The year 2017 was not a happy one for telecom operator, Frontier Communications. Its share price fell by 85% over the year, and its 11% bonds maturing in 2025 were trading at 79% of face value, where they offered a yield to maturity of 15.8%. A naive investor who compared this figure with the 2% yield on Treasury bonds might have concluded that Frontier’s bonds were a wonderful investment. But the owner would earn a 15.8% return only if the company repaid the debt in full. By 2017, that was looking increasingly doubtful. The company had recorded some hefty losses and was on life support. It had nearly $18 billion of debt in issue and just over $3 billion of book equity. Because there was a significant risk that the company would default on its bonds, the expected yield was much less than 15.8%.

Corporate bonds, such as the Frontier Communications bond, offer a higher promised yield than government bonds, but do they necessarily offer a higher expected yield? We can answer this question with a simple numerical example. Suppose that the interest rate on one-year riskfree bonds is 5%. Backwoods Chemical Company has issued 5% notes with a face value of $1,000, maturing in one year. What will the Backwoods notes sell for?

If the notes are risk-free, the answer is easy—just discount principal ($1,000) and interest ($50) at 5%:

![]()

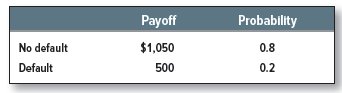

Suppose, however, that there is a 20% chance that Backwoods will default and that, if default does occur, holders of its notes receive half the face value of the notes, or $500. In this case, the possible payoffs to the noteholders are

The expected payment is .8($1,050) + .2($500) = $940.

We can value the Backwoods notes like any other risky asset, by discounting their expected payoff ($940) at the appropriate opportunity cost of capital. We might discount at the risk-free interest rate (5%) if Backwoods’s possible default is totally unrelated to other events in the economy. In this case, default risk is wholly diversifiable, and the beta of the notes is zero. The notes would sell for

![]()

An investor who purchased the notes for $895 would receive a promised yield of 17.3%:

![]()

That is, an investor who purchased the notes for $895 would earn a return of 17.3% if Backwoods does not default. Bond traders therefore might say that the Backwoods notes “yield 17.3%.” But the smart investor would realize that the notes’ expected yield is only 5%, the same as on risk-free bonds.

This, of course, assumes that the risk of default with these notes is wholly diversifiable so that they have no market risk. In general, risky bonds do have market risk (i.e., positive betas) because default is more likely to occur in recessions when all businesses are doing poorly. Suppose that investors demand a 3% risk premium and an 8% expected rate of return. Then the Backwoods notes will sell for 940/1.08 = $870 and offer a promised yield of (1,050/870) – 1 = .207, or 20.7%.

What Determines the Yield Spread?

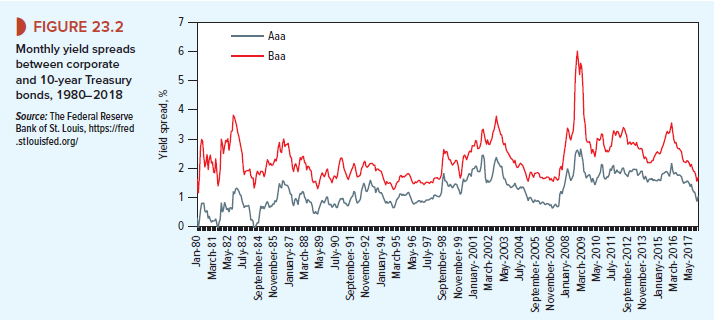

Figure 23.2 shows how the yield spread on U.S. corporate bonds varies with the bond’s risk. Bonds rated Aaa by Moody’s are the highest-grade bonds and are issued only by a few blue- chip companies. The promised yield on these bonds has on average been about 1% higher than the yield on Treasuries. Baa bonds are rated three notches lower; the yield spread on these bonds has averaged about 2%. At the bottom of the heap are high-yield or “junk” bonds. There is considerable variation in the yield spreads on junk bonds; a typical spread might be about 6% over Treasuries, but spreads can rocket skyward as companies fall into distress.

Remember these are promised yields and companies don’t always keep their promises. Many high-yielding bonds have defaulted, while some of the more successful issuers have called and paid off their debt, thus depriving their holders of the prospect of a continuing stream of high coupon payments.

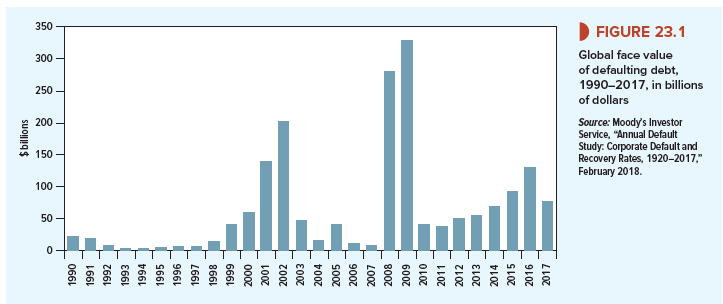

Figure 23.2 also shows that yield spreads can vary quite sharply from one year to the next, particularly for low-rated bonds. For example, they were unusually high in 2000-2002, and 2008-2009. Why is this? The main reason is that, as Figure 23.1 shows, these were periods when defaults were more likely. However, the fluctuations in spreads appear to be too large to be due simply to changing probabilities of default. It seems that there are occasions when investors are particularly reluctant to bear the risk of low-grade bonds and so scurry to the safe haven of government debt.1

To understand more precisely what the yield spread measures, compare these two strategies:

Strategy 1: Invest $1,000 in a floating-rate default-free bond yielding 9%.2

Strategy 2: Invest $1,000 in a comparable floating-rate corporate bond yielding 10%. At the same time, take out an insurance policy to protect yourself against the possibility of default. You pay an insurance premium of 1% a year, but in the event of default, you are compensated for any loss in the bond’s value.

Both strategies provide exactly the same payoff. In the case of strategy 2, you gain a 1% higher yield, but this is exactly offset by the 1% annual premium on the insurance policy. Why does the insurance premium have to be equal to the spread? Because, if it weren’t, one strategy would dominate the other and there would be an arbitrage opportunity. The law of one price tells us that two equivalent risk-free investments must cost the same.

Our example tells us how to interpret the spread on corporate bonds. It is equal to the annual premium that would be needed to insure the bond against default.3

By the way, you can insure corporate bonds; you do so with an arrangement called a credit default swap (CDS). If you buy a default swap, you commit to pay a regular insurance premium (or spread).4 In return, if the company subsequently defaults on its debt, the seller of the swap pays you the difference between the face value of the debt and its market value. For example, when American Airlines defaulted in 2011, its unsecured bonds were auctioned for 23.5% of face value. Thus, sellers of default swaps had to pay out 76.5 cents on each dollar of American Airlines’s debt that they had insured.

Credit default swaps proved very popular, particularly with banks that need to reduce the risk of their loan books. From almost nothing in 2000, the notional value of default swaps and related products had mushroomed to $62 trillion by the start of the financial crisis.5 Many of these default swaps were sold by monoline insurers, which specialize in providing services to the capital markets. The monolines had traditionally concentrated on insuring relatively safe municipal debt but had been increasingly prepared to underwrite corporate debt, as well as many securities that were backed by subprime mortgages. By 2008, insurance companies had sold protection on $2.4 trillion of bonds. As the outlook for many of these bonds deteriorated, investors began to question whether the insurance companies had sufficient capital to make good on their guarantees.

One of the largest providers of credit protection was AIG Financial Products, part of the giant insurance group, AIG, with a portfolio of more than $440 billion of credit guarantees. AIG’s clients never dreamed that the company would be unable to pay up: Not only was AIG triple-A rated, but it had promised to post generous collateral if the value of the insured securities dropped or if its own credit rating fell. So confident was AIG of its strategy that the head of its financial products group claimed that it was hard “to even see a scenario within any kind of realm of reason that would see us losing one dollar in any of these transactions.” But in September 2008, this unthinkable scenario occurred when the credit rating agencies downgraded AIG’s debt, and the company found itself obliged to provide $32 billion of additional collateral within the next 15 days. Had AIG defaulted, everyone who had bought a CDS contract from the company would have suffered large losses on these contracts. To save AIG from imminent collapse, the Federal Reserve stepped in with an $85 billion rescue package.

I’d have to test with you here. Which isn’t something I usually do! I get pleasure from studying a submit that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!