In some ways, financing decisions are more complex than investment decisions. The number of different securities and financing strategies is well into the hundreds (we have stopped counting). You will have to learn the major families, genera, and species. You will also need to become familiar with the vocabulary of financing. You will learn about red herrings, greenshoes, and bookrunners; behind each of these terms lies an interesting story.

There are also ways in which financing decisions are much easier than investment decisions. First, financing decisions do not have the same degree of finality as investment decisions. They are easier to reverse. Second, it’s harder to make money by smart financing strategies. The reason is that financial markets are more competitive than product markets. This means it is more difficult to find positive-NPV financing strategies than positive-NPV investment strategies.

When the firm looks at capital investment decisions, it does not assume that it is facing perfect, competitive markets. It may have only a few competitors that specialize in the same line of business in the same geographical area. And it may own some unique assets that give it an edge over its competitors. Often, these assets are intangible, such as patents, expertise, or reputation. All this opens up the opportunity to make superior profits and find projects with positive NPVs.

In financial markets, your competition is all other corporations seeking funds, to say nothing of the state, local, and federal governments that go to New York, London, Hong Kong, and other financial centers to raise money. The investors who supply financing are comparably numerous, and they are smart. Money attracts brains.

Competition is intense. Competition drives out easy profits for traders and investors who seek mispriced securities. If mispricing is rare, then it is reasonable to assume, at least as a starting point, that prices are right, or as right as human beings can get them.

When we suggest that stock or bond “prices are right,” we do not mean that they are stable. A price that is right today will change tomorrow when new information arrives. We only assume that prices incorporate all relevant information available to traders and investors at the time the prices are set. In other words, we assume that prices are set in efficient financial markets.

1. We Always Come Back to NPV

Financial managers separate investment and financing decisions. But the decisions to build a factory or issue a bond both involve valuation of an asset. The fact that you are buying a real asset (the factory) and selling a financial asset (the bond) doesn’t matter. In both cases you are concerned with the value of what is bought or sold.

For example, consider a new 10-year bond issue by GENX Corporation. The issue will raise $100 million for a new factory. The interest rate is 7%. GENX tried to negotiate a lower rate, but potential investors pointed out that 7% is the prevailing market interest rate on 10-year bonds issued by other companies with the same financial strength and bond rating as GENX. If GENX wants to sell the new bonds for $1,000 each, it will have to pay 7% interest on that $1,000.

Would you purchase the bond at this price? Before doing so, you decide to do a NPV calculation. You write out investment and interest payments.

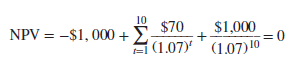

NPV =-$1,000 + PV of interest payments at 7% of $1,000 + PV of principal ($1,000 repaid in year 10)

What’s the discount rate—that is, what’s the opportunity cost of capital? It must be 7%. That’s the rate of return you can get on other bonds with the same maturity and risk. Therefore:

NPV = 0 because buying a GENX bond gives you the prevailing market rate of return.

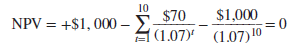

GENX’s CFO now decides to calculate the NPV of the bond issue for GENX. Her calculation is similar to yours, with signs reversed of course. Recall that the bond issue will raise $100 million. NPV of each bond that GENX sells is:

Again NPV = 0. The CFO is puzzled at first because 7% is less than the 15% rate of return she expects from the new factory. But she realizes that if the bond is fairly priced for investors, it must likewise be fairly priced for her company. She realizes that shareholder value comes from the factory (assuming that 15% exceeds the factory’s opportunity cost of capital), not from issuing ordinary bonds at the prevailing market interest rate. (Notice how the CFO has separated the investment and financing decisions. She has assigned a separate value to each.)

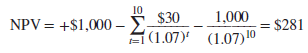

The bond issue would be positive NPV for GENX only if it could get an interest rate less than the prevailing market rate.1 That opportunity comes occasionally, but it almost always requires some kind of subsidy. Suppose New York State offers to lend at 3% if GENX locates the new factory in New York instead of New Jersey. That offer is positive-NPV:

Each bond that GENX can sell at the subsidized rate of interest has an NPV of $281.

Of course, you don’t need arithmetic to conclude that borrowing at 3% is a good deal when the market rate is 7%. But the NPV calculation tells you just how much that opportunity is worth.

If, on the other hand, GENX receives no subsidy but issues the bond at the prevailing market interest rate, then the “price is right,” and the transaction is zero-NPV for both GENX and the bond investors. In that case, positive NPVs must be sought on the asset side of the balance sheet.

Now we should consider the assumptions embedded in our example. We have ignored transaction costs, which we cover in Chapter 15. We have ignored taxes. We will see in Chapter 18 that interest payments create valuable tax deductions. But our most important assumption was to trust the bond market. We accepted the prevailing interest rate. We did not pause to ask whether that rate was too high or too low. We did not pause to forecast future interest rates. We assumed that the prevailing rate was completely up to date and incorporated all relevant information about all things—past, present and possible future events—that can determine interest rates and bond prices. In other words, we accepted the efficient market hypothesis for bonds.

In the next section we begin a review of the evidence for and against this hypothesis. We will focus on the stock market, but the hypothesis also applies to markets for bonds and other securities.

24 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

23 Jun 2021

23 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021