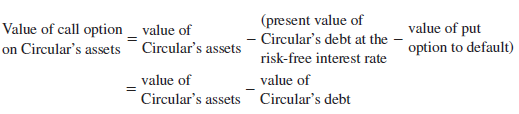

We saw in Chapter 20 that the value of a put option is identical to the value of a call option with the same exercise price, plus the present value of the exercise price, and less the value of the underlying asset. Think what this means for the value of Circular File’s default put:

Value of option to default = value of call option on Circular’s assets

+ present value of Circular’s debt at the risk-free interest rate

– value of Circular’s assets

If you twist this formula around, you get:

The expression on the right-hand side is simply the value of Circular’s equity. This tells us that you can think of Circular’s bondholders as effectively owning the company now, but the shareholders have the option to buy it back from them at the end of the year by paying off the debt. Thus, the balance sheet of Circular File can be expressed as follows:

2. A Digression: Valuing Government Financial Guarantees

When American Airlines declared bankruptcy in 2011, its pension plan had liabilities of $18.5 billion and assets of just $8.3 billion. But the 130,000 workers and retirees did not face a destitute old age. Their pensions were largely guaranteed by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC).9

Pension promises don’t always appear on the company’s balance sheet, but they are a longterm liability just like the promises to bondholders. The guarantee by the PBGC changes the pension promises from a risky liability to a safe one. If the company goes belly-up and there are insufficient assets to cover the pensions, the PBGC makes up most of the difference.

The government recognizes that the guarantee provided by the PBGC is costly. Thus, shortly after assuming the liability for the American Airlines plan, the PBGC calculated that the discounted value of payments on defaulted plans and those close to default amounted to $98 billion.

Unfortunately, these calculations ignore the risk that other firms in the future may fail and hand over their pension liability to the PBGC. To calculate the cost of the guarantee, we need to think about what the value of company pension promises would be without any guarantee:

Value of guarantee = value of guaranteed pensions

– value of pension promises without a guarantee

With the guarantee, the pensions are as safe as a promise by the U.S. government;[4] without the guarantee, the pensions are like an ordinary debt obligation of the firm. We already know what the difference is between the value of safe government debt and risky corporate debt. It is the value of the firm’s right to hand over the assets of the firm and to walk away from its obligations. Thus, the value of the pension guarantee is the value of this put option.

In a paper prepared for the Congressional Budget Office, Wendy Kiska, Deborah Lucas, and Marvin Phaup show how option pricing models can help to give a better measure of the cost to the PBGC of pension guarantees.[5] Their estimates suggest that the value of the PBGC’s guarantees was substantially higher than its published estimate.

The PBGC is not the only government body to provide financial guarantees. For example, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guarantees bank deposit accounts, the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program guarantees loans to students, the Small Business Administration (SBA) provides partial guarantees for loans to small businesses, and so on. The government’s liability under these programs is enormous. Fortunately, option pricing is leading to a better way to calculate their cost.

16 Jan 2018

25 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

23 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021