When the labor market is competitive, all who wish to work will find jobs for wages equal to their marginal products. Yet most countries have substantial unemployment even though many people are aggressively seeking work. Many of the unemployed would presumably work for an even lower wage rate than that being received by employed people. Why don’t we see firms cutting wage rates, increasing employment levels, and thereby increasing profit? Can our models of competitive equilibrium explain persistent unemployment?

In this section, we show how the efficiency wage theory can explain the presence of unemployment and wage discrimination. We have thus far determined labor productivity according to workers’ abilities and firms’ investment in capital. Efficiency wage models recognize that labor productivity also depends on the wage rate. There are various explanations for this relationship. Economists have suggested that the productivity of workers in developing countries depends on the wage rate for nutritional reasons: Better-paid workers can afford to buy more and better food and are therefore healthier and can work more productively.

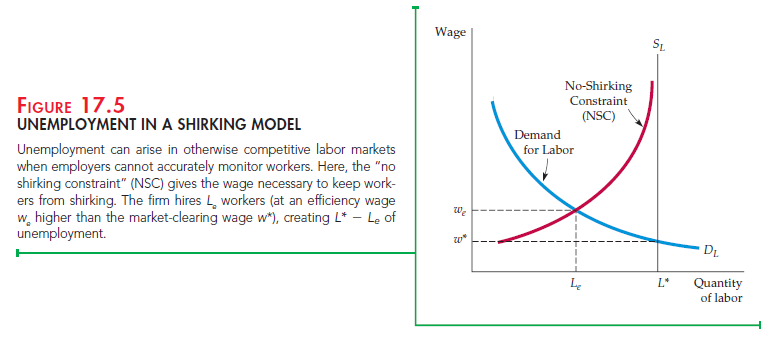

A better explanation for the United States is found in the shirking model. Because monitoring workers is costly or impossible, firms have imperfect information about worker productivity, and there is a principal-agent problem. In its simplest form, the shirking model assumes perfectly competitive markets in which all workers are equally productive and earn the same wage. Once hired, workers can either work productively or slack off (shirk). But because information about their performance is limited, workers may not get fired for shirking.

The model works as follows. If a firm pays its workers the market-clearing wage w*, they have an incentive to shirk. Even if they get caught and are fired (and they might not be), they can immediately get hired somewhere else for the same wage. Because the threat of being fired does not impose a cost on workers, they have no incentive to be productive. As an incentive not to shirk, a firm must offer workers a higher wage. At this higher wage, workers who are fired for shirking will face a decrease in wages when hired by another firm at w*. If the difference in wages is large enough, workers will be induced to be productive, and the employer will not have a problem with shirking. The wage at which no shirking occurs is the efficiency wage.

Up to this point, we have looked at only one firm. But all firms face the problem of shirking. All firms, therefore, will offer wages greater than the marketclearing wage w*—say, we (efficiency wage). Does this remove the incentive for workers not to shirk because they will be hired at the higher wage by other firms if they get fired? No. Because all firms are offering wages greater than w*, the demand for labor is less than the market-clearing quantity, and there is unemployment. Consequently, workers fired for shirking will face spells of unemployment before earning we at another firm.

Figure 17.5 shows shirking in the labor market. The demand for labor DL is downward-sloping for the traditional reasons. If there were no shirking, the intersection of DL with the supply of labor (SL) would set the market wage at w*, and full employment would result (L*). With shirking, however, individual firms are unwilling to pay w*. Rather, for every level of unemployment in the labor market, firms must pay some wage greater than w* to induce workers to be productive. This wage is shown as the no-shirking constraint (NSC) curve. This curve shows the minimum wage, for each level of unemployment, that workers must earn in order not to shirk. Note that the greater the level of unemployment, the smaller the difference between the efficiency wage and w*. Why is this so? Because with high levels of unemployment, people who shirk risk long periods of unemployment and therefore don’t need much inducement to be productive.

In Figure 17.5, the equilibrium wage will be at the intersection of the NSC curve and DL curves, with Le workers earning we. This equilibrium occurs because the NSC curve gives the lowest wage that firms can pay and still discourage shirking. Firms need not pay more than this wage to get the number of workers they need, and they will not pay less because a lower wage will encourage shirking. Note that the NSC curve never crosses the labor supply curve. This means that there will always be some unemployment in equilibrium.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my

newest twitter updates. I’ve been looking for a plug-in like

this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like this.

Please let me know if you run into anything.

I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

I really liked your post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

I was suggested this web site by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my problem. You are amazing! Thanks!