1. Private-Equity Partnerships

Figure 32.1 shows how a private-equity investment fund is organized. The fund is a partnership, not a corporation. The general partner sets up and manages the partnership. The limited partners put up almost all of the money. Limited partners are generally institutional investors, such as pension funds, endowments, and insurance companies. Wealthy individuals may also participate. The limited partners have limited liability, like shareholders in a corporation, but do not participate in management.

Once the partnership is formed, the general partners seek out companies to invest in. For example, we saw in Chapter 15 how venture capital partnerships look for high-tech start-ups or adolescent companies that need capital to grow. LBO funds, on the other hand, look for mature businesses with ample free cash flow that need restructuring. Some funds specialize in particular industries, for example, biotech, real estate, or energy. However, buyout funds like KKR’s and Cerberus’s look for opportunities almost anywhere.

The partnership agreement has a limited term, which is typically 10 years. The portfolio companies must then be sold and the proceeds distributed. So the general partners cannot reinvest the limited partners’ money. Of course, once a fund is proved successful, the general partners can usually go back to the limited partners, or to other institutional investors, and form another fund.

For example, Blackstone, one of the largest private-equity partnerships, formed six private-equity funds between 1987 and 2010. Then in 2015, it announced the formation of a new fund, Blackstone Capital Partners VII, with more than 250 limited partners. These investors committed to provide up to $18 billion.

The general partners of a private-equity fund get a management fee, usually 1% or 2% of capital committed.[1] plus a carried interest in 20% of any profits earned by the partnership. In other words, the limited partners get paid off first, but then get only 80% of any further returns. The general partners therefore have a call option on 20% of the partnership’s total future payoff, with an exercise price set by the limited partners’ investment.[2] You can see some of the advantages of private-equity partnerships:

- Carried interest gives the general partners plenty of upside. They are strongly motivated to earn back the limited partners’ investment and deliver a profit.

- Carried interest, because it is a call option, gives the general partners incentives to take risks. Venture capital funds take the risks inherent in start-up companies. Buyout funds amplify business risks with financial leverage.

- There is no separation of ownership and control. The general partners can intervene in the fund’s portfolio companies any time performance lags or strategy needs changing.

- There is no free-cash-flow problem: Limited partners don’t have to worry that cash from a first round of investments will be dribbled away in later rounds. Cash from the first round must be distributed to investors.

The foregoing are good reasons why private equity grew. But some contrarians say that rapid growth also came from irrational exuberance and speculative excess. These contrarian investors stayed on the sidelines and waited glumly (but hopefully) for the crash.

The popularity of private equity has also been linked to the costs and distractions of public ownership, including the costs of dealing with Sarbanes-Oxley and other legal and regulatory requirements. Many CEOs and CFOs feel pressured to meet short-term earnings targets. Perhaps they spend too much time worrying about these targets and about day-to-day changes in stock price. Perhaps going private avoids public investors’ “short-termism” and makes it easier to invest for the long run. But recall that for private equity, the long run is the life of the partnership, 8 or 10 years at most. General partners must find a way to cash out of the companies in the partnership’s portfolio. There are only two ways to cash out: an IPO or a trade sale to another company. Many of today’s private-equity deals will be future IPOs.

Thus, private-equity investors need public markets. The firms that seek divorce from public shareholders may well have to remarry them later.

2. Are Private-Equity Funds Today’s Conglomerates?

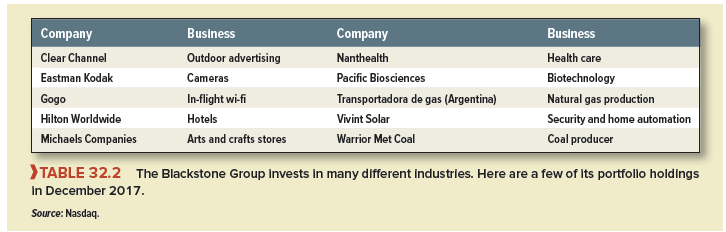

A conglomerate is a firm that diversifies across a number of unrelated businesses. Is Black- stone a conglomerate? Table 32.2, which lists some of Blackstone’s holdings, suggests that it is. Blackstone funds have invested in dozens of industries.

Does this mean that private equity today performs the tasks that public conglomerates used to do? Before answering that question, let’s take a brief look at the history of U.S. conglomerates.

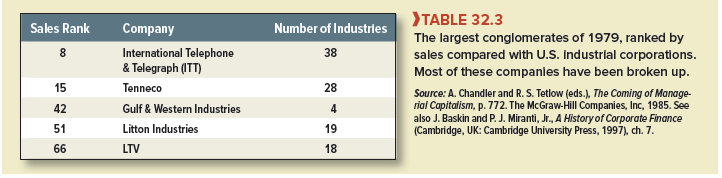

Conglomerates were fashionable in the 1960s when a merger boom created more than a dozen sprawling conglomerates. Table 32.3 shows that by the 1970s, some of these conglomerates had achieved amazing spans of activity. The largest conglomerate, ITT, was operating in 38 different industries and ranked eighth in sales among U.S. corporations.

Most of these conglomerates were broken up in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1995 ITT, which had already sold or spun off several businesses, split what was left into three separate firms. One acquired ITT’s interests in hotels and gambling; the second took over ITT’s automotive parts, defense, and electronics businesses; and the third specialized in insurance and financial services.

What advantages were claimed for the conglomerates of the 1960s and 1970s? First, diversification across industries was supposed to stabilize earnings and reduce risk. That’s hardly compelling because shareholders can diversify much more efficiently on their own.

Second, a widely diversified firm can operate an internal capital market. Free cash flow generated by divisions in mature industries (cash cows) can be funneled within the company to those divisions (stars) with plenty of profitable growth opportunities. Consequently, there is no need for fast-growing divisions to raise finance from outside investors.

There are some good arguments for internal capital markets. The company’s managers probably know more about its investment opportunities than outside investors do, and transaction costs of issuing securities are avoided. Nevertheless, it appears that attempts by conglomerates to allocate capital investment across many unrelated industries were more likely to subtract value than add it. Trouble is, internal capital markets are not really markets but combinations of central planning (by the conglomerate’s top management and financial staff) and intracompany bargaining. Divisional capital budgets depend on politics as well as pure economics. Large, profitable divisions with plenty of free cash flow may have the most bargaining power; they may get generous capital budgets while smaller divisions with good growth opportunities are reined in.

Internal Capital Markets in the Oil Business Misallocation in internal capital markets is not restricted to pure conglomerates. For example, Lamont found that when oil prices fell by half in 1986, diversified oil companies cut back capital investment in their non-oil divisions. The non-oil divisions were forced to “share the pain,” even though the drop in oil prices did not diminish their investment opportunities. The Wall Street Journal reported one example:

Chevron Corp. cut its planned 1986 capital and exploratory budget by about 30% because of the plunge in oil prices . . . . A Chevron spokesman said that the spending cuts would be across the board and that no particular operations will bear the brunt.

About 65% of the $3.5 billion budget will be spent on oil and gas exploration and production—about the same proportion as before the budget revision.

Chevron also will cut spending for refining and marketing, oil and natural gas pipelines, minerals, chemicals, and shipping operations.

Why cut back on capital outlays for minerals, say, or chemicals? Low oil prices are generally good news, not bad, for chemical manufacturing, because oil distillates are an important raw material.

By the way, most of the oil companies in Lamont’s sample were large, blue-chip companies. They could have raised additional capital from investors to maintain spending in their non-oil divisions. They chose not to. We do not understand why.

All large companies must allocate capital among divisions or lines of business. Therefore, they all have internal capital markets and must worry about mistakes and misallocations. But the danger probably increases as the company moves from a focus on one, or a few related industries, to unrelated conglomerate diversification. Look again at Table 32.3: How could top management of ITT keep accurate track of investment opportunities in 38 different industries?

Conglomerates face further problems. Their divisions’ market values can’t be observed independently, and it is difficult to set incentives for divisional managers. This is particularly serious when managers are asked to commit to risky ventures. For example, how would a biotech start-up fare as a division of a traditional conglomerate? Would the conglomerate be as patient and risk-tolerant as investors in the stock market? How are the scientists and clinicians doing the biotech R&D rewarded if they succeed? We don’t mean to say that high-tech innovation and risk-taking are impossible in public conglomerates, but the difficulties are evident.

The third argument for traditional conglomerates came from the idea that good managers were fungible; in other words, it was argued that modern management would work as well in the manufacture of auto parts as in running a hotel chain. Thus conglomerates were supposed to add value by removing old-fashioned managers and replacing them with ones trained in the new management science.

There was some truth in this claim. The best of the conglomerates did add value by targeting companies that needed fixing—companies with slack management, surplus assets, or excess cash that was not being invested in positive-NPV projects. These conglomerates targeted the same types of companies that LBO and private-equity funds would target later. The difference is that conglomerates would buy companies, try to improve them, and then manage them for the long run. The long-run management was the most difficult part of the game. Conglomerates would buy, fix, and hold. Private equity buys, fixes, and sells. By selling (cashing out), private equity avoids the problems of managing the conglomerate firm and running internal capital markets.[4] You could say that private-equity partnerships are temporary conglomerates.

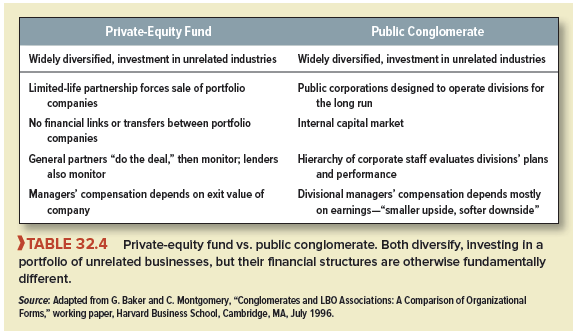

Table 32.4 summarizes a comparison by Baker and Montgomery of the financial structure of a private-equity fund and of a typical public conglomerate. Both are diversified, but the fund’s limited partners do not have to worry that free cash flow will be plowed back into unprofitable investments. The fund has no internal capital market. Monitoring and compensation of management also differ. In the fund, each company is run as a separate business. The managers report directly to the owners, the fund’s partners. Each company’s managers own shares or stock options in that company, not in the fund. Their compensation depends on their firm’s market value in a trade sale or IPO.

In a public conglomerate, these businesses would be divisions, not freestanding companies. Ownership of the conglomerate would be dispersed, not concentrated. The divisions would not be valued separately by investors in the stock market, but by the conglomerate’s corporate staff, the very people who run the internal capital market. Managers’ compensation wouldn’t depend on divisions’ market values because no shares in the divisions would be traded and the conglomerate would not be committed to selling the divisions or spinning them off.

You can see the arguments for focus and against corporate diversification. But we must be careful not to push the arguments too far. For example, in Chapter 33, we will find that conglomerates, though rare in the United States, are common, and apparently successful, in many parts of the world. They include such giants as Siemens in Germany, Philips in the Netherlands, Sumitomo in Japan, and Samsung in Korea.

Hello very cool web site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds also?KI’m happy to find a lot of useful information right here in the submit, we need develop extra techniques on this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .